From Crookston to Cooperstown: Chet Brewer and John Donaldson Battle in a 12-Inning Integrated Duel

This article was written by Peter Gorton - Bill Staples Jr.

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Land of 10,000 Lakes (2024)

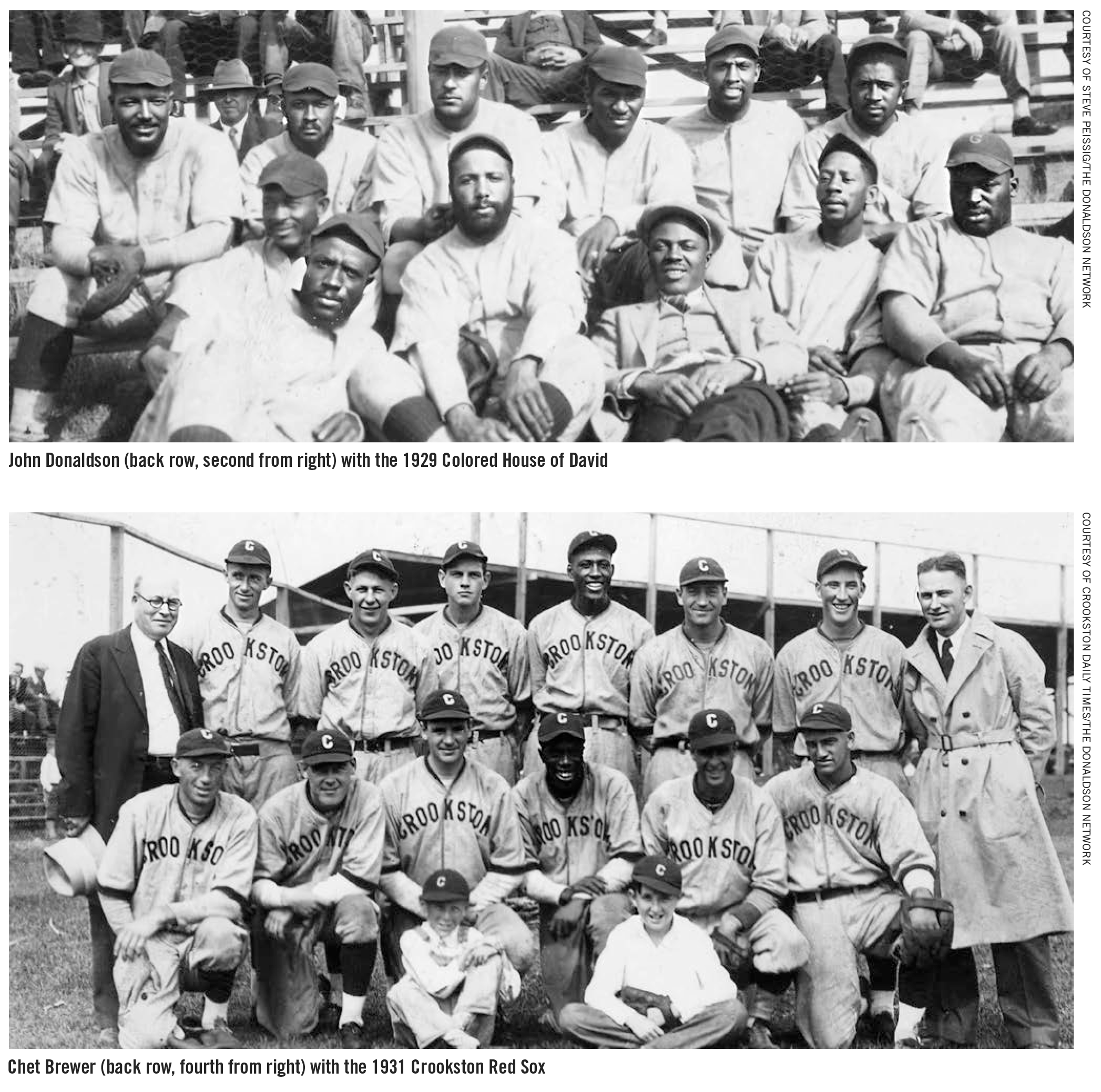

The 1931 baseball season began as the teeth of the Great Depression sank into economies around the world. Barnstorming baseball clubs hustled to entertain for the scraps of disposable income held by the agrarian public. When the northwestern Minnesota city of Crookston staged a pair of ballgames the weekend of Decoration Day, on May 30 and 31, baseball fans in the region buzzed with excitement.1 The Colored House of David, an all-Black barnstorming nine managed by the incomparable John Donaldson, would square off against the hometown Red Sox at Highland Field in east Crookston.

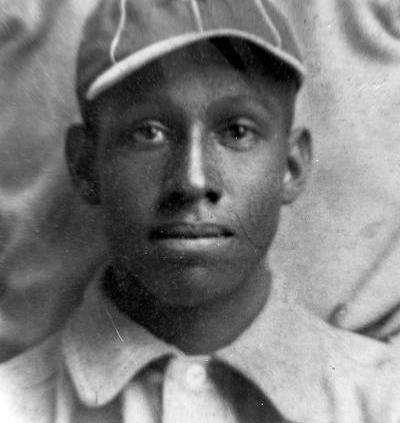

As early as 1911, Donaldson had begun hearing things like, “If he had a coat of whitewash [he] would be playing big-league ball.”2 This type of segregationist talk followed him in multiple forms through the years, leaving him to endure a career that would lead him everywhere except the white major leagues. Instead, he would become a “Negro” star in over 130 cities in Minnesota alone and was ranked as one of the top three pitchers of all time by the Pittsburgh Courier.3 So, by 1931, the start of his third decade of success in the Gopher State, his name meant riches to organizations bold enough to associate him with their entirely Caucasian towns. Donaldson’s opponents that weekend, the Crookston Red Sox, were not your typical town team. The club was managed by Walter “Dutch” Kiesling, Donaldson’s former teammate, who was a star in his own right. The 6-foot-3, 260-pound Kiesling was an imposing figure who was in the middle of a 13-year Hall of Fame career in the NFL as an offensive lineman with the Duluth Eskimos, Pottsville Maroons, Chicago Cardinals, Chicago Bears, Green Bay Packers, and Pittsburgh Pirates.4 He was playing first base for the long end of the gate receipts for the well-promoted clashes.

Kiesling’s team included two Black players, pitcher Chet Brewer and well-traveled catcher Jon Van, recommended by Donaldson and imported to balance the scales against his Colored House of David nine. Brewer was an electric 24-year-old right-hander who had proved his abilities were a level above while playing the previous six seasons with the Kansas City Monarchs. The Monarchs were an inaugural franchise in the Negro National League (NNL), and Brewer paid his dues and learned the game from some of the greatest pitchers ever: Jose Mendez, William Bell, Bullet Rogan and Andy Cooper.5

The economics of the day created uncertainty for every team, even more so than usual, and the heavily fortified Monarchs were no exception. They went independent after the 1930 season, as the NNL spiraled into dissolution.6 The instability of the times meant that outside clubs like Crookston could poach star players like Brewer.

The former Monarch followed a long line of great Black players to compete in Minnesota. Established stars like Dave Brown, Webster McDonald, and Donaldson proved for years that teams could make money with a Black man on the mound and the winner’s share of gate receipts. These exceptional players sought paydays not afforded to average Black players, and pitchers like McDonald, Donaldson, and Brewer inflated their bankrolls with good old-fashioned star power. Black stars could command premium shares of the gate, and fans were eager to shell out their hard-earned cash to watch them perform.

In the series opener on Saturday, the House of David defeated Crookston, 4–2, behind the pitching of 25-year-old Jimmy Truesdale and the fine glovework and bat of center fielder Gabby Street.7 On Sunday, Brewer and Donaldson took center stage, captivating fans with their command on the mound, while the formidable lineups of both teams battled toe-to-toe in an exhilarating showdown.

Donaldson and Kiesling submitted their lineups for their respective clubs to home plate umpire Ray Oppegaard.8 The cards read:

- Colored House of David – Charlie Hilton, 2b; Clarence Everett, ss; Gabby Street, cf; Nick Jones, rf; Charley Hancock, 1b; Manville “Fox” Boldridge, 3b; John Donaldson, p; Louis Williams, c; Pascoe “Scrapper” Wright, lf.

- Crookston Red Sox – Stanley Berquam, cf; George Lee, 2b; Joe Bach, ss; Walt Kiesling, 1b; Jon Van, c; Freemont Phillips, 3b; Joseph Teie, rf; Ernest Teie, lf; Chet Brewer, p.

From the outset, it was evident that both club’s aces were in top form, each delivering a stellar performance that kept opposing batters at bay. Brewer showcased his finesse by allowing a mere five hits throughout the game, a testament to his pinpoint accuracy and unwavering focus. Armed with a wicked overhand curveball that appeared to drop just before reaching the hitter’s bat, Brewer notched five strikeouts and forced 23 groundball outs.9

Meanwhile, the 40-year-old Donaldson faced a relentless offensive barrage from the Red Sox, surrendering nine hits. One of Donaldson’s greatest strengths was his ability to pitch to the right part of the lineup. His control of the game—and control in the strike zone—was an element people came to watch. He managed the game from the mound, often walking batters intentionally to find a weak link in the lineup. His ability to command the game was reflected in the box score, with a balanced attack of 13 strikeouts and 13 groundouts.

The game unfolded with a series of tense moments and thrilling exchanges. Despite numerous scoring opportunities, neither side could capitalize, leaving runners stranded on base and heightening the drama on the field. Both pitchers were in control.

In the top of the seventh inning, momentum shifted in favor of the Colored House of David when Jones unleashed a double, setting the stage for Hancock’s RBI single that propelled his team into the lead. However, Brewer’s exceptional defensive play and strategic pitching prevented further damage as he deftly navigated through the Colored House of David lineup with poise and precision.

On the opposing side, the Red Sox rallied behind Brewer, mounting an effort to level the score. In a pivotal moment in the bottom of the seventh inning, Brewer himself delivered a home run that electrified the crowd and reignited his team’s hopes of victory. Despite initial controversy over whether the hit was a two-base or four-base wallop, the umpires confirmed Brewer’s homer, igniting a surge of excitement among Red Sox fans.

As the game moved into extra innings, tension reached a fever pitch as both teams fought tooth and nail for the win. In the 10th inning, the Red Sox almost secured the victory. Kiesling led off with a single past first. Van lifted a high fly to right field. Phillips, who had gone hitless for the afternoon, slugged a double to deep center. Kiesling started at the crack of the bat but was thrown out at the plate after a perfect 8–4–2 relay, Street in center field to Hilton at second to catcher “Pud” Williams, who fearlessly held his ground knowing that the stout Kiesling was barreling home.

Despite the best efforts of both teams, in the end, the game was called per Sunday baseball regulations limiting play after 6PM.10 At the end of the 12th inning, and after 2 hours and 40 minutes of the most exciting pitching duel ever witnessed in Crookston, players and fans alike were left with a sense of anticipation for the next matchup between Brewer and Donaldson. The box score from the Crookston Daily Times on June 1, 1931:

NO REMATCH IN THE MAJORS

Donaldson was known as “The Master of the Situation” on baseball fields across the continent for his proficiency playing in the segregated game.11 When the situation in baseball and society intersected—notably the exclusion of Black players—fans could see what was happening right before their eyes. “The situation,” was obvious to anyone: These players were excluded for one reason, their lack of whiteness.

This glaring omission was beginning to wear at the color line. Newspapers stated the obvious when they said things like: “Many colored fans are beginning to resent this situation.”12 Donaldson and Brewer knew this “situation” intimately.

To succeed in segregated baseball, players adapted their behavior to fit into Jim Crow America and survive. Sometimes Donaldson was the only Black player on the diamond. His daily life was wrought with discrimination and misinformation portraying Blacks as inferior. One newspaper in Minnesota even went so far as to write, “A colored man must be careful in taking liberties when alone among whites.”13 There was little doubt about exactly where white power within society wanted men like Brewer and Donaldson.

Donaldson did get overtures. New York Giants manager John McGraw had attempted to pass Donaldson as Cuban a decade and a half before.14 He was certainly good enough to break the color line in the 1910s, but too famous to pass as an acceptable shade of white. It was a backhanded compliment, and even if his reputation hadn’t prohibited the scheme, Donaldson wanted nothing to do with it.15 Another impossibility dangled to another Black man that whites could and would recant. The reality was a Black man could only do so much in white society. Donaldson and others who looked like him were continually offered what seemed like equality only to eventually see integration as a mirage.

The Colored House of David, led by Donaldson, and the Crookston Red Sox, led by Brewer, tangled that late May in Crookston, Minnesota. To play in Crookston, each spent considerable capital. It seems a shame today the game had no definitive outcome. It’s impossible not to think they both felt dissatisfied, but the lack of satisfaction was nothing new.

Later that season, the Kansas City Monarchs reorganized as a barnstorming unit. Brewer and Donaldson would eventually become teammates in 1931 and together they would navigate Jim Crow, their economic realities, and their baseball careers.16

COOPERSTOWN CALLING?

Thirty-seven people have been inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame for their careers in the Negro Leagues. (See Table 1.) Despite boasting career credentials for inclusion, neither Donaldson nor Brewer is one of them.

Both were among the 39 candidates on the ballot in 2006, yet each fell short of the required 75 percent of the votes for induction. They were not alone though, as stellar players like Dick “Cannonball” Redding and Walter “Dobie” Moore and the beloved ambassador Buck O’Neil also missed the cut.17

Of the candidates on that ballot, 17 were inducted, thanks in part to the composition of the special committee selected to evaluate their credentials. All 12 voting members held some level of expertise in Negro Leagues baseball history.18

Since then, more information about the careers of Donaldson and Brewer has surfaced, bolstering their Hall of Fame candidacies. Unfortunately, the Negro Leagues history landscape and the expertise tapped to survey that landscape have changed.

In December 2020, Major League Baseball announced that it was officially designating the Negro Leagues as “major leagues.”19 This declaration was met with mixed responses, as the scope of the designation is both time- and geography-bound, limited to Black baseball played between 1920 and 1948, and only by teams that participated in select leagues. For players like Donaldson and Brewer, whose pitching talents and quest for economic justice resulted in constant travel, the scope and impact of their careers cannot be fully appreciated within these myopic parameters.

At the same time, the Hall of Fame modified its approach to recognizing and honoring Negro Leaguers through the creation of Era Committees.20 This change resulted in the longest gap in time (16 years) without a Negro Leaguer being enshrined in Cooperstown since Satchel Paige was the first in 1971. Between 2006 and 2022, not a single player or pioneer from the Negro Leagues was inducted.

What’s more, not all voters currently on these special Era Committees possess the same level of Negro Leagues expertise as those back in 2006. For example, of the 16 voters selected for the Early Baseball Era ballot of 2022, only three (Gary Ashwill, Adrian Burgos Jr., and Leslie Heaphy) are Negro Leagues historians. The rest are baseball history generalists or former players, like Bert Blyleven, Fergie Jenkins, Ozzie Smith, and Joe Torre.21 As a result, only two Negro Leaguers—O’Neil and Bud Fowler, a candidate not on the 2006 ballot—received 75 percent of the votes.22

The Early Baseball Era has been rebranded as the Classic Baseball Era for the upcoming election in December 2024.23 But given that the composition of the voting committee members remains unchanged, optimism for Donaldson and Brewer to achieve enshrinement is low.

With the current approach of relying on uninformed, non-Negro Leagues historians to cast votes for Negro Leagues candidates, the odds are likely that the results of any future election involving Donaldson and Brewer will resemble the 12-inning battle that occurred on that Sunday in May 1931 in Crookston— where, despite the excellence exhibited on the mound, the perverse conditions in which the game was played resulted in an outcome that left neither man a winner. Thus, their battle for respect continues.

PETE GORTON, a SABR member for 19 years, is a founder of The Donaldson Network (johndonaldson.bravehost.com).

BILL STAPLES JR., of Chandler, Arizona, has a passion for researching and telling the untold stories of the “international pastime.” A SABR member since 2006, his areas of expertise include Japanese American and Negro Leagues baseball history as a context for exploring the themes of civil rights, cross-cultural relations, and globalization. He is a board member of the Nisei Baseball Research Project and Japanese American Citizens League–Arizona Chapter, and chairman of the SABR Asian Baseball Committee. Learn more at zenimura.com.

Notes

1 Decoration Day is now recognized and celebrated as Memorial Day. Learn more at: “The History of Memorial Day,” PBS, undated, 2023, https://www.pbs.org/national-memorial-day-concert/memorial-day/history/.

2 “Coons Were A Hoodoo,” Ackley (Iowa) Inter-County Journal, August 18, 1911, 1.

3 John Donaldson is known to have played in 766 different cities in North America and 132 in Minnesota, according to The Donaldson Network, https://johndonaldson.bravehost.com/. Ranking found in “Dismukes Selects Nine Best Pitchers in Diamond History,” New Pittsburgh Courier, February 15, 1930, 14: https://www.newspapers.com/article/new-pittsburgh-courier-dizzy-dismukes-se/147787480/.

4 “Walt Kiesling, Class of 1966,” Pro Football Hall of Fame, undated, https://www.profootballhof.com/players/walt-kiesling/.

5 Thomas Kern and Bill Staples Jr., “Chet Brewer,” SABR, undated, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/chet-brewer/.

6 “1931 Season, Independent Clubs,” Seamheads Negro Leagues Database, undated, https://www.seamheads.com/NegroLgs/year.php?yearID=1931&lgID=IND.

7 “Colored Boys Down Locals 4-2 Saturday,” Crookston (Minnesota) Daily Times, June 1, 1931.

8 “Game Called in 12th with Count 1-All,” Crookston Daily Times, June 1, 1931.

9 “Brewer recalls wild ride with Satchel Paige,” Des Moines Register, April 1, 1984, 30.

10 “Game Called in 12th with Count 1-All,” Crookston Daily Times, June 1, 1931.

11 “Donaldson in Perfect Condition to Meet Rivals from Up-River City,” St. Cloud (Minnesota) Times, July 19, 1930, 12, https://www.newspapers.com/article/st-cloud-times-john-donaldson-master-of/141716603/.

12 Hamlet B. Rowe, “Sport World,” Minneapolis Timely Digest, July 1, 1931, 22.

13 “Clarkfield Baseball Team Wins Championship Game,” Clarkfield (Minnesota) Advocate, August 5, 1926, 1.

14 “Donaldson to Hurl in Game with Bats,” Globe-Gazette (Mason City, Iowa), June 28, 1932, 9.

15 Brian Flaspohler, “John Donaldson,” SABR, undated https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/john-donaldson-2/.

16 “Monarch Hurler Defeats Cubans,” Omaha World Herald, September 28, 1931, 9.

17 Bill Francis, “Negro Leagues Committee members reflect on the historic 2006 election,” National Baseball Hall of Fame, undated, https://baseballhall.org/discover/negro-leagues-committee-members-reflect-on-2006-election.

18 Carter Gaddis, “One Shining Moment,” Tampa Tribune, February 26, 2006, Sports 1.

19 “MLB officially designates the Negro Leagues as ‘Major League,’” MLB.com, December 16, 2020, https://www.mlb.com/press-release/press-release-mlb-officially-designates-the-negro-leagues-as-major-league

20 “Hall of Fame makes series of announcements,” National Baseball Hall of Fame, July 23, 2016, https://baseballhall.org/discover-more/news/hall-of-fame-announcements.

21 “Golden Days Era Committee, Early Baseball Era Committee ballots to be considered Dec. 5,” National Baseball Hall of Fame, November 29, 2021, https://baseballhall.org/news/golden-days-era-committee-early-baseball-era-committee-ballots-to-be-considered-dec-5.

22 “Baseball legend Buck O’Neil voted into the Hall of Fame,” Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, December 14, 2021, https://www.nlbm.com/kansas-city-baseball-legend-buck-oneil-finally-inducted-into-the-hall-of-fame/.

23 “Era Committees,” National Baseball Hall of Fame, https://baseballhall.org/hall-of-fame/election-rules/era-committees.