Satchel’s Wild Ride: How Satchel Paige Finally Made the Hall of Fame

This article was written by Mark Armour

This article was published in Fall 2024 Baseball Research Journal

Editor’s note: This article was selected as a recipient of the 2025 McFarland-SABR Baseball Research Award.

On July 25, 1966, Casey Stengel and Ted Williams were inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. Although most observers likely assumed that Casey would steal the show, as he usually did, it was Williams who provided the audience with the indelible memory. He spoke fewer than 500 words, taking just three minutes, thanking people from his childhood all through his wonderful career. And in the middle of his speech, he said this:

The other day Willie Mays hit his 522nd home run. He has gone past me, and he’s pushing, and I say to him, ‘go get ‘em Willie.’ Baseball gives every American boy a chance to excel, not just to be as good as someone else, but to be better than someone else. This is the nature of man and the name of the game, and I’ve always been a very lucky guy to have worn a baseball uniform, to have struck out or hit a tape-measure home run. And I hope that someday the names of Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson in some way can be added as a symbol, to the great Negro players that are not here, only because they were not given a chance.1

These are some of the most famous words Williams ever spoke, and among the most impactful and memorable ever spoken at any of the dozens of Hall of Fame inductions. And, make no mistake, this was an extraordinary gesture.

“These were brave, eloquent words, spoken by a man who was in a position to know,” wrote Charles Livingston days later in the Louisville Defender. “A lesser man than Williams, preoccupied with his own hour of glory, would have completely forgotten or ignored other contemporary greats, particularly those of the Negro race. Ted, however, is no small man when it comes to accessing the worth of others.”2

Although I have found no evidence that Williams ever met Gibson, Ted and Satchel were quite friendly. Williams often told the story of seeing Paige pitch in San Diego when Ted was a boy, likely in the early 1930s. (When Paige finally was allowed to pitch in the American League, when he was in his 40s and Williams was the best hitter in the world, Ted managed just two singles in nine at bats against him.3) In 1956, when Paige was pitching for Triple-A Miami in the International League, writer Jimmy Burns ran into Williams at the All-Star Game in Washington. As Burns was walking away, Ted stopped him. “Be sure and give Satchel Paige my best regards when you get back to Miami.”4 Williams’ words in Cooperstown should not have been a total surprise because he had made related comments to The Sporting News in January when he was first elected. “I feel there should be no hard and fast rules that can’t be bent once in a while,” he said. “There’s one man who should be in and that’s Satchel Paige.”5

Still, Ted’s generous remarks have made me wonder about whether any others might have held similar views in 1966, how his remarks were received at the time, and why, if Williams’s words were so compelling and effective, did it take five more years for Paige to have his own moment on that grand baseball stage?

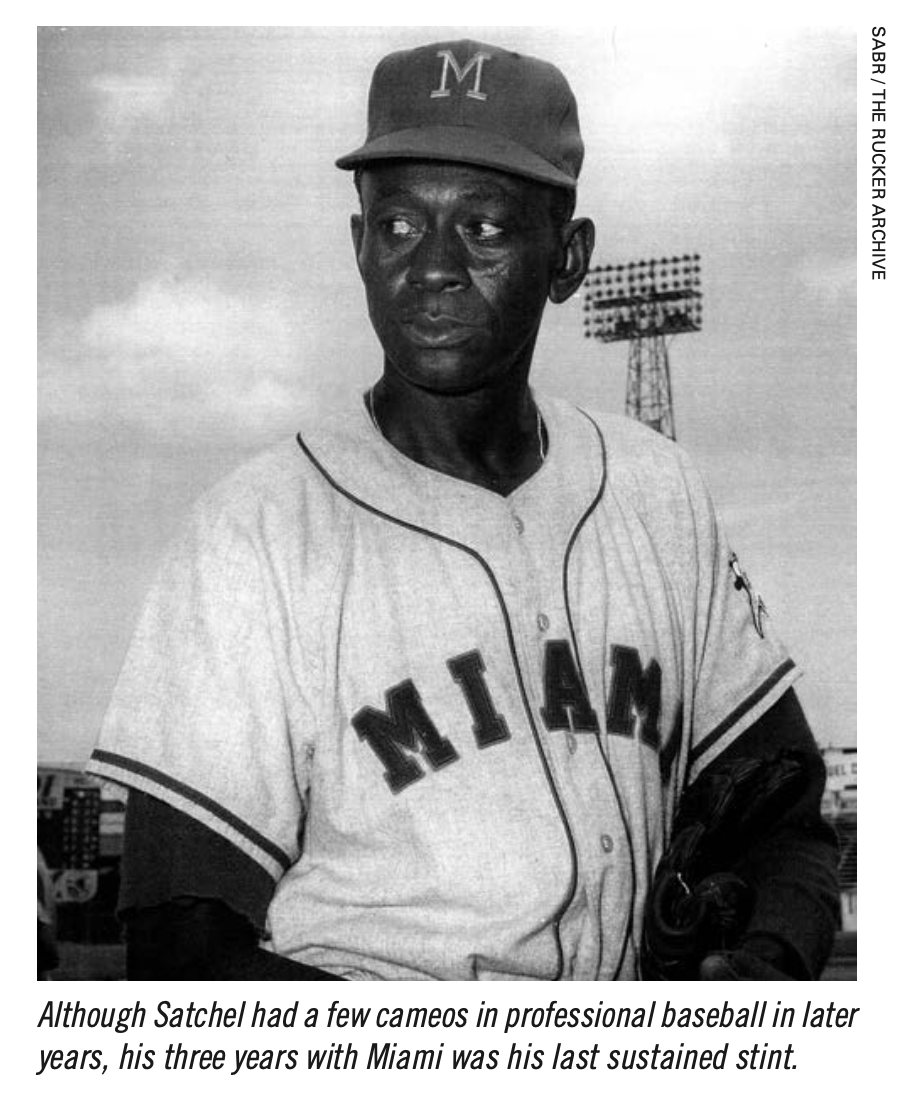

I focus on Paige, rather than some of his illustrious Black contemporaries, because most of the discussion at the time focused on him. He was by far the best-known Black player in white America during his Negro League career. But he was also the most prominent such player who went on to play in integrated leagues. In the 1950s, great players like Gibson, Oscar Charleston, Rube Foster, and Buck Leonard were either retired or deceased, while Paige was making All-Star teams for the Browns and winning 31 games in three years for Miami. More than one commentator would come away from a Paige outing and wonder, “Imagine how good he must have been.”6 Satchel Paige was the introductory course in white baseball fans’ appreciation of the Negro Leagues, while remaining a walking advertisement to their greatness.

Prior to Williams’ speech, at least one other prominent player had touted Paige for the Hall of Fame: Bob Feller, who did so in the runup to his own election to the Hall in 1962. In a first-person account for the Saturday Evening Post that January, Feller said: “I believe very strongly that there should be a niche for Satchel Paige. To be sure, his major league record doesn’t qualify him, but that was only because the old color line kept him out of the majors for so many years.”

“I barnstormed with Satch annually,” Feller continued, “starting back in ’37, when both of us could really hum that ball. Satch had a team of relatively untrained Negro players. My men bore down to see what they could do against the fabled Satch Paige. They couldn’t do much. By the time he came to the major leagues, Paige was getting by mostly on savvy. Still, nobody stopped Joe DiMaggio as cold as he did.”7 (To Feller’s point, DiMaggio hit .342 with 11 home runs off Feller, while he was 0-for-8 against Paige with three strikeouts.)

But Ted Williams’s public support of Paige predated Feller’s. He had lobbied for Paige way back in 1953. Williams was a captain in the US Marine Corps. While stationed at a base in El Toro, California, awaiting transport to Korea, he gave a far-ranging interview to the Army Times. Williams praised Paige as a brilliant pitcher, and expressed the hope that there could be a niche in the Hall of Fame for him.8

It is important to remember that at that time the Hall of Fame had been around barely 15 years, and Williams was not really concerned with (or maybe even aware of) the Hall’s rules and procedures. Paige was still an active pitcher, but so what? The way Williams saw it, Paige had been a great player for many years and what else really mattered?

Baseball writers were the principal voices in both shaping and reflecting public opinion on baseball segregation. To that end, there were voices in the Black press who had lamented from the Hall’s earliest days that their heroes were being left out. In January 1939, in a column outlining his hopes for the upcoming year, Art Carter in the Baltimore African-American included this wish: “Newspapermen forget prejudice and vote Rube Foster a niche in baseball’s Hall of Fame.”9

The Norfolk Journal and Guide wrote as early as 1942 that “Satchel Paige will hardly be among those granted a place in baseball’s coveted hall of fame, but both his ability and sportsmanship will find a place.”10 In 1947, upon the death of Josh Gibson, the Kansas City Call wrote: “He earned the right to a place in baseball’s Hall of Fame. His color alone can keep him out.”11 All three of these men—Foster, Paige, Gibson— were frequently cited as players who “would have” had Hall of Fame careers had they been allowed.

A shift in the dialogue took place about 1950, when serious writers began suggesting that these men did have Hall of Fame careers. The first such argument that I have seen was put forth by Joe Williams of the New York World Telegram and Sun in February 1950, when Paige had just been released by the Indians, seemingly ending his major-league career.

Come to think of it, why should old Satch be kept from the Hall simply because it takes so long to right an ancient social wrong? From now on he becomes … an automatic write-in on my ballot. In this way baseball, through the press box, can help make amends for the artistic recognition and fiscal rewards denied him down through the years when he was as good as any pitcher in the country. Possibly better.12

True to his word, Williams remained a tireless Paige advocate for the next 20 years.

Many in the Black press took up the cause, often making the case for Negro League stars generally, not just Paige. Joe Bostic wrote on this issue as early as 1951 in the New York Amsterdam News. “It’s high time that Sir James Crow be voted out of membership on the voting board for the Hall of Fame,” he wrote. “Either that or continue the glorification of the mediocre.”13 Like Joe Williams, Bostic beat this drum for years.14 Other vocal allies included Marty Richardson in the Cleveland Call,15 Russ Cowans in the Chicago Defender,16 and John Johnson in the Kansas City Call (“If there is no place there for him, then none are worthy”17).

White writers, who were more likely to be voters, also began writing articles advocating for Paige. Gordon Cobbledick of the Cleveland Plain-Dealer was making the case by 1952.18 The editor of the Detroit Times sounded the call soon after.19 Gayle Talbot of the Associated Press, read all over the country, weighed in for Paige in August that year.20 Harold Kaese in the Boston Globe, Dave Condon in the Chicago Sun-Times—syndicated writers with reaches that extended far beyond their local metro areas— wrote about Paige and the Hall often.

In November 1952, the National Sports Editors reported the results of a poll of their members on the question: “Should Satchel Paige Make the Baseball Hall of Fame?”21 The results (I have not found precise vote totals):

- 69% Should

- 13% Should Not

- 9% Undecided

- 9% No Opinion

Then and now a player needed 75% on the writer’s ballot to be inducted, so these results strongly suggest that Paige would have had a good shot at election as early as 1952, had he been eligible.

Was the Paige “campaign” touted or covered less in the white Southern papers? Undoubtedly, since the most prominent advocates were from the north—the Southern papers printed the columns that they chose to syndicate. But, while one can’t read every newspaper, I did find examples of pro-Paige arguments in Southern newspapers. For example, in August 1952 the Hattiesburg American ran an AP story from Talbot that began, “A movement is afoot to vote Satchel Paige, the practically ageless Negro pitcher, into baseball’s Hall of Fame, and after considerable thought we have decided it is the thing to do.” The story closed: “… Who can doubt what the man would have done 20–25 years ago if he had had the opportunity.”22

The poll cited above was touted in several Southern newspapers, including the Foley Onlooker, the Pascagoula Chronicle, and the Green County Democrat (Eutaw, AL). The Huntsville Times published Joe Williams regularly, including several columns on Paige. In early 1954, the Monroe Journal, from Monroeville, Alabama, published an editorial touting Paige for the Hall of Fame: “He has been a towering figure in the mythology of the game for a couple of decades, and he should not be left out of the Hall of Fame simply because the color of skin kept him out of the Majors.”23

Ed Fitzgerald was the longtime editor of SPORT, a highly respected national magazine unafraid to weigh in on racial matters. In the November 1952 issue, Fitzgerald wrote a three-page editorial asking his readers to contact their local baseball writer and urge a vote for Paige immediately. “There is no rule,” wrote Fitzgerald, “which would bar Satchel from membership because of his race or because of the relatively few seasons he has played in organized ball.”24

This last part might be a surprise. As of 1952, the only instructions on the writers’ ballot were that the player had to have played in the past 25 years, and that he had to be retired for at least one season.25 Paige would be eligible one year after he finally hung up his uniform. Many observers wanted the Hall of Fame to ignore even that requirement—the Hall was still very young, and certainly capable of modifying or waving the rules as it saw fit. “This is an exceptional case and should be treated as one,” wrote L.B. Davis in the Wichita Post-Observer. But Paige’s primary advocates, like Joe Williams, would often write that Paige’s largest obstacle might be that he was never going to stop pitching.27

In July 1953 the Hall of Fame board of directors enacted several procedural changes, including the creation of another version of what has come to be called the Veteran’s Committee. The latest VC was a group in charge of electing players, managers, and umpires who had finished their careers more than 25 years ago. More important to our story, the board also changed the eligibility for the writers’ ballot to require that a player be retired for five years, rather than just one.28

After the 1953 season Bill Veeck sold the Browns to a group who moved the team to Baltimore. One of the new owners’ first acts was to release Satchel Paige from his contract. Paige spent the next several years pitching and hoping for another shot at the big leagues. The closest he came was the three years he pitched, very well, for the Triple-A Miami Marlins, where observers continually made the case that he could help a big-league team. But as things stood in 1954, Satchel would become eligible for the Hall of Fame in 1959.

This remained the situation until July 1956, when the Hall board made additional rules changes, importantly one that required that any candidate have played parts of at least ten major league seasons.29 Unless he somehow signed up with a major league team and tacked on five more seasons of pitching, Paige’s candidacy was over barring special consideration. The ten-year rule applied to both the writers’ ballot and the Veterans group that was considering older players.

This changed the story considerably. Before the two rules changes (often called the “five-year rule” and the “ten-year rule”), the writers were in charge. All the columns urging that Paige be elected had been aimed at the BBWAA: “once he is eligible, please vote for Satchel.” The decision was no longer in the writer’s hands, it was in the hands of the Hall’s Board of Directors. Instead of “please vote for Satchel,” the message had become “please change the rules.”

So, who was the Board of Directors?

The Hall of Fame was and is run by people associated with or appointed by the Clark Foundation. Although the board of directors today is mainly made up of people from the baseball world, that was not always so. In 1958, for example, there were ten members of the board. Three were from major league baseball: the commissioner (Ford Frick), and the two league presidents (Warren Giles and Will Harridge). The other seven were Foundation people, many of them Cooperstown residents. The president was still Stephen C. Clark, who had founded the Hall of Fame in 1936. The vice president was Paul Kerr, who helped run the Hall for nearly 40 years, including 18 as president. Other directors included Stephen Clark Jr., James Bordley, Rowan Spraker, Howard C. Talbot, and Clyde S. Becker.30 Their names are less important than the point that the board was composed of mainly businessmen. To get Satchel Paige and other Negro Leaguers into the Hall of Fame, these are the men who needed to be convinced.

Ironically, Paige picked up perhaps his biggest endorsement just a few weeks after the 10-year-rule change. The Sporting News, the so-called “Bible of Baseball,” which had expressed skepticism about the talents of Black players as integration was unfolding, published a full-throated editorial in support of Paige’s election. “On the wall of the pantheon honoring the greatest players,” they wrote, “there should be room for the likeness and records of Leroy (Satchel) Paige.” The editorial was unsigned, but it would have come with the approval (perhaps even the authorship) of J.G. Taylor Spink, the publisher who enjoyed a close relationship with the Hall of Fame as chairman of the Veteran’s Committee.31

Joe Williams also had no intention of letting up. After Paige got back in the news for throwing a 1-hit shutout for Miami in August 1956, the writer got back to work. “Isn’t there anyone at all among the game’s leaders who will agree that in view of the prejudice which condemned him to a generation of skid-row baseball, that this incomparable artist is entitled to special consideration? To install Paige in the Hall by executive order—and without further delay—would constitute no more than a simple, belated recognition of a high talent. Atonement, there can never be.”32

Over the next several years, more writers joined the cause, urging someone, anyone, to right this wrong. “How would you like it if you were the world’s greatest tenor,” asked Jim Murray in 1964, “but had to stand outside the opera house with an organ grinder selling pencils, while a guy who couldn’t come within two octaves of you stood on stage receiving curtain calls and showers of money? … When you have imagined that, you are well into an understanding of ‘This is your life, Satchel Paige.’”33

Feller’s Saturday Evening Post column appeared in 1962, sparking new advocates: Jimmy Powers and Dick Young in the Daily News, Wells Twombly in the San Francisco Examiner, Stan Isaacs in Newsday. “Paige for the Hall” was not a fringe position; these were among the most popular and widely syndicated sports writers in the country. It appeared that a decided majority of baseball writers wanted Satchel to get a plaque.

The great Wendell Smith caught up with Paige in 1965 at a Harlem Globetrotters game; Satchel was touring with the team—speaking to the crowds at halftime and acting as a foil for some of their gags. In Smith’s glowing profile of the 58-year-old legend you can feel the author’s appreciation and joy, yes, but also frustration—after all these years, all Satch’s pitching, all Smith’s columns, his hero was still not adequately appreciated: “It is regrettable that such a human is not in the Hall of Fame.”34

That summer Paige was celebrated at Cleveland Stadium before an Indians-Yankees game to mark his induction into the Cleveland Indians Hall of Fame. There were 56,634 people in attendance, the largest Indians crowd in three years. Taking this as proof that he remained the people’s choice, the event stirred up more Satchel columns. Coincidence or not, Kansas City Athletics owner Charles Finley soon signed Paige to a major league contract. Paige pitched three innings in a game for Kansas City in September, facing ten batters. The 59-year-old gave up no runs and one hit, a double to Carl Yastrzemski.

The important question, by the time Ted Williams made his speech in July 1966, was this: Who was keeping Paige out? The short answer: the Hall of Fame board of directors. Specifically, there were two big obstacles. The first was Ford Frick, who was the commissioner of baseball through 1965, and a longtime member of the board even after he left his baseball post. Two years before Williams’s speech, Frick had said: “We can’t alter the rules for old Satchel. … If you make one exception, you have to make many.”35

The second, and more important, were the businessmen who ran the Hall of Fame. While the Hall’s board delegated the voting to the writers or a hand-picked committee, the board made and still makes the rules: Who votes? How often do they vote? Who is eligible this year, as opposed to next year? In 1953 and 1956, the board made changes to the eligibility rules that made it impossible for players who played most of their careers outside of the then-extant major leagues to make the Hall. The only mechanism available would have been some sort of special election, and the board had resisted such a step even in the face of years of pleading.

“Sure, Satchel has done a lot for the game,” Hall director Ken Smith said in 1964, “but he just doesn’t qualify for it on his major league record. We all love the guy, but it just wouldn’t be right to bend the rules.”36 The cruel irony that Paige had been denied the opportunity for twenty years and now was being punished for this denial was apparently lost on Smith and his fellow directors.

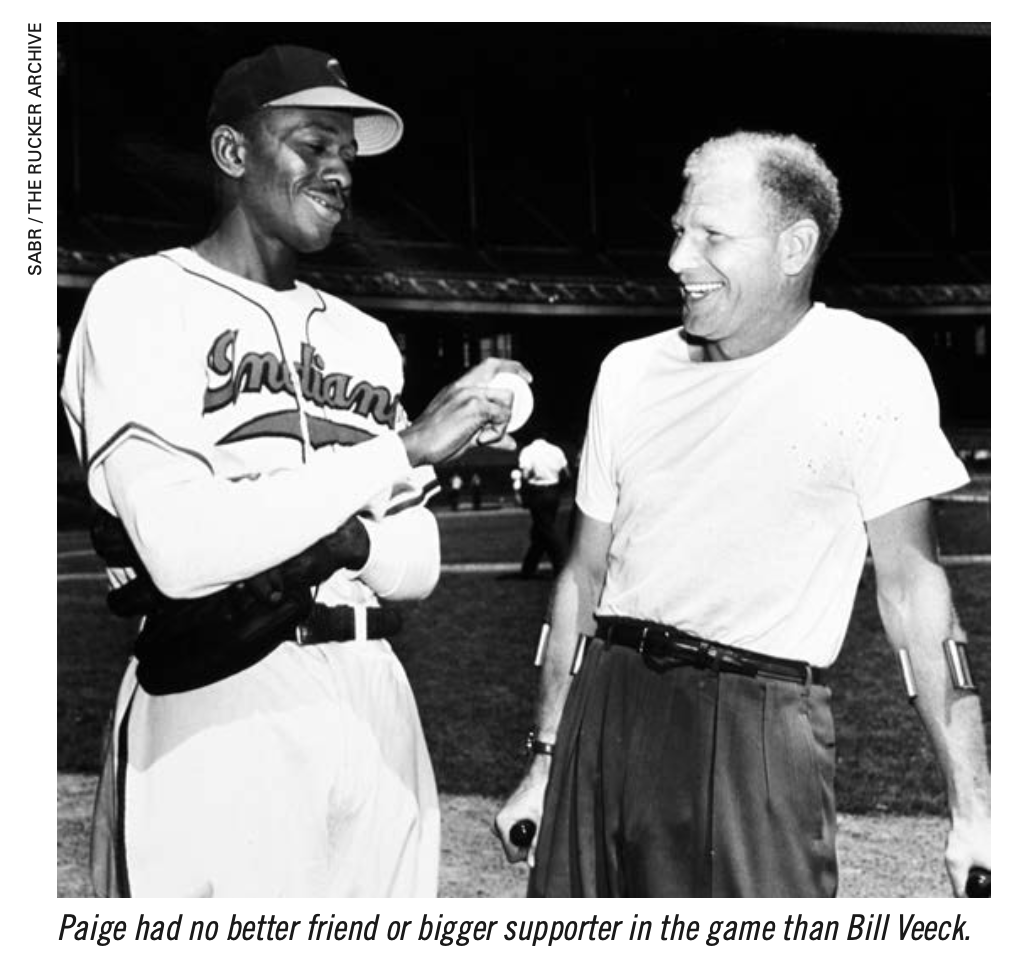

Within the world of baseball Paige had no greater friend than Bill Veeck. Veeck, as owner of the Cleveland Indians, signed Paige in 1948 when most thought he was too old, and was rewarded with a world championship the Indians almost certainly would not have otherwise won. Veeck signed Paige in 1951 when he owned the Browns, and signed him a third time in 1956 when he ran the Miami Marlins. On all three occasions Paige pitched very well for multiple seasons.

And Veeck advocated for Paige’s inclusion in the Hall of Fame often in interviews, speeches, and newspaper columns. “Why shouldn’t Paige be in the Hall of Fame?” Veeck asked in 1965. “Isn’t the Hall of Fame for all of baseball? Sometimes we forget that a lot of baseball is played in places other than the major leagues.”37

In August 1965, following a hip injury he had suffered in a fall, Casey Stengel retired as manager of the New York Mets.38 Although no great shakes with the Mets, his 10 pennants and 7 World Series titles with the Yankees made him an overwhelmingly deserving candidate for baseball’s Hall of Fame. Unfortunately, the 75-year-old Casey was ineligible for immediate election since the rules required that he wait five years. So that was that.

Except that was not that. On December 2, the BBWAA sent a note to Hall president Paul Kerr, as follows: “The Baseball Writers Association has voted unanimously to recommend to the Hall of Fame Committee that it act immediately—and favorably—on the candidacy of Casey Stengel as a member of the Hall of Fame.” Many executives throughout the game publicly endorsed the sentiments.39

On December 9, longtime big league executive Branch Rickey passed away. There was no provision at the time for bestowing Hall of Fame honors on executives—this was something the Hall had dealt with as needed, but the last general manager inducted had been Ed Barrow back in 1953, before the current Veterans Committee process had been put in place. “It is not within my power to grant a dispensation,” said Kerr. “We can’t do a thing without changing the rules. If we don’t follow protocol, we invite chaos.”40

“If Stengel and Rickey are to be selected,” continued Kerr, “it will have to be by the Veterans’ Committee, which will have to change the present rules. The board of directors of the Hall of Fame has the right to revoke, alter, or amend any changes, but this has always been a formality.”41 This last part was at best misleading, at least as it relates to Negro Leagues players. Indeed, the Board had changed the rules to make their election impossible.

So, on January 30, 1966, the Veterans Committee indeed changed their rules to (a) waive the five-year rule for anyone who retired after the age of 65, which took care of Stengel, and (b) added executives to the list of eligible candidates, which took care of Rickey. Easy-peasy. Stengel was elected on March 8, and Rickey a year later. The haste with which these eligibility problems were resolved for these two obviously deserving candidates, when contrasted with the stonewalls constructed for Paige, is remarkable.

At least a few writers made the connection, including A.S. “Doc” Young: “But now that the committee has proven that it is swayed by human, as well as artistic, considerations—a hip fracture forced the great Casey to quit managing—let us hope, let us pray, that it can do something about Satchel Paige.”

“For sheer artistry and sheer fun, not to mention his overlooked mental genius, no man was ever superior to Leroy (Satchel) Paige,” Young added. “The game has never known a more valuable goodwill ambassador.”42

That July, Stengel and Ted Williams had their big day in Cooperstown, and Williams made the speech that began our story. Doc Young lamented that he had not been present, as Williams was a man he had admired for many years. “I wish I had been there to glory in that moment,” he wrote. “To walk up to my boyhood batting hero and say, ‘you’re the greatest. You’ve got soul.’”43 Many other stalwarts in the Black press agreed, gushing over Williams for his courage and humanity. The Los Angeles Sentinel, for example, wrote: “If Satchel Paige never makes it into the Hall of Fame, a spot he richly deserves, it must make him glow inside to know that Ted Williams knows he belongs there.”44 The Michigan Chronicle wrote that “Of Williams’s many fine moments in baseball, this acceptance speech was perhaps his finest.”45 This might have read like hyperbole in 1966, but not so much today.

It is not obvious whether more writers got on board after Williams’s speech since so many were already there. If there was a shift in the debate it was in its tone, suggesting Williams might have emboldened some of them. While many of the pro-Paige voices, certainly including Ted’s, had previously been understated, many columnists became decidedly more aggressive. Whereas Joe Williams felt the need to recite some of Paige’s qualifications a decade earlier, the need for that seemed to have passed. No one was debating whether Paige was an all-time great pitcher any longer. “He is a walking reproof to the game whenever he turns up,” wrote Jim Murray. “It is hard to see how anyone in the Hall of Fame can avoid wincing when they see him coming. I hope they at least have the decency to hide their plaques.”46

By 1966, Paige’s pitching career had mostly come to an end (though he might not have admitted it). With more time on his hands, and the outcry over his continued shunning by the Hall of Fame, Paige was often called upon the weigh in on the issue of the day.

- 1965: “Truly, I think I belong in the Hall of Fame. I don’t want to do no braggin’ on myself you understand, but all the big wheels call me the greatest that ever lived.”

- 1968: “They don’t say I’m not worthy. That’s the real test—if I’m worthy or not. Put it to a vote of the people and they’ll put me in there—you know that.”

- 1969: “The whole world wants me in it. But I didn’t play in the major leagues long enough— that’s how it’s wrote up, even though for years and years I was the world’s greatest pitcher. But I’m not saying they’d change the rules for me. Maybe someday before I die I could sorta sneak in. You know, for good conduct or something like that.”49

Dizzy Dean, like Bob Feller, had barnstormed with Paige for many years and knew him well. Dean had been praising Paige’s talents for many years and weighed in to Jet magazine in 1968: “I pitched about 12 years against Satchel from coast to coast. He is one of my finest friends—a guy I appreciate being with and playing against and associating with. I certainly think that if anybody belongs in the Hall Fame it is Satchel Paige. He was one of the outstanding pitchers of all times and a guy who has given his life to baseball.”50

After years of stalemate, in July 1969 the baseball writers finally made a move to break the logjam, creating a committee of experts to recommend the induction of Negro League stars. The plan was announced by BBWAA president Dick Young during induction weekend for Stan Musial, Roy Campanella, Stan Coveleski, and Waite Hoyt. The plan had been proposed by Larry Claflin of Boston and passed overwhelmingly.51 This committee had no authority, but the writers were hoping to force the issue.

“Certainly no one questions the credentials of [the newest inductees],” said Young, “but there are questions to be asked. Why Waite Hoyt and Stan Coveleski, and not Satchel Paige? Why Roy Campanella and not Josh Gibson?” Campanella immediately volunteered to be part of the committee. Young pledged that the writers would work closely with commissioner Kuhn and Hall president Paul Kerr.52

Another key event in this story was the 1970 publication of Robert Peterson’s Only the Ball was White. Much more than a scholarly study of the Negro Leagues, the book made the case that the leagues were as good, as valuable, and as historically rich as any baseball that had ever been. The book opens with an excerpt from Ted Williams’s Cooperstown speech and closes with capsule biographies of several dozen Negro League stars. “So long as the museum excludes some of these greats,” wrote Peterson, “the notion that it represents the best in baseball is nonsense.”53

The Hall of Fame finally lifted a finger for the Negro Leaguers on February 1, 1971, when Kuhn and Kerr announced the formation of a special committee of ten Negro Leagues experts who would select one Negro League player per year. The honoree would get a plaque that would be hung in a special exhibit. The new committee most prominently included Campanella, Monte Irvin, Judy Johnson, Alex Pompez, Sam Lacy, and Wendell Smith.54

Alarmingly, no one was claiming that these honorees would be Hall of Fame members. “It was not their fault they didn’t play in the majors,” admitted Bowie Kuhn, before countermanding his own point. “We can’t make them real members because they don’t qualify under the rules.” Countered one writer: “So they will be set aside in a separate wing. Just as they were when they played. What an outright farce.”55

Surprising no one, Paige was the first selection just over a week later, on February 9. Hastily assembling for the press at Toots Shor’s restaurant in New York, Kuhn and Paige, who was accompanied by his wife LaHoma, each spoke briefly, and the press asked questions—most of them concerning the separate display. Where would it be? How would the plaques compare to the “real” plaques? Kuhn had no answers, and Paige seemed embarrassed. “Technically,” admitted Kuhn, “he’s not in the Hall of Fame. But I agree with those who say that the Hall of Fame is a state of mind and the important thing is how sports fans view Satchel Paige. I know how I view him.”56

Kuhn’s words satisfied no one, of course. Smith and Lacy, who had covered and celebrated the Negro Leagues their entire lives, put on a brave face and defended the plan. Smith suggested that this segregation could be temporary.57 For the time being, the acknowledgment of the greatness of players who had, after all, not played in the major leagues, was a fine compromise.

The reaction was unpleasant. Jim Murray, for one, was furious:

To have kept Satchel Paige from playing in the white leagues for 24 years, and then bar him from the Pearly Gates on the grounds that he didn’t play the required 10 years is a shocking bit of insolent cynicism, a disservice to America. What is this—1840? Either let him in the front of the Hall—or move the damn thing to Mississippi.58

“It’s not worth a hill of beans,” said a frustrated Jackie Robinson. “If it were me under those conditions, I’d prefer not to be in it. Rules have been changed before. You can change rules like you changed laws if the law’s unjust. Satch’s contributions deserve the Hall of Fame. Why does it have to be a special Black thing?”59

So, whose idea was this, and why didn’t they see all this anger coming?

In 1971 there were 14 men on the board of directors: eight baseball people (Ford Frick, the board chairman; commissioner Kuhn; league presidents Joe Cronin and Chub Feeney, ex-league presidents Warren Giles and Will Harridge; and executives Tom Yawkey and Bob Carpenter) and six Hall directors, local men who ran the Hall foundation.60 Ten votes were needed to change the rules. According to Dick Young, who spent two years fighting for this cause, the directors most adamant against admitting Negro Leaguers were Frick, Hall President Paul Kerr, and all the other Cooperstown people. Other than Frick, all the baseball people wanted full admittance for the Negro Leaguers.

“There were some pretty good shouting matches,” revealed Young, “involving directors of the Hall of Fame, Commissioner Kuhn and a representative of the BBWAA, the organization which had originated the drive.”61 Kuhn later told a similar story in Hardball, his memoir, agreeing that Frick and Kerr were the roadblocks, and adding the detail that the writer was Young himself. “Young was passionate and unrelenting in support of admitting Black players. Though I categorically agreed with his argument, I was offended by his rudeness to Frick.”62

Young also revealed that Hall officials had suggested that it would not merely have a separate wing, but it would have two ceremonies—with the Negro League induction happening on a different date. For their part, the writers threatened to break with Cooperstown and set up their own Hall.63

Kuhn claimed in Hardball that he had pushed for the wing compromise fully knowing that the public outcry would cause Kerr to cave in. This explanation might be self-serving, though it also might be true. Most of the criticism through the decades has been aimed at Kuhn, rather than the Hall, which is almost certainly backwards.

In early July, just a month before the induction, the Hall caved. Kuhn announced that Paige would be inducted as a full member, one of eight honorees. (The others were Dave Bancroft, Jake Beckley, Chick Hafey, Harry Hooper, Joe Kelley, Rube Marquard, and George Weiss.) “I didn’t have no kick or no say when they put me in that separate wing,” said Paige. “But getting into the real Hall of Fame is the greatest thing that ever happened to me in baseball.”64

On August 8, the day before his induction, Paige sat on the terrace at Cooperstown’s famed Otesaga Hotel and reflected on his long road. “Isn’t this something?” the great man asked. “Here I am, a guy who just loved baseball, still loves it. I played because it was all I ever wanted to do. I had no idea where it would take me—and it brought me here to the Hall of Fame.”65

“People ask me how I feel about all this. It’s the big day of my life, but it’s hard to talk about. I could play ball in a town but I couldn’t eat there. … But that didn’t bother me that much. I never had nothing but that. And I don’t want to stir up nothing now. I pure love baseball, and I don’t want to do nothing to hurt it.”66

The next day, Paige finally had his great moment on the steps of the Hall of Fame library. “I am the proudest man on earth today,” said Paige. “and my wife and sister and sister-in-law and my son all feel the same. It’s a wonderful day and one man who appreciates it is Leroy ‘Satchel’ Paige…Since I’ve been here I’ve heard myself called some very nice names. And I can remember when some of the men in there called me some bad names when I used to pitch against them.”67

There were reportedly 3,000 people at the ceremony, mainly sprawled out in Cooper Park outside the library. There were three other inductees present (Hafey, Hooper, and Marquard), though Paige was surely the most famous and the most remembered. Bill Veeck made the trip, of course. “Satch is the reason I am here,” said Veeck. “You have to remember he supported us in several places. The least I can do is show here today.”68

Paige praised his old friend from the podium. “They wanted to run both Bill and me out of town in 1948,” he said. “There was a writer who even said I was too old to vote but I guess, Bill, I got us both off the hook today.”69

Among the less famous observers were 16 men who had traveled to Cooperstown for an additional purpose. These men would meet again the next day, Tuesday, August 10, in the Hall of Fame library to create the Society for American Baseball Research. The Negro Leagues Committee, one of SABR’s original research committees, was formed a few weeks later.

MARK ARMOUR is a baseball researcher and writer living in Corvallis, Oregon. He founded SABR’s Baseball Biography Project and its Baseball Cards Committee.

NOTES

1 Drew Silva, “Throwback: Ted Williams’ Hall of Fame speech,” https://www.nbcsports.com/mlb/news/throwback-ted-williams-hall-of-fame-speech.

2 Charles Livingston, “Williams Praises Negro Stars,” Louisville Defender, August 11, 1966, a8.

3 Roger Birtwell, “Ted Batted Only .091 vs. Boyhood Idol,” Boston Globe, July 26, 1966, 25.

4 Jimmy Burns, “Spotlighting Sports,” Miami Herald, August 9, 1956, 49.

5 Paul McFarlane, “Ted Unlocks Flood of Memories,” The Sporting News, February 5, 1966, 3–4.

6 For example, see Joe Williams, Pittsburgh Press, July 2, 1952, 22.

7 Bob Feller as told to Edward Linn, “The Trouble with the Hall of Fame,” Saturday Evening Post, January 27, 1962, 49. Feller has been criticized for suggesting in 1946 that he had seen few Negro League players who would succeed in the major leagues. His pessimism even extended to Jackie Robinson, who Feller believed was too muscle-bound to be able to hit fast pitching. Feller was inducted into the Hall of Fame with Robinson, and in the Saturday Evening Post Feller freely admitted— “It pains me to confess this”—his misjudgment.

8 Tom Scanlan, “Second Guess,” Army Times, January 27, 1953, 28.

9 Art Carter, “From the Bench,” Baltimore African-American, January 7, 1939, 7.

10 Peter Suskind, “’Satch’ Lets Himself Out,” Norfolk Journal and Guide, August 15, 1942, 14.

11 ANP, Kansas City Call, February 7, 1947.

12 Joe Williams, “Evans Says Groth Better Than DiMag,” Worcester Evening Gazette, February 13, 1950, 21.

13 Joe Bostic, “There Are Some Missing Names in the BB Hall of Fame,” New York Amsterdam News, February 10, 1951, 25.

14 For example, see “Hall of Fame Next Stop for Ageless Satchel Paige,” New York Age , July 5, 1952, 27.

15 Marty Richardson, Cleveland Call and Post, “Let’s Have Some Sports,” July 19, 1952, 7A.

16 Russ Cowans, “Paige Should Be In the Hall of Fame,” Chicago Defender, August 30, 1952, 16.

17 John I. Johnson, “Mighty Old Mound Master,” Kansas City Call, September 26, 1952, 10.

18 “Selkirk,” Milwaukee Journal, July 16, 1952, 37.

19 Bob Murphy, “Jerry McCarthy Has Great 2-Year-Old,” Detroit Times Extra, August 7, 1952.

20 Gayle Talbot, “Ageless Satchel Paige Gets Nomination for the Hall of Fame,” Abilene Reporter-News, August 18, 1952, 8.

21 Cy Rice, “National Sports Editors Poll,” Arkansas State Press, November 14, 1952, 4.

22 Gayle Talbot, “Sports Roundup,” Hattiesburg American, August 18, 1952, 9.

23 Buddy Chambers, “Speaking of Sports,” Monroe Journal, June 30, 1955.

24 Ed Fitzgerald, “Let’s Get Old Satch into the Hall of Fame!” SPORT, November 1962, 9.

25 Dan Daniel, “Terry, Dean Rapping on Door of Hall of Fame,” The Sporting News , February 6, 1952.

26. L. B. Davis, “Sports,” Wichita Post-Observer, August 14, 1953, 7.

27 Joe Williams, “Sports Comment,” Huntsville Times, January 18, 1953, 27.

28 Dan Daniel, “Pilots, Umps Get Shrine Recognition,” The Sporting News, August 5, 1953, 1.

29 Ray Gillespie, “Changes Adopted in Balloting Rules for the Hall of Fame,” The Sporting News, July 25, 1956, 2.

30 “Clark Heads Hall of Fame,” Oneonta Star, August 13, 1958, 13.

31 Editorial, The Sporting News, September 26, 1956, 12.

32 Joe Williams, “After Years and Years of Skid-row Baseball, Hall of Fame for Satchel,” Buffalo Evening News, August 21, 1956, 10.

33 Jim Murray, “Baseball’s Greatest?” San Jose News, June 22, 1964, 16.

34 Wendell Smith, “Satchel Paige Still a Man of the Road,” Pittsburgh Courier, January 9, 1965, 23.

35 Bob Sudyk, “Too Bad They Can’t Bend Rules for Satchel,” The Sporting News, December 19, 1964.

36 Sudyk.

37 Joe McGuff, “Paige Will Pitch In Finley’s Next Novelty Number,” The Sporting News, September 25, 1965, 23.

38 Bill Bishop, “Casey Stengel,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/casey-stengel/.

39 Clifford Kachline, “Give Ol’ Perfessor Hall of Fame Spot Now, Writers Urge,” The Sporting News, December 18, 1965, 12.

40 Oscar Kahan, “Will Rickey Be Barred from Shrine?” The Sporting News, December 25, 1965, 1.

41 Kahan.

42 A. S. Doc Young, “A Vote for Satch,” New York Amsterdam News, March 26, 1966, 33.

43 A. S. Doc Young, “I Had a Good Idea,” Chicago Daily Defender, August 10, 1966, 24.

44 BPJ, “Ted Makes Hall of Fame as a Real Human Being,” Los Angeles Sentinel, August 11, 1966, B1.

45 Walter Hoye, “Ted Williams Says Paige and Gibson Were the Greatest,” Michigan Chronicle , August 20, 1966, A23.

46 Jim Murray, “Old Satchel Puts Baseball to Shame,” Detroit Free Press, February 5, 1966, 22.

47. Joe McGuff, “Paige Will Pitch in Finley’s Next Novelty Number,” The Sporting News , September 25, 1965, 23.

48. John Crittenden, “Marking a Ballot for Favorite Son,” Miami News, September 4, 1968, 29.

49 “The Great Satchel Paige: ‘New Generation Taking Over’,” Poughkeepsie Journal, March 30, 1969.

50 Robert E. Johnson, “Dizzy Dean Makes Pitch to Get ‘Satch’ Paige in Hall of Fame,” Jet, March 14, 1968, 52.

51 Dick Young, “Brooklyn Atmosphere at Hall of Fame Induction,” August 9, 1969, 5.

52 Young, “Brooklyn Atmosphere.”

53 Robert Peterson, Only the Ball Was White (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1970), 254.

54 “Place for Ex-Negro Stars in Shrine,” The Sporting News, February 13, 1971.

55 Wells Twombly, The Sporting News, February 20, 1971, 41.

56 Phil Pepe, “Old Satch Makes Hall of Fame, Natch,” Daily News, February 10, 1971, 55.

57 C. C. Johnson Spink, “we believe…,” The Sporting News, February 27, 1971, 17.

58 Jim Murray, “J. Crow Enters Baseball Heaven,” Boston Globe, February 15, 1971, 19.

59 Milton Gross, “Black Isn’t So Beautiful In Baseball Hall of Fame,” High Point Enterprise , February 9, 1971.

60 “Broeg succeeds Stockton on Cooperstown Group,” The Sporting News, August 28, 1971, 33.

61 Dick Young, “Young Ideas,” Daily News, August 6, 1971, 107.

62 Bowie Kuhn, Hardball—The Education of a Baseball Commissioner (New York: Times Books, 1987), 110.

63 Young, “Young Ideas.”

64 UPI, “Satchel Paige Is Accorded Full Hall of Fame Honor,” Casper Star-Tribune, July 8, 1971, 16.

65 Dick Wade, “Satchel Looks Back,” Kansas City Star, August 9, 1971, 12.

66 Wade.

67 Bill Francis, “Paige’s Induction in 1971 Changed History,” Baseball Hall of Fame website, https://baseballhall.org/discover/baseball-history/paiges-induction-changed-history.

68 Dick Wade, “Paige Enters Hall,” Kansas City Star, August 10, 1971, 18.

69 UPI, “Satchel Paige Pays Tribute to Bill Veeck,” Lansing State Journal, August 10, 1971, 17.