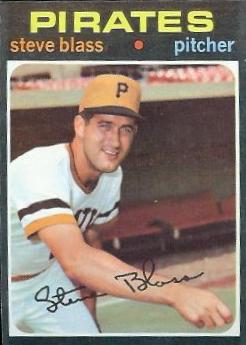

Steve Blass

Shortstop Jackie Hernandez glided behind second base, smoothly picked up Merv Rettenmund’s ground ball and with one easy motion flipped it across the diamond to first baseman Bob Robertson for the final out of the 1971 World Series.

Shortstop Jackie Hernandez glided behind second base, smoothly picked up Merv Rettenmund’s ground ball and with one easy motion flipped it across the diamond to first baseman Bob Robertson for the final out of the 1971 World Series.

“[The] catcher is running toward the camera at full speed, his upraised arms spread wide. His body is tilting toward the center of the picture, his mask is held in his right hand, his big glove is still on his left hand and his mouth is open in a gigantic shout of pleasure.”

Thus Roger Angell described the celebrant mood of that year’s fall classic. It is also a moment that will forever be frozen in time by Rusty Kennedy’s Associated Press photograph. The leaping player is Steve Blass; Manny Sanguillen is the Pittsburgh Pirates’ catcher.

“Clemente was great all right, but if it hadn’t been for Mr. Blass, we might be popping the corks right now!” Earl Weaver, the combative manager of the Baltimore Orioles, uttered. Weaver was the same man who interrupted the first inning of the final game, questioning where Blass was standing on the rubber before delivering the ball. Weaver cited a rules violation; others perceived it as an attempt to rattle the young and excitable pitcher. History will show that Mr. Weaver did not succeed on either count. Blass settled down, and the Pirates won the final game of the series by a score of 2-1!

Steve Blass was born on April 18, 1942, in the rural town of Canaan, Connecticut. He was the son of a plumber. The Blass homestead included a barn with an interestingly angled roof, against which a young Steve would play hundreds of one-man games with a tennis ball. “I had all kinds of games, with different, very complicated ground rules. I’d throw the ball up and then dive into the weeds for pop ups or running back and calling for long fly balls and all. I’d always play a full game. A made-up game, with two major league teams and I would write down the line score as I went along and keep the results. One of the teams had to be the Indians. I was a total Indians fan, completely buggy. In the summer of 1954, when they won the record of one hundred and eleven games, I managed to find every single Indian box score in the newspaper and clip it out, which took some doing up where we lived. I guess Herb Score was my real hero — I actually pitched against him once in Indianapolis in 1963, when he was trying to make a comeback — but I knew the whole team by heart. (Ed note: Score joined the Indians in 1955.) Not just the stars but also all the guys on the bench like George Strickland, Wally Westlake and Hank Majeski. My first big league autograph was Hank Majeski.”

Steve would be one of the fortunate few who would transfer his love for the National Pastime onto the diamond. A good athlete, he also excelled on the court and gridiron. He was chosen to the All-State Class B, second team in basketball. Then during his junior year at Housatonic Regional School, he tossed two no-hitters. He added three more as a senior. It might have something to do with his bloodline. His Dad, Bob Blass, was a semi-pro pitcher around Canaan, Connecticut. It was said that Bob Blass was “wilder than Hell.” A local legend was that he once threw a ball over the backstop.

While on his high school squad, Steve would be a teammate of his future brother-in-law. John Lamb was also a pitcher and would eventually play for the Pittsburgh Pirates. Not only would they become teammates in Pittsburgh, Steve would marry John’s sister Karen, his high school sweetheart, during the fall of 1963. That winter the newlyweds flew to the Dominican Republic, where Steve played for the Cibaenas Eagles. It was during this period that Steve worked on his slider.

Pirates scout Bob Whalen signed Steve right out of Housatonic High School in 1960. His beloved Cleveland Indians offered him a $2,500 bonus, but they wanted him to wait until the next spring training to start. The young man decided on the Pirates, mainly because they were willing to pay him $4,000 and put him in their minor leagues immediately. Of course it did not hurt that Ed Kirby, his high school coach, also doubled as a scout for the Pittsburgh club. Steve played for five years and six different teams before becoming a fixture with the parent club. Blass credits the club’s roving pitching instructor Don Osborne as his mentor. “He helped me with guidance in terms of how to handle pro ball. He preached the simplicity of pitching, because as a youngster you try to complicate things. He helped me to trust my stuff, get the ball over the plate and find out if you’re good enough.”

Blass’ best season in the minors was with the 1962 Kinston Eagles of the Class B Carolina League. He was a member of the league’s all-star team along with some other successful future major leaguers: Rusty Staub, Cesar Tovar, Tony Perez, Rico Petrocelli and Mel Stottlemyre. Blass finished with a 17-3 record, a 1.97 ERA and 209 strikeouts in 178 innings.

In 1964, Blass was invited to spring training but was sent to the Pirates’ AAA affiliate in Columbus, Ohio. The young pitcher would not stay there for long. Three weeks later he was called up the parent club. Excitement did not fully describe his joy at the promotion: “We got in the car, and I floored it all the way across Ohio. I remember it was raining as we came out of the tunnel in Pittsburgh, and I drove straight to Forbes Field and went in and found the attendant and put my uniform on at two in the afternoon. There was no game there or anything — I just had to see how it looked.”

After a relief appearance againt Milwaukee on the 10th, Blass’ first start came on May 18, 1964, at Dodger Stadium against future Hall of Famer Don Drysdale. He would win, 4-2, for his first major league victory and complete game. Blass says about his first victory: “It was a dream come true. I had been around several days and had pitched a time or two in relief. Drysdale was 5-1 at the time and I looked up at the scoreboard and he was leading the league in just about everything. What I remember about the game was Leo Durocher was their third base coach at the time and he was screaming at me, using language that I had never experienced before; he was trying to rattle me. It certainly ended up being a wonderful thrill.” Steve finished his rookie campaign at 5-8 with a 4.04 ERA. He would not return in 1965, spending the entire year at Columbus of the International League.

The plumber’s son from rural Connecticut came up to the Pirates for good in 1966. He displayed major league stuff, razor-sharp control, a 90-MPH fastball and a slider that he would place on the first base side of home plate. Blass was so confident in his slider that he threw it even when he was behind in the count. Blass thanked the Pirates for their faith in him with an 11-7 record and an ERA of 3.87. The Pirates finished in third place with a 92-70 record, three games behind the Los Angeles Dodgers.

He fell to 6-8 the following year despite an improved ERA of 3.55. The Pirates limped to an 81-81-season and drop to sixth in the ten-team league. Manager Harry Walker was fired with a 42-42 record and replaced by Danny Murtaugh, who had guided the team to a World Series victory in 1960. On his second tour of duty, Murtaugh ended the year winning as many games as he lost, showing no improvement over Walker.

Then in 1968, Blass established himself as the team’s ace. He put up an 18-6 record with an ERA of 2.12 and lead the National League with a winning percentage of .750. In September he threw three consecutive shutouts and at one point won nine straight starts. On August 31, 1968, Steve started a game against the Atlanta Braves, got the first out, and then moved to left field. Long-time Pirate reliever Elroy Face came in to retire Felix Millan and tie Hall of Famer Walter Johnson’s major league record of 802 pitching appearances with one club. Blass returned to the mound and the Pirates went on to win 8-0. He did not get credit for the shutout although he would finish third in the National League with 7 shutouts. Late in the game, the Pirates announced that Face has been sold to the Detroit Tigers. Then on September 24, 1968, Blass recorded his third shutout in a row, beating the Reds 2-0. Even with Blass’ superb year, the Pirate produced a losing record of 80-82 under the guidance of Larry Shepard.

Baseball fans witnessed a true fairy tale in 1969, when the New York Mets won the National League’s Eastern Division. They went on to defeat the Atlanta Braves in the League Championship and upset the heavily favored Baltimore Orioles in the World Series. The Pirates finished in third place behind both the Mets and Cubs with an 88-74 record. Blass contributed a 16-10 record, but with a 4.46 ERA, the highest full-season ERA of his career. Larry Shepard was dismissed with five games left in the season.

While Steve did not have his best pitching year in 1970, his work was still respectable as Pittsburgh captured the Eastern Division behind a rotation that featured Luke Walker, Dock Ellis, Bob Veale, Bob Moose and Blass. Steve finished the season with a record of 10-12, and an ERA of 3.52 with one shutout. The Pirates lost three straight games to the Cincinnati Reds for the National League pennant.

The 1971 season would be the Pirates’ first full year in Three Rivers Stadium. It was also the first season that a Pirate team led the circuit in home runs, belting 154 while leading the majors with 788 runs scored. Prior to the season the Pirates traded one of their best hitters over the last few years: Matty Alou was sent to the Cardinals for Vic Davalillo and Nelson Briles. This deal provided Pittsburgh with two very important pieces to their World Championship season. The team itself was multinational and multiracial, with seven African-American and six Latin American players, an uncommon mixture in the major leagues during this era.

Steve Blass put together a 15-8 record with a 2.85 ERA, and tie Bob Gibson for the lead in shutouts (5) in the National League. Such numbers could be considered a successful season, but it was in the postseason where his star would really shine.

The 1971 postseason did not start out well for Pittsburgh. The Pirates faced the San Francisco Giants for the National League championship. Blass pitched the first game and was roughed up, losing 5-4. Tito Fuentes and Willie McCovey delivered home runs in the fifth inning to overcome a 2-1 deficit. Gaylord Perry earned a complete-game victory. Blass also pitched poorly in the fourth game, but his team rallied to close out the game and the series. “I got my brains beat out and my confidence was a little eroded. This was my first postseason performance and I thought I had to be different in the postseason, better than I was in the regular season. I tried to overpower hitters and that wasn’t my game. By game 3 of the World Series, I learned my lesson: be yourself and go with what got you there.”

The Pirates defeated the Giants three games to one and headed to Baltimore to face the powerful Orioles in the World Series. Pittsburgh dropped the first two games.

The teams went back to Pittsburgh for games three, four, and (they hoped) five. Steve redeemed himself with a sparkling performance. He allowed three hits by the Orioles, including a solo home run by Frank Robinson that accounted for the lone Baltimore run in the 5-1 game. This was also the game in which Clemente tried to call time because Bob Robertson missed the bunt sign while smacking a homer cementing a Pirate victory.

The teams battled to split the first six games, which led to the decisive seventh game match-up featuring the same starters as game three. Pirate manager Danny Murtaugh chose Blass while Earl Weaver picked Mike Cuellar. At first, things did not look promising for the 29-year-old. Blass was uncharacteristically wild in the first inning, walking leadoff man Don Buford. Weaver seized the opportunity to rattle the Pirate pitcher. He ran out onto to the field to complain that Steve was in violation of Rule 801, which simply states that the pitcher must throw from the front of the rubber and he accused Blass of throwing from the side. Weaver’s strategy backfired. Instead of unsettling the excitable Bucco pitcher, it seemed to calm him. Steve found his groove. “I thank Earl every time I see him. In the first inning I was all over the place until Earl came out and it calmed me down with his nonsense. As the game went on I got settled into the contest.”

Blass only gave up another single, in the eighth inning. “I took a moment in the bottom of the seventh after I warmed up and before the first pitch. I took the baseball and went to the back of the mound to take in the whole scene. You don’t know if you’ll ever get back again, and I wanted to soak in the mental image, then we went back to work.”

Jim O’Brien shares a little known story in We Had ‘Em All the Way, his book about legendary Pirate announcer Bob Prince. Steve, on the brink of the greatest moment of his baseball career, went down to the visiting clubhouse in Baltimore while his teammates batted in top of the ninth inning. He was trying to kill time before returning to the mound. Blass spotted Prince in the clubhouse and basically told him to get out because he had some unfinished business.

Blass puts the experience in perspective: “We won the World Series, I was the winning pitcher in the deciding game. That is the stuff you dream about as a kid. Hitting a homerun to win the World Series as Maz did in 1960 or throwing the final pitch to close it out as I did.”

In comparing the relative heroes of the 1971 series, Roger Angell wrote: “I remembered the vivid contrast in styles between the two stars … Clemente, at last the recipient of the kind of national attention he always deserved but was rarely given for his years of brillant play … Blass was a less obvious hero — a competent but far from overpowering right-hander who had won fifteen games for the Pirates that year, including a most respectable 2.85 earned run average, but who had absorbed a terrible pounding by the San Francisco Giants in the two games he pitched in the National League playoffs, just before the Series…”

This might be the reason Blass celebrated more exuberantly than Clemente, exchanging hugs and shouts with teammates, smoking a cigar and swigging champagne. Blass also shared the moment with his dad. Clemente, in Spanish, asked for his parents’ blessing on national television.

The following year was Blass’ finest regular season at the major league level. Bill Virdon, his manager that year, claims that if it were not for Steve Carlton’s extraordinary season for the last-place Phillies, Blass would have captured the Cy Young award. In 1972, Steve established himself as the undisputed ace of the Pittsburgh pitching staff, finishing 19-8 with an ERA of 2.49. He was denied his twentieth win when the Mets chased him in the first inning on October 1. Blass finished sixth in the National league with his earned run average. He was selected to pitch in the All-Star Game, and allowed one run in his only inning of work. Steve completed 11 of 32 games that he started, averaging 7 1/3 innings per start. That year, Steve Carlton had 30 complete games and Bob Gibson 23. Steve was not a flame-thrower in their class. As Roger Angell documented in the New Yorker, the word around the league described him as “Good but not overpowering stuff, excellent slider, good curve, good change up curve. A pattern pitcher, whose slider works because of its location, no control problems. Intelligent, knows how to win.”

The Pirates lost to the Cincinnati Reds that year for the National League championship. It wasn’t Blass’ fault, as he went 1-0 with a 1.72 ERA. Roger Angell described Steve’s pitching motion and stance during that series: ” … A feet together stance at the outermost, first base edge of the pitching rubber and then the pitch, delivered with a swastika like scattering of arms and legs and a final lurch to the left and I also remember how I kept thinking that at any moment the sluggers of the ‘Big Red Machine’ would stop over striding and over swinging against such an underestimated series of deliveries and drive Blass to cover.”

For the Pirates and all of baseball, the year 1972 ended with the tragic death of Roberto Clemente on New Year’s Eve.

At Clemente’ s funeral in Puerto Rico, Steve demonstrated how he was more than just a baseball player. Blass delivered an eloquent, moving eulogy, concluding:

Let this be a silent token

Of lasting friendship’s gleam,

And all that we’ve left unspoken —

Your friends on the Pirate team.

“I don’t think we as teammates knew him as well as we could have,” Blass has said. “He was so much more than a great baseball player.”

While he and his teammates mourned the tragic loss of their spiritual leader, in just months the Pirate pitcher would experience the beginning of his own tragedy. During spring training in 1973, Blass pitched well at the Pirates’ spring home in Bradenton, Florida. The performance was a bit abnormal; historically Steve was a slow starter. No one was concerned, though, figuring it was a continuation of 1972. Blass was selected to pitch Opening Day against the Cardinals. He allowed five runs in five innings, though his team ended up winning the game. After one good start, on April 22 against the Cubs, he gave up a walk, two singles, a homer and a double all in the first inning. Steve sailed through the second but would walk one and hit two batters in the third and was removed

Blass rebounded and tossed a complete-game victory over the Padres, but he then reverted back to a wildness that resulted in an inability pitch more than half of the game against the Dodgers and Expos. By early June, his record was 3-3 with an inflated ERA and high walk totals that suggested serious problems. Bill Virdon, Steve’s friend and manager, displayed the patience of a saint. The skipper reminded Steve that this was not the first time he’d begun a season badly. In 1970, Steve started off with a record of 2-8 but finished the year at 10-12. Steve was in excellent physical shape and his arm felt great, making the ordeal so mystifying. In his entire career, he never had a sore arm. During this period, pitching mechanics came under scrutiny. Maybe he was dropping his elbow, or he seemed to be hurrying his motion, or perhaps his right arm wasn’t in synch with the rest of his body.

Blass returned on June 6 and again on June 11 to pitch against the Braves. In the latter effort, he lasted 3 1/3 innings and gave up seven singles, a homer, and two walks resulting in five runs. Steve agreed with his manager to a stint in the bullpen. Two days later, he came into the fifth inning of a game the Pirates were losing 8-3. He walked two, gave up a stolen base, threw a wild pitch and allowed a run scoring single before retiring the side. The following inning he walked Darrell Evans and Mike Lum, and Dusty Baker singled in a run. After Ralph Garr grounded out, Davey Johnson drove in another run with a single. Marty Perez walked, and pitcher Ron Reed drove in two more with another single. Blass followed with a wild pitch, a walk, and another single, allowing two more to score.

Steve recalled: “It was the worst experience of my baseball life … I don’t think I’ll ever forget it. I was embarrassed and disgusted. I was totally unnerved. You can’t imagine the feeling that you suddenly have no ‘idea’ what you’re doing out there, performing that way as a major league pitcher. It was kind of scary.” He was used sporadically the next several weeks.

Virdon gave him the start on August 6 in the Cooperstown Hall of Fame annual exhibition game played between the Pirates and Texas Rangers, hoping that the less meaningful game might help him work things out. Unfortunately, Blass was as wild as ever and had to be relieved after 2 1/3 innings. Virdon announced that Steve would not start again for the duration of the season. After all, the Pirates were in the midst of a pennant race.

Later that season, Danny Murtaugh was brought back again to manage and gave Steve a start against the Cubs on September 11. The Cubs won 2-0, but Blass allowed only 2 hits and one run in 5 innings. It appeared that his personal nightmare might be over. He followed this performance with another good outing against the Cardinals but finished the season with a bad one against the Mets. In that game he lasted 2/3 of an inning, giving up 4 runs on a walk and four hits. This dropped the team out of first place. He finished 1973 with a 3-9 record and a 9.81 ERA.

The following February, Blass reported to Bradenton with the other pitchers. He attempted to correct the problem. He ended up walking 25 batters in 14 spring training innings. In one outing that spring against the White Sox, he walked 8 men in the fourth; he threw 51 pitches, only 17 of them strikes. He worked a full count on Carlos May, and then threw one behind May’s head. When it became apparent that he could not get the third out, Murtaugh came to take him out. Inexplicably, Murtaugh charged the home plate umpire, cursed him out for a bad call, and was thrown out of the game!

Blass joined the parent club on April 16 in Chicago. He came into the game during the fourth inning, with the Pirates were behind 10-4 and proceeded to pitch 5 innings, give up 8 runs, 3 of them unearned, while allowing 5 hits and 7 walks. Blass was sent down for the rest of the season to the Pirates’ AAA team in Charleston. Things did not get much better in the minor leagues, as he walked 103 batters in 61 innings. He did not return to Pittsburgh.

The most frustrating and bewildering thing about the entire ordeal was that when he threw alone with a catcher, he threw as well as ever. Don Osborn, his former pitching coach, stated that Blass’ problem was mental. In fact, during this time Steve went to a psychologist, and experimented with Transcendental Meditation. He enrolled in a program and was joined by teammates Dave Guisti, Bruce Kison and Willie Stargell.

Finally, after a bad outing during spring training in 1975, the Pirates released him. Steve claimed that the toughest thing he ever had to do was tell his teammates that his career was over.

Steve started his life after baseball first by working for a company that sold class rings, then became a public relations man for a beer distributor. Eventually Blass returned to the game that had been so good to him, where he had experienced his finer moments. Steve became “color man” with the Pirates in 1983. He first broadcast Pirate games on Cable TV for Home Sports Entertainment, serving as Bob Prince’s color man on the telecasts. Steve always shared a special relationship with the “Gunner.” “Bob was one of the people who was behind me during my worst days in baseball. There were several people who stood by me and were so supportive but none more than Bob Prince.”

When Blass was a young player, Prince advised him on how to make public appearances. The veteran broadcaster gave the young ballplayer the following advice: “You’re not going to change the world; you’re a ballplayer. Just make sure you have a tight close to your talk. Don’t stumble around at the end, finish up neat and tidy, that’s what I remember best,” Blass recounted.

Steve did such a good job that the Pirate flagship station, KDKA, hired him in 1986, and he remained a part of their broadcast team for three decades afterward, announcing his retirement following the 2019 season. He has gained the respect of his co-workers. “Steve captures the mood of each game and shares it with the audience. He is quick, humorous and flexible,” offers Lanny Frattare, the longtime Voice of the Pirates.

“Steve Blass brings a great sense of history to the games. His story telling ability is unmatched. He has an incredibly quick wit. He’s one of the funniest people I have ever met. He also teaches without people even knowing it because he’s so light about it,” adds Greg Brown, another peer.

It seems unfair that when Blass’ name comes up, there’s always an account of the malady that ended his pitching career. Any time a pitcher heaves a ball into the stands or walks a couple of batters, someone is sure to bring up “Steve Blass Disease.” Ironically, Blass was a better than average noted control pitcher. He worked batters in the same manner as Catfish Hunter or Tommy John. Steve was a pattern pitcher. He mixed speeds, knew the hitters, remembered their weaknesses and could hit a doorknob from the pitching rubber with his fastball. At the end of 1972, he owned a record of 100-67 for a fine winning percentage of .598. This would rank him among the top 75 pitchers of all time. At the time, Blass had walked only 508 batters while striking out 867.

Sooner or later, anyone who has pitched a baseball from a mound will eventually become ineffective. The human body is fragile, and the psyche is complex. We mistakenly take success for granted instead of remembering that it is fleeting, mysterious and admirable.

Before 1973, Pirate baseball fans would sit in the seats of Forbes Field and Three Rivers Stadium and enjoy a herky-jerky motion that can be likened to a barn full of owls coming at you. That described the delivery of Stephen Robert Blass, the pitcher who lived every boy’s backyard dream — throwing the last pitch while winning the seventh game of a World Series. No one can ever take that away from him.

Last revised: November 11, 2020 (ghw)

Sources

Finoli, David, and Bill Ranier. The Pittsburgh Pirates Encyclopedia. Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 2003.

Markusen, Bruce. Roberto Clemente: The Great One. Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 2001.

McCollister, John. The Bucs! The Story of the Pittsburgh Pirates. Lenexa, Kansas: Addax Publishing L. L. C., 1998.

O’Brien, James P. We Had ‘Em All the Way: Bob Prince and the Pittsburgh Pirates. Pittsburgh: Geyer Publications, 1998.

Peterson, Richard, ed. The Pirate Reader. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2001. (Contains Roger Angell, “Gone for Good)

www.baseballlibrary.com

www.baseball-almanac.com

www.pirateball.com

www.retrosheet.org

www.thebaseballcube.com

www.thebaseballpage.com

Full Name

Stephen Robert Blass

Born

April 18, 1942 at Canaan, CT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.