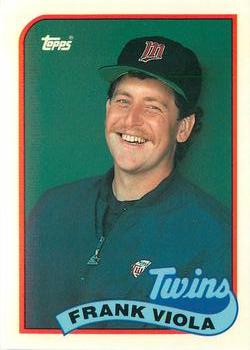

Frank Viola

As a young pitcher, Frank Viola frequently beat himself. But after failing to pitch to his potential for years, Viola learned to get out of his own way. Once he did, the southpaw called “Sweet Music” reached the apex of his profession — he was, inarguably, one of the best pitchers of his era.

As a young pitcher, Frank Viola frequently beat himself. But after failing to pitch to his potential for years, Viola learned to get out of his own way. Once he did, the southpaw called “Sweet Music” reached the apex of his profession — he was, inarguably, one of the best pitchers of his era.

Viola was durable, making at least 34 starts every year between 1983 and 1992. He recorded 176 wins in the majors from 1982 through 1996, including 20-win seasons in both leagues. He earned three All-Star selections, a Cy Young Award, and a World Series MVP trophy.

His career wasn’t quite Hall of Fame caliber, but when it mattered most, on the biggest stage, under the heaviest pressure — Game 7 of the 1987 World Series — he delivered. It turned out the scouts were right: At the peak of his powers, if Frank Viola didn’t beat himself, no one else had a chance.

Frank John Viola Jr. was born April 19, 1960, in Hempstead, New York. He and his brother John and sister Nancy were raised in East Meadow, New York by their father, Frank Sr., and their mother, Helen (née Weindler). Viola recalled that his father, a radio station controller, took him “to 10 Mets games a year and one Yankee game, because he wanted me to know there was another team in town.”1

At a baseball clinic in 1969, Viola heard Mets All-Star pitcher Jerry Koosman discourage pitchers from throwing curveballs when they were young.2 Viola never forgot the advice, even though he did not pitch until his junior year of high school. Before that he was a star first baseman, good enough to be named to the All-Nassau County team as a tenth grader.3 The following year, Viola took the mound for the first time in place of an injured teammate.4 Despite his inexperience, the young lefthander was a dominant pitcher, and during his senior year at East Meadow High he drew attention from scouts.5

Among the scouts was John Schuerholz of the Kansas City Royals.6 The Royals selected Viola in the 16th round of the June 1978 draft, but the lanky lefty wanted to experience college and get a degree.7 He planned to follow in his father’s footsteps and study accounting.8 He was set to attend C.W. Post, a nearby Division II school, but after a tournament game during his senior year of high school, Viola was offered a scholarship by St. John’s University coach Joe Russo.9

If Viola still harbored visions of a Ruthian future of slugging at the plate and slinging from the mound, Coach Russo set him straight: with a left arm that could fire a baseball 95 mph, he should focus on pitching.10 Russo’s direction proved wise — Viola produced a 26-2 record with a sub-2.00 ERA during his St. John’s career. He recalled his time at St. John’s as “the best three years of my life,” and credited his college pitching coach, Howie Gershberg, with teaching him his fluid mechanics.11

The number-two starter for the team, then known as the Redmen, was another future big-league star (and teammate with the New York Mets), John Franco. “That whole team was very close,” Franco said in 1990. “Everybody came from Brooklyn, Queens or Long Island.”12

During his junior season in 1981, Viola started for St. John’s against Yale in what became a legendary NCAA playoff game.13 Viola’s mother had recently suffered a minor heart attack and her doctor ordered her not to attend the game, so she sat at home waiting for someone to call and tell her how the contest turned out. She was completely unaware that her son was locked in an epic pitching duel with Yale righthander Ron Darling.14

Through nine innings, neither team scored. Viola had six strikeouts, Darling ten. Viola had allowed only six hits, Darling none. Extra innings didn’t faze the two aces, who put zeroes on the scoreboard in the 10th and 11th frames, with Darling continuing to hold St. John’s hitless. Finally, in the 12th inning, St. John’s scored the game’s only run after second baseman Steve Scafa blooped a single and then stole second, third, and home.15 Incredibly, Darling was the losing pitcher despite an astounding 11 hitless innings and 16 strikeouts.

A few weeks after that classic game, the Minnesota Twins selected Viola in the second round of the June 1981 draft. Viola knew the Twins wouldn’t offer him much of a signing bonus, but money was less important to him than a quick path to the big leagues, which he figured to have with the lowly Twins.16 After the draft, Viola spent the remainder of the 1981 season at Double-A Orlando. The following season, a mere five years removed from his high school pitching debut, and after making just eight starts at Triple-A Toledo, Viola was called up to the big leagues.

He wasn’t ready.

Viola joined a terrible Twins team that won just 60 games in 1982 and 70 in 1983. Like his team, Viola struggled. His aggregate ERA for the ’82 and ’83 seasons was a bloated 5.38, and he lost 25 games while winning just 11. The losing wore on the young lefthander, who called his dad after every start. Frank Sr. said, “It got to the point where I didn’t even know what to say.”17

In 1984, as the improving Twins took second place in their division, Viola found his footing. In December 1983 he got married to Kathy Daltas, a University of Minnesota graduate student.18 The young couple had their first child in the middle of the 1984 season. Viola’s new status as a family man seemed to anchor the lefthander and he experienced consistent success for the first time in the majors. Twins pitching coach Johnny Podres thought the key was Viola’s decision to pitch fearlessly and throw the ball over the plate.19 Viola himself noted a newfound commitment to each pitch he threw. “I love that idea that when I’m out there I know what I’m doing,” he said. “I’m like a new man.”20

The new Viola picked up a new nickname in 1984, too, as he became the favorite player of Twins fan Mark Dornfield, a bowling alley manager from Woodbury, Minnesota. Dornfield made a bedsheet banner that read “Frankie Sweet Music Viola” and started hanging it in the right field upper deck, just inside the foul pole. “I put it there so [Viola] could see it from the dugout,” said Dornfield.21

Sweet Music finished the 1984 season with an 18-12 record and a 3.21 ERA, good enough for sixth place on the American League Cy Young ballot. His success generated bold predictions. Twins owner Calvin Griffith thought Viola could turn into a 30-game winner.22 And Podres, who had been in the Dodgers’ rotation with Sandy Koufax, compared Viola to the legendary lefty.23

Viola had unlimited potential, but he regressed during the next two seasons. Though he still won 18 and 16 games, his ERA swelled to 4.09 in 1985 and 4.51 in 1986. Viola’s troubles had nothing to do with his arm and everything to do with his head. He could control his pitches but not his emotions. His father noted that scouting reports all said the same thing: “The only person who can beat Frank Viola is Frank Viola.”24

Toronto Blue Jays general manager Pat Gillick said, “[Viola] has the potential to be a 20-game winner on a consistent basis if he can put everything together. When he’s pitching well, you can see that it’s all there. But I also think he’s a guy that always seems to be a bit hyper, a bit too emotional. He’s got to keep that under control.”25

During a May 1986 game in Boston, Viola gave up a leadoff double, and then the next batter, Wade Boggs, was called safe on a close play at first. Viola thought Boggs was out, and when the call didn’t go his way he came unglued. He gave up a walk, a single, and two doubles, and was pulled from the game after giving up five runs and getting zero outs.

Twins pitching coach Dick Such watched the lefty’s volatility cost him again and again. “Frank would let a bad call, a bad pitch, a bad play, a homer, or almost anything set him off.”26 Late in the 1986 season, Such pulled Viola aside and told the talented southpaw that he wasn’t concentrating on what he could control. “You pitch according to how the team plays. If the team’s playing poorly, you pitch poorly. Just do what you do best. Throw the ball. And grow up.”27

Going into the 1987 season, Viola knew it was a make or break year for himself and the Twins. The club had followed the same pattern as Viola, showing great promise in 1984 before backsliding in 1985 and 1986. Before the 1987 season opened Viola said, “I think this is the year to put up or shut up.”28

Viola did his part, establishing himself as one of the best pitchers in baseball. Two changes sparked his transformation: a new attitude and a new weapon.

Viola watched how his teammate, veteran righthander Bert Blyleven, handled adversity without changing his disposition, even when he gave up mammoth home runs. It made Viola think, “Why don’t I just take a lesson from this man?”29 Early in the 1987 season Viola decided “I wasn’t going to let things that I couldn’t control bother me. Errors, bad calls, bad bounces, there’s nothing you can do about it. I finally realized that.”30

Viola paired his new demeanor with a new signature pitch: a devastating changeup. Viola fiddled with a grip that Johnny Podres had taught him years earlier.31 He found that it suddenly worked well for him — so well that his changeup became a lethal weapon. He would throw it in any count to any hitter in any situation. In a game against Seattle he picked up three straight outs — two strikeouts and a groundout — by throwing nine consecutive changeups.32

The new version of Viola finished the 1987 regular season with a 17-10 record, a 2.90 ERA, and a sixth place finish in the American League Cy Young race.

And he wasn’t done.

Like Viola, the Twins made a leap in 1987, winning their division and beating the heavily favored Detroit Tigers in the American League Championship Series to set up a World Series showdown with the St. Louis Cardinals.

Viola was on the mound to start Game One of the Series in front of a deafening crowd at the Metrodome in Minneapolis. He dominated the Cardinals, giving up just one run in eight innings. He issued no walks and reached a three-ball count with only two batters. After the game, baseball writer Roger Angell spotted Viola “with a towel around his neck, a can of beer in each paw, and an inextinguishable grin on his face.”33

Viola’s grin vanished during his Game Four start, when he got only ten outs and gave up five runs, taking a loss that evened the Series at two games apiece. The backbreaking blow was a three-run bomb from weak-hitting Tom Lawless, only the second big-league homer he’d ever hit. On the ABC telecast an astonished Al Michaels said, “Did we really see that?”34

Another Twins loss in Game Five put them down three games to two as they headed back home for Game Six. Viola urged his teammates to force a Game Seven — which he would start — telling them, “I want the ball.”35

The Twins prevailed in Game Six, so Viola got what he wanted. But what he needed was his lucky “Frankie Sweet Music Viola” banner. He was 16-0 with the banner hanging, so he made sure his wife got his superfan, Mark Dornfield, two tickets for Game 7.36

The banner didn’t help Viola early in Game Seven. He fell behind 2-0 in the second inning and saw Bert Blyleven warming up in the bullpen. Earlier in his career Viola might have unraveled in this situation, but now he was able to control his emotions. He proceeded to shut down the Cardinals through the eighth inning as his teammates rallied to take a 4-2 lead. Twins closer Jeff Reardon finished off the Cardinals in the ninth, securing Minnesota’s first World Series title. Viola, the winner of the first and seventh games, was named World Series MVP.

After his postseason heroics, Viola went into the 1988 season brimming with confidence. He was armed with an arsenal of pitches, including a good fastball and what scouts generally considered the game’s premier changeup.37 It was enough to make hitters feel helpless. “When he gets ahead of you in the count, the feeling is unbelievable,” said Cal Ripken. “He has so many pitches at so many speeds and such command of them all that you don’t know what to look for.”38

After a dominant first half of the season, Viola started for the American League in the 1988 All-Star game. He tossed two perfect innings on his way to picking up the win.

Viola continued to pitch well in the second half of the season and finished with a career-high 24 wins and a 2.64 ERA. He chewed up 255⅓ innings for the Twins, including a team record 30⅓ consecutive scoreless frames.39 Detroit Tigers manager Sparky Anderson — whose club was dominated by Viola three times that year — gushed about the lefthander, calling him an artist.40 He also said, “Someone should be shot if he doesn’t win the Cy Young Award.”41

As it turned out, no gunfire was necessary when the American League Cy Young winner was unveiled: Viola won in a landslide, garnering 27 of 28 first place votes.

Viola was on top of the world, and the East Coast native had found a comfortable home in Minnesota. In an August 1988 Sports Illustrated profile, he said “I’ve become a Minnesotan who lives in Florida in the off-season. I wouldn’t want to go back to New York now.”42

One year later, Viola was a New York Met.

Trouble had begun brewing early in the 1989 season as Viola sought to renegotiate and extend his contract with the Twins. He and the club sparred for weeks before Viola finally accepted a three-year $7.9 million deal, matching the contract signed by the National League’s reigning Cy Young winner, Orel Hershiser.43 The bitter negotiations damaged Viola’s standing with Twins fans. He was booed while attending a circus with his family.44 Readers also sided with Twins management by a 9-1 margin in a newspaper survey about the contract standoff.45

Trouble had begun brewing early in the 1989 season as Viola sought to renegotiate and extend his contract with the Twins. He and the club sparred for weeks before Viola finally accepted a three-year $7.9 million deal, matching the contract signed by the National League’s reigning Cy Young winner, Orel Hershiser.43 The bitter negotiations damaged Viola’s standing with Twins fans. He was booed while attending a circus with his family.44 Readers also sided with Twins management by a 9-1 margin in a newspaper survey about the contract standoff.45

Viola failed to pitch up to the expectations that accompanied his mega-deal — some derisively called him “Sweet Money.”46 He went 3-7 with a 4.63 ERA through the first two months of the 1989 season. Seeing Viola’s relationships in the clubhouse turning sour, and noticing that his fastball was losing some zip, the Twins executed a trade deadline deal that sent their ace to the New York Mets for five pitchers.47 As it turned out, Viola gave the Mets one excellent season and so-so season — while the Twins got several fine years as a closer from Rick Aguilera, plus good value from Kevin Tapani.

Viola was shocked by the trade but said, “This is coming home. Now I’ll have a chance to play for the team I grew up with.”48

During the remainder of the 1989 season, Viola put up a 3.38 ERA in 12 starts, one of them a duel with Orel Hershiser in the first-ever meeting between reigning Cy Young winners. Viola prevailed in a 1-0 battle, tossing a complete game three-hit shutout on just 89 pitches.49

Viola’s performance against Hershiser was a hint of what was to come in 1990 when he delivered a 20-12 record with a 2.67 ERA and led the National League in innings pitched. He finished third on the National League Cy Young ballot and was named an All-Star for the second time.

Viola was riding high again, but during the offseason doctors discovered bone spurs in his pitching elbow. Pitching through the discomfort, Viola put up strong numbers in the first half of the 1991 season (10-5, 2.80), earning his third All-Star selection. However, his performance tailed off in the second half of the year, including a disastrous 11-start stretch during which he went 1-9 with a 6.21 ERA.50 By the end of the season his ERA had spiked to 3.97 and he ended up leading the majors in hits allowed.

A free agent after the 1991 season, Viola decided to leave New York and sign a three-year $13.9 million contract with the Boston Red Sox. He pitched solidly for Boston in 1992, putting up a 3.44 ERA in 35 starts.

The following season, a phenomenal streak of durability ended when Viola injured his ankle in early May and had to miss a start for the first time in 11 years.51 Still, he had another good year, putting up a 3.14 ERA despite elbow problems.52 After a truncated mid-September start, Viola said his elbow was “the worst it’s been this season.”53 The Red Sox decided to shut him down. Shortly thereafter, Viola underwent surgery on his elbow, a procedure that was more complicated than surgeons expected.54

Viola rehabbed in time to start the 1994 season with the Red Sox, but his comeback came to a screeching halt on May 3, 1994 when he uncorked a wild fastball, clutched his elbow, and immediately went to a hospital for X-rays.55 A few days later, a headline in the Chicago Tribune blared “Viola’s Career Could Be Over.”56 He needed elbow surgery again.

After undergoing Tommy John surgery, the once-indestructible Viola found himself reflecting on the game he couldn’t play. He said, “For the first time in my career, I realized how much I loved the game, and how much I took it for granted.”57 He was willing to do whatever it took to get back to the big leagues.

In 1995 Viola signed a minor league deal with the Toronto Blue Jays, made some appearances in the minors, and then exercised an opt-out option to sign with the Cincinnati Reds organization. Once a top-earning big league pitcher, Viola found himself making $5,000 a month toiling for the Triple-A Louisville Reds.58 Still, he found satisfaction. “This is the first time I’ve ever had to work for anything,” Viola said. “I’ve had things easy. I never was hurt. Now all of a sudden, people are writing me off. Getting to this point where I’m at right now is the best feeling I’ve ever had in baseball because I’ve had to work for it.”59

Viola was eventually called up to Cincinnati and was hit hard in three starts. The Reds let him become a free agent that November. The following year, 1996, he latched on with the Blue Jays again, going to Toronto’s spring camp as a non-roster invitee. At the end of spring training Viola accepted an assignment to Double-A Knoxville, where he had a 1.64 ERA in four starts and got his fastball up to 87 mph.60 The Blue Jays were impressed enough to call him up to Toronto.

In his return to the majors, the Cleveland Indians battered Viola for ten runs in four innings, and he continued to struggle after that. On May 28 Viola faced the Chicago White Sox in his sixth start of the season. In the middle of the game, Blue Jays star Joe Carter got hit by a pitch. Viola retaliated the next inning, drilling Chicago’s Tony Phillips with a fastball. After the ensuing bench-clearing commotion, Viola walked off the field to a rousing ovation.61

It was the last pitch he ever threw — the Blue Jays released Viola just over a week later. He wasn’t surprised — he’d been hit hard and admitted that it was embarrassing at times, yet he still saw glimmers of his old self. The day before he was released, he said, “I’ve got a lot of pride, and I’d have no problem walking away from the game. But I’ve gone through a lot just to get back to this point…and I’ve seen signs that I can still do it.” He added that ideally, he wanted to get 15 or 20 starts and then decide — but also noted, “I don’t want to hang on just to hang on.”62

In November he announced his retirement. “No offers came along and I decided it was time to go,” he said.63 After his announcement, Viola’s wife, Kathy, threw him a retirement party attended by around 200 friends and family. A visibly moved Viola said, “It’s kind of weird all of a sudden being an ex-athlete, but I’m going to enjoy it.”64

After his playing career ended, Viola spent time with Kathy and their daughters Brittany and Kaley, and their son Frank III. He also discovered a passion for coaching. He spent many years as a pitching coach in the Mets’ minor league system, including stints with the Single-A (short season) Brooklyn Cyclones (2011), the Single-A Savannah Sand Gnats (2012-2013), the Triple-A Las Vegas 51s (2014-2017), and the Double-A Binghamton Rumble Ponies (2018). In 2019 he became the pitching coach for the High Point (North Carolina) Rockers of the independent Atlantic League, which allowed him to be home with Kathy after the couple relocated from Florida to North Carolina.65

Surely many of the young players under his tutelage today have not heard of Viola. But one can imagine the instant respect he earns when they punch his name into an Internet search engine and read about his big league accomplishments, as well as the pitching artistry that earned him the “Sweet Music” moniker and a prominent place in baseball history.

Last revised: April 13, 2020

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Joe DeSantis and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Notes

1 Nick Cafarado, “V is for victory, Lefthander Viola ready to bring his winning ways to the Red Sox,” Boston Globe, January 6, 1992.

2 Anthony McCarron, “Perfect Pitch. Viola Brings ‘Sweet Music’ Back to Mets as Class A Pitching Coach,” New York Daily News, February 20, 2011.

3 Cafarado, “V is for victory.”

4 Cafarado, “V is for victory.”

5 Cafarado, “V is for victory.”

6 Bob Nightengale, “Viola’s change-up is music to Twins’ ears,” Montreal Gazette, September 6, 1988.

7 Cafarado, “V is for victory.”

8 Peter Gammons, “Near-Perfect Pitch,” Sports Illustrated, August 22, 1988.

9 SNY, Frank Viola Remembers St. John’s. July 14, 2015. Video file retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JjEudP5Zp_s. For more on Russo, see “Former St. John’s baseball coach, player Russo dies at 74,” USA Today, May 27, 2019.

10 Craig Wolff, “Players; Viola is Fulfilling His Early Promise,” New York Times, July 19, 1984.

11 Cafarado, “V is for victory.”

12 Joseph Durso, “Viola and Franco Glad to Be Home,” New York Times, April 2, 1990.

13 The Yale-St. John’s game has been written about extensively, but the classic account is Roger Angell’s “The Web Of The Game,” from the July 12, 1981 issue of The New Yorker.

14 Jim O’Connell, “Darling-Viola College Duel Remembered,” Los Angeles Times, August 6, 1989.

15 Zach Schonbrun, “Viola-Darling Pitching Duel in 1981 Has Not Been Forgotten,” New York Times, June 9, 2012.

16 Michael Martinez, “World Series; Viola’s Long Wait Was Well Worth It,” New York Times, October 18, 1987.

17 Dan Barreiro, “At long last, Viola is pitching up to Twins’ expectations,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, July 19, 1987.

18 Cafarado, “V is for victory.”

19 Wolff, “Players; Viola is Fulfilling His Early Promise.”

20 Wolff, “Players; Viola is Fulfilling His Early Promise.”

21 Jay Weiner, “Viola eager to showcase his skills in Game 1,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, October 7, 1987.

22 Barreiro, “At long last, Viola is pitching up to Twins’ expectations.”

23 Barreiro, “At long last, Viola is pitching up to Twins’ expectations.”

24 Barreiro, “At long last, Viola is pitching up to Twins’ expectations.”

25 Howard Sinker, “Time to meet expectations — Twins’ Viola has heard the plaudits; now he must produce the numbers,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, March 29, 1987.

26 Gammons, “Near-Perfect Pitch.”

27 Gammons, “Near-Perfect Pitch.”

28 Dennis Brackin, “Class of ’82: It’s time to put up or shut up,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, April 5, 1987.

29 Thomas Boswell, “Suddenly a Worldbeater, Viola Relishes the Change,” The Washington Post, July 14, 1988.

30 Patrick Reusse, “Viola seeks a new thrill as All-Star,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, July 12, 1988.

31 For more on how Podres assisted Viola with his changeup and mechanics, see Dan Barreiro, “Viola remains teacher’s pet,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, September 2, 1988.

32 Gammons, “Near-Perfect Pitch” (quoting Viola saying “I’ll throw the change anytime except the first pitch of the game. That wouldn’t look right.”)

33 Roger Angell, “Get out your handkerchiefs,” The New Yorker, December 7, 1987.

34 MLB, 1987 WS Gm4: Lawless drills clutch homer, flips bat. Video file retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OB-rdG4u_zU. Lawless’s homer was followed by an epic bat flip. Viola ran into Lawless on a golf course 20 years later and good-naturedly told him he would have knocked him down if he had faced him again. See HBC Sports, Hard Ball Conversation. Frank Viola edition. Video file retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DdmOyYG90wo. (Viola discusses his encounter with Lawless at the 1:13 mark.)

35 Mark Vancil, “World Champions! MVP Viola puts Twins in seventh heaven,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, October 26, 1987.

36 Dennis Brackin, “More sweet music: Gladden gets share of hit record,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, October 26, 1987. (The “Sweet Music” banner is now held by the Minnesota Historical Society.)

37 “Left-hander Viola bids to string along with Twins,” Toronto Globe and Mail, September 17, 1988 (noting that Viola “has control over what most scouts consider baseball’s best changeup.”) See also Steve Aschburner, “Viola vs. Puckett: A dream matchup,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, April 2, 1989 (noting that in 1988 Viola “blew hitters away with his fastball and frustrated them with his changeup,” and quoting Toronto’s Lloyd Moseby saying, “[Viola is] so confident in himself, he’s cocky. He’ll throw you any pitch at any time.”).

38 Boswell, “Suddenly a Worldbeater.”

39 Aschburner, “Viola vs. Puckett: A dream matchup.”

40 Mark Vancil, “Terrific trio all have seasons for the ages,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, October 2, 1988.

41 Nightengale, “Viola’s change-up is music to Twins’ ears.”

42 Gammons, “Near-Perfect Pitch.”

43 “Viola Wins Raise, Loses Game,” New York Times, April 20, 1989.

44 Patrick Reusse, “All those C-notes haven’t helped Viola make sweet music,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, May 31, 1988.

45 Tony Moton, “Survey: Sweet Music strikes a sour note,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, April 14, 1989.

46 Reusse, “All those C-notes.”

47 Mark Vancil, “Twins send Viola to Mets for 5 pitchers,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, August 1, 1989.

48 Vancil, “Twins send Viola to Mets for 5 pitchers,”

49 Tom Verducci, “It’s Cy AL 1, Cy NL 0 Viola defeats Hershiser in historic game,” Newsday, August 29, 1989. (During the game, Viola also picked up his first big league hit, a bloop single.)

50 Jeff Lenihan, “Sour times for ‘Sweet Music’: Viola having subpar season,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, September 15, 1991.

51 Michael Vega, “Viola’s fine effort keeps string going,” Boston Globe, July 26, 1993.

52 Vega, “Viola’s fine effort keeps string going.” A game story from mid-August reported that “[Viola’s] elbow obviously bothered him in the sixth, his final inning. You could hear him shout ‘Damn!’ a couple of times all the way up in the press box.” Joe Donnelly, “Viola Is Big Pain To Yanks,” Newsday, August 11, 1993. Missed starts due to elbow pain cost Viola an opportunity to become only the second pitcher in baseball history to make at least 34 starts in 11 straight seasons. “Baseball Briefly,” The Ottawa Citizen, August 22, 1993.

53 Nick Cafarado, “Viola gets the victory — and a stiff elbow,” Boston Globe, September 17, 1993.

54 Nick Cafarado, “Minchey pitches despite ‘minor’ heart problem,” Boston Globe, October 1, 1993.

55 Larry Whiteside, “Injury KO’s Viola; Sox win decision,” Boston Globe, May 4, 1994.

56 “Viola’s Career Could Be Over,” Chicago Tribune, May 6, 1994.

57 Larry Whiteside, “Viola embarks on road to recovery,” Boston Globe, June 1, 1994.

58 “Viola Tries To Strong-Arm His Way Back To Majors,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 2, 1995.

59 “Viola Tries To Strong-Arm His Way Back To Majors.”

60 Robert MacLeod, “Jays call on Viola to bolster rotation,” Toronto Globe and Mail, April 27, 1996.

61 Richard Griffin, “If Viola’s finished, he leaves as a hero to Jays,” Toronto Star, May 29, 1996.

62 John Harper, “Viola’s facing the music,” New York Daily News, June 7, 1996.

63 “Viola Announces Retirement,” New York Times, November 23, 1996.

64 Leslie Doolittle, “Michael Jordan Polished — On, Off Court,” Orlando Sentinel, November 24, 1996.

65 Mike Ashmore, “Patriots struggle vs. expansion Rockers,” Bridgewater Courier-News, May 1, 2019.

Full Name

Frank John Viola

Born

April 19, 1960 at Hempstead, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.