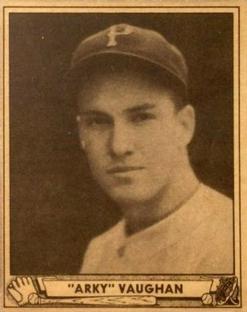

Arky Vaughan

Hall of Famer Arky Vaughan spent most of his career playing shortstop for the Pittsburgh Pirates, but was a valuable member of the Brooklyn Dodgers for his last four years in the major leagues. He played a key role as a reserve on the pennant-winning 1947 squad. Vaughan’s presence on the team in any role was unusual, to say the least. He had nearly fomented a player strike in 1943, when he became irate over manager Leo Durocher’s reprimanding a teammate in the press. He then quit the team at the end of the season and sat out three full years before returning in 1947.

Hall of Famer Arky Vaughan spent most of his career playing shortstop for the Pittsburgh Pirates, but was a valuable member of the Brooklyn Dodgers for his last four years in the major leagues. He played a key role as a reserve on the pennant-winning 1947 squad. Vaughan’s presence on the team in any role was unusual, to say the least. He had nearly fomented a player strike in 1943, when he became irate over manager Leo Durocher’s reprimanding a teammate in the press. He then quit the team at the end of the season and sat out three full years before returning in 1947.

Vaughan’s career achievements were remarkable. In 1935 Vaughan led the National League with a .385 batting average, and his .318 lifetime average is second among all shortstops to Honus Wagner’s .327. Over his career Vaughan walked 937 times, while striking out just 276 times. He was among the most difficult players to double up, grounding into only seventy double plays in the last thirteen years of his fourteen-year career. (GIDP was not tracked in 1932). Vaughan’s on-base average was an impressive .406 while his slugging percentage was a highly respectable .453. An All-Star selection for nine consecutive years, he compiled a .364 batting average in All-Star Games, and he was the first player to hit two home runs in one.

Joseph Floyd Vaughan was born on March 9, 1912, in Clifty, Arkansas, a farm village about twenty-five miles northeast of Fayetteville. When Arky was seven months old, his parents, Robert and Laura Vaughan, moved the family, including two older sisters, to Mendocino County near San Francisco. They later relocated to Fullerton, California, where Robert found work in the California oilfields. Joseph Floyd Vaughan’s childhood friends began calling him Arky as soon as they learned of his birthplace, and he was known as Arky Vaughan for the rest of his life.

At five feet ten inches and 175 pounds, Vaughan was a multisport star at Fullerton High School. In addition, he played on the undefeated Cypress Merchants of the Orange County Winter League in 1930-31. A neighbor of Vaughan’s tipped off Pirates’ scout Art Griggs about about the youngster’s abilities and Griggs signed him in January 1931.

Playing his first season of professional baseball for the 1931 Wichita Aviators of the Class A Western League, the nineteen-year-old Vaughan made an immediate impact. He batted .338 with twenty-one home runs, eighty-one runs batted in, and a league-leading 145 runs scored and forty-three stolen bases. Vaughan’s performance earned him a promotion to the Pirates.

No-hit, good-field Tommy Thevenow had been the Pirates’ regular shortstop in 1931, and manager George Gibson started him at the position in the 1932 opener. Five days later, on April 17, the twenty-year-old Vaughan made his major-league debut, striking out as a pinch-hitter against Cincinnati’s Larry Benton. Vaughan got his first start at shortstop on April 28, after Thevenow broke a finger. The left-handed hitting Californian made an impressive debut with two triples and three runs batted in. The next day, facing future Hall of Fame pitcher Eppa Rixey, Vaughan went 2-for-4. Now firmly established as the Pirates’ starting shortstop, Vaughan had a 5-for-5 day on June 7. He hit his first major-league home run on July 26, off Jim Mooney of the New York Giants.

Vaughan’s rookie batting average was .318, but he struggled in the field, committing a league-leading forty-six errors. On August 11, Vaughan the youngest player in the National League, made a crucial error in the tenth inning that allowed the Chicago Cubs to beat Pittsburgh and take over first place in the National League. The Pirates eventually finished second, four games behind the Cubs.

In 1933 Vaughan played shortstop in all but two of the Pirates’ games and began to exhibit good power as well as outstanding speed. On May 1 he and catcher Earl Grace both slugged grand slams in a rout of the Philadelphia Phillies. For Vaughan, whose home run was inside-the-park, it was the first of his four major-league grand slams. On June 24, he hit for the cycle, going 5-for-5 with five RBIs against Brooklyn.

Teammate Lloyd Waner recalled Vaughan’s speed in an interview with author Donald Honig: “For going from home plate to second base I don’t think there was anybody who could match him.” Vaughan batted an impressive .314 for the ’33 Pirates, as they again were runners-up in the National League.

After Vaughan again made forty-six errors at shortstop, the Pirates hired their legendary shortstop Honus Wagner as a coach. Wagner even roomed with his young protégé on the road. According to a Wagner biographer, Wagner wasn’t much of an instructor but his presence and guidance helped Vaughan settle down. “They said if I couldn’t make a shortstop out of Arky Vaughan, nobody could,” Wagner recalled almost two decades later. “Of all the players I tried to help, he’s the best and the one that went the farthest.”

Fifty-one games into the 1934 season, the Pirates replaced manager George Gibson with Pie Traynor. Pittsburgh slumped to fifth place, but the twenty-two-year-old Vaughan sparkled, batting an NL fourth-best .333, with a career-high forty-two doubles, eleven triples, twelve home runs, and ninety-four RBIs. He made his first appearance in the All-Star Game, played at the Polo Grounds in New York. Vaughan entered the game in the fifth inning as a pinch-hitter and remained in the game, going hitless and compiling two putouts and an assist in the field.

In 1935 Vaughan had the best season of his career. He was hitting .401 in mid-September, but an eight-game slump lowered his final batting average to .385. Arky led the league in walks (97), on-base percentage (.491) and slugging percentage (.607), and his nineteen home runs and ninety-nine runs batted in were career highs. His .491 on-base percentage remains the highest ever for a Pirates’ player. Vaughan finished third in the baseball writers vote for the National League’s Most Valuable Player; however, The Sporting News selected him as their MVP in the National League and the shortstop on their postseason Major League All-Star team.

Vaughan continued to put up impressive numbers in 1936, batting .335 with seventy-eight runs batted in. His patience and selectivity at the plate produced a career-high 118 walks, the third consecutive year he had led the NL in walks. Vaughan also topped the league in on-base percentage for the third consecutive year, and he scored a league-best 122 runs.

In 1937 Vaughan hit only five home runs, but two came in one game, against Carl Hubbell on May 13. Arky played twelve games in the outfield, but none at third base during the season. Yet he started at third base in the All-Star Game, going 2-for-5 in an NL loss at Washington.

Throughout the summer of 1938, the Pirates battled New York, Chicago, and Cincinnati for the league lead. With a week left in the season, the Pirates led Chicago by two games. Sparked by player-manager Gabby Hartnett’s fabled “Homer in the Gloamin’,” the Cubs swept a three-game series from the Pirates at Wrigley Field and won the pennant by two games over Pittsburgh. Vaughan batted .322 for a second consecutive year, and again was third in the league’s MVP race. He was selected for his fifth consecutive All-Star Game, but he did not play.

Once considered a liability defensively, Vaughan improved his fielding dramatically from 1938 through 1940. He led the NL three times in assists, twice in putouts, and once each in total chances per game and double plays. He did, however, commit a league-leading fifty-two errors in 1940.

The Pirates fell to sixth place in 1939, their final season under Pie Traynor. Vaughan batted a solid .306 and again made the All-Star team. He started at shortstop for the National League at Yankee Stadium and scored his team’s only run. A few days later, on July 19, Vaughan hit for the cycle for the second time in his career, again going 5-for-5.

In 1940, under new manager Frankie Frisch, Vaughan batted an even .300, drove in ninety-five runs, and led the National League in runs scored and triples. The 1941 season was Vaughan’s last year in Pittsburgh. Playing in only 106 games, he hit .316 with six home runs and just thirty-eight RBIs. Vaughan’s playing time was limited by two injuries. In midseason he suffered a spike wound and was out of the lineup for two weeks. Then, on August 30, he suffered a concussion when he was hit in the head by a pitch during an exhibition game in London, Ontario. Vaughan tried to return to the lineup, but he had severe headaches, and the team doctors ordered him to bed.

Despite his drop in production, Vaughan was again selected as the starting shortstop for the National League All-Star team. In the All-Star Game at Briggs Stadium in Detroit, Vaughan had perhaps his most memorable performance. After getting a single early in the contest, he homered in the seventh with a man on base, putting the National League ahead, 3–2. In the next inning, Vaughan hit his second successive two-run homer, raising the National League’s lead to 5–2. Vaughan appeared to be the day’s hero until Ted Williams of the Red Sox won the game for the American League, 7–5, with a dramatic ninth-inning, three-run homer.

On December 12, 1941 the Pirates traded their popular and perennial All-Star shortstop to the Brooklyn Dodgers for pitcher Luke Hamlin, catcher Babe Phelps, outfielder Jimmy Wasdell, and second baseman Pete Coscarart. “Many of the Pirate faithful shook their heads,” wrote Fred Lieb. “They didn’t want to see Arky get away.”

Playing mostly at third base in 1942 for the Dodgers and their fiery manager, Leo Durocher, Vaughan hit .277 as Brooklyn won 104 games, but still finished two games behind pennant-winning St. Louis. In his final All-Star Game, at the Polo Grounds, Vaughan played third base and went hitless in two at-bats.

Vaughan rebounded in 1943 with a solid performance in what turned out to be his final season as a regular player. He batted .305 and led the NL in stolen bases and runs scored. He played in ninety-nine games at shortstop and fifty-five at third base.

On July 10 of that year, manager Durocher suspended pitcher Bobo Newsom for insubordination. Dodgers second baseman Billy Herman remembered, “I was having breakfast together with Augie Galan and Arky Vaughan at the New Yorker Hotel. Vaughan was a guy who always had everybody’s respect, as a ballplayer and as a man. He never said too much, but everybody admired and respected him.” Vaughan read a newspaper interview in which Durocher made accusations against Newsom. Herman recalled that Vaughan was quiet but seemed to be upset by what he read. Later, at the ballpark, Vaughan angrily confronted Durocher, who confirmed that he had given the interview. Herman recalled, “Arky didn’t say another word. He went back to his locker and took off his uniform—pants, blouse, socks, cap—made a big bundle out of it, and went back to (Durocher’s) office.

“Take this uniform,” he said, “and shove it right up your ass.” And he threw it in Durocher’s face. “If you would lie about Bobo,“ he said, “you would lie about me and everybody else. I’m not playing for you.”

Most of his teammates sided with Vaughan and decided not to play that afternoon against Pittsburgh. Durocher, with help from general manager Branch Rickey, eventually persuaded all the Dodgers—except Vaughan—to play. Arky and Newsom watched the start of the game in street clothes from the right field stands. Rickey asked Vaughan to return to the team, and he did. Arky was back on the bench in uniform before the end of the game.

At season’s end, possibly still upset with Durocher, Vaughan decided to put his baseball career behind him. He returned to his Northern California cattle ranch with his wife, Margaret, his former high school sweetheart, whom he had married in 1931, and their four children. Vaughan remained in retirement until 1947, when Rickey coaxed him back to the Dodgers.

At the age of thirty-five, after missing three full seasons, Vaughan managed to hit .325 as a part-time player. The season was marked by the one-year suspension of Durocher and the historic debut of Jackie Robinson. Vaughan served as a respected, calming clubhouse influence for the Dodgers and Robinson that season. After Vaughan’s death, Robinson remembered, “He was one of the fellows who went out of his way to be nice to me when I came in here as a rookie. Believe me, I needed it. He was a fine fellow.”

The Dodgers won the National League pennant in 1947, and Vaughan had an opportunity to play in his only World Series. Facing the Yankees, Vaughan drew a walk and belted a double in three pinch-hitting appearances. Vaughan returned to the Dodgers in 1948 as a part-time player, but by 1949, wanting to be closer to home, he joined the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League. In his final season of professional baseball, Arky batted .288 in ninety-seven games.

Following his retirement from baseball, Vaughan devoted all his energies to his family, his ranch, and his hobby of fishing. On August 30, 1952, he and a friend, Bill Wimer, sailed their fishing boat to Lost Lake, east of the Northern California town of Eagleville. The lake, in the crater of an extinct volcano, had reportedly never been sounded. The skiff capsized and, according to a witness, Vaughan and Wimer started swimming for shore. The men swam about sixty-five yards in the chilly water and were only twenty feet from shore when they sank in water that was twenty feet deep. Later reports stated that Vaughan was trying to save Wimer, who, it was reported, could not swim. Their bodies were recovered early the next morning. Vaughan was forty years old.

The baseball world mourned his passing. Pee Wee Reese called Vaughan “a steady, easy-going guy, and (he) had a good long life to look forward to.” Cookie Lavagetto said, “I never knew a finer fellow or a better team man.” Charlie Dressen said, “I knew him for many, many years. He was a great team man.” National League president Warren Giles said, “The whole sporting world lost a gentleman and a fine competitor in the death of Arky Vaughan. He contributed much to National League prestige in the fourteen years he played with the Pirates and Dodgers. I am deeply sorry to hear of his tragic death.”

Ignoring his accomplishments, the Baseball Writers’ Association of America never gave Vaughan more than 29 percent of their votes for the Baseball Hall of Fame. (75 percent is required for election.) Vaughan dropped off the BBWAA ballot after 1968, and not until 1985 did he at last gain election, by a vote of the Veterans’ Committee.

Yet Arky Vaughan remains relatively unknown in comparison to his fellow Hall of Famers. Overlooked and underappreciated, Vaughan ranks among the top shortstops and offensive stars of his or any era.

Sources

Fleitz, David. More Ghosts in the Gallery. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Publishing Co., 2007.

Hageman, William. Honus: The Life and Times of a Baseball Hero. Champaign, Illinois: Sagamore Publishing, 1996..

Honig, Donald. Baseball When the Grass Was Real. New York: Coward, McCann and Geoghegan, 1975.

Honig, Donald. The October Heroes. New York: Simon and Shuster. 1979.

McConnell, Bob, and David Vincent, eds. “SABR Presents the Home Run Encyclopedia.” New York: Macmillan, 1996.

Reichler, Joseph L. The Great All-Time Baseball Record Book.” New York: Macmillan, 1981; revised by Ken Samelson, 1993.

The Baseball Dope Book.” St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1981.

Richard “Dixie” Tourangeau, “Play Ball 1995,” calendar published by Tide-Mark Press.

Full Name

Joseph Floyd Vaughan

Born

March 9, 1912 at Clifty, AR (USA)

Died

August 30, 1952 at Eagleville, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.