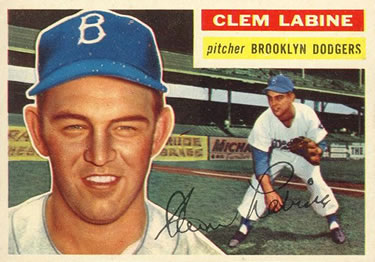

Clem Labine

One of the most important games hurled by Clement Walter Labine took place at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn on October 9, 1956. The day before, Don Larsen had pitched a perfect game for the New York Yankees to beat the Brooklyn Dodgers, 2-0, in the fifth game of the World Series.

One of the most important games hurled by Clement Walter Labine took place at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn on October 9, 1956. The day before, Don Larsen had pitched a perfect game for the New York Yankees to beat the Brooklyn Dodgers, 2-0, in the fifth game of the World Series.

Dodgers manager Walter Alston gave the ball to the right-handed Labine, who was usually a reliever, because he knew about Clem’s courageous and smart demeanor once he got on the mound. With the Yankees up three games to two, manager Casey Stengel sent starter Bob Turley to try to win the Series. Labine and Turley battled in a scoreless game until the bottom of the tenth, when Jackie Robinson’s single drove in Jim Gilliam to tie the Series at three games apiece and break a streak of 18 scoreless innings for the Dodgers.

Labine played in five World Series – four with the Dodgers (1953, 1955, 1956, 1959) and one with the Pirates (1960). Three of his teams were winners: the 1955 Brooklyn Dodgers, the 1959 Los Angeles Dodgers, and the 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates.

Clement Walter Labine was born on August 6, 1926, in Lincoln, Rhode Island, and grew up in nearby Woonsocket, where he played football, hockey, and baseball. His parents were French-Canadian. The father was a weaver and the mother was in charge of the family.

At Woonsocket High School right-hander Labine was said to have had a curve like a left-hander. That was his pitch. As a youngster he had broken his right index finger. He thought his baseball dreams as a player were over, but his coach told him that some things that appear to be disasters turn out to be blessings in disguise. That became the greatest advice Labine got, because it shaped his attitude to the game and life. Clem met the most important person in his life; he met the power inside of him that would destine him for greatness.

In 1944, after high school, Labine was signed by Branch Rickey and Chuck Dressen of the Dodgers. Labine had a tryout scheduled with the Boston Braves, but it fell through, and he was still available when Rickey and Dressen met him. Still only 17 years old, he was assigned to the Newport News Dodgers of the Piedmont League (Class B) and appeared in 12 games (2-4, in 56 innings of work with a 4.18 earned-run average). World War II was on and soon after Labine turned 18 in August, he volunteered for the paratroopers. He was out of baseball all of 1945 and, after his discharge from the Army, returned to Newport News late in the 1946 season. His only decision was a win, and he allowed four earned runs in 14 innings for a 2.57 ERA in his brief time with the team.

In 1947 Labine, now 20 years old, pitched for three teams, Newport News, the Asheville Tourists (Class B Tri-State League), and the Greenville Spinners, of the Class A South Atlantic League. He pitched exceptionally well for Asheville (6-0, 2.07 ERA), but poorly for the other two teams (one victory, four defeats). He spent the following year, 1948, entirely in Class A, playing in Colorado for the Western League’s Pueblo Dodgers (13-10, 4.32 ERA).

Labine’s last full year in the minors was 1949 with the Triple-A St. Paul Saints. He was 12-6 with a 3.50 ERA, and he made the Brooklyn Dodgers out of spring training in 1950, debuting on April 18 and pitching the final two innings of a 9-1 loss to the Philadelphia Phillies allowing one run. That was his first, albeit brief, taste of the majors. He was then sent back to St. Paul, where he won 11 and lost 7, with a less successful 4.99 ERA.

After the 1950 season Labine went to play winter ball in the Venezuelan League, for the Magallanes Navigators. In 24 games he was 13-4 with 93 strikeouts and an ERA of 1.95, beating rival Cerveceria Caracas eight times. Caracas fans called him “La Vaina,” a derogatory term (which means he was considered annoying, like Bugs Bunny) that sounded like Labine, because of how difficult it was for their team to defeat him. Labine was a key player for that championship Magallanes team.

Labine tried hurling spitters in Caracas once. Someone explained to him how to throw the spitball, which was illegal in Venezuelan baseball, and which pitchers threw at risk of being fined or suspended if they were caught. But the first time he threw it he hit the catcher in the throat and he stopped using the pitch because he couldn’t control it. Labine also developed a sinkerball and threw an unorthodox curveball, called a “cunny thumb” curve. It’s thrown by holding the thumb parallel to the index and middle fingers, as opposed to the common method of placing the thumb on the opposite side of the ball. To remind himself to turn his non-pitching hand over his pitching hand to better hide the ball from the batter, Labine printed the letters “T-U-R-N” on the four fingers of his glove.

In 1951, after going 9-6 for the Saints, with a 2.62 ERA, Labine was called up to Brooklyn and racked up five wins against just one loss, with two shutouts (the only regular-season shutouts of his major-league career). He then found himself thrust into the middle of the best-of-three National League pennant playoff between the Dodgers and the New York Giants. After the Giants won the opener, Brooklyn had no regular starter available for Game Two. Labine got the assignment by default and threw a six-hit shutout to keep the Dodgers alive in the series. The Dodgers won 10-0. In the third inning, when it was a 2-0 game, the Giants’ Bobby Thomson came to bat with the bases loaded. Thomson had doubled in his previous at-bat. With a 3-and-2 count, Labine threw his curve. It broke a foot wide of the strike zone, but Thomson swung and Labine got a strikeout. The next day Thomson’s ninth-inning home run won the pennant for the Giants. Labine was in the bullpen with Carl Erskine and Ralph Branca. When the ball went out of the park, Labine and Erskine both bit the wooden bench where they sat. Labine later said: “I broke down a little, but I learned a lot about losing.”

The 1952 season was up and down for Labine. He was briefly with St. Paul (0-1). With the Dodgers he was 8-4 with an earned-run average of 5.14.As a reliever he was 6-1, with a 3.54 ERA. He gave up 47 walks in 77 innings. In 1953 he turned it around and he became the Dodgers’ bullpen ace thanks to the mastery of the sinkerball he had developed in Venezuela.

Labine’s sinker forced batters to pound the ball into the ground. “They go to swing at it, and it drops on you, and you get the top of the ball,” he told Peter Golenbock in Bums, an oral history of the Brooklyn Dodgers. “So you’re not gonna hit a lot of line drives off of me, just a lot of groundballs. And don’t forget who we had scooping them up: Gilly (Gil Hodges), (Jackie) Robinson, (Pee Wee) Reese, and (Billy) Cox.” 1

In 1953 Labine pitched in 37 games, with 11 wins and six losses, a 2.77 ERA, and seven saves in 110? innings of work. In the World Series, against the Yankees, he lost two games in relief and saved one. Labine lost the first game, 9-5, giving up a tiebreaking home run to first baseman Joe Collins. He saved the fourth game for Billy Loes, coming in with the bases loaded and nobody out in the ninth inning. He got two quick outs, then gave up a hit to Mickey Mantle, allowing Gene Woodling to score. But Billy Martin was out trying to score behind Woodling with the Yankees still down by four, and the game was over. Labine lost the deciding Game Six in relief. He entered the game in the seventh inning with the Dodgers down 3-1 and held the Yankees scoreless in the seventh and eighth. After his teammates tied the game with two runs in the top of the ninth, Labine walked Hank Bauer, then gave up a single to Mantle and a solid grounder up the middle by Billy Martin that won the Series for the Yankees. In three games and five innings of work, Labine was 0-2, with a 3.60 ERA but he had protected the only lead he was given.

In 1954 Labine was 7-6, 4.15 ERA and five saves. In 1955, as the Dodgers won the pennant and the World Series, he appeared in a league-leading 60 games, eight of them starts, and compiled a 13-5 record, with 11 saves, and a 3.24 ERA in 144? innings.

Clem was never much of a batter. In his 13 major-league seasons he had only 17 hits and a batting average of .075. In 1955 he had three hits and a .097 batting average. But all three hits were home runs – and they were the only three he ever hit in the major leagues. (He hit three in the minors.)

Labine appeared in four games in the 1955 World Series, winning one and saving one with 2.89 ERA. On back-to-back days, in Games Four and Five, he got a win and a save. In Game Four he pitched 4? innings, retiring 11 of the final 12 batters, and got the victory as the Dodgers came from behind to top the Yankees, 8-5, and tie the Series at two victories apiece. In Game Five Labine pitched three innings in relief of Roger Craig, allowing a homer by Yogi Berra but inducing two double plays to preserve the 4-3 Dodgers win. The Dodgers won the Series in Game Seven on Johnny Podres’ shutout.

Although save totals were not kept in that era, retroactively Labine was credited with leading the National League with 19 saves in 1956 and 17 in 1957. He led the league in games finished (47) in 1956 and rolled up a 10-6 record. In 1957 he was 5-7. He also was fourth (1956) and third (1957) in games pitched.

“Clem Labine was one of the main reasons the Dodgers won it all in 1955,” said Dodgers announcer Vin Scully. “He had the heart of a lion and the intelligence of a wily fox … and he was a nice guy, too.” 2

In 1958 the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles. There Labine posted a 6-6 record with a 4.15 ERA and 14 saves in 104 innings. The next season, though he finished 5-10 with nine saves, he broke Brickyard Kennedy’s franchise record of 382 games pitched from the turn of the century. That season the Dodgers reached the World Series after defeating the Milwaukee Braves in a postseason playoff. They defeated the Chicago White Sox in six games in the World Series, with Labine’s only appearance a one-inning stint in one of the Dodgers’ two defeats.

Over the years Labine started 38 games all but one for the Dodgers. Fellow Dodgers pitcher Carl Erskine said he thought the reliever “would have had a great career” as a starter. But Erskine said Labine told him, ‘I didn’t want to start. I liked the pressure of coming into the game with everything on the line.’” 3

In 1960, after he had pitched just 17 innings in the first two months of the season, probably because manager Walt Alston had lost confidence in him after two mediocre seasons, Labine was traded to the Detroit Tigers for right-handed pitcher Ray Semproch and cash. Labine later said he missed the camaraderie and friendship he had with his Dodgers teammates. For the first few weeks, he said, he felt like an orphan in a different country. Then the Tigers released him on August 15. The next day Labine signed with Pittsburgh, won three games, saved three, and went to the World Series with the Pirates. He pitched in three games in relief against the Yankees and was hit hard, giving up 13 hits and 11 runs (6 earned) in four innings. (That was the Series in which the Yankees outscored the Pirates 55 runs to 27, but lost the Series in Game Seven on Bill Mazeroski’s walk-off home run.)

In 1960, after he had pitched just 17 innings in the first two months of the season, probably because manager Walt Alston had lost confidence in him after two mediocre seasons, Labine was traded to the Detroit Tigers for right-handed pitcher Ray Semproch and cash. Labine later said he missed the camaraderie and friendship he had with his Dodgers teammates. For the first few weeks, he said, he felt like an orphan in a different country. Then the Tigers released him on August 15. The next day Labine signed with Pittsburgh, won three games, saved three, and went to the World Series with the Pirates. He pitched in three games in relief against the Yankees and was hit hard, giving up 13 hits and 11 runs (6 earned) in four innings. (That was the Series in which the Yankees outscored the Pirates 55 runs to 27, but lost the Series in Game Seven on Bill Mazeroski’s walk-off home run.)

In the 1961 season Labine returned to the Pirates, pitched in 56 games, and went 4-1, with a 3.69 ERA, and eight saves. He was released by the Pirates after the season and caught on with the brand-new New York Mets. He pitched in only three games for the Mets (0-0, 11.25 ERA) and was released on May 1, after which he retired as a player.

Labine settled again in the Woonsocket area, where he became a designer of men’s athletic wear, serving as general manager for the sporting goods division of the Jacob Finklestein’s & Sons manufacturing company.

In 1966 Labine’s Dodger career records of 425 games pitched and 83 saves were broken by Don Drysdale and Ron Perranoski respectively but he will remain holding the Brooklyn records.

Labine had some heartbreak off the mound. While interviewing him for his book The Boys of Summer, Roger Kahn noticed that Clem drank several martinis. “You heard about Jay?” Labine said. “Who’s Jay?” “My son Clement Walter Labine Junior. He stepped on a mine in Vietnam and blew his leg off. The Marines sent a car to our house. Barbara was away. I was out playing golf. My brother-in-law saw this Marine car and went over and said, ‘Is this about Jay, Clem Labine, Jr.?’ The Marine officer was very polite. He asked who was he talking to and my brother-in-law said he was Jay’s uncle and the Marine said that under the rules he couldn’t say anything. Next of kin only. So when they came and got me off the golf course, the first thing they said was, ‘Jay’s been hurt, but he’s alive’. He wrote me a letter from the hospital. It was so calm and matter-of-fact.” Kahn wrote that this was the second time since the 1953 World Series that he had seen Labine’s eyes full of tears. “If I hadn’t been a ballplayer, I wouldn’t have been away all the time. But the traveling cost me all of it, Jay growing up. If I hadn’t been a ballplayer, I could have developed a real relationship with my son. The years, the headlines, the victories, they’re not worth what they cost us. Jay’s leg.”

But on the field, Labine was a master. “If you had a lead, there was this thing where about the seventh or eighth inning, where he’d get up, sort of a ritual, and walk down to the bullpen,” the former Dodgers pitcher Roger Craig told Bob Cairns in Pen Men, an oral history of relief pitching. “Clem was kind of a cocky, arrogant type, which was good. I liked it. He’d fold his glove up and put it in his pocket. I can see him now, strutting down to the bullpen and the fans cheering.”

Labine had, in the words of his former Brooklyn Dodgers teammate Ralph Branca, “the right equipment to be a reliever.” His sinker induced many a double play, and he possessed a sharp overhand curve that he could throw to righties and lefties. But that’s not what made Labine one of the game’s first great closers. “He also had courage,” says Branca of Labine. “He really welcomed the challenge of being a reliever. He was a tough bird who loved to be in a crucial spot.” 4

Labine died on March 2, 2007, in Vero Beach, Florida, after suffering two strokes while hospitalized with pneumonia and subsequent brain surgery.

This biography is included in the book “Sweet ’60: The 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates (SABR, 2013), edited by Clifton Blue Parker and Bill Nowlin.” For more information or to purchase the book in e-book or paperback form, click here.

Sources

Bob Cairns. Pen Men. (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1993).

Peter Golenbock. Bums: An Oral History of the Brooklyn Dodgers. (New York: McGraw-Hill/Contemporary, 2000).

Daniel Gutierrez and Efraim Álvarez. La Enciclopedia del Béisbol en Venezuela. Tomo II. (Caracas: Fondo Editorial Cárdenas Lares, 1997).

Roger Kahn. The Boys of Summer. (New York: Harper & Row, 1971).

Robert Creamer. “They even sing songs in praise of the ruler of the Dodger bullpen.” SportsIllustrated.CNN.com, Volume 6. Issue 22, June 3, 1957.

“Clem Labine, All-Star Reliever for Brooklyn Dodgers, Is Dead at 80,” New York Times, March 2, 2007.

Ken Gurnick. “Dodgers pitcher Labine dies at 80. Righty was integral member of Brooklyn’s first Series win” MLB.com, March 3, 2007.

“Dodgers’ Labine dead at 80; relief pitcher loved pressure.” Thefreelibrary.com

Notes

1 “Clem Labine, All-Star Reliever for Brooklyn Dodgers, Is Dead at 80.” New York Times, March 2, 2007.

2 MLB.com, accessed on March 21, 2008

3 MLB.com, op. cit.

4 Sports Illustrated, op.cit.

Full Name

Clement Walter Labine

Born

August 6, 1926 at Lincoln, RI (USA)

Died

March 2, 2007 at Vero Beach, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.