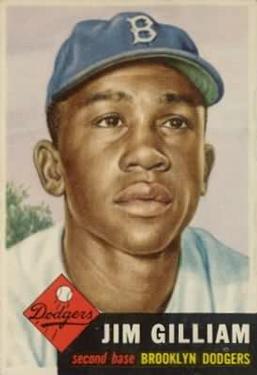

Jim Gilliam

Jim Gilliam’s career was marked by a relentless, intelligent approach to the game and an extraordinary versatility. Although he was not a perennial All-Star or Hall of Fame candidate, his exceptional attributes can’t help but intrigue a thinking baseball fan.

Jim Gilliam’s career was marked by a relentless, intelligent approach to the game and an extraordinary versatility. Although he was not a perennial All-Star or Hall of Fame candidate, his exceptional attributes can’t help but intrigue a thinking baseball fan.

He went about his business in a studious way, a craftsman who never stopped refining his skills and knowledge, accepting every new assignment with a determination to succeed. He was soft-spoken and didn’t angle for attention, though he seemed to enjoy recognition when he got it. When he didn’t get recognition or respect, he rarely showed disappointment, playing like the good soldier, doing whatever duty he was assigned.

Even with his lack of notoriety, Gilliam’s combination of remarkable achievements and unusual contradictions make him virtually one-of-a-kind:

- Almost every year, the press reported Gilliam was trade bait, but at the end of his career, he had spent his entire 14-season major league playing career with the Dodgers in Brooklyn & Los Angeles.

- Gilliam started every season after his second one not being the leading candidate for any starting position, but for the 12 seasons until he became a player-coach, he averaged 146 games played.

- “Junior” was reputed to be an ordinary defender, but the defense-driven Dodgers used him at every position in the field except for pitcher, shortstop and catcher, and his glove is on display at Cooperstown1.

- He was known for not having home run power, but hit two World Series taters in his rookie year.

- His scouting reports described him as having the highly unusual combination of a weak infield arm and a strong outfield arm.

- He was considered a dangerous base-stealer by opponents, but while he never led the league in steals, he once led the league in caught stealing. And overall, he had merely an ordinary success rate.

- Finally, in an environment where the assignment of nicknames is usually directly proportional to the charisma of the individual, Gilliam collected more nicknames than some team rosters combined despite being low-key with the press most of his career and maintaining a self-contained personality on the field.

Gilliam endured because his managers and teammates appreciated him for his versatility and relentless focus on doing the things he and they thought gave the team the best chances for winning. At the same time, his reticence to promote himself resulted in a great baseball disappointment he would take to his grave.

James William Gilliam was born on October 17, 1928, in Nashville, Tennessee. He was an only child, and when Gilliam was two, his father died. His mother had to work as a housekeeper, so his grandmother raised him.

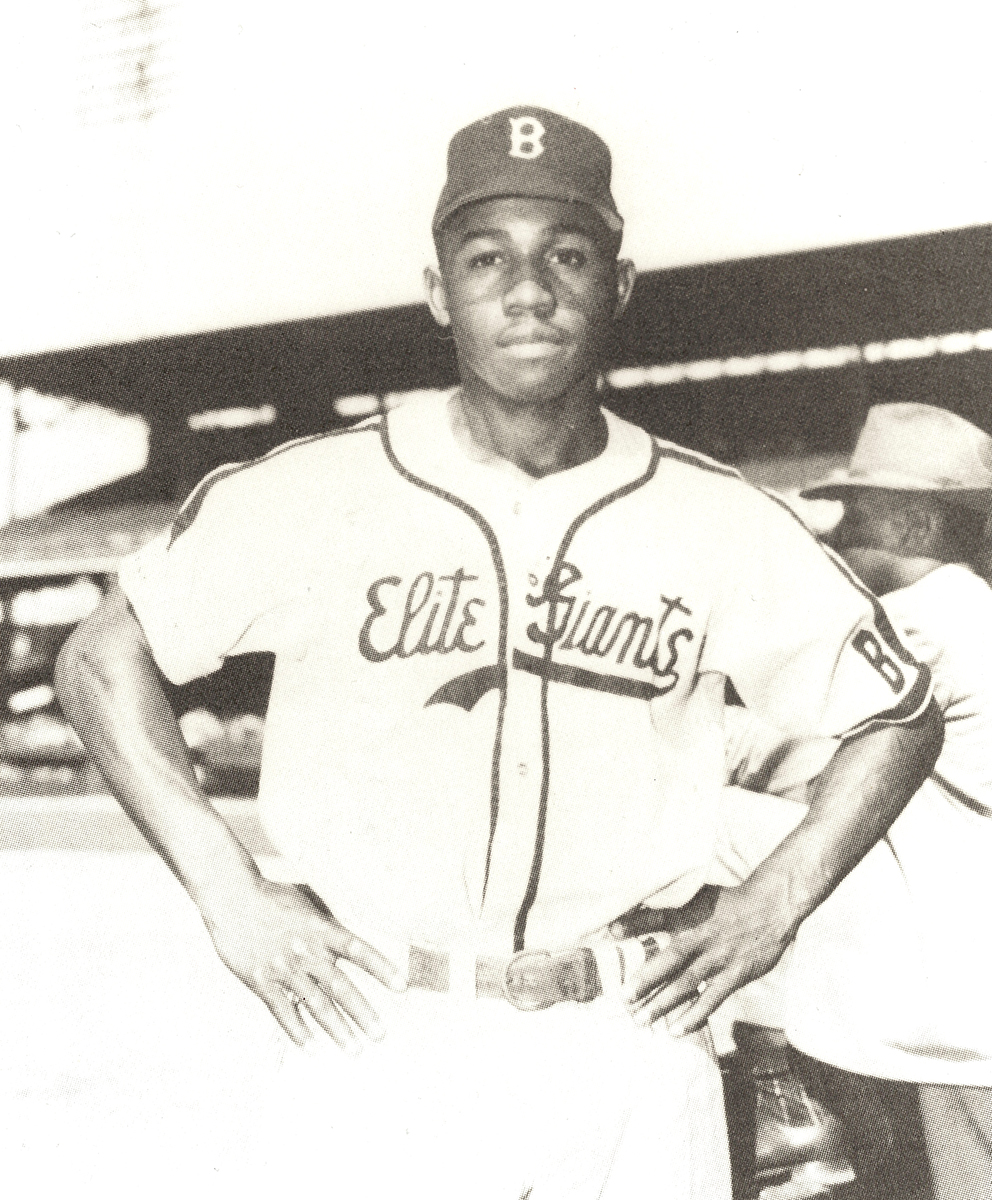

The young man started his work career early. As a high-schooler a local five-and-dime store employed him as a “porter” to help people get their goods home.2 But his love was baseball; he had the advantage of living near Nashville’s pre-eminent baseball field, Sulphur Dell, home of the Double-A Southern Association’s Nashville Vols, and in the major leagues he enjoyed following his favorite player, Joe DiMaggio. When Jim was 14 years old, his mother bought him his first baseball glove. Two years later, in 1944, he used that leather when he was paid to play for the Crawfords, a local baseball team. The next year the team’s owner Paul Jones fielded a team in a league subordinate to the Negro Leagues called the Nashville Black Vols. In 1946, the Black Vols’ parent club, the Baltimore Elite Giants of the Negro National League, brought up the 17-year old as a right-handed batting reserve infielder3. It was his tryout for the big club that made him into a switch-hitter.

When Baltimore manager George “Tubby” Scales observed Gilliam having trouble hitting curveballs thrown by right-handed pitchers, Scales yelled, “Hey, Junior, get over on the other side of the plate.”4 Scales had been a right-handed hitter in his 24 seasons of professional baseball, and prided himself on his scientific approach to the game. While the move to switch-hitting undermined what little power the prospect had, batting left-handed against righties enabled him to make good contact, and, two steps closer on a dash to first base, he could better apply his noteworthy speed. Further, Scales’ nickname for him stuck: While “Junior” was his best-known nickname, it was only one of many he would have spackled to him by teammates and scribes over the next two decades.

Teammates, particularly shortstop Pee Wee Butts, later reported Gilliam was very determined, learned quickly and was patient and selective at the plate, all traits he would carry into his major league career. One of the challenges of his promotion was that he was being slotted to replace Sammy T. Hughes. Even though the 36-year-old Hughes had returned from military service unable to play his best5, he was still a highly esteemed player.

Gilliam hit .253 in his first season with Baltimore and built on that to hit .302 in 1949.6 From 1948 to 1950, Gilliam was selected to play for the East squad in the Negro Leagues’ all-star contests, the East-West Games. In the winters of 1948-49, 1950-51 and 1952-53, the infielder played in the Puerto Rican Professional Baseball League.7, 8

Harry Postove, a scout for the Chicago Cubs in the Washington-Baltimore area, scouted the players on the Elite Giants. He watched Gilliam in 1949 and 1950 and recommended Junior’s immediate purchase. His report stated the player was “the best young prospect in the Negro American League.”9 His scouting report advised Gilliam was “a clean-cut youngster with an accurate, snap throw, a good eye, a hustler with the knack for punching the ball to all fields.”

After the 1949 season,10 Baltimore sent Gilliam to the Cubs’ AAA team in Springfield, Massachusetts, in a conditional deal: $5,000 down and a bonus if he made the team. He didn’t impress the Cubs, who sent him down to their Des Moines Class A league farm club, where he still failed to impress.11

Postove gave a reason for the demotion. The Cubs had a second base prospect, Red Hollis, who was on fire. Pitcher (and teammate) Joe Black related a different reason in his memoir.12 He said Jim had never played integrated ball before and was socially shy and uncomfortable. In Black’s version, the Cubs returned him with a note saying they were doing the 21-year-old more harm than good by trying to build his baseball skills in that environment. Yet a third explanation came from Cubs’ farm director Jack Sheehan, who said the infielder would not have been able to hit AAA pitching.13

Back in Baltimore, Jim hit .265 for the Elite Giants in 1950.

After 1950, the Brooklyn Dodgers were looking for a second baseman for the Montréal Royals, their AAA farm team. At a strategy meeting, Mickey McConnell, an assistant to Brooklyn’s general manager Buzzie Bavasi, tossed Gilliam’s name into the pile. McConnell touted Gilliam’s speed, bat control and range at second base, and he sold the Dodgers on the idea that it was worth trying.14 The Dodgers spent $9,000 to buy the contracts for three Elite Giants: Gilliam, Black and pitcher Leroy Ferrell.15

After 1950, the Brooklyn Dodgers were looking for a second baseman for the Montréal Royals, their AAA farm team. At a strategy meeting, Mickey McConnell, an assistant to Brooklyn’s general manager Buzzie Bavasi, tossed Gilliam’s name into the pile. McConnell touted Gilliam’s speed, bat control and range at second base, and he sold the Dodgers on the idea that it was worth trying.14 The Dodgers spent $9,000 to buy the contracts for three Elite Giants: Gilliam, Black and pitcher Leroy Ferrell.15

Gilliam opened the 1951 season as the starting second baseman for Montréal with Black as his roommate. If the social discomfort Black described had been Gilliam’s impediment with the Cubs, having a friend as a roommate might have helped him make the transition to integrated baseball more smoothly.

Gilliam’s play made a quick impression on fans. In an early season doubleheader, he had 11 plate appearances. He got on base all 11 times, with three walks and eight hits, one a grand-slam home run. He finished the season with a .278 batting average and 73 RBI.

In 1952, at age 23, Gilliam had his most award-filled year as a pro. Playing for Montréal, he won the International League’s MVP award by a wide margin, hitting .303, leading the league with 133 runs scored and 41 doubles, and collecting 109 RBI. His plate discipline held solid at this higher level of competition: Gilliam drew 100 walks and whiffed only 18 times.

The Brooklyn parent club that year had also captured awards. The 1952 team had won the pennant with a 96-57 record. With glove wizard Billy Cox at third base, Pee Wee Reese at shortstop, Jackie Robinson at second base, and the best-hitting utility infielder in the National League, Bobby Morgan, the team had an established infield that had gotten them to the World Series, though they finished the campaign with another Series loss to the New York Yankees.

For most management teams, a shining infield prospect in AAA who had little left to prove, and a fully stocked infield would have been a “problem.” It was not, however, cause for the Dodgers to hesitate.

The front office wanted to strengthen the team. For Bavasi and manager Chuck Dressen, that meant incorporating a real leadoff hitter. The team’s best on-base and running threat was Jackie Robinson, but the team needed his power in the No. 3 or 4 slot. Further, the team’s 1952 lineup had featured only one left-handed hitter, center fielder Duke Snider. With a line-up that featured seven or eight right-handed batters, the Dodgers had only seen lefties in 16% of their plate appearances, as opposed to the 1952 league average of 27%,16 and that undermined most of their right-handed hitters.

Still, to most people, even Dodger ace Carl Erskine, making a change seemed odd.

“Dressen was a really good manager; he could over-manage some times, but how he liked to try things. Why tinker with that team, I thought? It was so good,” Erskine remembered thinking17.

When you fix something that isn’t broken, controversy of some sort will erupt. So when Robinson moved to third base to put less daily wear and tear on bad knee,18 Gilliam was installed at second base and Cox was the odd man out. Cox was not, technically, a problem. But he had proved in 1952 that he could not bat first any better than the other batters Dressen had lead off.

There was drama around Cox being moved aside to make room for Gilliam. The 33-year-old had many fans and teammates who were friends. In addition, the racial politics of the time left a residue of “concern” over the possibility of five “Negroes” out of nine players taking the field (on the days when Don Newcombe took the mound).

Gilliam made management’s fix-it-when-it’s-not-broken gamble work.

The Dodgers won the pennant again in 1953, finishing with a record of 105-49, 8½ games better than the previous year and 13 games ahead of second-place Milwaukee. Gilliam was a major contributor.

Any question about Gilliam’s ability to improve the Dodgers’ on-base percentage (OBP) at the lead-off slot was answered quickly. He started and batted lead-off in Brooklyn’s first 24 games and got on base in all of them, slapping the ball and taking walks, squeezing out a .456 OBP and scoring 19 runs. He also had a 39-game on-base-while-starting streak from July 5 through August 26. By the end of the 1953 season, he had started 146 games, been on base in 130 of them, and scored 125 runs on a foundation of .278 batting average (BA) .383 OBP and .415 slugging percentage (SLG).

He was in the leaders’ table for a few categories, as well. He led the league in triples (17) and plate appearances (710). His 100 walks broke the league’s rookie record set by Eddie Stanky, and it tied him with Ralph Kiner for second behind Stan Musial’s National League (NL)-leading 105. He had only one negative statistic. He was caught stealing 40% of the time, having been thrown out in 14 (most in the NL) of his 35 attempts.

Billy Cox, presumptive odd-man-out, got into 89 games at third base and had his best offensive season.

In the World Series, Gilliam increased his renown with a pair of home runs.

After the season, the Baseball Writers’ Association named Jim Gilliam the NL Rookie of the Year. The Dodger captured 11 of the 24 first-place votes, lapping runner-up Harvey Haddix and also-rans Jabbo Jablonski, Rip Repulski and Bill Bruton.19

That would be the last official superlative Gilliam would receive.

While it would be a long time before Gilliam repeated the offensive excellence of 1953, his skills grew – as did his utility to the Dodgers.

During the off-season, Gilliam told a New York Times interviewer, “I think I’ll be a little better next year. I know the pitchers and how they pitch to me.”20 In 1954, however, he experienced a small sophomore slump. Most of his rate and counting stats dipped a little. He still scored over 100 runs, was again durable, playing in 146 games, and finished the season with .282 BA, .361 OBP and .418 SLG. His 13 home runs would be his career high. His old manager at Montréal, Walter Alston, started his long tenure as skipper, and Alston had been an enthusiast for using Gilliam at multiple positions.

The 1955 season showed sharper offensive declines, although he again scored over 100 runs. Newspaper stories suggested his year-round play (consistently being in the Dodger lineup during the season, plus winter ball in Puerto Rico) was taking a toll on him. Alston was also using him in the outfield more, and that required him to train and practice more at the added position.

In the 1955 World Series, the one the Dodgers finally won from the Yankees, Gilliam was an offensive contributor. He had a .469 OBP (eight walks and seven hits in 32 plate appearances). But he may best be remembered as a footnote in the critical seventh game. Facing Yankee southpaw Tommy Byrne, Gilliam was playing left field, as he had in 40 regular season games, Backup third baseman Don Zimmer was at second base. With starter Johnny Podres breezing, the Dodgers took a 2-0 lead into the bottom of the sixth inning. Alston lifted Zimmer, moved Gilliam to second and inserted left-handed speedster Sandy Amoros into left field, angling to boost his defense at two positions.

The move paid off immediately, as Amoros, playing well towards center field against the pull-hitting lefty Yogi Berra, ranged all the way to the left-field foul line to make a catch that the baserunner on first reckoned impossible. Amoros spun and hit Reese at cut-off, and they doubled-off the runner to snuff out a would-be rally. At the time, Amoros’s catch was considered one of the greatest World Series defensive gems of all time. Gilliam graciously told off-season confabulations: “I’m glad I wasn’t out there when Berra hit that ball.” He suggested that Amoros’s left-handed throwing arm/glove on his right hand afforded Sandy a couple of feet of advantage, and intimated that Amoros was faster than he was, too.21

Gilliam continued to work off-seasons for a beer distributor, but stopped playing winter ball. As his career moved on, his declining performance did, however, give the Dodger front office pause about his future. Although his mentor Alston appreciated Gilliam’s versatility and on-field smarts, the front office saw a Dodgers’ farm system packed with prospects.

So, starting in 1956, a regular story would attend every Dodger spring training through the rest of Gillam’s active career. He would go into March a possible odd-man-out, battling a phenom who was going to take his job. In 1956, it was Charlie Neal. Neal was going to replace Gilliam at second base, but Neal wasn’t as polished with the glove, and the promise of his bat did not pan out. Gilliam’s calm, workmanlike approach served him well; every year he survived, sometimes moving to a new position, and every year, played as much as anyone. Each time it was someone different: Zimmer, Neal, Jim Baxes, Johnny Werhas, Ken McMullen, Nate Oliver.

This may have been Gilliam’s natural way, or it may have been a result of his relationship with Alston, who believed strongly in Gilliam’s reliability, versatility, and durability. Further, the two were social friends. Alston was reputed to be the best pool player in baseball, and, at least when Leo Durocher served on Alston’s coaching staff, the three formed a cabal of the three toughest “sharks” in the majors.22

Even as Gilliam’s offensive numbers sagged below league average, Alston stuck with his pool buddy. Dodger teammate Ron Fairly described Alston’s comfort with Gilliam being based on field intelligence.

“He never missed a sign; all the years he played for Alston, Walt would say the one player who never missed a sign was Jim Gilliam,” Fairly stated. And in 1961, Alston would say, “He gets on base. He can punch the ball on the hit and run. He steals and never throws to the wrong base. He knows how to get a walk. He has all the little things that go to make up a good ballclub. … I don’t think he’s ever been late a day in his life.”23

Gilliam rewarded Alston’s patience in 1956 with the infielder’s best offensive performance to date. Playing 102 games at second base and notching outfield innings in 56 more games, Gilliam finished with his only .300 batting average and flirted with a .400 on-base average, finishing with a career-high .399. He drew 95 walks and struck out only 39 times. His base-stealing improved (21 stolen, nine caught). He was chosen for the All-Star team, and finished fifth (his career high) in the Most Valuable Player voting.

For the rest of the 1950s, however, Gilliam would not have another season that looked appealing measured by the stats newspapers printed. He did, however, continue to do the things the Dodgers most valued him for. In 1958, he played mostly in the outfield, and more third base than second base. Further, he lead the National League in a category that was not measured at the time and usually is not even today: at-bats per strikeout, with 25.2. He would lead the league the next two seasons, and also in 1962 and 1963.

In 1959, he moved to third base full time so Charlie Neal could patrol second. And he continued to get on base from the lead-off spot (.387, sixth in the league). He led the league in walks (96 of them). After regaining his starting spot from Jim Baxes,24 who was given the job for the first eight games of the season, Gilliam led off in the next 64 games. He got on base at least once in 61 of them, and did the same in 84 of his first 89 starts. It helped him to get his second and last All-Star team roster selection, and he was again on a World Series winner

The general rule in baseball is that everybody gets one nickname. If the player has unusual physiognomy, they’ll receive a descriptive name (such as Fatty Fothergill or Slats Marion). If he behaves in a way considered unusual, he gets a personality name (like “Bananas” Mostil or “Charlie Hustle” Rose). Most often, players don’t have a personality worth commenting on, and one ends up with all or part of one of their names with an “ey” suffix tacked on (Domingo “Ming-ee” Ramos, or Paul “Paul-y” Sorrento).

But James William Gilliam, while mostly “Jim,” collected other names with wild abandon. He played games in the Negro Leagues under a nom de gant, “Frank Willem.”25 The nickname he got from Tubby Scales, “Junior,” was one he carried through much of his major league career, and the one he is best known by, until, as one of the oldest Dodgers, he found it condescending or merely anachronistic.

His teammates called him “Jimmy” or “Junebug” or “Sweet Lips” (the last because of the way he tightly pursed his lips when he swung at a pitch). Though his most noteworthy nickname, in contrast to his low-key personality, was “Devil.” He got that one because in Spring Training after a day’s work, he would take a modest bankroll to a pool palace in Gifford, a town near Vero Beach, walk in, lay his bills on a table and announce, “Who’s going to pay the Devil his due?”26

By the time he was a coach, the young players tended to call him “Devil,” even though many did not know the origin of the name.

Gilliam’s 1960, 1961 and 1962 seasons showed a decline in power relative to his 1950s’ marks (slugging roughly .330 versus the roughly .370 he had had up until then), but he maintained his OBP at around .360.

One reason for this was a roster shift in 1959. The arrival of rookie Maury Wills, a better base stealer than Gilliam, presaged a changed role for the veteran. By 1960, Wills started 60 games as a leadoff batter, with Gilliam usually batting behind him, and 74 games in the eighth slot with the pitcher batting behind him. The significant difference in Wills’ stealing success was gargantuan.

The Dodger front office noticed that when Wills was batting lead-off with Gilliam behind him, he notched 32 steals while getting caught only five times. Projecting those numbers out to the roughly 140 games a regular typically played, Wills could be a league-leader (75-12), with 100 runs scored – a big harvest in a climate for offense that had dampened from the 1950s.

Batting second, Gilliam could get on base as well as the upper-tier NL leadoff men and amplify Wills’ chances to steal. Sensing the value for the team, Gilliam made the transition without batting an eye. According to teammate Ron Fairly, he came to work without a typical competitive athlete’s ego.

“Junior played to win ballgames,” Fairly said. “He didn’t care who was the player who won the game so long as the Dodgers won the game. Jim didn’t worry about personal things like that.”27

The difficult to please and proud of it coach Leo Durocher, said of him, “He never – and I mean never – misses a sign. He does everything right. He’s a double pro.”28 Added Gilliam’s long-time skipper, Walter Alston:

“He doesn’t make any mistakes…He gives you 100 percent, day in and day out. He never moans. He’s a good team man. If I had eight like him, I wouldn’t have to give a single sign.”29

The visual acuity and mental quickness that provided him the reputation of never missing a sign (or perhaps even needing one) served him well batting in the second spot in the lineup. Gilliam claimed, and Alston and some teammates affirmed,30 a capacity no other ballplayer ever claimed or had claimed for him that the author can find: that Gilliam could see the kind of break from first base Wills had gotten from the corner of his eye, while still seeing enough of the pitch to let it go (if he judged Wills had the base stolen) or attempt to foul it off (if he guessed Wills was dead meat.)31 As reported late in the season:

“I try to help him. … Lots of times there are pitches I could swing at, but I see Maury out of the corner of my eye and take the pitch If I think he’s going to get the base. Or else I’ll take a strike, even two strikes to give him a chance to steal it. If it looks like he could be caught, I’ll hit at the pitch. Maybe I’ll punch it through and Maury’ll be able to make it to third. Or else I’ll foul it off and he’s not out.

“Not a man in baseball can do it better,” said coach Leo Durocher, “because Jim’s a real mechanic with that bat. He’s the best two-strike hitter in baseball. 32

By 1962, Wills and Gilliam had perfected their teamwork, and it paid off in Wills’ then-record stolen base mark: 104 steals with only 13 caught-stealing. The shortstop also scored 130 runs and won the NL’s Most Valuable Player (MVP) Award. It helped the team finish with 101 wins, tied for first, before losing a three-game playoff with the San Francisco Giants. Even with the Giants locked in on the Dodgers’ running game, Wills stole five bases without being caught while Gilliam was at bat.

In 1963, opposing batteries started paying more attention to shutting down Wills. Gilliam produced his best offensive numbers yet, an OPS+ of 121 (OPS+ is a measure of a player’s offensive production compared to the rest of the league; an OPS+ above 100 is above the average), based on his .282 BA, .354 OBP and .383 SLG in the first year of the expanded strike zone, stealing 19 bases while getting caught five times (79% success rate, his career high). Gilliam finished sixth in MVP voting, behind teammates Sandy Koufax and Ron Perranoski.

As always, Gilliam was also a difficult baserunner to pick off. In 1963, he was not picked off once, and for his career he was picked off only 23 times while stealing 203 bases, a ratio of 8.8 steals per time picked off. In comparison, Wills was picked off once for every 5.2 bases he stole, and even all-time stealing deity Rickey Henderson did not reach Gilliam’s level, getting picked off once per 7.2 steals.

By the end of 1963, Gilliam started talking about the end of his playing career, and told the Sporting News that after the 1966 season, he would like to retire and become a coach or manager. However, there had been no African-American managers in professional baseball,33 and only one coach, Buck O’Neil, who worked for the Chicago Cubs starting in 1962.

In 1964, the Dodgers fell back to earth after winning the World Series in a sweep over the Yankees the previous year, and Gilliam was part of that trend. After defending his second-base job against Nate Oliver, while also taking the time to mentor the younger player, he shifted to third base when prospect Johnny Werhas fizzled even though he was out-hitting Gilliam. Continuing to struggle at the plate, Gilliam became a bench player for the first time in his career, often coming in as a defensive replacement for rookie Derrell Griffith, whose bat was proficient but who was badly overmatched at the hot corner. The result was one of Gilliam’s least effective campaigns at the plate (.228 BA, .318 OBP, and .287 SLG, with an OPS+ of 78), while the Dodgers fell to 80-82 for the year.

As a result, the Dodgers moved up Gilliam’s coaching-career schedule, making him their first base coach for the 1965 season and making 23-year-old John Kennedy, acquired with pitcher Claude Osteen in the deal that sent Frank Howard to Washington, their third baseman. Kennedy started the first ten games and posted a .185 average. From games 11 through games 44, they tried Dick Tracewski, who produced no better, posting .217 BA, .313 OBP, and .257 SLG numbers. After 30 scoreless Dodger innings, Buzzie Bavasi called a meeting of the front office and dugout management. According to Bavasi:

“We talked over several possibilities… Finally, I said, ‘Let’s reactivate Old Slowfoot.’ Gilliam, attending the meeting as a coach, looked at me out of the corner of his eye. We were playing the Cardinals that night. He said, ‘You picked a fine day to bring me back. We’re going against [Bob] Gibson tonight. Wait until tomorrow.’”34

Gilliam had kept himself in shape, perhaps because he had always been the fallback plan. So at the end of May 1965, he was back at third base. He reached base in each of the first 12 games he started, scoring 10 runs from the No. 2 slot, posting a .386 BA, .491 OBP, and .568 SLG, with a pair of homers. The boost to the anemic Dodger offense was significant, and was a key reason the Dodgers won the pennant and made it back to the World Series, this time to face the Minnesota Twins.

As he had in 1955, Gilliam would play an important defensive role in a Dodger World Series Game 7 win. This time, it was not because he was shifted for a better defender, but because the out-of-retirement 36-year-old made a critical play himself.

Sandy Koufax was pitching with just two days’ rest. Without perhaps his best stuff that day, the lefty took a 2-0 lead into the bottom of the fifth inning. After a foul-out to Gilliam, Minnesota’s Frank Quilici followed, roping a double. Koufax walked powerful righty Rich Rollins, bringing up Zoilo Versalles with runners on first and second base. Versalles pulled a curveball fair, right over the bag at third that looked to be curving towards the stands, likely to score the runner from first and tie the game. Gilliam, getting a quick break on the ball, back-handed it, changed direction and beat Quilici to the bag, forcing the runner. It proved to be the Twins’ last hard-hit ball: Koufax settled down and the Dodgers won the Series – the fourth time in Gilliam’s career that the Dodgers were champions.

Gilliam’s stab in the tense situation won him recognition. At the time, many considered it to be one of the great defensive plays ever in a World Series.35 The National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown asked for the glove with which Gilliam had snared the Versalles shot. It is still on display there.

The Dodgers tried the coach-player experiment again in 1966, but Jim’s batting abilities, shrunk down now to a still-sharp understanding of the strike zone and his ability to find the hole between first and second base with a runner being held on first, wasn’t enough to justify keeping it going. At the end of the season, with the usual lack of fanfare attended to most of his career, Jim Gilliam retired and became the Dodgers full-time first-base coach.

He retired with only two statistically noteworthy career accomplishments and one minor National League mark.

During his 11 years as a starter, he was in the league’s top ten in walks nine times. He played in 1,956 games. Among players who played all their career games for a single team, however, he ranks 13th all-time in games played. Finally, on July 21, 1956, he joined John Montgomery Ward in sharing the Major League record for assists in a game by a second baseman (12).

Jim Gilliam had two essential prerequisites required of a good coach or manager. First, he paid close attention to the game and worked to pick up knowledge as a part of his work. Second, he was always looking for an edge that could favor his team.

As an anecdotal example, Jim was able to push a run across a run against a pitcher who owned him, in a key game, by using an unusual tactic. On September 4, 1962, with the Dodgers holding a 2-1/2 game lead over the rival Giants, Gilliam came up to bat with two outs in the fourth inning, with catcher John Roseboro on third and two outs. The pitcher was Billy Pierce, against whom to that point he was 1-for-9 in his career.36 Batting right-handed against his lefty nemesis, Gilliam on the first pitch called for Roseboro to break for home and try to steal it. On the pitch, Gilliam leaned far over as though to swing and obscured the Giant catcher’s view until Roseboro was too close to tag out, Roseboro scoring what would prove to be the winning run.

And even though the infielder was not statistically outstanding at fielding, he polished his positioning for hitters by rigorous application of observation, measurement and analysis. Ron Fairly: “He had a tremendous feel for playing the hitters. Knowing the pitcher, knowing what the pitcher might throw and then positioning himself defensively accordingly.” Like some other middle infielders, Gilliam made a point wherever possible to read the catcher’s signs to give himself an edge in positioning. But he went above and beyond what most second basemen do and actually positioned his first baseman (a position from which the fielder cannot read the catcher’s sign), more like a coach than a player.

According to Fairly, when he was a first baseman and Gilliam was playing second (mostly 1961-1964):

“There were times that he’d call me. ‘Ronnie,’ he’d say, and he’d move over toward second [base] and I’d move over that much, too. Another time when he would move closer to me, and he’d holler at me to move those times. He was tremendous at positioning.

“He also did one other thing. When there was a left-handed hitter up at the plate and the pitch was called to be a change-up or a curve ball…he could see the signs, he’d let me know that an off-speed pitch was coming. Just as the pitcher would come to his set or start his delivery, Jimmy would give me a code word. I could hear him and that told me, ‘Here comes an off-speed pitch.’ There’s no way the opposing team can relay that to the hitter in time… He would let me know all the time when an off-speed pitch was coming. It helped me, made me a lot more alert, knowing that in that situation, there’s a better chance the ball’s going to be hit down that way.”37

Beyond anecdote, Bill James created a measure designed to be a proxy for Baseball IQ, a stat he called “Player Performance Index,”38 a combination of specific batting, running and defensive statistics meant to pull out “percentage players.” Gilliam ranks third all-time for that measure, behind only Joe Morgan and Max Bishop.

Gilliam coached first base for the Dodgers for Walter Alston’s remaining tenure as manager, which ended with Alston’s retirement after the 1976 season. It was Gilliam’s dream to manage in the major leagues. He got a taste of managing between the 1973 and 1974 seasons. He was skipper of the San Juan team in the Puerto Rico Winter League, where a blend of major leaguers and other talent from around the Caribbean played. In the major leagues, however, no African-American had managed yet. The most likely African-American candidates were celebrities such as Wills or superstars such as Willie Mays or Frank Robinson who newspaper stories touted as likely trail-blazers. But a trickle of stories did emerge about Gilliam’s dream, one he pursued as quietly as everything else he did in his public life. For example, a writer for the Chicago Tribune opened a June 6, 1973 story titled, “Gilliam waiting patiently for chance to manage” with the lead: “Jim Gilliam, the Dodgers’ coach, would be managing somewhere in the majors today if he had one of two things: [a] an offer to manage or [b] white skin.”

As was his habit, he was patient and modestly confident. He was not unhappy at the thought other African-American candidates might get a managing job before him; as usual, he was looking beyond his own success. “No, it doesn’t bother me, although I think I may be better – prepared than any of the others,” he said to Los Angeles Times reporter Ross Newhan. “I’ve been in baseball for 25 years and during that time I haven’t just gone through the motions. I’ve studied and applied myself. I know I’ll get the chance and I’ll be ready.”39

Wills campaigned publicly and hard for that first managerial job. On a Pittsburgh Pirates television broadcast, he told Bucs announcer Bob Prince that Gilliam was not managerial material. But it was Robinson who would become the first black manager in the major leagues, hired by the Cleveland Indians at the end of the 1974 season. Indians’ general manager Phil Seghi who had hired Robinson said he had considered many candidates, both White and Black, including Gilliam.40

When Alston retired in 1976, two coaches – Gilliam and Tom Lasorda – were the leading candidates to replace him. The campaign was very short, with Lasorda getting the position two days later and asking Gilliam to stay on. For the next season, Gilliam also became the team’s batting instructor.41 His special project was strikeout-prone Steve Yeager, who had sagged to a .216 batting average; in 1977, Yeager hit .256, notched his career high in walks and had an OPS+ of 107.

The long-time Dodger stayed loyal to the team and soldiered on for Lasorda and the club. He waited quietly for someone to recognize his aptitudes and give him a chance to manage. He never got another interview.

He made a special effort to mentor young players. Perhaps because he’d been shy himself, he tried to help them get socialized. This included providing them with a sense of baseball history. For example, at spring training he would take players to the aging “colored”-only hotels and restaurants that segregated Florida had made his generation of African-Americans stay in when the team was getting ready for the season.42

On September 15, 1978, with the Dodgers coasting to another division title, Gilliam drove Lasorda to the ballpark early so they could talk about setting up the game, dropped him off, and went home for a rest. He suffered a cerebral hemorrhage and went into a coma from which he never awoke. He died on October 8, at age 49, the day after the Dodgers won the National League title.

At his funeral, 2,000 people came to Los Angeles’ Trinity Baptist Church, including Yankee slugger Reggie Jackson. Rev. Jesse L. Jackson gave the eulogy, titled “Greatness Against a Headwind.” His words included this passage:

“Small wonder he died from internal bleeding. … Any time a man must alter his dream and camouflage his ambitions … he bleeds a little every day. Any man who only catches – even though he doesn’t say so – wants to hit sometimes. And even though he did not make it, family, don’t be disappointed. He was running against a headwind.”

He finished with a reference to Gilliam at least getting to see two African-Americans become managers before he died. “He had his high noon. He crossed home plate even though society wouldn’t put his score up on the board.”43

Dodger Dave Lopes, like Gilliam a second baseman and a lead-off hitter, dedicated his Series to his coach, the man he called, “father, friend, and locker room inspiration,”44 Lopes’ two home runs and five RBI led the Dodgers to a decisive 11-5 win in Game One over the New York Yankees. While rounding first base on his first homer run trot, he pointed to the sky with one hand. After the second homer, he pointed with two arms extended, each forefinger pointing straight up. This appears to be the first time such gestures of homage were used in a major league game, though it is now standard operating procedure for many players.

A few days later Los Angeles Times sports columnist Jim Murray penned a tribute for Gilliam, the versatile non-star. His effort to describe Jim’s end began with these words:

“I guess my all-time favorite athlete was Jim Gilliam. He always thought he was lucky to be a Dodger.

“I thought it was the other way around.”

Acknowledgments

Steve Steinberg contributed significant research work without which this biography would not exist. Steinberg, along with Don Malcolm, Steve Manes and Tom Heinlein all made essential improvements by graciously editing and improving this work.

Photo credits

Trading Card Database and NoirTech Inc., courtesy of Larry Lester.

Notes

2 Lew Paper, Perfect: Don Larsen’s Miraculous World Series Game and the Men Who Made it Happen, New American Library, 2009, p. 218.

3 Sidney Fields, Daily Mirror (New York), May, 1953.

4 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues, Carroll & Graf, 1994.

5 Bill Ladson, MLB.com biography of Sammy T. Hughes

6 Ladson, “Sammy T. Hughes.”

7 www.cubanbaseballcards.com/pr48-49toleteros.html, www.robertedwardauctions.com/auction/2007/460.html

8 Howard Jacobson, newspaper unknown, March 1953.

9 Jacobson.

10 Joe Black, Fay Vincent Oral History Collection, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

11 Jacobson.

12 Joe Black’s unfinished manuscript had details about Gilliam’s Cub excursion, graciously shared with me by Chuck Schoffner.

13 The Sporting News, April 8, 1953 (reference in Perfect).

14 New York Times, September 7, 1979, (reference in Perfect).

15 Lloyd McGowan, Complete Baseball, February, 1953. Frank Graham wrote in an April 1953 piece for the New York Sun that it was $1,500.

16 www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1952/YS_N1952.htm, www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1952/WBRO01952.htm

17 Carl Erskine telephone interview with author, November 2009.

18 Tommy Holmes, Brooklyn Eagle, September 1953.

19 New York Times, December 1953. Undated story from National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

20 New York Times, December 1953.

21 F. Monardo, newspaper unknown, February 15, 1956. Clip from National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

22 Author interview with Ron Fairly, July 2006.

23 Jimmy Cannon, New York Journal-American, 1961.

24 Interestingly enough, Baxes hit the snot out of the ball for those games, with a .280/.379/.560 offensive mark, though it’s possible his seven errors soured the team on his being a starter.

25 Riley.

26 There are several phrasings reported in the archives. Fairly, who as a pretty good pool player, may have been there at the time, and reports it as “Who wants a piece of the Devil?”. Lew Paper, whose research is meticulous, has it from the L.A. Examiner that it was “Who wants a piece of the Devil’s action?”

27 Author interview with Ron Fairly, July 2006.

28 Bob Hunter, The Sporting News, April 4, 1964.

29 Hunter.

30 Hunter.

31 Melvin Durslag, Los Angeles Herald-Examiner, May 1966.

32 Milton Gross, New York Post, September 1962.

33 Former Kansas City Athletic Héctor López is credited as being the first Black manager in the minors. He broke this line in the 1969 season.

34 Melvin Durslag, Los Angeles Herald-Examiner, May 1966.

35 Paper, 218.

36 Of all the pitchers who Gilliam faced at least 15 times, Pierce was the toughest on him. Their career match-up resulted in Gilliam totaling 1-for-20 with a pair of walks (.050/.136/.050). Incidentally, the pitcher against whom he had the most success was the Braves’ and Mets’ Ken Mackenzie, 6-for-13 with a homer and four walks (.462/.533/.769).

37 Author interview with Ron Fairly, July 2006.

38 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, p. 478-9.

39 Ross Newhan, Los Angeles Times, March 13, 1971.

40 New York Times, October 6, 1974.

41 “Gilliam Gets New Duties – With a Bat,” Los Angeles Times, February 9, 1977.

42 Author interview with Davey Lopes, May 2006.

43 Jet, November 2, 1978.

44 Associated Press (no byline), October 12, 1978.

Full Name

James William Gilliam

Born

October 17, 1928 at Nashville, TN (USA)

Died

October 8, 1978 at Inglewood, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.