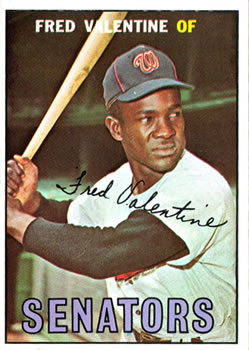

Fred Valentine

Shortly after his birth, Fred Lee Valentine’s aunt dubbed him “Squeaky” for the noises he made as a toddler. Since he was too young to argue with her about the name, it stuck and remained with him through high school and college and even into his pro career. It bespeaks the constancy of the man, his superb grounding in family and his way of taking all that the world gave him and making the most of it. As part of the wave of African Americans who made their way to the majors in the post-Jackie Robinson era when discrimination and racial hostility were still common on ball fields across the South, Fred needed the strength of character that a strong family life provided.

Shortly after his birth, Fred Lee Valentine’s aunt dubbed him “Squeaky” for the noises he made as a toddler. Since he was too young to argue with her about the name, it stuck and remained with him through high school and college and even into his pro career. It bespeaks the constancy of the man, his superb grounding in family and his way of taking all that the world gave him and making the most of it. As part of the wave of African Americans who made their way to the majors in the post-Jackie Robinson era when discrimination and racial hostility were still common on ball fields across the South, Fred needed the strength of character that a strong family life provided.

Fred was born in Clarksdale, Mississippi, January 19, 1935, but his family soon moved to Memphis, Tennessee, where he attended schools starting with elementary school and ending at Booker T. Washington High School from which he graduated in 1953. Memphis was the big city and had eight all-black high schools that provided a stiff level of competition in sports. Yet, before he reached that level, Fred found no organized sports leagues for him and his friends.

Young African-American kids made their own outlets for their love of sports, playing on vacant lots, in the street where they dodged cars, and just about anywhere they could fit a group of neighborhood kids who wanted to go up against the best from another neighborhood. Fred’s family had a large back yard, and the neighborhood kids would often gather there to play. Fred shared his love of sports with the same group of guys from an early age, from Manning Street and neighborhood sports teams all the way through high school. When there were not enough guys to make up a team, they played cork ball.

Fred ultimately found organized sports at the high school level where his speed and agility were best suited to football and baseball. He is ambidextrous — able to use his left and right hands with equal aplomb — and that ability helped out on the football field where he started as the quarterback in his sophomore year. “I could lateral the ball both to the left and right on running plays with equal dexterity and that helped me beat out a junior quarterback my sophomore year.”1 Fred also had a good arm, but admitted that having the backfield coach also as his baseball coach did not hurt his success as quarterback.

Fred achieved his greatest success at Booker T. Washington on the baseball field. He played shortstop, the position that was generally reserved for the best athlete on the team. When he had his first tryouts with the Baltimore Orioles, he was still a middle infielder. But the Orioles had Brooks Robinson at third base and Luis Aparicio at shortstop, so Fred was told to move to the outfield.

Fred credits his parents with keeping him focused in high school, both academically as well as on sports. Speaking about his education in a Washington Post article in 1966, Fred said, “You know how education is for Negroes in the South. My dad was determined that I was going to get a college education.”2

The Orioles were not the only teams to have an early interest in Fred. He talked to big-league baseball scouts from the St. Louis Cardinals and Pittsburgh Pirates, but Fred followed the advice of his parents and did not sign a contract with anyone. He chose instead to attended Tennessee Agricultural and Industrial College, a historically black college now known as Tennessee State University.

Fred himself said he “had read a lot about how terrible major-league clubs are for trying for luring the poor boys out of college.”3 Fred Valentine saw his first success as an athlete as the quarterback for Tennessee A&I. “I made the varsity as a freshman and in my sophomore year I was fifth in the nation for offense for small-college backs.”4 As was the custom during that era, he played both offense and defense. He played baseball and football in college and at the beginning of his junior year was faced with a decision.

Fred’s baseball coach, Raymond Whitman, advised him to concentrate on baseball, noting that there were no black quarterbacks in the NFL. Despite being recruited by the Green Bay Packers, Cleveland Browns and Pittsburgh Steelers, Fred chose baseball and went for tryouts with the Cardinals and Pirates. He was offered a $2,000 signing bonus. The money was not good enough to lure him away from college. He stayed at Tennessee A&I, where he graduated in 3 1/2 years.

The Orioles had advised him that they would sign him upon graduation, and he was grateful for that support and reported to the Orioles’ minor league team in Vancouver. “I guess my biggest thrill was when I signed my contract with Baltimore,” Fred admits now.5

He was signed by top scout Jim Russo, who insisted that Fred meet him at a downtown Nashville hotel for the signing. “You come in the front door. You’re a big-league ball player now,” Russo told him in 1956. Fred remembers dinner at the hotel as the “finest he had ever had in his life.”6

Fred traveled to Baltimore for a formal tryout with the Orioles that was attended by Paul Richards who served as both general manager and field manager for the Orioles during the late 1950s and early 1960s. Also in attendance was Bob Boyd, the first baseman for the Orioles in 1956. Boyd, known as “Rope” for his line-drive power, was from Memphis and it was a thrill for Fred to tryout in front of Boyd, who had achieved great success with the Memphis Red Sox of the Negro Leagues while Fred was still in high school.

Fred signed a contract with the Orioles that stipulated that he would play at the Triple-A level to start, so he had a brief stint in the Pacific Coast League with the Vancouver Mounties at the end of the 1956 season.

Fred’s long apprenticeship began in earnest during his first full season in the minors playing for the Aberdeen (South Dakota) Pheasants. The Pheasants played in the Northern League, which included teams from Montana, North Dakota and Canada. Fred remembers the drive to Aberdeen as an arduous one that took three days. “I had never seen a pheasant before,” he added.7 Fred acquitted himself reasonably well in his first full season, hitting .271 with seven home runs.

As a college grad, Valentine was older than many on the Aberdeen roster and wanted to move quickly through the Orioles system. He was hoping to get a promotion to A-ball in Knoxville. The Orioles assigned him instead to Wilson, North Carolina, one rung up the ladder, but like the Knoxville Smokies of the Sally League, the Wilson Tobs played in a league comprised wholly of cities and towns from the Deep South.

It was common practice for major league organizations to place black players in a northern league for their first year. Branch Rickey had done so with Jackie Robinson and others gave African-Americans their first taste of professional ball where racial hostility was muted. However, it was just as common for successful players to then be moved to minor leagues in the Deep South to see how well they could manage the hostilities that greeted blacks there.

In 1958, when Valentine joined the Wilson Tobs, they played in the C-level Carolina League. By this time the integration of baseball was going full tilt across the South. Major leaguers like Ed Charles and Hank Aaron had led the way in the early 1950s breaking the racial barrier in minor leagues across the South. They experienced threats on their lives, vicious taunting from the stands and living conditions that were decidedly second-rate compared to that of their white teammates.

Yet they endured as “Jackie’s disciples.”8 It was not always easy. In 1951 Percy Miller was the first African-American to play in the Carolina League and he was able to endure the torment only two weeks before leaving the team. In 1953, Bill White – All-Star first baseman — was the first black ballplayer to last an entire season in the small North Carolina towns that comprised the league among them Burlington, Danville, Fayetteville and Reidsville.

Valentine remembers the league as having some very rough towns. “Greensboro was the worst,” he recalled.9 He recalls some tough nights there, but when Fred won the MVP Award for the best player in the Carolina League at the end of the season, the Greensboro GM was the one who presented the award at the ceremonies in Wilson.

While there were ugly taunts from fans, Fred remembers them in retrospect with humor, “Those folks had to practice some of those things they said to me. They were that good,” he remembers smiling. But were they really funny when he was on the field listening to racial taunts? His reply: “How else are you going to get through it?”10

One of Fred’s fondest memories from that year occurred midway through the season when the team was playing before the hometown fans in Wilson. Valentine’s play the night before had been exemplary and to cap off an exciting win for the Tobs, Fred had stolen home. The papers were buzzing with the story on Sunday morning after the game. An after-church crowd filled the stadium.

Black fans were seated in segregated bleachers along the right field foul line. The stands were not well constructed, lacked any cover and that day, as they filled to capacity, they began to sway until they crashed to the ground. Although no one was seriously injured, the ownership of the Tobs had a crowd of anxious fans that had paid to see a ball game. As the hero of the night before, someone in the Tobs’ brain trust approached Fred and asked for his suggestions.

Fred told the general manager of the team that he believed the black fans could coexist with the white fans. The GM was skeptical but Fred offered, “Everybody knows everyone in this town anyway, just give it a chance.”11

An experiment dictated by the necessity of the moment was a huge success. Black patrons found friendly white faces among those in the grandstand and sat next to them during the game and everyone settled in agreeably. It was the end of segregation for the Wilson Tobs and the segregated bleachers were never rebuilt.

The season in Wilson was Fred’s most successful of his young career. He hit .319 with 16 home runs and 49 extra-base hits to merit him the Most Valuable Player award in the league, which likewise earned him a huge jump within the Baltimore system.

To begin the 1959 season he moved up to the Orioles’ affiliate in the Triple-A International League, the Miami Marlins. Fred was 24 and still making great progress toward the majors. In his first season playing at Miami, Fred hit .257 with 11 home runs on a team that had only five players with double-digit homers and a team batting average of .243. His success with the Marlins earned Fred a September call-up to Baltimore. While with the big club he hit .316, appearing in a dozen games and garnering 22 plate appearances.

His personal life changed in important ways that fall as well. He had met an attractive young woman while playing in Wilson. Fred was the best baseball player in town, but when he stopped his wife-to-be to ask about the best place to eat in town, she continued down the street without even acknowledging Fred. He eventually got to know her that summer, and they maintained a long-distance relationship until she became Helena Valentine after his first major league stint that September. Their wedding was postponed because of his call-up, but their patience was rewarded with a relationship that endures today more than fifty years later.

Valentine returned to Miami the following spring believing he was on his way to a major-league career. But Valentine would toil for four more seasons in the International League before getting another chance to play for the Orioles at the big-league level. During those years the Orioles moved their International League affiliate to Rochester, New York, where Fred continued to be a mainstay of the team. He was a starting outfielder and one of the better hitters in the lineup. In 1961 he had a slash line of .271/.337/.427 that exceeded the team average in all three categories.

But it was not good enough to get him another chance with the big club. The Baltimore Orioles had been one of the early American League teams to integrate their everyday lineup. Negro Leagues star Bob Boyd started at first base from 1956 — the third season of the relocated St. Louis Browns franchise — until the end of the 1959 season when he retired. He was joined by Willie Tasby, who took over in center field briefly in 1959.

But while players like Tasby outperformed other outfielders, they did not stick. In 1961 another African American player, Earl Robinson, got a chance and performed well but white veterans like Dick Williams received the lion’s share of the playing time despite putting up less than riveting numbers. It almost seemed as if the yardstick for evaluating the performance of African American players was slightly different.

At this point in Fred’s story, there is room for interpretation. Jim Russo, who had scouted Fred originally for the Orioles and remained a friend and supporter, believes that Fred had earned a chance with the big club. He questioned why that chance did not come and believed that racial considerations were at the core of the many years Fred spent in Triple-A laboring while less talented players earned promotions and old-timers continued to clog the Baltimore outfield.

The sentiment was echoed by Tasby: “I feel as though Baltimore held me back in the prime of my career. I wasn’t given an opportunity.”12 Tasby helped break the color barrier in the Southern minor leagues like Fred Valentine, but did not believe that he was given the same chance to make the majors that white players of similar or lesser talents were given. Fred Valentine could make the same case, although he never has.

At the end of the 1963 season, the Washington Senators purchased Fred’s contract from the Orioles for $25,000, saying they were impressed with his switch-hitting ability and his speed. Washington made the judgment in the few games they saw him play that season against the Orioles. Washington manager Gil Hodges slotted Fred into a right-field platoon with Jim King, but King got the majority of the playing time. Fred logged 212 at-bats and logged an anemic .226 batting average. King had the better year with a .241 average and 18 home runs on a team that had little power.

Fred’s perspective is more philosophical now. Looking back, he admits that the Baltimore outfield was crowded with possibilities. Paul Richards was always good to Valentine, and he valued the chances he was given. But when a new opportunity came along, one to play in Washington for the expansion Senators, Fred Valentine was relieved to leave the Orioles behind. Fred had finally found a home with a team willing to give him substantial playing time and a chance to show what he could do against major-league competition.

One of the stars for Gil Hodges’ Senators team was Chuck Hinton. Hinton was another black player on a team that for many years had eschewed them. In the 1950s, when Calvin Griffith made the personnel decisions for the original Washington Senators, there had been no real attempts to integrate the team.

Hinton was the best black player to take the field for Washington during the course of the expansion club’s history. He played left field and maintained a .280 batting average during the four years he played for the Senators (1961-64) averaging 12 home runs and 23 steals over that period. He had the same combination of speed and power to which Fred aspired. Hinton was traded to the Cleveland Indians at the end of the 1964 season, providing an opening for Valentine, but when the 1965 season began, Valentine was playing Triple-A baseball in Hawaii.

Bob Addie, the noted Washington Post sportswriter, opined that Hawaii was quite happy to have Valentine on the roster. He was hitting .400 when Addie’s column appeared in late April, and finished the season with a slash line of .324/.419/.534.13 He had 25 home runs and 58 stolen bases. He was 30 years old and it was his best season in baseball, one that few players ever realized in any league, but his prime playing years were slipping away from him. The Senators called him up in September and he got into a dozen games.

The 1966-1968 seasons represent the heart of Fred’s major league career. He was 31 years old when play began in 1966 and he was ready. He had an amazing year of success playing for the Islanders, the best of his career, and he would carry it over into his first full year in the majors.

The 1966 Senators were led by slugger Frank Howard. Hondo had come over from the Los Angeles Dodgers in 1965. At 6-foot-7 he had prodigious power, but failed to fully realize the potential equal to his size. Tall and lumbering, Howard had no real position on the field. He spent most of his time in left field while Hodges used both Don Lock and Valentine in center that season. Fred remembers having to play all of center field and a good bit of left when playing alongside Howard in 1966.

The expansion Senators were never a competitive team during the entirety of their 12 seasons in the nation’s capital; the best any Senators team did was 10 games over .500 in 1969. The ’66 Senators, meanwhile, finished last in the American League. Fred Valentine might have been their best player that year. His .276 batting average was only a tick below Frank Howard’s .278, and his 16 home runs were similarly close to Howard, the team leader with 18. But Fred played solid defense and stole 22 bases.

Fred’s solid contributions gained him press attention. A May 22, 1966, piece in the Washington Post led off, “Success wears well on Fred Valentine.” The initial focus of the story was Fred’s wardrobe, said to be the best on the team. Yet the real issue was the series Valentine had against the Angels. “His eight hits including a homer, triple and a double in consecutive games against the Los Angeles Angels was the best two-day show ever put on by a member of the expansion Senators.”14

It was one of the most detailed accounts of Fred’s playing history to appear in the local Washington press and recounted the racial hostility he had encountered in North Carolina while playing with the Wilson Tobs, how he met his wife and his respect for manager Hodges. The press attention would grow during the season and by its end, with the Senators trying to finish out of the cellar for the first time, Gil Hodges would state that there were only two players on the team he would not trade, Valentine and catcher Paul Casanova — the two African American regulars on the team.

The Los Angeles Angels were Fred’s favorite team in 1966. In 18 games against them that year, he hit .448 and had a slugging average of .776 with four home runs. One of the highlights was a grand slam he hit July 25 in a game easily won by Washington. Late in the season the Senators were looking up at the Angels hoping to catch them in the standings, but despite the best efforts of Valentine, Washington slid to last in the American League once again.

Fred and the rest of the team had high hopes to build from the relative fortunes of the prior year. And improve they did: sixth in the ten-team league with a winning percentage of .472. Although Fred hit only .234 for the season, it was the first of several seasons that tilted heavily in the pitchers’ favor. The team batting average for the Senators that season was .223.

As the 1968 season loomed, Fred was still a mainstay of the team. He was readying for the season in early April, standing in right field in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, during a spring training game against the Yankees when the public address announcer interrupted play with the news that the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated in Fred’s home town of Memphis. Fred said he remembers that moment to this day. It will always be with him along with the confusion that followed as the team returned to the riot-torn city of Washington. Major portions of the city were consumed in flames.

When the team returned for the season opener, they could see smoke rising from the city as their plane prepared to land. National Guardsmen patrolled the city and the area around D.C. Stadium, home to the Senators. One of those guardsmen was Senators shortstop Eddie Brinkman, who did not make the Opening Day lineup. Attendance for that game was reduced and the crowd subdued.

Fred got off to a slow start that season, slowed by an early injury that kept him out of the lineup for two weeks. As the weather warmed, so did his batting average, rising to .240 in early June. But Fred was 33 years old, and coming back from injury was more difficult. The Senators had a crowded outfield and on June 14, Washington traded Valentine to the Orioles for 25-year old pitcher Bruce Howard.

Fred returned to the team that had nurtured him as a youngster. Fred told reporters that he was sad to leave D.C., but happy to join the pennant-contending Orioles. The Orioles would finish second in the American League that season behind the eventual world champion Detroit Tigers. The 1968 season was Fred’s last in the majors. He spent the 1969 season once again at Rochester where he had a good year, but realized that his major-league career was probably over. He took one last shot signing with the Hanshin Tigers in Japan for the 1970 season, but the experiment was short-lived and he returned to the States and retired from the game.

Fred maintained his home in Washington even after the trade to Baltimore. At the end of his career, he attended graduate school at George Washington University and Antioch Law School. He began a long career at Clark Construction Group in Washington, where he worked in employee relations and subcontractor administration.

At the suggestion of Chuck Hinton, Fred and other former players in the Washington and Baltimore area worked to establish the Major League Baseball Players Alumni Association. The group was formed in 1982 to promote the game of baseball, involve major-league players in community activities, inspire and educate youth, and raise funds for charitable groups. They have sponsored dozens of golf tournaments, banquets and games between former players to these ends. Fred is currently the co-chair of the association and remains involved in his church and community.

Postscript

Valentine died at the age of 87 on December 26, 2022.

Sources

Addie, Bob. “Summer in Hawaii,” Washington Post, April 28, 1965. B3.

Addie, Bob. “Valentine Doesn’t Rue Being Football ‘Dropout,’” Washington Post, March 4, 1966. D1.

Addie, Bob. “Valentine Signs for $18,000, Vows Improvement Over ’67,” Washington Post, February 1, 1968. C1.

Adelson, Bruce, Brushing Back Jim Crow: The Integration of Minor League Baseball in the American South, Charlottesville, Va.: University of Virginia Press. 1999.

Minot, George, Jr., “Nats’ Valentine Has Lots of Heart,” Washington Post, June 18, 1967.

Personal interviews with Fred Valentine, April 2008, February-April 2013.

Telephone interview, Russ White, sports writer, Washington Star, March 5, 2013.

Notes

1 Personal interview, February 2013.

2 Bob Addie, “Valentine Doesn’t Rue Being Football Dropout,” Washington Post, May 4, 1966. C4.

3 Ibid.

4 Personal interview, February 2013.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Adelson, Brushing Back Jim Crow, 16.

9 Personal interview, February 2013.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Adelson, Brushing Back Jim Crow, 106.

13 Bob Addie, “Summer in Hawaii,” Washington Post, April 28, 1965. B3.

14 George Minot, “Valentine’s Lusty Hitting Suits Nats Fans,” Washington Post, May 22, 1988. C4.

Full Name

Fred Lee Valentine

Born

January 19, 1935 at Clarksdale, MS (USA)

Died

December 26, 2022 at Washington, DC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.