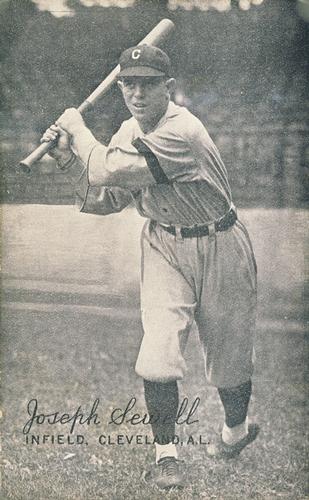

Joe Sewell

Opportunity from horrifying tragedy: That was what the death of Cleveland Indians shortstop Ray Chapman presented to 21-year-old Joseph Wheeler Sewell in the late summer of 1920. Chapman, a stellar shortstop for the contending Indians, died on August 17 after being struck in the head by a pitched baseball, and Cleveland had replaced him with second year shortstop Harry Lunte. On September 6, when Lunte pulled a leg muscle that left him unable to play, the Indians purchased Sewell’s contract from the New Orleans Pelicans of the Class A Southern Association. Sewell’s professional experience at the time amounted to 346 at-bats, yet out of necessity he was inserted into the middle of the infield of a team that was competing for the American League pennant.

Opportunity from horrifying tragedy: That was what the death of Cleveland Indians shortstop Ray Chapman presented to 21-year-old Joseph Wheeler Sewell in the late summer of 1920. Chapman, a stellar shortstop for the contending Indians, died on August 17 after being struck in the head by a pitched baseball, and Cleveland had replaced him with second year shortstop Harry Lunte. On September 6, when Lunte pulled a leg muscle that left him unable to play, the Indians purchased Sewell’s contract from the New Orleans Pelicans of the Class A Southern Association. Sewell’s professional experience at the time amounted to 346 at-bats, yet out of necessity he was inserted into the middle of the infield of a team that was competing for the American League pennant.

Sewell debuted on September 10, 1920, against the New York Yankees, going 0-2 at the plate. His arrival was expected to stabilize the infield, and despite his 15 errors in 22 games, 10 hits in his first 24 opportunities provided and unanticipated offensive bonus. The team capped Sewell’s first season with World Series win over Brooklyn, and Cleveland’s double play tandem of Bill Wambsganss and Sewell was set for the next three years. It proved to be the opening foray of what would become a Hall of Fame career for the shortstop.

Joe Sewell was born on October 9, 1898, in Titus, Alabama, to Dr. Wesley “Jabez” and Susan (Hannon) Sewell. One of three future major league players in the family, along with brothers Luke Sewell and Tommy Sewell, as well as cousin Rip Sewell, Joe Sewell grew up 30 miles north of Montgomery, playing baseball as a respite from his studies. Dr. Sewell wanted his sons to join the family business as physicians, but the boys had other ideas.

Joe starred in baseball at Wetumpka High School, and after graduating in 1916, enrolled at the University of Alabama, where he planned to prepare for medical school. He also played on both the football and baseball varsity squads and joined the Pi Kappa Phi fraternity. By his senior year, Sewell was sufficiently accomplished and popular to be elected class president, but it was on the athletic fields that he found his true calling. Sewell started for three years at second base for the Crimson Tide and was joined in the infield by future major league outfielder Riggs Stephenson at shortstop. The two would play together for Cleveland from 1921-1923. The 1918 Alabama team actually had five future major league players, with Dan Boone, Francis Pratt, and Rollie “Lena” Stiles rounding out the roster, and Joe’s brother Luke joined in 1919.

With all that talent, it was inevitable that the Tide should prosper. The 1918 team posted a 13-4 record, while the 1919 edition improved to 16-2 and the 1920 squad went 14-1 (winning the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Association title for four consecutive years). Sewell did his part, despite his short stature at 5’5” and only 155 pounds, by setting every hitting and fielding record possible at the university. Upon graduation in 1920, Sewell signed his first professional contract with New Orleans. Now playing for pay, Sewell relied on his one innate and practiced skill—he could always make contact at the plate. He was later quoted: “When I was a boy I’d walk around with a pocket full of rocks or a Coca-Cola top and I can’t remember not being able to hit them with a broom stick handle.”

When Ray Chapman was killed by Carl Mays’ errant pitch, and after replacement shortstop Lunte pulled a muscle in his left thigh, the Indians had little choice but to purchase Sewell’s contract from the Pelicans. Joe had hit a respectable .289 in Class A and had committed only twenty-seven errors in 435 chances, but Cleveland claimed him only because they were out of alternatives. “I’ve often wondered what my life would have been like if a ball hadn’t gotten away from Carl Mays,” Sewell said decades later. “…Because the moment that ball left Carl Mays’ hand, my life began to change.”

Joe disembarked the train in Cleveland with a brand-new suit of clothes, hastily purchased on a layover in Cincinnati, and little else. He made his way to the ballpark and proceeded to take a spot on the dugout bench for the next two games. Watching a big league game for the first time, he saw several players make spectacular catches and throws, and thought, “I don’t think you belong here, Joe.” When manager Tris Speaker put him in the lineup, Sewell asked him, “Are you sure?” The rookie’s first hit was a triple down the left-field line. “When I got to third I stood there and said to myself, ‘Shucks, this ain’t so tough after all.’”

Sewell was a left-handed batter, but threw right handed, and was so new to the professional game that he did not even own a decent bat. The day Sewell debuted, September 10, 1920, new teammate George Burns gave him a black forty-ounce bat to use. Sewell never broke that bat, and cared for it to the point of coddling what he called “Black Betsy” for the rest of his career. The bat is still displayed at the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame Museum in Birmingham.

Sewell played in the final 22 regular season games for Cleveland, and his 23 hits gave him a .329 batting average in his first major league month. Because he had been added to the Indians’ roster after September 1, he normally would not have been eligible to play in the World Series, but Brooklyn manager Wilbert Robinson accepted Cleveland’s request to waive that rule due to the circumstances of former shortstop Chapman’s death.

After Cleveland’s world championship, Sewell returned to the University of Alabama to continue his pre-medical education and engage in some amateur theater with the University’s Black Fryars, but in 1921 he went back to Cleveland and baseball when his younger brother Luke and good friend Riggs Stephenson joined the Tribe. On December 31, 1921, Sewell married Alabama sweetheart Willie Veal. Their marriage lasted 63 years, until Willie passed away in 1984, and produced three children: Joe Jr., James, and Mary Sue.

For the next 10 years he built a record that eventually ushered him into Cooperstown. Between September 13, 1922, and April 30, 1930, Sewell never missed a game for Cleveland. By the time his streak ended, at 1,103 consecutive games, it was second only to that of Everett Scott, and as of 2011 is still the seventh longest in major league history. Such stable longevity was only possible because Sewell’s bat forced his managers to pencil him into the daily lineup. Belying his physical stature, Sewell hit .318 in 1921, and excepting his .299 mark in 1922, kept his batting average above .300 until 1930. In addition to his ability to put the ball in play and get on base, he led the Indians in runs batted in for three seasons. In the field he was no liability, leading American League shortstops in putouts and assists four times.

His most remarkable gift, though, was in making contact with a pitched baseball. After striking out thirteen times in 1924, he whiffed only thirty-three times—in total—from 1925 to 1930 while playing every game of every season. The mighty mite with the forty-ounce bat simply refused to miss anything thrown his way, especially during one remarkable span of 115 consecutive games without a strikeout. He said the secret to making contact was simple: Keep your eye on the ball—“and it sure isn’t much of a secret, is it?” Sewell, like Ted Williams, insisted he could see his bat hit the ball.

In 1930, despite only three strikeouts all season, his batting average dipped to .289, and the Indians released him on January 20, 1931. The 32-year-old Sewell was out of work for all of four days. On January 24 the New York Yankees signed the infielder to play third base and assigned him to room with star first baseman Lou Gehrig. Sewell played well in pinstripes, batting .302 in130 games for the Yankees in 1931, but he dropped to .272 and .273 for the next two seasons, which was about average for that era. Still, he refused to give in to pitchers. In 1932 Sewell struck out only three times, a rate of 167.7 at-bats per strikeout, still the major league record. On September 24, 1933, Sewell played his final major league game. Four months later, the Yankees released him.

Sewell’s success, in retrospect, was improbable at best. The son of a doctor, he grew up in a family in which the expectation was that he would become a physician himself. He was undersized and spent only part of one season developing his skills in the minor leagues, yet his durability and batting eye were better than that of almost every other player in the history of the game. His career batting average was .312, and he used his 2,226 hits (of which only 49 were home runs) to drive in 1,055 runs, and he scored 1,141 times. His career mark of one strikeout per 63 at-bats remains an almost unassailable major-league record as of 2011.

Sewell was on the field for two of the most memorable moments in the annals of the game. On October 10, 1920, the 22-year-old Sewell was playing shortstop when Cleveland second baseman Bill Wambsganss recorded the only unassisted triple play ever in World Series play. Twelve years later, and now batting for the New York Yankees, Sewell was in the lineup with Babe Ruth when the Bambino hit his “called shot” off Charlie Root in Game Three of the World Series. Whether Ruth called his shot is still debated, but Sewell declared, “I don’t care what anybody says, he did it.”

After Sewell’s playing career ended at age 35, his life was just getting started. Always considered a quiet and compassionate person, he would return to Alabama often during the Great Depression, usually bringing bats and balls and baseball gloves to the children of Elmore County. Joe even tried coaching, accepting a position with the Yankees for the 1934 and 1935 seasons, but left the game to set up a hardware store in Alabama.

In 1952 Cleveland hired Sewell as a regional scout and in 1954 promoted him to Southeast scouting supervisor (a position in which he signed, among others, Jim “Mudcat” Grant). Joe also worked as a spokesman for a dairy manufacturer in Alabama. In 1962 he left the Indians organization, but the next season was back in the game as a scout for the New York Mets. The following year, 1964, brought Sewell home to stay.

Sewell’s alma mater, the University of Alabama, had established itself as a college football dynasty in the early 1960s under coach Paul “Bear” Bryant. The Crimson Tide baseball program, however, had waned, finishing just a game over .500 in 1963. In 1964 Joe replaced 25-year coach Tilden “Happy” Campbell as head coach, and for the next six seasons guided Alabama baseball teams to a 106-79, record, including a 24-14 mark in 1968 that won the Southeastern Conference championship. In 1970 Sewell stepped down from head coaching when he reached the mandatory retirement age.

Joe Sewell was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee in 1977, and one year later the University of Alabama rechristened its baseball stadium Sewell-Thomas Stadium in honor of Joe’s accomplishments. Today the field is simply called “The Joe.” His wife, Willie, passed away a few years later. Joe remained near his children and grand-children in Alabama, available to writers whenever they sought him.

On March 6, 1990, Joe Sewell passed away in Mobile, Alabama. He is buried at Tuscaloosa Memorial Park in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. In 2004 his native Elmore County established a scholarship, the Joe Sewell Memorial Award, for local high school seniors who exhibit moral character, Christian values, leadership, academic and athletic excellence. Twenty years after his death, the name of Joe Sewell is still associated with excellence and character.

Sources

Baseball-reference.com

Informal discussion with Joseph W. Lisenby, CAPT, USN; October 1996.

Honig, Donald. The October Heroes. Reprint, Bison Books, 1996.

Joesewellaward.org

Russell, Fred. “Joe Sewell: The Best Contact Hitter Ever.” Baseball Digest. September 1977.

Sowell, Mike. The Pitch That Killed. New York: Macmillan, Collier Books, 1989.

Thomas, R. “Joe Sewell, 91, Hall of Famer Who Set Fewest-Strikeouts Mark.” New York Times. March 8, 1990.

The Sporting News, various issues

Full Name

Joseph Wheeler Sewell

Born

October 9, 1898 at Titus, AL (USA)

Died

March 6, 1990 at Mobile, AL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.