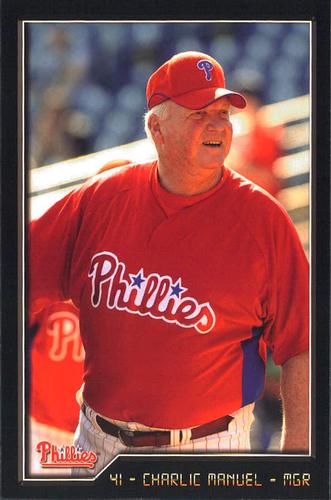

Charlie Manuel

We’re told from a young age not to judge a book by its cover. We’re also told you never get a second chance to make a first impression. With Charlie Manuel, outward presentation and first impressions often prove misleading.

We’re told from a young age not to judge a book by its cover. We’re also told you never get a second chance to make a first impression. With Charlie Manuel, outward presentation and first impressions often prove misleading.

“You hear his country accent, and you think he’s a little bit slow,” longtime Phillies shortstop Jimmy Rollins once said. “But he’s sharp as a tack.”1

Charles Fuqua Manuel was born on January 4, 1944, somewhere in southern West Virginia or the western part of Virginia. His official birthplace is listed as North Fork, West Virginia, but this is not quite accurate. “Evidently, I was born in a car and they took me to the doctor in North Fork,” Manuel said. “I never actually lived there, but, if you go online, I’m listed somewhere as their most prominent citizen.”2

Charlie was the third of 11 children (and first boy) born to Charles Fuqua Manuel Sr. and June Manuel. Charles Sr. was a Pentecostal preacher given his unique middle name by his mother after the doctor who delivered him.3 The Manuels settled into Buena Vista, Virginia, in the western portion of the state, where they struggled to get by. The family of 13 lived in a house with only three bedrooms. Despite young Charlie’s love of baseball, the Manuels couldn’t afford proper equipment, so he made his own. “I used to cut my own bat out from a stick,” he said. “I wanted something better than just a broomstick. I wanted to round it up top and make a handle.”4

Manuel was a four-sport star (baseball, football, basketball, and track) at Perry-McCluer High School in Buena Vista. He was recruited to play basketball by several colleges, including the University of Pennsylvania. Charlie probably would have taken Penn’s offer until his life changed dramatically two months before graduation. Manuel’s father took his own life inside the family’s home. He left Charlie, the oldest son, a note charging him with providing for the family. “I felt like all of a sudden I had a lot of responsibility on my hands,” Manuel said. “I felt like that someone had to work, someone had to provide for them, someone had to feed them, someone had to take care of them.”5

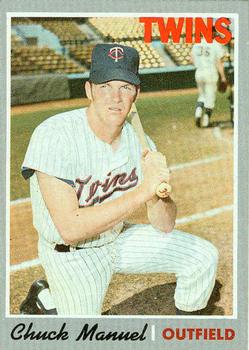

Feeling the need to provide, Manuel bypassed college and signed with the Minnesota Twins organization in 1963 for $20,000. He continued to send money home during the season and worked offseason jobs back home.

Manuel, then sometimes known as Chuck, began his professional career in 1963 near his home with the Wytheville (Virginia) Twins of the Appalachian League, hitting .358 with seven home runs in 58 games. From 1964 through 1966 he continued through the Twins organization, splitting time between Orlando and Wilson (North Carolina), hitting no higher than .265 with a total of 11 home runs over the three seasons.

As a 23-year-old in 1967, the powerful 6-foot4, left-handed-hitting Manuel established himself as a legitimate prospect. Playing for Wisconsin Rapids of the Midwestern League, Manuel surpassed the magic .300/.400/.500 mark (.313 batting average/.403 on-base percentage/.514 slugging percentage). After a successful campaign for Double-A Charlotte in 1968 (.283, 13 home runs, 79 RBIs) that saw him named a Southern League All-Star, Manuel was invited to spring training with the Twins in 1969.

Manuel was the star of the Twins’ 1969 spring training. Manager Billy Martin had no choice but to keep him on the team when it headed north for the season. The 25-year old made his major-league debut in the Twins’ 4-3 Opening Day loss at Kansas City on April 8, grounding out to second in the 12th inning against Moe Drabowsky. He got his first major-league hit in his first start, a double off the California Angels’ Tom Murphy, and cracked his first home run a week later against the White Sox’ Don Secrist.

At the end of May, Manuel was hitting .311 with a pair of home runs and was receiving regular playing time as a platoon player in the outfield. However, his production regressed in June, and his playing time did likewise in July. He hit a double against the Seattle Pilots on July 19, which turned out to be Manuel’s last hit of the season. From July 20 through the end of the season on October 1, he improbably went 0-for-36 and saw his respectable average of .258 crater to a final mark of .207 for the season.

As bad as his season was, it was the one in which he played in the most games and set career highs in virtually every counting stat.

Manuel played in 59 games for the Twins in 1970, but again found himself in the minors, seeing action in 21 games for Triple-A Evansville. Despite spending most of the season with the Twins, he started only six games all season, a startling departure from his more frequent playing time as a rookie in 1969.

After splitting time between the majors and Triple-A and playing in only 18 games for Minnesota in 1971, Manuel again spent the entire 1972 season with the Twins. He started 27 games, played in 63 overall, and scuffled his way to a .205 batting average and one home run in 129 plate appearances. He would never again spend significant time in the major leagues as a player.

Manuel spent the entire 1973 season with Triple-A Tacoma, then was part of a four-player deal that sent him to the Los Angeles Dodgers. He spent most of the next two seasons at Triple-A Albuquerque, batting better than .300, and topping.400 in on-base percentage and .600 in slugging percentage in each season. He finished in the top 11 of the Pacific Coast League in all three categories during both seasons, and his .601 slugging percentage led the league in 1975. He got into 19 games for the Dodgers in 1974-75, never starting a game. At age 31, he had played in his last major-league game.

Manuel spent the entire 1973 season with Triple-A Tacoma, then was part of a four-player deal that sent him to the Los Angeles Dodgers. He spent most of the next two seasons at Triple-A Albuquerque, batting better than .300, and topping.400 in on-base percentage and .600 in slugging percentage in each season. He finished in the top 11 of the Pacific Coast League in all three categories during both seasons, and his .601 slugging percentage led the league in 1975. He got into 19 games for the Dodgers in 1974-75, never starting a game. At age 31, he had played in his last major-league game.

Though his career as a player in the major leagues was over, Manuel was not done playing. He was just entering the most prominent phase of his playing career, not in the United States but in Japan.

He signed with the Yakult Swallows of Tokyo for the 1976 season. The team flew him into town, gave him an interpreter, and called a press conference — hardly the welcome expected for a .198 hitter in the major leagues. “I was kinda petrified,” Manuel said of the welcome. “They had my [jersey] number. I was already a star before I ever got there. They were talking about how good I was. I thought, ‘You gotta be kidding me.’”6

Despite his foreboding, between 1976 and 1981, Manuel terrorized pitching in Japan’s Central League, hitting .303 with 189 home runs and 491 RBIs for the Swallows and the Kintetsu Buffaloes. His .324 average, 37 home runs, and 94 RBIs for Kintetsu in 1979 earned him the league MVP, the first American player to be so honored. He followed up his MVP season by slugging 48 home runs for the Buffaloes in 1980, which long stood as a record for an American player in Japan. Manuel played for two pennant-winning teams in his six seasons in Japan. His power at the plate and his reddish hair earned Manuel the nickname Aki Ono (Red Devil) among the fans and players in Japan.

Manuel’s playing career ended after the 1981 season, and he wasted little time getting involved in the game on the other side of the white lines. He spent the 1982 season as a scout for the Twins. In 1983 Manuel was back on the field, taking over as the manager of Wisconsin Rapids, the Twins’ entry in the Class A Midwest League, and one of the teams he had played for on the way up to the majors. Just as he had done as a player in the ’60s, Manuel began climbing up the Twins organization as a manager. He managed Double-A Orlando in 1984 and ’85, then took over the Twins’ Triple-A outposts in Toledo and Portland in 1986 and 1987.

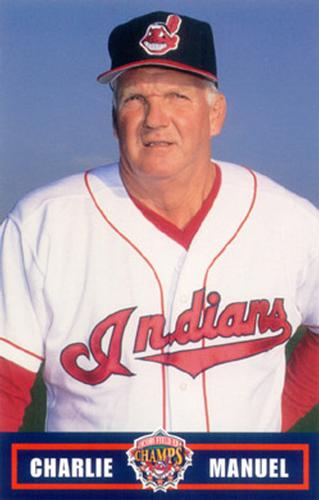

Manuel joined the Cleveland organization in 1988 as the Indians’ hitting coach. He held this role for two seasons before returning to the minors as a manager in 1990, just as the team was building the nucleus that would power it to two World Series appearances in the 1990s. The Indians of the ’90s were paced by a powerful offense, and the principal members of the attack — Albert Belle, Carlos Baerga, Manny Ramirez, Jim Thome, et al. — all played for Manuel in his four seasons as manager of Cleveland’s Triple-A teams at Colorado Springs and Charlotte. In 1992 Colorado Springs won the Pacific Coast League title, and Manuel took home the league’s Manager of the Year honors. He followed that up in 1993 by leading Charlotte, the Indians new Triple-A affiliate, to the International League crown.

In 1994 Manuel returned to the majors for his second stint as Cleveland’s hitting coach. By now these Indians were talented and ready to win. After finishing one game out of the division lead in the strike-shortened 1994 season, the team won five straight AL Central titles from 1995 to 1999, posting three of the top five-win totals in team history. The run was highlighted by 100 wins in 144 games in 1995, when Cleveland won the Central Division crown by 30 games. The 1995 and 1997 editions both captured the American League pennant before falling in the World Series.

Manuel oversaw a powerful offense that bludgeoned teams with its run-scoring prowess. The top three run-scoring teams and the top six home-run-hitting teams in Indians history all came under Manuel’s watch as hitting coach and his subsequent run as manager.

While watching your powerful lineup pound opposing pitching is fun, not everything was fun during Manuel’s time in Northeast Ohio. After suffering a heart attack in 1990, he had another in 1998 that necessitated a quadruple bypass. In 2000 Manuel was diagnosed with diverticulitis, which caused a pouch in his colon to rupture. During the ensuing surgery, doctors discovered that he had kidney cancer. He ended up managing from the bench with a colostomy bag under his uniform for about a month. “That might have been the lowest point I’ve ever been in my life,” he recalled years later. “I was pretty much sick that whole summer.”7 Then early in the 2001 season Manuel grew ill while throwing batting practice. Scar tissue had grown over his small intestine, his gall bladder needed to be removed, and his body had filled with infected fluid. The incident required Manuel to remain on IV fluids for nearly four months to allow the fluid to continue draining.

“(His health history is) one of the reasons why his tolerance for people to go on the DL is not very high,” said Ruben Amaro Jr., who was assistant general manager and then GM during Manuel’s time in Philadelphia.8

Manuel replaced Mike Hargrove as Indians manager in 2000. The Indians continued to score runs but could not match the overall success of the Hargrove years. A Central Division title in 2001 was bracketed by playoff misses in 2000 and 2002. Unable to come to terms with him on a contract extension, the Indians fired Manuel as manager in July of 2002.

Manuel replaced Mike Hargrove as Indians manager in 2000. The Indians continued to score runs but could not match the overall success of the Hargrove years. A Central Division title in 2001 was bracketed by playoff misses in 2000 and 2002. Unable to come to terms with him on a contract extension, the Indians fired Manuel as manager in July of 2002.

After the 2002 season, one of Manuel’s prized protégés, Jim Thome, left the Indians and signed as a free agent with the Phillies. Unattached after more than a decade with the Cleveland organization, Manuel followed Thome to Philadelphia, taking a job as a special assistant to Phillies GM Ed Wade.

The signing of Thome raised expectations in Philadelphia higher than they had been in a decade. After consecutive nonplayoff seasons in 2003 and 2004, manager Larry Bowa was fired and Manuel succeeded him.

Perhaps born of its tendency to be overlooked halfway between New York City and Washington, Philadelphia boasts a rougher edge than its sophisticated mid-Atlantic neighbors. It may lack the financial power of New York or the political power of Washington, but one thing no city can top is Philadelphia’s embrace of its four major sports teams. The day after the Phillies announced Manuel’s hiring, Rob Maadi of the Associated Press presciently wrote, “Charlie Manuel’s thick Southern drawl, down-home charm and folksy nature make him an odd fit for gritty Philadelphia. He’ll be a perfect choice as manager if he leads the Phillies to the playoffs.”9

“I came here to do a job,” Manuel said at his introductory press conference. “It’s a we, not an I. And we’re going to get the job done. Our goal is to get to the World Series and win it. That’s what we’re going to do.”10

The fans were unsure what to make of Manuel. His stuttering and malaprops left them uninspired. His occasional mistake in executing a double switch left the fans confused. The team again narrowly missing the playoffs in 2005 and 2006 left the fans frustrated, and the folksy manager was an easy target. Many in the fan base and media called for Manuel’s ouster.

Lost in the disappointment of 2006 was a changing of the guard in Philadelphia. Longtime stalwarts like Bobby Abreu, Mike Lieberthal, and David Bell were either shipped out or saw their roles diminished. Ryan Howard, Jimmy Rollins, and Chase Utley emerged as three of the elite players in the National League, and ace left-handed pitcher Cole Hamels made his debut. The team was given a winning attitude and hard-nosed grit in the acquisition of World Series champion center fielder (2005 White Sox) Aaron Rowand, who, in contrast to the timid fielding Abreu, literally broke his face chasing down a fly ball in a May game. The complacent, good but not good enough attitudes and players that dominated the Phillies for years had been replaced by a group of gritty gamers. The passion of the group on the field matched the passion in the stands, and the common thread among these players was that they loved playing for Charlie Manuel. “He not only brought the best out of myself, but he brought the best out of a lot of players,” Utley said.11

The Phillies’ young core of stars bore a striking resemblance to the 1990s Indians teams Manuel had been a part of, and the 2006, 2007, and 2009 editions led the NL in runs scored, while the 2008 team tied for second.

Before the 2007 season Jimmy Rollins declared his team the team to beat in the National League East. The Phillies hadn’t been to the playoffs since 1993. Things did not start well. By April 20 the Phils were already 6½ games out of first place and Manuel had gotten into a heated postgame verbal altercation with a local media personality. The pitching staff struggled, but the offense kept the Phillies in view of a playoff spot. The Phillies trailed the New York Mets by six games in the East in late August when the two teams squared off in a four-game series in Philadelphia. The Phillies swept the four-game set, including two walk-off wins, the finale a wild 11-10 triumph that shrank the Phillies’ deficit to two games.

A cold streak after the Mets series left the Phillies seven games behind with 17 to play. But they beat the Colorado Rockies and then swept the Mets over the next four games. They finished on a 13-4 tear while the Mets never recovered from their second consecutive sweep by the Phillies and stumbled to a 5-12 finish that allowed the Phillies to win the NL East on the last day of the season. Even though the Phillies were swept out of the National League Division Series, the team had gotten over the hump and the core of young stars provided hope to a fan base that hadn’t seen a major championship in nearly 25 years.

The 2008 season followed a pattern similar to 2007. The team struggled out of the gate, hung around first place on the strength of a powerful offense, and found itself 2½ games behind the Mets with 17 left to play. The Phillies once again finished 13-4 and finished three games ahead of the Mets to win their second straight division title. After dispatching the Milwaukee Brewers in four games in the NLDS, Philadelphia defeated the Los Angeles Dodgers in five games in the NL Championship Series to win its first pennant since 1993. The victory was bittersweet for Manuel, whose mother, June, died before Game Two of the NLCS. He stayed with the team through the end of the series before traveling to Virginia for her service. Manuel later told reporters that his mother was a huge fan of his team and that he put a Phillies hat in her casket.12

Just as in their first two postseason series, the Phillies lost only once in clinching their first World Series since 1980, a defeat of the Tampa Bay Rays. Weather became a prevailing storyline in the series, delaying the start of Game Three for several hours and causing a two-day stoppage in the middle of Game Five. But when Phillies closer Brad Lidge struck out Tampa Bay’s Eric Hinske to end it, Manuel’s declaration that the Phillies were going to win the World Series under his watch came true.

As the on-field party celebrating the victory unfolded, Manuel was interviewed on the field by Fox Sports. As he answered questions, the ballpark chanted a chorus of “Charlie! Charlie!” Grabbing the microphone from interviewer Jeanne Zelasko, Manuel addressed Phillies fans everywhere, bellowing in his Southern drawl “Hey listen! … This is for Philadelphia! … This is for our fans! … Hey! … Who’s the world champions!?!”

The bumbling manager had become a folk hero to the fans of Philadelphia.

As an encore, the 2009 team again won the National League pennant but could not overcome the New York Yankees in the World Series. The 2010 and 2011 seasons saw two more division titles, running the Phillies’ streak, echoing the Indians of the ’90s, to five in a row. Injuries and age kept the Phillies from competing in 2012 and 2013, and in mid-August of 2013 Manuel was fired. He managed his last game knowing that he was about to be removed.

Manuel left the Phillies with exactly 1,000 wins as a major-league manager, two pennants, and a World Series title. As of 2018 he was the winningest manager in the Phillies’ long history; his 780 wins were more than 130 ahead of second-place Gene Mauch. Of the 49 postseason wins the Phillies registered between 1883 and 2011, 27 of them came under Manuel’s stewardship.

Manuel has two adult children from a previous marriage and considers the three children of his longtime girlfriend Missy Martin as his own as well. After living near his roots in Virginia for many years, as of 2015 he made his home in Winter Haven, Florida.

After leaving the Phillies dugout, Manuel was given the title of senior advisor to the general manager. In 2014 he inducted into the Phillies Wall of Fame.

“I know how lucky I’ve been, how fortunate about how long I’ve gotten to be in the game that I love,” he said of his career in baseball. “All the people that I’ve met, all the places that I’ve been. I look at that, and I can’t even put into words how I feel about it.”13

Last revised: November 12, 2018

This biography was published in “1995 Cleveland Indians: The Sleeping Giant Awakes” (SABR, 2019), edited by Joseph Wancho.

Notes

1 Editorial, “Charlie Manuel: An Appreciation.” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 23, 2013.

2 Doug Doughty, “Favorite Son Returns Home,” Roanoke.com, October 24, 2013.

3 Victor Fiorillo, “One of Us: Charlie Manuel,” Philadelphia Magazine, May 2014.

4 Mandy Housenick, “No Easy Journey: Charlie Manuel Overcame Myriad of Challenges in Reaching Pinnacle of Career,” Allentown (Pennsylvania) Morning Call, October 16, 2010.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Rob Maadi, “Manuel Hired to Manage Phillies,” USAToday.com, November 3, 2004.

10 Ibid.

11 Editorial, “Charlie Manuel: An Appreciation,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 23, 2013.

12 Joe Juliano, “Manuel’s Mother Knew the Phillies,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 19, 2008.

13 Bob Ford, “For Phillies’ Charlie Manuel, Another Year Begins in a Long Baseball Career,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 11, 2013.

Full Name

Charles Fuqua Manuel

Born

January 4, 1944 at Northfork, WV (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.