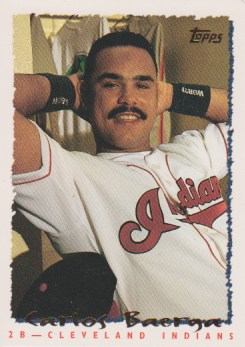

Carlos Baerga

In just his third season in the major leagues, Carlos Baerga was a leader on the field. The Cleveland Indians second baseman broke into the big leagues as a third baseman in 1990. But he was moved to second, where he found a home. There was never a question about Baerga’s ability to hit. He collected 205 hits in 1992, including 32 doubles and 20 home runs, and produced 105 RBIs. Those numbers added up to a .312 batting average and his first selection to the All-Star Game.

In just his third season in the major leagues, Carlos Baerga was a leader on the field. The Cleveland Indians second baseman broke into the big leagues as a third baseman in 1990. But he was moved to second, where he found a home. There was never a question about Baerga’s ability to hit. He collected 205 hits in 1992, including 32 doubles and 20 home runs, and produced 105 RBIs. Those numbers added up to a .312 batting average and his first selection to the All-Star Game.

But on March 23, 1993, Baerga stepped outside the white lines to become a leader of the club off the field. The day before, the Indians were given a day off by manager Mike Hargrove. Their spring training was held in Winter Haven, Florida. The players took advantage of the free day. Some groups took their families to Disney World, others went to Universal Studios. Others stayed closer to the spring-training complex.

Tim Crews came over to the Indians via free agency from Los Angeles to Cleveland. He owned a ranch close to Winter Haven, and invited the team to his home for a picnic. Steve Olin and Bob Ojeda took Crews up on his offer. Toward the end of the day, Crews, Ojeda, and Olin climbed into Crews’ 18-foot bass boat, and circled around Little Lake Nellie. Indians trainer Fernando Montes observed the trio from where the boat departed. A neighbor’s dock, which extended more than 50 yards, sat on the far side of the lake. As Crews accelerated, the front of the boat rose up, blocking their vision. As soon as the boat planed out, it was now the under the dock. It was too late. The accident occurred in three feet of water. “We heard this loud thump and a crash,” said Montes. “And it was silence, utter silence. I knew without any hesitation that Steve Olin had passed.”1 Crews was also dead and Ojeda was badly injured.

The next day, Cleveland’s vice president of public relations, Bob DiBiasio, was looking for a player who would talk to the media about the boating tragedy. “Everybody on the team was in tears,” said DiBiasio. “Nobody wanted to step forward and discuss what happened.”2 Carlos Baerga stepped forward, volunteering to be the team spokesman. “I was brokenhearted,” he said, “but I had a responsibility to the two good people we had lost. They were part of my life. I told God, ‘Give me words, because I know it’s going to be hard for me.’”3

Carlos Obed Baerga was born on November 4, 1968, in Santurce, Puerto Rico. He was the oldest of four children born to José and Baldry Baerga. José worked in the credit office of Puerto Rico’s largest newspaper, El Nuevo Dia. José managed Carlos’s little league teams. At 8, Carlos was holding his own against boys 10 to 12 years old. When he reached 14, Baerga was mixing it up on the diamond with adult amateurs in their 20s and 30s in the Puerto Rican Double A League. When Baerga reached 16, he was playing in the winter leagues against major leaguers.

“I remember my father saying, ‘Don’t come back home if you don’t have your uniform dirty,’ Baerga once recalled. “Ever since, I have put it in my mind to play hard. He always pushed me. My father always watches me, he’s always behind me.”4

Longtime Indians bullpen coach Luis Isaac (1987-2008) watched Baerga grow in his native Puerto Rico. “I knew right away he’d be a big-league player,” said Isaac. “Even when he was little, he was the type of kid who wanted to play two games a day. He’d be telling the other kids on the field what to do. He always played with that kind of intensity.”5

José worked with his son on becoming a switch-hitter so that he could play every day no matter who the pitcher was. Carlos, a natural left-handed hitter, worked hard to sharpen his skill from the right side of the plate. “I’ve still got to practice it every day,” he said in 1995. “But it has helped me. I see a guy like Randy Johnson pitching and I can’t imagine having to face him left-handed. The same goes for David Cone and facing him right-handed.”6

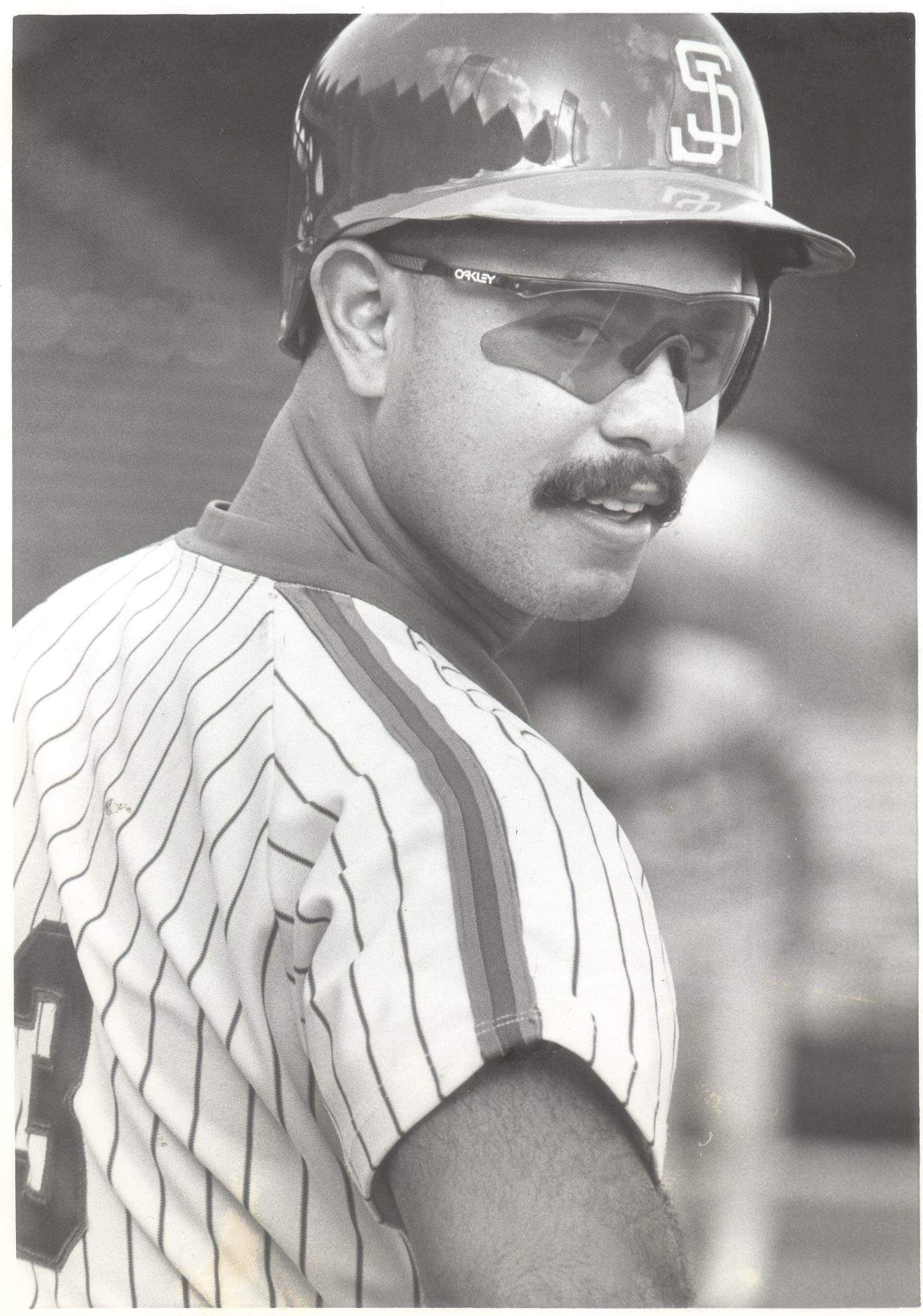

Word of Baerga’s ability spread around the island, and soon professional scouts arrived to get a look at the 14-year-old. Luis Rosa, a scout for the San Diego Padres, got Baerga to sign for a $65,000 bonus in 1985, when he turned 17 years old. (Rosa had a keen eye for talent. At the time Baerga signed, 32 of Rosa’s players had made their way to the big leagues.

Although Baerga seemed destined for big-league stardom, there was one problem. The Padres already had a second baseman in-waiting, Roberto Alomar. Baerga started his playing career at Class-A Charleston in the South Atlantic League. “They asked me to take him with me and when (rookie level) Spokane opened up (in mid-June) he’d go there,” said Charleston manager Pat Kelly.7 Baerga, who did not speak English that well, would ask Kelly, “Coach, why me no play?” Kelly would explain to Baerga that he had to play his more experienced players. Baerga would nod, as if he understood, but he returned the next day, asking the same question. This went on for about a week. “Finally, I put him in as a pinch-hitter, and he got a hit, of course,” said Kelly. “So I started him the next day, and he went like 4-for-4, and they were all (line drives). So he stayed with us the whole year.”8

Baerga showed that he could handle the bat on the minor-league level. He was still somewhat raw, but he was still just a teenager in his first three years in the minors. Because Alomar was the second baseman of the future for the Padres, it became evident that a new position would have to be found for Baerga, even though he felt the most comfortable at second base.

When Baerga reported to Double-A Wichita in 1988, he was switched to shortstop. In 1989 he was promoted to Triple-A Las Vegas and was placed at third base. Although he made 32 errors while manning the hot corner for Las Vegas, Baerga was in the lineup to hit. He hit .275 with 28 doubles, 10 homers, and 74 RBIs. He was somewhat of a free swinger, and his strikeouts easily tripled his walks.

The Cleveland Indians were shopping outfielder Joe Carter at the 1989 winter meetings. Carter’s contract was up in 1990, and the Indians knew they would not be able to re-sign him. Carter made no secret of his desire to leave the Indians, preferably to a contender, and a lucrative contract would also be nice.

The Indians found a suitor in the Padres. The teams dickered over whom the Padres would send the Indians’ way for the star slugger. The Indians insisted that Baerga be included in the deal. The Padres viewed Baerga as their third baseman of the future. But the Indians’ persistence won out, and they received Baerga, catcher Sandy Alomar Jr. (Roberto’s brother), and outfielder Chris James for Carter. “I managed against Carlos in the Pacific Coast League in 1989,” said Mike Hargrove. “On my report at the end of the year, I recommended that we should try to acquire him. So did my coaches, Rich Dauer and Rick Adair.”9

The Indians hired John McNamara to manage in 1990. Cleveland was putting together a solid nucleus of young talent, and it began with Baerga and Alomar. The two newcomers were blended with Albert Belle, Cory Snyder, Jerry Browne, and Brook Jacoby. Tom Candiotti, Greg Swindell, and Buddy Black anchored the starting rotation.

Alomar was a star right away. He was named the starting catcher on the 1990 AL All-Star team, won the Gold Glove, and was voted Rookie of the Year. Baerga would have to wait a bit for his time to come. Browne was entrenched at second base and Jacoby manned third. The Indians had signed Keith Hernandez to play first base. But Hernandez suffered through various injuries and played in only 42 games. His injuries offered the break that benefited Baerga; Jacoby moved to first base and Baerga became the new third baseman. “From the time he got to Cleveland, Carlos was the heart and soul of the Indians,” said batting coach José Morales. “We sent him down to Triple A for two weeks in his rookie year, and team spirit just sank. When he came back, it was like a kid returning to his family. He brings an energy, a unity to the team.”10

Baerga hit .266 his rookie season. On September 20 at Yankee Stadium, the 5-foot-11, 165-pound infielder went 4-for-5 with three doubles (a career high) and a triple with three runs scored and three RBIs. The barrage came the day after his first child, a daughter, was born. “Baerga is a hitting machine and maybe his wife should have a baby every night,” said McNamara.11 Although the Indians finished with a 77-85 record, they found themselves in fourth place in the AL East. It was something to build on for the young Tribe.

Indeed, Baerga’s enthusiasm for the game was unbridled and was contagious. He was a fan favorite for his all-out hustle. But in his second season, the Indians proved unable to build on the success from 1990. McNamara was fired (Hargrove replaced him) and the team topped 100 losses.

But the pieces were beginning to come together. Charles Nagy became the leader of the pitching staff. Kenny Lofton was acquired from Houston to solidify center field and bat leadoff. Paul Sorrento was acquired from Minnesota to provide a left-handed bat and he was an above-average first baseman. The Indians worked to sign Belle, Alomar, Nagy, Belle, Lofton, and Baerga to long-term deals, selling them on the talent of the core team.

Baerga made their investment pay off. In back-to-back seasons (1992 and ’93) he hit more than 20 home runs, drove in more than 100 runs, and batted over .300. He was the first second baseman to achieve these numbers in consecutive seasons since Rogers Hornsby turned the trick in 1921 and 1922.

Baerga entered the record books on April 8, 1993. He hit two home runs in the seventh inning against the New York Yankees, one from each side of the plate. He connected off Steve Howe for a two run-shot, then hit a solo home run off Steve Farr. The Indians scored nine runs in the inning on their way to a 15-5 victory. “It’s exciting,” said Baerga. “They told me I set a record when I got back to the dugout after the second homer, but I didn’t believe them. When I got to the clubhouse after the game, Bobby DiBiasio, our public-relations man, told me I’d set a record.”12 Baerga’s record night did not surprise Hargrove. “The beauty about him is that there’s no way to pitch him. He hits to all fields,” the manager said.13

Baerga made the All-Star Game for the first time in 1992 and repeated in 1993. The Indians finished with identical 76-86 records in both seasons.

Baerga made the All-Star Game for the first time in 1992 and repeated in 1993. The Indians finished with identical 76-86 records in both seasons.

In 1994 the Indians said goodbye to Cleveland Stadium and relocated to the new Jacobs Field, across downtown. The baseball-only venue was a boon for the Tribe. The Indians had brought in veteran leadership in the offseason, signing Eddie Murray and Dennis Martinez. They traded for shortstop Omar Vizquel. Manny Ramirez and Jim Thome arrived through the farm system. The results were favorable. The Indians were one game behind Chicago in the new AL Central when the season ended on August 12 because of the players strike. Although the development was a big disappointment to Tribe fans, baseball fever had indeed returned to the North Coast.

The strike wiped out the 1994 postseason and bled over into the 1995 season. Baerga finished the 1994 season with 19 home runs, 80 RBIs, and a .314 batting average.

After play resumed in late April of 1995, Cleveland broke through its 41-year stretch of not appearing in a postseason game. The Indians won 100 games and Baerga, batting third in the potent Cleveland lineup, was third on the team with 90 RBIs. He batted .314. Cleveland swept Boston in the ALDS and topped Seattle in six games in the ALCS. The Indians met the Atlanta Braves in the World Series. The old adage that good pitching will defeat good hitting proved accurate, as the Braves captured the world championship in six games.

Baerga hit .400 in the ALCS and drove in four runs in both the ALCS and the World Series. He knocked in the first two runs in the Indians’ 5-2 victory in Game Two of the ALDS and three runs in their 7-6, 11-inning Game Three win in the World Series. All told, he hit .292 in the 1995 postseason.

The one constant in Baerga’s career to this point was his desire to play winter ball in his native Puerto Rico. He was lauded by Puerto Rican fans for his work in the community as well as his work on the diamond. He often held clinics and his enthusiasm for the game was infectious. “They won’t even let you take batting practice,” Baerga said, referring to the young fans. “They come right onto the field for autographs.”14

Baerga was also a fan favorite in Cleveland. His all-out effort between the lines and his effervescent personality off it endeared him to hard-working, blue-collar town. Thus the backlash the Indians front office received when they traded Baerga on July 29, 1996, was not unexpected. The Indians swapped Baerga and utility infielder Alvaro Espinoza to the New York Mets in a trade-deadline swap for infielders Jeff Kent and José Vizcaino. Baerga’s numbers were on the downside (10 home runs, 55 RBIs, .267 batting average) through 100 games. The Indians cited Baerga’s weight gain. (He was said to have been 20 to 25 pounds overweight in spring training.) His work ethic and priorities were also questioned by the Indians brass. Baerga suffered a slight fracture in his right ankle and played in only about 10 games in the winter league. He used the winter league to stay in shape, hence the weight gain. He was also battling a badly sprained left wrist and a strained groin.

“When you get close to the trading deadline, you never know what’s going to happen,” said New York GM Joe McIlvaine. “To be honest, when they dropped Baerga’s name, I was a little surprised. I thought, ‘Here’s a chance to get a good, quality player.’ And we did it. I don’t think a year ago we could’ve acquired Carlos Baerga.”15

The presence of second baseman Edgardo Alfonzo on the Mets created a question of where Baerga would be stationed. As it turned out, an abdominal strain limited Baerga to 26 Mets games, mostly at first base, and a.193 batting average.

Bobby Valentine took over for Dallas Green as the Mets manager with a month to go in the 1996 season. Over the next two seasons, Baerga recaptured his second-base spot. Alfonzo was moved to third. Manager Valentine, who at times could be as subtle as a sledgehammer, would comment about Baerga’s approach to hitting as “an embarrassment.”16 Baerga felt the pressure to produce, feeling that he needed to prove his worth every day. But he did not have a strong lineup like the one in Cleveland to back him up. His batting average was .274 over the 1997 and 1998 seasons, but his power numbers were dismal. The ball was not jumping off his bat as it once had.

One longtime major-league executive explained Baerga’s decline this way: “Carlos is a God-given good hitter, and sometimes a player like that takes a lot for granted, doesn’t stay on top of his physical conditioning and mental preparation. And there’s no doubt in my mind that is what happened to him. I mean, he’s always had a thick body, but last year, well, he just got plain heavy. I think it’s all related (to his weight and conditioning). I was really surprised the Mets took him. No … I was shocked.”17

The Mets did not pick up Baerga’s option year in 1999. The rest of his career was a composite of being signed, being waived, and riding the bench. St. Louis signed him for the 1999 season, but waived him at the end of spring training. Cincinnati signed Baerga, but sent him to Triple-A Indianapolis before the season, and released him after two months. In a bit of déjà vu, San Diego signed Baerga, and then traded him back to the Indians for the balance of the 1999 season.

Baerga signed on with Tampa Bay for 2000, but his contract was voided before the season began. He signed with Seattle for 2001, but was released before the start of the season. He bided his time in independent leagues and for Samsung in the Korean League. Baerga eventually made his way back to the big leagues as a role player with Boston (2002), Arizona (2003-2004), and Washington (2005). After the 2005 season Baerga retired with a lifetime batting average of .291, 1,583 hits, 134 home runs, and 774 RBIs.

Baerga worked for ESPN as a Spanish-language broadcaster. He also helped coach the Puerto Rican National Baseball team. He also became the owner of the Bayamon Cowboys in the Puerto Rican Winter League.

Baerga married the former Miriam Cruz. They had two children, Karla and Carlos. In 2013 Baerga was inducted along with former Indians GM John Hart into the Cleveland Indians Hall of Fame. As of 2016 he was an ambassador for the Indians, making community appearances and spreading good will.

In 2016 Baerga threw out the first pitch in Game Two of the World Series at Progressive Field. He was, of course, cheered enthusiastically as he threw a perfect pitch to home plate.

Last revised: June 1, 2018

This biography appeared in “Puerto Rico and Baseball: 60 Biographies” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Edwin Fernández. It also appears in “1995 Cleveland Indians: The Sleeping Giant Awakes” (SABR, 2019), edited by Joseph Wancho.

Notes

1 ESPN, Outside the Lines, “Indians Boating Tragedy,” March 18, 2003. espn.com/page2/tvlistings/show155_transcript.html.

2 Frank Lidz, “Slick With the Stick,” Sports Illustrated, April 5, 1994: 66.

3 Ibid.

4 Rick Lawes, “Baerga Has Big Talent,” USA Today Baseball Weekly, January 13-26, 1993: 4.

5 Paul Hoynes, “Rock Solid: Carlos Baerga Is Part of the Foundation on Which the Indians Built a Winning Club,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 3, 1995: 8-D.

6 Ibid.

7 Lawes.

8 Ibid.

9 Hoynes, July 3, 1995: 9-D.

10 Lidz.

11 Russell Schneider, “Tribe Rolls to Victory,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, September 21, 1990: 1-E.

12 Paul Hoynes, “Baerga’s Blasts Rip Yankees: Two-HR Inning Sets Mark,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 9, 1993: 1C.

13 Ibid.

14 Lidz, 64.

15 Ray McNulty, “Net Heist Brings Baerga,” New York Post, July 30, 1996.

16 Buster Olney, “Benching Doesn’t Sit Well With Baerga,” New York Times, April 23, 1997: B11.

17 Michael P. Geffner, “The Sound and the Fury,” The Sporting News, May 5, 1997: 18.

Full Name

Carlos Obed Baerga Ortiz

Born

November 4, 1968 at Santurce, (P.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.