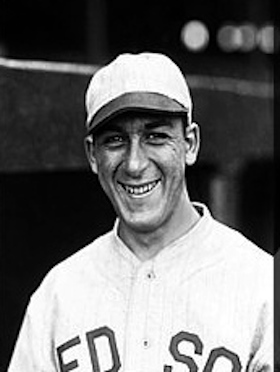

Pat Simmons

Right-hander Pat Simmons pitched for the Boston Red Sox in 1928 and 1929, appearing in 33 games with a career 3.67 earned run average, but never winning a game. He was charged with two losses.

Right-hander Pat Simmons pitched for the Boston Red Sox in 1928 and 1929, appearing in 33 games with a career 3.67 earned run average, but never winning a game. He was charged with two losses.

His surname was Anglicized. Unlike his contemporary namesake Al Simmons, who had been born as Aloys Szymanski, Pat Simmons was of Italian ancestry and had been born as Patrick Clement Simoni. Joseph, his father, was a moulder who had arrived in the United States in 1898. His mother Anna was a New York native, but born to two Italian parents. Patrick had three siblings–Frank, Rose, and younger brother Joseph.

He was born on November 29, 1908, in Watervliet, Albany County, New York. Patrick hadn’t spent much time in school. He attended P.S. No. 7 in Watervliet, but left shortly before finishing eighth grade. The month after his passing, his second wife, Mabel Simmons, explained: “His main avocation was Art, painting and designing and creating. Since he was a very little boy in school. He really had no interest in the 3-Rs school work, but his teacher who had such a keep perception of his ability, allowed him to draw on the blackboard and encouraged this talent.”1

Mrs. Simmons said that by the age of 15 he was running his own sign shop.

There was evidently time for baseball, too.

The youngster pitched for the Salem Witches in the Class B New England League in 1927, with a record of 11-11 despite an excellent earned run average of 2.03. The Red Sox purchased his contract on August 5, 1927, and Simmons was expected to report to the ballclub after the end of the New England League season. Sportswriter Ernest J. Lanigan recognized him as “the New England league’s leading shutout pitcher.”2 One of his better games was the 5-0 three-hitter against Lynn which included him making a “spectacular diving catch” which he converted into an unassisted double play.3 He pitched another three-hitter against Portland on August 25.

Simmons was one of four teenagers the Red Sox took to spring training at Bradenton, Florida in 1928. Though he lost a fair amount of time due to illness in camp, he recovered in time and made the team. He was possibly still growing. The Boston Globe described Simmons as “spare as to size, but apparently long in ability.”4 But his major-league listing is 5-feet-11 and 172 pounds.

In his April 18 debut, Simmons shone. The Red Sox were hosting the Yankees at Fenway Park. The first Sox pitchers (Herb Bradley and Jack Russell) each gave up five runs and the Yankees had a 10-2 lead. Manager Bill Carrigan asked Simmons to relieve. He worked 3 1/3 innings, and allowed just one hit–to the first batter he faced. He walked three and struck out two. It was more than three weeks before he got into another game. This time only eight runs were charged to the two pitchers who preceded him. Simmons pitched 3 2/3 innings and gave up one unearned run. That came about when he again put the first batter he faced on base–he hit White Sox right fielder Bill Barrett. On base now, Barrett advanced to second on an out, stole third base, and then scored when catcher Johnny Heving‘s throw to third went right past the bag into left field.

Twenty days later, he got into his third game. The same pattern held. The Athletics had already scored nine runs, off two Red Sox pitchers, when Simmons came in. He worked three innings with just one hit and no runs. In fact, over the first eight games in which Simmons appeared (only one of which the Red Sox won), working a total of 18 2/3 innings, he gave up zero earned runs.

That couldn’t continue forever. Finally, on June 30–more than two months after he’d first pitched, Simmons got tagged with an earned run–two of them, as the Yankees swept a doubleheader at Fenway. It wasn’t as though he’d been hit hard; he didn’t give up a hit at all. He faced two batters to open the seventh, walked them both and was removed only to see baserunners score off of Ed Morris, the man who took his place.

Despite twice getting tagged for four earned runs in the next few weeks, Simmons still–after his first 16 appearances–had a 2.52 ERA. Carrigan gave him a chance to start, against the Indians in Cleveland on July 25. He lasted only one inning, was charged with four runs on two bases on balls and four base hits, and took the loss.

Over his next six relief appearances, and 11 2/3 innings, he gave up just one earned run. He got another start, a full month after the last one. The Red Sox won the game–a rare event in 1928–but Simmons was gone after 3 1/3. He’d given up three runs.

One disastrous relief effort–six runs in three innings–marred September. His third and final start came on September 24. He pitched six innings against the Tigers, and gave up eight runs, six earned, while the Red Sox scored none. He took the loss in that one. The Boston Globe was particularly harsh: “When Simmons, who started for Carrigan, reached the seventh inning he had nothing to offer that the Tigers could not hit blindfolded, and after three men in succession had tripled he was relieved by Merle Settlemire.”5

Simmons was 0-2 in his first year, with a 4.04 ERA. That was still significantly better than the Red Sox team average of 4.39. The Red Sox finished deep in last place, with a 57-96 record. Perhaps he was better suited to relief work than starting. If one were to pull out his three starts, he was 0-0 with a 3.26 ERA. Simmons was still 19 years old.

Though Simmons was with the Boston club into early May of 1929, he was sent to Pittsfield on May 3, on option, and spent the full Eastern League season with the Hillies, getting in 253 innings of work and posting a record of 15-14 with a 4.91 ERA. Perhaps the Red Sox could have used him; perhaps it was better for him to get the additional experience. The Red Sox ERA was marginally worse than in 1928, having edged up to 4.43. The team won one more game but was still in last place with a 58-96 record.

After the minor leagues had closed up shop, Simmons did get a couple of shots at the end of the American League season. He pitched four innings against the Yankees on September 24, allowing three hits and no runs, and three more innings in Washington on October 6, again with three hits but no runs. That gave Simmons an ERA of 0.00 and brought his career number down to 3.67.

Simmons did go to spring training with the Red Sox in 1930. There were a couple of comments that indicated he might not have had the fire and determination to compete at the highest levels. In 1929, the Boston Herald had written that he “may be seen in relief roles, unless something happens to fan his ambition” and in 1930, noting that he took on “superfluous weight” very easily, added that he “certainly has a chance to become a regular if he will only bestir himself a mite. There is no pitcher on the staff who has more stuff. He has a fast one that whistles as it passes by and his curve makes the most of them say zu zu to the grocery man.”6

There was some disagreement with new Red Sox manager Heinie Wagner and Simmons was sent home in early April. They “did not get along well together,” wrote the Springfield Republican.7 The Red Sox released him to Pittsfield on April 9.

In 21 games, Simmons was 8-8 (3.37 ERA) for Pittsfield, though he also pitched in the Class B Three-I League at Quincy, Illinois (4-4, 5.85) and appeared in four games for Indianapolis. The Red Sox brought Simmons to spring training again in 1931 but he again split the season among three teams–Chattanooga, Nashville, and Montreal. All told he was 9-21 that season. In 1932, Simmons played in 32 games for Nashville (4-4, 3.74), but he also lost his first wife–the former Margaret Miller–to death that year.

His last year in baseball was 1933, just getting into four games for the Albany Senators. He married Mabel on May 15.

Whether Simmons had ever fully closed down the sign shop he’d set up back at age 15, we do not know. But he made a post-baseball career as a commercial artist as the owner of Simmons Signs and Simmons Store Fixtures and Neon, Inc. His work was wide ranging: interior design for organizations, clubs, and restaurants; designing bars, counter, showcases, and store fixtures; as well as making signs and painting murals.8

Pat Simmons suffered from hypertension and died at the age of 59, of a coronary thrombosis on July 3, 1968, in Albany, New York.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Simmons’ player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Letter from Mrs. Pat Simmons to Lee Allen of the National Baseball Hall of Fame dated August 24, 1968.

2 Hartford Courant, January 8, 1928.

3 Boston Globe, June 18, 1928.

4 Boston Globe, June 21, 1928.

5 Boston Globe, September 25, 1928.

6 Boston Herald, April 11, 1929 and March 2, 1930.

7 Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican, April 10, 1930.

8 Such was his description of the work in the player questionnaire he completed for the Hall of Fame. Mabel Simmons said that among the things he did was “paint beautiful attractions of Hollywood actors for the Theatre Lobbys; later on he designed Store Interiors and Store Fronts, also, Hotels, Motels, Restaurants and Bowling alleys, and then opened his Neon & Plastic Sign Shop. He was very creative, as everyone in this Tri-City area knows and boasts of Him. He was very kind, genial, honest, humble, model gentleman and very brilliant–a Genious, the people all commented when he died.” All spelling and capitalization is as it was in her letter to Lee Allen.

Full Name

Patrick Clement Simmons

Born

November 29, 1908 at Watervliet, NY (USA)

Died

July 3, 1968 at Albany, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.