Bob Groom

A tall, slender 6″2″, 175 pounds, Bob Groom possessed an athleticism, cunning, and tenacity that bespoke his roots in the southern Illinois coal fields, where his grandfather and father had found success as mine owner-operators. Born on September 12, 1884 in Belleville, Illinois, to John and Mary Catherine Dickinson Groom, he was named Robert for his paternal grandfather; he was the third-born of six and would be the oldest of three sons.

A tall, slender 6″2″, 175 pounds, Bob Groom possessed an athleticism, cunning, and tenacity that bespoke his roots in the southern Illinois coal fields, where his grandfather and father had found success as mine owner-operators. Born on September 12, 1884 in Belleville, Illinois, to John and Mary Catherine Dickinson Groom, he was named Robert for his paternal grandfather; he was the third-born of six and would be the oldest of three sons.

Called “Bobby” by his family, he went to public school in Belleville and as a teenage St. Louis-area semi-professional pitcher with at least one no-hitter to his credit, he caught the attention of Jake Bene, a well-known St. Louis baseball man. In early 1904, Bene bought the Fort Scott, Kansas Giants, in the Missouri Valley League, and he signed the 19-year-old Groom to his roster for a monthly salary of $60. The Giants were an early-season disaster; their losing 25 of their first 26 games inspired wholesale roster changes. Young Bobby Groom was not among the casualties, however, and he provided a highlight of the season in July, starting and winning both ends of a double-header. Newspapers described a tiny Fort Scott going “base-ball wild” after those games, even though its team eventually finished in last place with a record of 35-89 (.282); Groom’s record was a gloomy 8-26.

During the 1904 off-season, several of the Missouri Valley League teams, including the Springfield, Missouri, club, broke away to form a new eight-team league called the Western Association. While the Fort Scott team stayed in the Missouri Valley League, Bobby Groom played for the Springfield Highlanders in both 1905 and 1906, receiving a much-improved salary of $150 a month. In 1905, hindered by injuries, Springfield finished with a 54-80 record, but Bobby was 23-21. Springfield progressed in 1906 to 71-67 and Bobby improved to 20-18, earning him a promotion to Portland in the Pacific Coast League.

The 1907 Portland Beavers — just having been acquired by Judge Walter McCredie — was far from a good team, particularly early that season. Bobby pitched well but the Beavers’ fielding support had a way of letting him down. As Portland fell into last place, one sportswriter characterized the team’s play as “cheap horsehide vaudeville.” The team finished last in the league with a 72-114 (.388) record. In summing up the Beavers’ 1907 pitching, one West Coast writer described Bobby as having “the curves, speed and other attributes to win fame,” but he was afraid Groom was “too erratic and wild.” He finished with a 29-27-1 record, leading the league with 166 walks, 28 hit batsmen, and 22 wild pitches. On the plus side for 1907, Bobby gave the Beavers their first no-hit game in franchise history, a 1 hour-30 minute, 3-1 victory at home over the Los Angeles Loulous on June 16.

The 1908 Beavers fared much better, in large part because of Groom. Finishing second with a 95-90 record, Portland led the league as late as July 5, and Bobby was the Beavers’ star pitcher, recording a league-leading 29 wins versus 15 losses and 2 ties. After an early July flirtation with Cleveland and nationally-published rumors that Groom would soon join Addie Joss on the Naps’ pitching staff, it never came to pass. Instead, Washington bought him from Portland at the end of the season for $1,750. Walter McCredie, who would develop a reputation for sending important players to the majors, often called Groom “the best pitcher to go East” from the Pacific Coast League.

As a pitcher, Groom was fast and intimidating, and his demeanor generally serious and inscrutable. His ball movement was extraordinary, occasionally so extraordinary that inexperienced backstops had trouble catching him. In recalling Groom, American League umpire Billy Evans noted, “He was plenty fast and inclined to be wild,” but Evans described his curve as “magnificent and sweeping.” Building on a youthful fast ball, Groom developed a repertoire that included the curve Evans admired, a change of pace, and an occasional spitball moistened with tobacco juice. Evans believed that Groom never received full credit for his ability. “He happened to be on the same team as Walter Johnson, who overshadowed the whole staff,” said Evans. “If he had been with some other club, I dare say Groom would have been regarded as a speed marvel.” Evans also recalled Groom as a man with great confidence. “When he walked out to the rubber, you got the idea that he thought he was a pretty good pitcher. I agreed with him.”

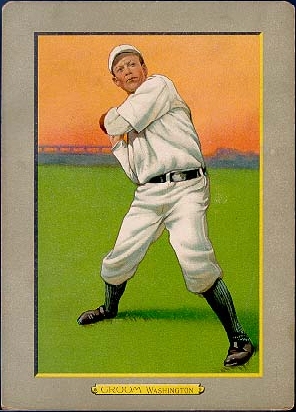

In his five years in the minor leagues, Bobby had won 99 games and lost 107. When he went to Washington, he was no longer “Bobby” but “Bob,” and occasionally dubbed “Sir Robert.” In 1909, the 24-year-old Groom joined 21-year-old Walter Johnson on the woeful (42-110) Washington Nationals. Bob did his share, losing 26 and winning only 7, but future Hall-of-Famer Johnson had a strikingly similar record, losing 25 and winning just 12. Debuting in relief against the Yankees on Tuesday, April 13, Bob pitched two innings, and the report was that he “displayed good control.” The April 14 game was rained out, and Bob started the game on April 15. He was described as “wild as the proverbial Texas pony.” After he walked or hit the first three batters and the fourth batter smacked a double, scoring two runs, Groom was unceremoniously removed. One local sportswriter quipped that Groom “could not find the plate with a search warrant.”

On April 28, Groom notched his first major league victory against Philadelphia in a ten-inning 3-2 complete game. But Washington fell quickly into last place with a 22-45 record, 23½ games out of first place, and Groom began what a now-disproved statistic claimed was a record-setting 19-consecutive-game losing streak. The true number, 15 games (corrected in 1991 by Frank J. Williams’ careful look at the records), was bad enough. Bob’s streak ran from early July to late September, with Washington scoring a grand total of 19 runs during Bob’s 15 defeats. Nonetheless, during this timeframe, Groom also pitched two tie games, including the record-setting 18-inning 0-0 tie against the Cobb-led Tigers when Bob relieved injured starter Dolly Gray. In 9⅔ innings of shutout ball, he continually frustrated both Ty Cobb and Wahoo Sam Crawford and was so impressive that even the Detroit fans cheered for him. Groom’s record of 7-26 tied the American league record for single season losses. While he led the team in walks and losses, his teammate Walter Johnson led the team in hit batsmen and wild pitches, losing 25 games himself in the process. The 1909 Nationals finished 56 games behind the league-leading Tigers, and at the end of the season they replaced one veteran manager, Joe Cantillon, with another veteran, Jimmy McAleer.

Washington (and Johnson and Groom) worked hard over the next two seasons, though the 1910 and 1911 records were only marginally better for Bob and the Nationals. The 1910 Nationals improved to a 66-85 record, good for a 7th place finish. Bob pitched 257 innings that year, winning 12 games and losing 17. The Nationals continued to hit poorly, finishing sixth in team runs scored per game. But at least one aspect of life was looking brighter for Bob: at the end of the season, he married his home-town sweetheart, Katherine Birkner, in a civil ceremony in St. Louis on November 19, 1910.

During the 1911 season Ty Cobb named Bob Groom — not even yet in his prime — to his list of the dozen pitchers he had the most trouble hitting. Indeed, Cobb’s lifetime batting average against Groom (.275 compared with Cobb’s overall lifetime average of .367) bore out Cobb’s assessment. Cobb’s difficulty may have had something to do with what Billy Evans had described as Groom’s typical demeanor. Nevertheless, the 1911 Nationals again finished in familiar territory, 7th place, with a 64-90 record. Bob won 13 and lost 17, pitching 254⅔ innings. Among his 1911 wins was a 6-2 victory over the Highlanders in New York on September 6, the day before his only child, a son named Robert, was born. Washington’s batting, never stellar, deteriorated further as the team dropped to seventh in team runs per game. The Nationals once again hired a new manager.

With Clark Griffith at the helm in 1912, the Nationals improved dramatically, winning 91, losing 61, and finishing in second place. Pitching a career-high 316 innings, Groom won 24 games and Johnson won 33, combining for over 60 percent of Washington’s victories. A major highlight of the 1912 season was the Nationals’ 17-consecutive-game winning streak. Bob started and won four of the games in that streak, his most impressive win being the last, on June 18. Only after that game was over did the Nationals’ fans learn the grit it had taken for Bob Groom to win that game. Before the game, he discovered a painful abscess on his back between his shoulders. The Nationals’ team physician recommended a debilitating operation, but Bob refused, and instead had the doctor insert a drainage tube. With the tube in his back, he put on his uniform and pitched a complete game, giving the Nationals a 5-4 victory over Philadelphia.

With Clark Griffith at the helm in 1912, the Nationals improved dramatically, winning 91, losing 61, and finishing in second place. Pitching a career-high 316 innings, Groom won 24 games and Johnson won 33, combining for over 60 percent of Washington’s victories. A major highlight of the 1912 season was the Nationals’ 17-consecutive-game winning streak. Bob started and won four of the games in that streak, his most impressive win being the last, on June 18. Only after that game was over did the Nationals’ fans learn the grit it had taken for Bob Groom to win that game. Before the game, he discovered a painful abscess on his back between his shoulders. The Nationals’ team physician recommended a debilitating operation, but Bob refused, and instead had the doctor insert a drainage tube. With the tube in his back, he put on his uniform and pitched a complete game, giving the Nationals a 5-4 victory over Philadelphia.

Though a perennial holdout at the start of each season, Bob returned to the Washington fold in 1913, and the Nationals once again finished second with a 90-64 record. Improved though the Nationals team was, their play was beset by an old bugaboo, inconsistent fielding. Bob finished with an even 16-16, pitching 264⅓ innings. One victory he did not get credit for was his July 18 eight-inning effort in 102 degree heat at St. Louis, where, between innings, the Nationals’ trainer wrapped Groom’s head in “ice-cold” towels. With the score tied at 1-1, Johnson came to his relief, and Washington rallied with four runs in the top of the 12th. Interestingly, when he’d been asked as a raw recruit in 1909 if he thought he could take the heat in Washington, he replied that he’d played in L.A. and he didn’t think the heat in the Capital would trouble him. Actually, St. Louis’ combination of heat and humidity — his native element — were generally the more challenging. Bob’s record indicates he thrived in the cooler weather of the early and late season.

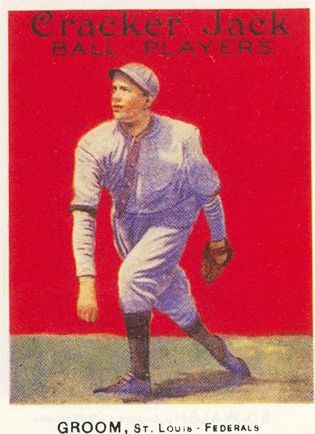

After five years with Washington, in 1914 Bob jumped at the chance to play homestands in St. Louis. Federal League (Handlan) Park was just a trolley ride from his home in Belleville. He signed on with the St. Louis Terriers, for whom he pitched 280 innings in 42 games, going 13-20 and tying a teammate for the dubious distinction of most losses in the league. The Terriers were hardly an offensive powerhouse, finishing last (62-89) by managing to score the fewest runs per game in the league. The following season, with their hitting bolstered by fresh players, the Terriers made a run for the 1915 pennant. They finished second, nosed out by Chicago by the closest pennant margin in baseball history, .001. Bob’s record that year was 11-11; he pitched 209 innings in 37 games.

When the Federal League collapsed in early 1916, Bob was one of the Terriers picked up by the St. Louis Browns. He acquired a new nickname as a Brownie, “Belleville Bob,” and he debuted for them with a handy 6-1 complete game victory in Cleveland in the Browns’ 1916 season opener. After a shaky early season, he finished strong, winning 10 of his last 11 games for a 13-9 record, having appeared in 41 games.

In 1917, the Browns’ team generally fell apart, finishing in that familiar 7th place, and Bob’s record that year was a disappointing 8-19. Dismal as the Browns were, Bob did provide them with their 1917 season highlight, pitching 11 innings of no-hit ball in a double bill on May 6, 1917. Brought in to relieve in the 8th in the first game of a double-header, Bob preserved the St. Louis lead and they won the game. Those two innings of no-hit ball were so shaky, however, that when Fielder Jones sent Groom out to start the second game, the St. Louis fans booed and fussed. With the season’s largest crowd in attendance, Belleville Bob answered the fans’ disapproval with a no-hit game. Toward the end, the cheering crowd roared with each pitch. After George Sisler picked up a hot grounder for the last out, the fans rushed onto the field, “captured” Bob, carried him around on their shoulders, and the next day, Browns’ owner Phil Ball rewarded him with a bonus of $100.

In the offseason before 1918, St. Louis put Bob on waivers, and Cleveland the team that almost got him ten years earlier, finally added Bob Groom’s name to its roster. But now he was 34 years old, and the aches and pains were beginning to take their toll. He finished his professional career that year, going just 2-2, pitching only 43 innings in 14 games. His major league career pitching record was 119-150 (.442), a record that almost exactly mirrors the combined records of his three primary teams (Nationals, Browns, Terriers) 638-738 (.463) Students of the game regard remembering him for his rookie season’s loss-total and wildness as a mistake, instead of admiring Bob Groom for his long-term tenacity, stamina, mental game, and phenomenal ball movement.

After leaving baseball, Bob returned to Belleville to head Groom Coal Company, a role for which he had prepared by working in the family business during summers. Because the coal business slowed during the summers, Bob was able to manage and play on Belleville’s crack White Rose team in the early 1920s. He had given up the medical studies he had pursued in St. Louis during the off-seasons of his early career, and because he regretted doing that, he made a special point of seeing that his son, also a hard-throwing right-hander, would graduate from college. Respected for his business sense, Bob sat on the board of St. Clair National Bank in Belleville from 1933 onward, and he and his wife Kate were active in Masonic and civic affairs. Through the 1930s, he remained active in baseball through the St. Louis Trolley League organization, which he served as an officer.

Then in May of 1938, a Belleville newspaper ran a story titled, “Bob Groom Is Making Baseball Comeback, but in Different Way.” As a headline, it was both tantalizing and prophetic. By mid-June, Bob Groom had chosen a junior tournament team for Belleville’s George E. Hilgard Post 58 of the American Legion. Gathering the diamond stars from Belleville’s two rival high schools, the soft-spoken “Mr. Groom” (as his players still call him) drilled and coached the Hilgards to the state and regional championship in their first year. Like little Fort Scott 34 years earlier, Belleville went baseball-wild. Bob Groom would continue to coach the Belleville Hilgards for a total of five summers, but at the start of the 1939 season, Bob’s beloved Kate — “team mom” to Bob’s boys — died suddenly when an appendicitis attack developed into peritonitis. It was a devastating blow to Bob and a huge shock for the team. Despite their loss, his 1939 Hilgards proved themselves to be another team with grit and went on to win the state game that season as well. They did not get to advance to regional play, however, for the coach of the defeated team (Berwyn, whom they’d defeated in 1938 as well) said he discovered a discrepancy in the birth date recorded of one player; he claimed a baptismal record did not agree with the city birth certificate. So the Hilgards’ 1939 season ended on a sad note, as it had begun.

After Kate’s death, Bob brought his son, daughter-in-law, and baby granddaughter to live in his suddenly too-spacious home. His granddaughter remembers him as a generous and gentle man who regularly dispatched her to the corner store for his chewing tobacco — a bag of shredded Mail Pouch and a plug of Horseshoe — with a treat of candy or ice cream for running the errand. Bob Groom died of pneumonia complicated by emphysema on February 19, 1948, at his home in Belleville and is buried in Walnut Hill Cemetery there.

For his role in founding and coaching Belleville’s first team for the George E. Hilgard Post, Bob Groom was inducted into the Hilgard Hall of Fame on February 23, 2008. A SABR Deadball memorial marker was dedicated at Belleville’s Whitey Herzog Field, home of the Hilgards, at the start of their 2008 season, the team’s 70th year.

This biography was based on John Stahl’s manuscript prepared for David Jones, ed., “Deadball Stars of the American League” (Potomac Books, 2006), and has been enlarged and edited by Catherine Groom Petroski.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Henry Petroski, Steve Steinberg, David Nemec, Rod Nelson, Dana Prusaki, Lee Ann James, Duke University Library, Patten Free Library (Bath ME), Belleville Public Library, Durham County Library, A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center, members of the SABR Deadball List, Mary Ellen Groom Prine, and the resources of the World Wide Web.

Sources

Newspapers

Contemporary accounts from the following publications: Aberdeen Daily News, Anaconda Standard, Atlanta Constitution, Baseball Magazine, Belleville Daily-Advocate, Belleville News-Democrat, Bessemer Herald, Bridgeport Telegram, Boston Daily Globe, Bucks County Courier-Times, Cedar Rapids Republican, Charlotte Observer, Chicago Tribune, Connellsville Daily Courier, Daily Kennebec Journal, Dallas Morning News, Decatur Daily Review, Dunkirk Evening Observer, Duluth News-Tribune, Fitchburg Daily Sentinel, Fond du Lac Daily Commonwealth, Fort Wayne Daily News, Fort Worth Star Telegram, Galveston Daily News, Grand Forks Daily Herald, Idaho Daily Statesman, Indianapolis Star, Janesville Daily Gazette, Kansas City Star, Kansas City Times, Lexington Herald, Lima Daily News, Lima Times Democrat, Lincoln Daily News, Lincoln Daily Star, Los Angeles Times, Lowell Sun, Macon Daily Telegraph, Madison Capital Times, Manitoba Morning Free Press, Mansfield News, Miami Herald, Modesto Evening News, New Castle News, New York Times, Oakland News, Oakland Tribune, Ogden Evening Standard, Ogden Standard Examiner, Racine Journal News, Reno Evening Gazette, San Antonio Express, San Jose Mercury Herald, Sandusky Star Journal, The Sporting News, Syracuse Herald, The State (SC), Trenton Evening Times, Warren Evening Mirror, Waterloo Evening Courier, Waterloo Times-Tribune, Wilkes Barre Times Leader.

Books

Bak, Richard. Peach: Ty Cobb, in His Time and Ours. Ann Arbor MI: Sports Media Group, 2005.

Broeg, Bob. The 100 Greatest Moments in St. Louis Sports. St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society Press, 2000.

Campf, Brian. “The Man Who Won Big for Portland,” Rain Check: Baseball in the Pacific Northwest. Cleveland: The Society for American Baseball Research, Inc., 2006, pp. 22-27.

Deveaux, Tom. The Washington Senators, 1901-1971. Jefferson NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2001.

Evans, Billy. “The Growl of the Wolves,” Liberty, IV, 9 (July 2, 1927), 53-54.

Fietsam, Robert C., Jr., et al. Belleville 1814-1914. Charleston SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2004.

Honig, Donald. Baseball America: The Heroes of the Game and the Times of Their Glory. New York: MacMillan Publishing Company, 1985.

Johnson, Walter. “Why I Signed with the Federal League,” Baseball Magazine, XIV, 6 (April, 1915), 52-62.

Lange, Fred W. History of Baseball in California and Pacific Coast Leagues 1847-1938: Memories and Musings of an Old Time Baseball Player. Oakland CA: Privately printed, 1938.

Nebelsick, Alvin Louis. A History of Belleville. Belleville IL: Privately published, 1951.

Nemec, David. The Official Rules of Baseball: An Anecdotal Look at the Rules of Baseball and How They Came to Be. Guilford CT: Lyons Press, 1999.

Okkonen, Marc. Baseball Memories 1900-1909: An Illustrated Chronicle of the Big Leagues’ First Decade. New York: Sterling Publishing Co., Inc., 1992.

Okkonen, Marc. The Federal League of 1914-1915: Baseball’s Third Major League. Garrett Park MD: Society for American Baseball Research, 1989.

Okrent, Daniel, and Harris Lewine. The Ultimate Baseball Book. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1979. [Historical text by David Nemec.]

Spalding, John E. Pacific Coast League Stars, Volume II: Ninety Who Made It to the Majors, 1905-1907. Place unknown: AG Press, 1997.

Steinberg, Steve. Baseball in St. Louis: 1900-1925. Charleston SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2004.

Thomas, Henry. Walter Johnson: Baseball’s Big Train. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995.

Williams, Frank J. “Bob Groom Did Not Lose 19 Straight Games in 1909!” Grandstand Baseball Annual 1991. VI (46-48).

Full Name

Robert Groom

Born

September 12, 1884 at Belleville, IL (USA)

Died

February 19, 1948 at Belleville, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.