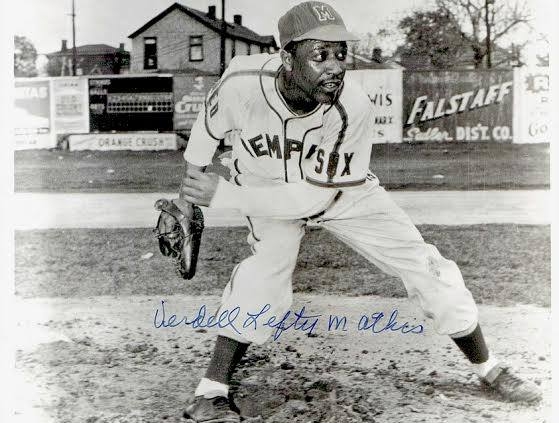

Verdell Mathis

Verdell “Lefty” Mathis, a pitcher for the Memphis Red Sox, was the premier southpaw in the Negro Leagues during the 1940s. His ability and popularity were such that he pitched in three East-West All Star Games, starting the 1944 and 1945 games for the West, and made the all-star roster a total of six times. As with many Negro League players, he also plied his trade south of the border in both Mexico and Venezuela. Of all his baseball exploits, the most exciting — according to Mathis himself — were the times that he pitched head-to-head against his boyhood idol, Satchel Paige, and came out on top.1

Verdell “Lefty” Mathis, a pitcher for the Memphis Red Sox, was the premier southpaw in the Negro Leagues during the 1940s. His ability and popularity were such that he pitched in three East-West All Star Games, starting the 1944 and 1945 games for the West, and made the all-star roster a total of six times. As with many Negro League players, he also plied his trade south of the border in both Mexico and Venezuela. Of all his baseball exploits, the most exciting — according to Mathis himself — were the times that he pitched head-to-head against his boyhood idol, Satchel Paige, and came out on top.1

While the jewel in Mathis’ pitching crown were his triumphs against Paige, he was also a good hitter who often played the outfield, and his overall baseball acumen was so great that he was listed on the preliminary ballot of the 2006 Special Committee on the Negro Leagues to be considered for induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Verdell Jackson Mathis, the fifth child born to Jackson and Sarah Mathis, entered the world on November 18, 1913, in Crawfordsville, Arkansas.2 The Mathis family eventually included 10 children, with an equal number of girls and boys. Jackson Mathis worked for the Missouri-Pacific Railroad, and he moved his family to Memphis, Tennessee, when Verdell was still a young boy.

In Memphis, baseball became important to Mathis at an early age. The Bluff City was home to the Red Sox, a member team of the Negro National League during Mathis’ youth. He remembered, “I went to all the games I could, and I would try to meet the players at the ballpark and at the hotel. I wanted to be around the baseball players all the time and be a part of anything that had to do with baseball.”3 During his time as a student at Memphis’ Booker T. Washington High School, Mathis played on the baseball team under coach William “Kid” Lowe, who also played left field and third base for the hometown Red Sox in parts of five seasons4.

A few years after high school, Mathis married Helen Dunn on June 3, 1936, and he worked as a laborer to support his wife and the children that came along soon thereafter. However, in 1937, Lowe — his old high school coach — formed a semipro baseball team and recruited Mathis to play on a barnstorming tour through several Midwestern states. Named the Brooklyn Royal Giants to evoke thoughts of their famous professional counterparts in New York, the team played numerous games against the Mineola (Texas) Black Spiders, who were managed by Reuben Jones. Mathis made a good impression on Jones, who later became instrumental in convincing Red Sox co-owner Dr. W.S. Martin to sign his discovery to a professional contract.5

On this same barnstorming tour, Mathis also got to cut his baseball teeth against white professional players, most notably Cleveland Indians pitcher Bob Feller. Mathis recalled, “He was just a kid then — maybe seventeen years old . . . He was already a star pitcher with Cleveland, but after the regular season, he was playing up there [in the Midwest]. Let me tell you, he was tough.”6 Mathis paid close attention to all his competitors as he honed his diamond skills. His true desire was to be an outfielder because he enjoyed hitting so much, but he conceded that “[t]he only way I could get to play in the Negro league was to pitch.”7 He also confessed, “At that time I wanted more than anything to play for the Memphis Red Sox.”8

Mathis continued to barnstorm with Lowe’s team through 1939 whenever the squad was on the road. Then, his opportunity to make his dream come true arrived when Reuben Jones was hired to manage the Red Sox, now a member team of the Negro American League, for the 1940 season. Jones wanted Mathis for his Memphis squad, but W.S. Martin offered a contract for only $65 per month. Mathis recalled feeling crestfallen because he would not be able to support his family which now included three children — two daughters and a son. He explained how Jones went to bat for him and told Martin:

“You sign Mathis to a contract for $125 per month . . . If he doesn’t make good, you pay him the $65 per month you offered him, and I will pay the $60 difference. On the other hand, if he does make good . . . you will pay the $125 per month, just like you would for any other top-quality player.”9

Martin agreed to Jones’ terms, and Mathis became a member of the 1940 Memphis Red Sox.

He made his first appearance as a professional ballplayer on April 14, 1940, in a game against the NNL’s Baltimore Elite Giants. Baltimore led, 3-1, in the fifth inning and had Red Sox starter William Sumrall in a bases-loaded-no-outs jam, so Mathis came to the mound in relief. He retired the first two batters he faced, but then George Scales followed with a grand slam far over the left field fence.10 More than 50 years later, Mathis lamented, “I still wish I had that pitch back!”11

Happily, Mathis’ fortunes soon changed, especially since he was also able to redeem himself by playing the outfield on days when he did not pitch. In the Red Sox NAL regular season home opener on May 12, a double-header against the St. Louis Stars, Mathis knocked a homer in the first game and was awarded a new hat for being the first Memphis batter to hit a round-tripper.12 Soon, the press noted that “Memphis appears to have a real find in Verdel Mathis, pitcher and outfielder.”13

The 26-year old Mathis continued to flash his versatility throughout the 1940 season. On August 11 he hit a three-run inside-the-park homer to support his own pitching as he went the distance in a 4-3 victory in the first game of a doubleheader against the well-known semipro Brooklyn Bushwicks at Dexter Park in Queens, New York. Mathis was performing so well that he had the chance to be a member of the West team for that year’s East-West All-Star Game, which was held at Chicago’s Comiskey Park. However, W.S. Martin did not allow him to join the West squad because he thought the young rookie “would come back with the ‘big head.’”14

While Mathis was disappointed at being blocked from the all-star team, his first season had been such a rousing success that he was now in demand elsewhere as well. Ships’ logs show that Mathis arrived in San Juan, Puerto Rico, on October 23, indicating that he likely played winter ball much earlier in his career than has previously been reported. It is unknown for which team Mathis played, and he did not stay long as he departed on his return trip to the U.S. on December 12, 1940.15

Although Mathis had always yearned to play for the Memphis Red Sox, he became one of the many players to opt for the higher salaries being paid by Mexican League teams. Mathis and Red Sox catcher Larry Brown began the 1941 season south of the border, where they played for the Alijadores de Tampico (Tampico Longshoremen). Mathis observed, “There were a lot of good players from the Negro Leagues playing down there at that time. Sometimes it seemed like we were playing an All-Star game back home.”16 During his brief stint with Tampico, Mathis pitched to a 4-5 record with a 3.98 ERA in 13 appearances that covered 74 2/3 innings.17

Mathis was back with Memphis, now managed by Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe, in time for a three-team double-header at Cincinnati’s Crosley Field on July 20 that opened the 1941 NAL regular season. After the St. Louis Stars defeated the Chicago American Giants, 11-7, in the first game, Mathis took the hill for Memphis against St. Louis and “[c]oasted to a 6 to 1 victory, allowing four hits in nine innings.”18 Having picked up right where he left off in 1940, Mathis again was selected by the West manager, Winfield S. Welch of the Birmingham Black Barons, for the annual East-West Game at Comiskey Park on July 27. Once again, Martin tried to prevent Mathis from joining the team, but the situation worked out differently this time. According to Mathis, “Martin had already told me that he wasn’t going to let me go, but Welch insisted that he couldn’t stop me from being in the game. I don’t know just what Welch said to Dr. Martin, but I wound up going to Chicago to be in the game.”19 Mathis was added to the West team as a pitcher, but he appeared only as a pinch-runner in the West’s 8-3 loss to the East.20

Negro League statistics are notoriously incomplete for many seasons, and the only official numbers for Mathis in 1941 show him to have posted a 2-1 record with a 0.81 ERA as a pitcher while he batted .450 in 20 at-bats for Memphis. Still, this small sample size at least hints at how well he had performed on the diamond that year.

Although Mathis already had performed to an all-star level in his first two seasons for the Red Sox, 1942 marked the year in which he became a widely-recognized star under his third different manager, catcher Larry Brown. Memphis opened the NAL season at home with a double-header against the Kansas City Monarchs on May 3. Mathis’ year got off to an inauspicious start when he was knocked out of the box in a 13-5 loss in the first game. The Red Sox also lost the second game to Satchel Paige, 4-3.21

Memphis again was the opponent for Kansas City as the Monarchs opened their home season on May 17. Mathis pitched an inconsequential relief stint in the first game of a double-header that K.C. won 7-0. In the nightcap, however, Mathis started and catapulted himself onto the national stage by winning a duel with the already-legendary Paige. Mathis allowed the Monarchs a mere two hits as he went the distance in an abbreviated seven-inning game and emerged with a 4-1 victory (second games of Negro League doubleheaders were normally shortened to seven innings).22

On the heels of this victory, the Chicago Defender ran a profile of Mathis that noted, “He is yet a good outfielder, a dangerous hitter and good base runner, but he is at his best when he is in the pitching box.”23 Furthermore, it asserted, “Verdel is the best left-hander in the Negro American league and is rapidly developing into the best pitcher in the game.”24

No matter Mathis’ pitching acumen, no hurler wins every game, and Mathis went down in defeat to the Monarchs in the second game of a July 4 doubleheader in Memphis that was played “[b]efore the largest crowd in the history of Martin’s Park for a regular league game.”25 Porter “Ankleball” Moss had pitched Memphis to a 7-6, 10-inning victory in the first game of the twinbill, but Mathis and Felix “Chin” Evans were touched up for six runs in the second inning of the nightcap as Kansas City coasted to a 9-3 victory.

Mathis did not have to wait long for a shot at redemption, as he again faced the Monarchs on July 7 at Pelican Stadium in New Orleans, a game in which he also faced off against Paige for the second time. The game was a classic pitchers’ duel in which Mathis gave up only four hits, escaped a bases-loaded jam in the sixth and Bonnie Serrell’s triple in the 10th, and emerged with a 1-0 triumph. Paige pitched the first five innings for Kansas City, striking out five and giving up three hits, before giving way to Connie Johnson who allowed Memphis only one additional hit but ended up as the hard-luck loser.26

Although Johnson was the losing pitcher on July 7, subsequent news articles tended to state only that Mathis had beaten the Monarchs and Paige in New Orleans (some accounts at least mentioned that Paige had not pitched the entire contest). In light of Mathis’ triumph in New Orleans and his May 17 victory over Paige in Kansas City, a Mathis-Paige rematch loomed in the near future. Monarchs co-owner J.L. Wilkinson, “arranged with Abe Saperstein a major spectacle: Satchel Paige Appreciation Day” and scheduled the Red Sox to be the Monarchs’ opponent in a July 26 doubleheader at Wrigley Field in Chicago.27 The nightcap, according to the Defender, would pit Paige in a “revenge game” against Mathis.28

Before the Chicago game could be played, however, Paige and Mathis dueled again on July 12 at Rebel Stadium in Dallas. Paige came out on top in an 11-0 Monarchs victory while Mathis did not finish the game.29 The Defender conveniently ignored the Dallas game in order to help Wilkinson and Saperstein hype the Wrigley Field match-up for all it was worth. In its July 25 edition, the paper ran quotes from both hurlers, who talked as though the upcoming game truly were a grudge match. Mathis boasted, “I beat him before and I’ll beat [him] again, and I’ll beat him Sunday.” Paige’s response urged Memphis to “Bring on Mathis . . . I’ve beaten better pitchers than he is and I’ll be ready for him Sunday.”30

When the big day rolled around, 20,000 fans were on hand at Wrigley Field. Porter Moss, who had defeated the Monarchs on Independence Day, triumphed again in the first game by a 10-4 score. Paige was feted between games and received a multitude of gifts before he took the mound to face Mathis in the seven-inning nightcap. As he most often did when he was in the spotlight, Paige prevailed on this occasion, 4-2, and “would probably have had a shutout had there not been an error behind him in the seventh. The Red Sox scored their only two runs at this time.”31

This loss to Paige was the beginning of a brief rough patch in Mathis’ breakout season. On August 2 he lost a tough 2-1 decision in the second game of a doubleheader against the Cincinnati Ethiopian Clowns at Crosley Field. Mathis dueled with Clowns starter Leo “Preacher” Henry for seven innings before the latter ceded the mound to Dan Bankhead, who pitched four frames to earn the win as Mathis surrendered two singles and a sacrifice fly in the bottom of the eleventh that resulted in the Clowns’ triumph.32

Three days later, Mathis took the hill against the semipro St. Joseph Autos at that team’s Edgewater Park. Although the Red Sox trounced the Autos, 9-2, and Mathis struck out 10 batters, the local press noted that he also “was exceedingly generous with walks, issuing nine. Had the Autos taken advantage of this, they would have tallied more than two markers.”33 In spite of Mathis’ wildness, he had notched another victory as he headed toward his first East-West All-Star game mound appearance.

Mathis did not participate in the annual East-West showcase game at Comiskey Park on August 16, which was won by the East team, 5-2. However, he was on the West team roster for the second game at Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium on August 18. When the East team jumped on West starter Eugene Bremer for five runs in the top of the third inning, Mathis entered the game in relief. He allowed single runs in both the fifth and sixth innings but both were unearned, and he acquitted himself well over his 3 1/3 innings stint as he yielded four hits, struck out two batters, and issued no walks in the West’s 9-2 loss.34

Memphis finished in fourth place in the Negro American League in 1942, but Mathis emerged as an ace over the course of the season. On August 25, he pitched Memphis to a 9-3 victory over the Cincinnati-Cleveland Buckeyes, an NAL rival, at Pelican Stadium. It was Mathis’ 21st win against only six losses versus all opponents — league and exhibition — during the season.35 Red Sox skipper Brown put the last jewel in Mathis’ crown when he picked his leading moundsman for a Negro American League all-star team that played a three-game exhibition series at Pelican Stadium in late September.

In April 1943, Mathis once again succumbed to the lure of a higher paycheck, but also to the prospect of playing for a more competitive team. Throughout the history of the Negro Leagues, it was not uncommon for teams to raid the rosters of their competitors, especially squads in the rival league. Such an incursion was at the heart of Mathis’ defection to the Philadelphia Stars, which was precipitated by Philadelphia’s loss of several starting players to military service. According to historian Neil Lanctot:

“While [Stars owner] Ed Bolden admitted it would be ‘almost humanly impossible’ to find equivalent replacements, manager Goose Curry, a Memphis resident during the winter months, recognized the financially shaky local NAL franchise as a potential gold mine. With the probable tacit blessing of the Stars’ ownership, Curry met with several Memphis players, eventually signing pitchers Steve Keyes, Willie Burns, and Verdell Mathis after reportedly offering a $25 per month raise, train fare to Philadelphia, and $100 upon arrival.”36

Dr. B. B. Martin, Red Sox co-owner along with his brother Dr. W. S. Martin, lamented the fact that his team had been “practically wrecked” and was glad that rain had canceled his squad’s April 18 doubleheader against the Chicago American Giants, “thus saving the Red Sox from being humiliated on the playing field.”37 Another brother, Dr. J. B. Martin, who owned the Chicago team and was the NAL’s president, planned to protest the Stars’ raid to NNL president Tom Wilson.

Curry denied any wrongdoing on his part and claimed that “Mathis was now employed by Sun Shipyard, and the Stars hoped to use him during his stay in the Philadelphia area.”38 In spite of Curry’s disingenuousness, the presidents of the two leagues — Wilson and Martin — along with other league representatives met in Philadelphia on June 1 to settle the matter. An agreement was reached in which all players would be returned to their former teams, “and the now harmonious league presidents issued a subsequent statement warning that ‘we are not going to allow any one team to be bigger than the two leagues . . . All teams must respect rules and regulations.’”39 June 15 was set as the deadline for all players to return to their respective clubs — a total of five teams had been involved in the dispute — and failure to heed the order would “mean suspension for the players and clubs, it was declared.”40

Mathis pitched to a 2-2 record for the Stars during his brief stint in the City of Brotherly Love before rejoining his former team on June 11.41 Memphis manager Larry Brown sent Mathis to the mound against the American Giants the next day, and he responded with a sterling performance in a 3-1 victory in the opening game of a doubleheader.42

Mathis resumed his role as the Red Sox ace and apparently was back in Memphis management’s good graces as well. Prior to an exhibition game against the Fremont Green Sox at Toledo’s Swayne Field on June 17, the press noted, “That Memphis is taking no chances with the game is indicated by the fact that Verdel Mathis, one of the nation’s top sepian [sic] hurlers, will be on the mound for them. Owner B. B. Martin made that decision when informed that the [Green] Sox had knocked off the Clowns last year.”43

Mathis may have been hoping for another rematch against Satchel Paige when it was announced that Wrigley Field would again host Satchel Paige Day on July 18. As it turned out, however, the Kansas City Monarchs already had a game scheduled for that date, so they loaned Paige to Memphis and he pitched for the Red Sox against the New York Cubans.44 Paige pitched five no-hit innings against the New Yorkers, Neil Robinson hit a homer for the game’s only run, and Porter Moss finished Memphis’ 1-0 shutout on Paige’s big day.45

Perhaps inspired by their participation in the Satchel Paige Day games in two consecutive years, the Red Sox decided it was time to host Verdell Mathis Day. Sunday, August 8, was the day set aside to honor Mathis. The game was played against Cleveland at Russwood Park, home of the minor-league Memphis Chicks. Mathis was presented with a $50 war bond, and three other bonds were handed out to fans, “but the Cleveland Buckeyes weren’t so very obliging, whipping the Memphis Red Sox, 2-1 and 4-0, in two well played games.”46 Perhaps so that Mathis could bask in all of the adulation, he did not pitch in either game.

When the West beat the East, 2-1, in that season’s All-Star game at Comiskey Park on August 1, Mathis was not on the West squad for the first time since 1940. However, on September 2, he took part in a landmark game of a different kind at the same venue. That date marked the first night game between Negro League clubs at Comiskey as the American Giants hosted the Red Sox.47 Shortstop Red Longley hit a two-RBI single in the sixth inning as Mathis held Chicago to five hits in a 2-0 Memphis victory.48

By the end of the regular season, Mathis had pitched to a 4-2 record for fifth-place Memphis to go along with the 2-2 record he had posted for Philadelphia in NNL games.

In early October, with Memphis’ season over, Mathis earned some additional money when he joined the revamped Atlanta Black Crackers and earned two mound victories in games played at Atlanta’s Ponce de Leon Park. The first game took place on October 6 as the Black Crackers hosted the NNL-champion Homestead Grays. The Grays were deadlocked at three victories apiece in their World Series tilt against the NAL-champion Birmingham Black Barons, but they took the opportunity that an off-day provided to participate in this exhibition game.49 Mathis did his best to make the partisan Atlanta crowd happy as he pitched three-hit ball and struck out seven Grays batters as the Black Crackers prevailed, 7-3, against the powerful lineup of the soon-to-be Negro League Champions (Homestead defeated Birmingham 4-3-1 in the World Series).50

Mathis took the mound for Atlanta once more in the first game of a doubleheader against the New York Cubans on October 10 and again pitched the Black Crackers to victory in an exciting 3-2 game. He held the Cubans to five “well-scattered” hits while striking out four batters, and he survived a run-scoring threat in the ninth when Larry Brown tagged a runner out at the plate to end the game.51 It was a fitting way for Mathis’ 1943 season to conclude.

In 1944, with Reuben Jones back at the helm, Memphis slogged to another fifth-place finish in the NAL. Mathis, however, continued to add to his list of career highlights. The game that he savored most in his entire tenure as a professional pitcher took place at Wrigley Field on July 30. The Monarchs and Red Sox played a doubleheader that Sunday and, for the third consecutive year, Satchel Paige was honored with gifts between games. Memphis centerfielder Neil Robinson was also scheduled to be honored.52 The second game would be a rematch of 1942’s Paige-Mathis duel.

Memphis took the opening game by a 6-4 score, and then Mathis showed his mettle to Paige and the 10,000 fans in attendance as “the little left hander virtually won his own game . . . 3 to 2” in the abbreviated nightcap.53 Kansas City’s Robinson hit a homer in the fourth inning on his day, and Memphis tied the game at two runs apiece in the seventh to force an extra inning. In the top of the eighth, Mathis reminded everyone that he was also still a capable hitter as he tripled and scored on Fred McDaniels’ single to provide the winning margin. It was the last head-to-head matchup ever between Mathis and Paige, and Mathis finished his career with a 2-2 record against his boyhood hero.

Mathis continued to hit and pitch Memphis to victory on August 6 at Birmingham’s Rickwood Field. In the first game of a doubleheader against the Black Barons, he had “two hits in three official times at the platter, scored a run, and was purposely walked in the ninth” and allowed Birmingham only six hits as the Red Sox won, 4-3.54 He once again earned a spot on the West all-star team for the annual tilt at Comiskey Park on August 13.

Mathis became the West’s starting pitcher when Paige decided to forgo the event.55 Mathis pitched three innings and allowed only three hits and one earned run..The West eventually triumphed, 7-4, but Gentry Jessup, who pitched the fourth through sixth innings, emerged as the winning pitcher.56

One week later, again at Comiskey Park, Mathis struck out nine in outdueling Jessup, 3-2, in the opening game of a doubleheader against the Chicago American Giants. Memphis’ victory ended Chicago’s hope of winning the Negro American league second half.57 Although his team could do little more than play the role of spoilers, Mathis’ star continued to shine.

In 1945, Brown piloted the woeful Red Sox to a last place finish in the NAL, and Mathis’ “workload took its toll” on his arm.58 In mid-July, prior to a Monarchs-Red Sox doubleheader at Detroit’s Briggs Stadium, the press noted that, “During the early weeks of the current season, Mathis did not hit his form, but in recent weeks he has been going like a prairie fire sweeping across the plains of Kansas.”59 Mathis swept his way into Comiskey Park on July 30 to make his second consecutive start for the West team in the annual all-star game. This time, Mathis threw three no-hit innings in which he struck out four batters. The West had an 8-0 lead when he ceded the mound to Jessup. In a reversal of his fortunes from the previous year, Mathis was the winning pitcher as the West triumphed, 9-6.60

In late September, Mathis was a member of the Kansas City Royals team that played a short series against Butch Moran’s All-Stars in California Winter League play.61 After this series, Mathis departed for Pelican Stadium in New Orleans, where he was the South’s starting pitcher in the North-South all-star game. A preview article about the game mentioned that Mathis had posted a 17-5 record for Memphis during the season, which was an impressive ledger for a pitcher who had toiled for a last-place team.62 After the season, Mathis had surgery to remove bone chips from his left elbow, but arm troubles would plague him for the remainder of his career.63

The 1946 season started well enough for Mathis. He defeated the Indianapolis Clowns, 5-4, in the first game of an Easter Sunday doubleheader in Memphis on April 21.64 In the Monarchs’ home opener in May, he allowed only six hits but lost, 3-0, to Kansas City’s future Hall of Famer Hilton Smith.65 However, by the time the Red Sox opened the second half of the NAL season against the Cleveland Buckeyes on July 7, the Chicago Defender reported “the collapse of their star hurler Verdel Mathis, who has been bothered with a sore arm most of the season, but is now recovering.”66 As it turned out, Mathis struggled through the remainder of the season. After the regular season, he again participated in the North-South all-star game, and he joined the K. C. Royals for another series in California. In one game out West, Mathis combined with Booker McDaniels and Jimmy Newberry on a two-hit shutout in which Mathis earned the win against Manny Perez.67

The 1947 season became a repeat of the previous season for both Mathis and the Red Sox, as Memphis finished in fourth place and many news articles focused on the condition of Mathis’ arm. Memphis’ 6-3 victory over Birmingham on June 15 was labeled as his “best game of the season” and, on June 28 the Defender reported that “Mathis is back in his old form after being sidelined with a sore arm. He has his power ball again and has been effective in recent games.”68 Mathis managed to pitch well enough to be named to the West roster for the July 27 East-West classic at Comiskey Park, but he did not participate in the game (perhaps due to his arm troubles).69 After the season, he played winter ball in Venezuela, where other Negro League luminaries – including Roy Campanella, Don Newcombe, Johnny Wright, and Luke Easter – were also plying their trade.70

After Mathis returned stateside for the 1948 NAL season, he must have felt stuck in a time loop, as he continued to struggle and the Red Sox finished in sixth place. On May 2, at Martin Park in Memphis, Kansas City knocked Mathis out of the Red Sox home opener with six runs in the sixth inning as the Monarchs triumphed, 9-4.71 One event of note, however, occurred on June 6 at Cleveland’s League Park when television station WEWS broadcast a doubleheader between Memphis and the Cleveland Buckeyes; the game was also broadcast over the radio by station WSRS. Mathis hurled Memphis to a 4-2 victory in the opening game, which was the first Negro League game ever to be simulcast on TV and radio.72

Perhaps tired of Memphis’ losing ways, Mathis opted for a change of scenery in mid-season. On July 31, the day after the Red Sox lost, 10-5, to the St. Joseph Auscos of the Michigan-Indiana League, the St. Joseph Herald-Press reported that the Auscos had signed Mathis and a teammate, right-hander Bob Sharpe, away from Memphis.73

Mathis’ defection to St. Joseph may have caused him to miss out on the opportunity to pitch in the 16th annual East-West game at Comiskey Park on August 22. He had once again been named to the roster but did not see any game action in what turned out to be his final East-West classic.74Although Mathis had signed with the Auscos at the end of July, he did not join the St. Joseph squad until August 23. While Mathis had been in Chicago for the East-West game, the Herald-Press explained away his “delay in arriving [as] due to the press of private matters.”75

Unfortunately for both Mathis and the Auscos, his stint with the team did not go as planned. In his first start for St. Joseph on August 25, Mathis was hammered by the South Bend Studebakers for seven runs in 4 2/3 innings as the Auscos lost, 11-2. Four days later, he was inserted into a game against the Homestead Grays in the ninth inning, and he surrendered a walk and a double that resulted in the two runs that gave the Grays an 8-7 victory. He finally garnered a win in a 9-5 triumph over Kenosha on August 31 but still surrendered four runs in 3 2/3 innings. Mathis’ lone victory for the Auscos was his swan song for the team as “[m]anager Benny McCoy announced after the game that Mathis must report back to the Memphis Red Sox by tomorrow or face a two-year suspension in the Negro American league. Mathis plans to return to his home sometime today.”76 It marked the second time in his career that Mathis had jumped his contract with his hometown team only to have to return to the Red Sox in order to avoid being suspended. Thus, Mathis finished another lackluster season with Memphis. Afterward, he played on an all-star team managed by Larry Brown that competed against Jackie Robinson’s All-Stars in October.77

The integration of organized baseball brought about a rapid decline in the quality of Negro League teams and in their financial viability. Gone were the days when the Red Sox held spring training in Hot Springs, Arkansas; now the team prepared for the 1949 season by practicing on its home field, Martin Park.78 News coverage of the Negro Leagues was sparse by 1949, as even the African American press focused on black ballplayers in Organized Baseball. Mathis did the best he could on the mound as he languished on another last-place Red Sox squad. His season highlights involved competition against soon-to-be major-league stars. In late July, Mathis pitched a five-hit, 6-1 victory against the Birmingham Black Barons and future Hall of Famer Willie Mays in the second game of a doubleheader in Memphis.79 On August 21, he came up on the short end of a duel with Baltimore Elite Giants hurler Joe Black, who would become the 1952 National League Rookie of the Year with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Black prevailed by a 7-1 score against Mathis and the Red Sox in the first game of a doubleheader on this occasion.80

In October, well after Memphis’ season had come to an end, Mathis alternately played for and against the Satchel Paige’s All-Stars team, but he was listed as a right fielder rather than a pitcher.81

In 1950, with his pitching arm in disrepair, Mathis led a peripatetic baseball existence. He spent the early part of the year as a member of the Southern Minnesota League’s Rochester Royals. On May 12 the Winona Republican-Herald announced that Mathis “has been named by manager Ben Sternberg to make his debut for the Royals. It will be primarily a try-out for the dusky skinned chucker and [Gready] McKinnis will be kept handy in case Mathis fails.”82 Mathis made the cut and, on May 23, he again was the Royals’ starting pitcher in a game against the Winona Chiefs. Mathis hit a home run in support of his own cause, but he eventually gave way to McKinnis, who earned the win in a 9-8, 10-inning thriller.83

On July 1 it was reported that Rochester right-hander Gene Smith had returned from an injury, which led to Mathis’ release.84 A short time later, he was picked up by a team in Le Sueur, Minnesota, where his hitting, rather than his pitching, garnered notice. On August 8, the Republican-Herald noted that “Verdell Mathis, former Rochester pitcher, is hitting over .409 for Le Sueur.”85 Mathis’ outstanding batting average notwithstanding, his brief tenure in Minnesota was nondescript.

In October Mathis moved south to the warmer climes of Texas, where he played for two different teams. An October 6, news article noted that the “probable starting hurler for the [Houston] Eagles will be Verdell Mathis or Jehosie Herd [sic], both left-handers” for the team’s game against the Mexican League’s Monterrey Sultanes in Galveston, Texas.86 Two weeks later, Mathis was listed as a member of the Negro American League All-Stars for an exhibition game against Luke Easter’s All-Stars, which consisted of major- and minor-league players, for an exhibition game that also took place in Galveston.87 At this point, Mathis’ professional baseball career was effectively over, save for occasional appearances as a member of the barnstorming Roy Campanella’s All-Stars in 1951 and 1952.88

Upon his retirement from baseball, Mathis moved his family, which now included three daughters (Helen, Jean, and Ann) and his son (Verdell Jr.), to New York City, where he worked for Chock Full O’ Nuts, the company that eventually made the retired Jackie Robinson the first African-American executive in a white-owned business. Mathis later recalled, “The good thing about living in New York was that I got to see a lot of baseball games. I went to see the New York and Brooklyn teams play the whole time I was there.”89 However, in 1969, Mathis moved back to Memphis “because it was home.”90 He worked for the Colonial Country Club in Memphis for 15 years and then retired.91

Mathis was one of the many Negro League players for whom the integration of organized baseball came along too late, as his injured arm denied him any opportunity to make it to the majors. In 1989, when several members of the Red Sox and Black Barons were honored in Atlanta, Mathis reflected upon the situation: “When I think about it, I get a little downhearted, to myself . . . People that know me walk up to me and say, ‘You know what? If they just had blacks in the league, you would have made it.’ That makes me feel bad . . . I just smile it off. But I think about it to myself, I think about it to myself. A whole lot.”92

Although the wounds inflicted by Jim Crow segregation still cut deep, Mathis acknowledged that he had enjoyed his career as a ballplayer. In a 1992 interview, he explained, “My career was great. I mean, it was great for me. Not everybody gets to do what they want. When I was a teenager, I made a wish to someday play for the Memphis Red Sox. I got exactly what I wished for. That doesn’t happen very often.”93

In 1997, Mathis received another belated honor when he was included on the Milwaukee Brewers’ Negro League Wall of Fame at County Stadium, which was unveiled at a pregame ceremony on July 18. Unfortunately, Mathis’ health prevented him from being able to attend the event, so Sherwood Brewer, a former infielder, stood in for him.94

Verdell Mathis died of pneumonia on October 30, 1998, in Memphis. He was buried in Memphis Memory Gardens next to his wife of 57 years, Helen; the couple was survived by their four children.

Mathis was considered for induction to the Hall of Fame by the Special Committee on the Negro Leagues but was not among the players who were chosen. Although Mathis was not enshrined in Cooperstown, New York, he became one of 22 athletes to be inducted as the inaugural class of the Memphis Sports Experience and Hall of Fame on October 10, 2019.95 In the eyes of players who had competed against him, Mathis had long been worthy of such honor. As pitcher Nap Gulley declared in a 1999 interview, “[Mathis] was the best pitcher of our time. He should have been in the Hall of Fame . . . Verdell could win. Just give him one run and he wouldn’t have a problem. He beat Satchel more than Satchel beat him.”96 Indeed, Mathis had done just that when he was one of the shining stars of the Negro Leagues.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Paul Doutrich and Joe DeSantis and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Sources

All Negro League statistics and team records were taken from Seamheads.com except where otherwise indicated.

Ancestry.com was consulted for census information, marriage and death information, and other public records.

Notes

1 Prentice Mills, Black Ball News Revisited: Interviews and Essays Drawn from the Journal of Negro League Baseball History (Nashville: Red Opel Books, 2019), 80.

2 Mathis’ birth year is usually listed as 1914. However, his obituary states that he was 84 years old at the time of his death on October 30, 1998. Obituary writers normally do not round up a person’s age, and Mathis’ next birthday was still 19 days in the future; therefore, if Mathis was already 84, then he must have been born in 1913. The 1920 and 1930 census both list Mathis’ birth year as “abt 1914”; however, Mathis’ birth date was a late one, and he was already listed as six years old at the time of the 1920 census and 16 at the time of the 1930 census; again, if he was already that age at the time the census was taken, then his birth year was 1913 rather than 1914.

Additionally, it should be noted that census takers were notorious for butchering names and Mathis did not escape their misspellings. In the 1920 census he was listed as “Verdella Mathesius”; in 1930, he was named as “Verdell Matthews,” by which name he was also listed in the state of Arkansas’ marriage records; and the 1940 census listed him as “Verdel Mathis.” This last spelling, which includes only one “l” in his first name, can also be found in many of the news articles about Mathis during his playing career. However, in later years and in his obituary, his name was always spelled “Verdell”; thus, this spelling of Mathis’ name will be used throughout this article for the sake of accuracy and consistency, except for instances in which a source is being quoted directly.

3 Mills, 72.

4 Lowe’s Negro League career spanned a total of eight seasons and included stints with the Indianapolis ABCs (1921), Detroit Stars (1922, 1924), Memphis Red Sox (1925, 1927-30), and Nashville Elite Giants (1930).

5 Mills, 72-73.

6 Mills, 74.

7 Brent Kelley, Voices from the Negro Leagues: Conversations with 52 Baseball Standouts (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1998), 123-124.

8 Mills, 74.

9 Mills, 76.

10 “Red Sox Lose to Elites,” Chicago Defender, April 20, 1940: 22.

11 Mills, 77. When Mathis recalled all of these events after more than half a century, he gave a different account of the game. Mathis stated that he had taken the mound in the ninth inning with the game on the line and had struck out the first two batters before surrendering Scales’ home run. Whether this was embellishment or simply a fuzzy memory after so many years, original news articles provide the accurate account of what happened.

12 James H. Purdy, Jr., “Memphis Red Sox Open with Double Victory,” New York Amsterdam News, May 18, 1940: 21. Purdy wrote that “Fred Mathis, Red Sox centerfielder,” hit the homer, thus conflating Mathis and teammate Fred Bankhead into one player. However, Mathis played center field and Bankhead played second base, so it was clearly Mathis who hit the home run.

13 Sam Brown, “Memphis Red Sox Play Monarchs Two Sunday,” Atlanta Daily World, May 24, 1940: 5.

14 Mills, 77.

15 Although there is no statistical record for Mathis from this time period and no major sources list him on the roster of any team, it appears likely that he participated in Puerto Rican winter league play ever so briefly.

16 Mills, 80.

17 Pedro Treto Cisneros, The Mexican League: Comprehensive Player Statistics, 1937-2001 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2002), 475.

18 “St. Louis Stars Defeat Chicago Then Lose to Memphis Red Sox, 6-1,” Chicago Defender, July 26, 1941: 22.

19 Mills, 78.

20 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1953 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 169.

21 “K.C. Monarchs Wallop Memphis, 13-5 and 4-3,” Chicago Defender, May 9, 1942: 19.

22 “Kansas City Splits Even with Memphis,” Chicago Defender, May 23, 1942: 20.

23 Sam Brown, “Memphis Star Left-Hand Hurler,” Chicago Defender, June 6, 1942: 20.

24 Brown, “Memphis Star Left-Hand Hurler.”

25 Sam Brown, “Kansas City and Red Sox Divide Pair,” Chicago Defender, July 11, 1942: 19.

26 “Memphis Red Sox Defeat Monarchs in Tenth Inning,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, July 8, 1942: 14. Later news articles often stated that this July 7 game was an 11-inning (or, in one case, 13-inning) affair; for instance, the July 18 edition of the Chicago Defender stated that it was an 11-inning game and that Paige had pitched six innings (rather than five). Since the Times-Picayune was the paper of the city in which the game was played and its report appeared the day after the game was played (and included a line score of 10 innings), it may be presumed to be the accurate account. (For the Defender’s account, see: “Paige Faces Mathis in Revenge Game at Cub’s Park, Sunday, July 26,” Chicago Defender, July 18, 1942: 20).

27 Mark Ribowsky, Don’t Look Back: Satchel Paige in the Shadows of Baseball (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994), 209.

28 “Paige Faces Mathis in Revenge Game at Cub’s Park, Sunday, July 26,” Chicago Defender, July 18, 1942: 20.

29 “Opponents Blanked by Negro Pitcher,” Dallas Morning News, July 13, 1942: 7. Although this game rarely received mention, Mathis recalled it decades later, saying, “I remember in Dallas one Sunday it was awful hot. Satchel beat me down there.” (See John B. Holway, Black Diamonds: Life in the Negro Leagues from the Men Who Lived It (New York: Stadium Books, 1991), 148.)

30 “Chicago to Honor Satchel Paige Sunday/Paige Will Face Lefty Mathis and Memphis at Wrigley Field July 26,” Chicago Defender, July 25, 1942: 19.

31 “Satchel Paige Thrills Crowd in Chicago Tilt,” Atlanta Daily World, August 1, 1942: 5. The Chicago Defender reported the attendance as 18,000; however, all other newspapers, including the Chicago Tribune, reported the crowd size to be 20,000. See the following: “Chicago Fans Honor Satchel Paige Who Wins 4-2,” Chicago Defender, August 1, 1942: 19 and “Kansas City and Memphis Divide Paige Day Games,” Chicago Tribune, July 27, 1942: 17.

32 “Memphis Beats Clowns then Loses in Eleventh,” Chicago Defender, August 8, 1942: 20. Dan Bankhead became the first black pitcher in the major leagues when he debuted with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947.

33 “Tucker’s Men Tamed by Lefty Mathis,” St. Joseph (Michigan) Herald-Press, August 6, 1942: 11.

34 Lester, 204.

35 “Buckeyes and Red Sox Meet Here Tonight,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, August 25, 1942: 11; “Memphis Red Sox Beat Cincinnati ‘9’ in Negro Contest,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, August 26, 1942: 12. Seamheads.com, which only provides statistics for official league games, shows Mathis’ record in NAL play to have been 3-5 in 1942. However, Mathis’ 21-6 ledger after the August 25 game gives a better indication of his pitching acumen and the reasons why he was so highly regarded.

36 Neil Lanctot, Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), 136.

37 “Philadelphia Raids Memphis Red Sox/Mathis, Bell, Longley and Bradford Go,” Chicago Defender, April 24, 1943: 21.

38 Lanctot, 137.

39 Lanctot, 137.

40 “Tom Wilson Acts with J. B. Martin to End Disputes,” New York Amsterdam News, June 12, 1943: 15.

41 “Mathis in Final Game for Philly Stars,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 10, 1943: 16.

42 “Returns to Red Sox — and Wins,” Chicago Defender, June 12, 1943: 19.

43 “Sox to Play under Lights/Meet Memphis Red Sox at Swayne Field, Toledo, on Thursday,” Fremont (Ohio) News-Messenger, June 15, 1943: 7.

44 It was not unusual for Negro League teams to add new games to their schedules as opportunities presented themselves. The reason for Satchel Paige Day being scheduled for a date on which his team (the Monarchs) was unavailable is unknown, but it also was not unheard of for teams to lend players to another team, as the Monarchs did in this situation. Sometimes a player might be loaned out due to his drawing power, which was certainly the case with Paige in this instance, while at other times players might be put on loan simply for an opponent to be able to field a team and play a game. In the latter instance this was done in order for a team to field enough players so that a game would not be canceled, as a cancellation would cause both teams to miss out on their much-needed shares of the gate receipts.

45 “Satchel Paige Stars: Memphis Nine Wins, 1 to 0,” Chicago Tribune, July 19, 1943:21; “Satchel Paige Blanks N. Y. Cubans in Chicago,” Atlanta Daily World, July 23, 1943: 5; “25,000 See Paige Trim Cubans, 1-0,” Chicago Defender, July 24, 1943: 11. It must be noted that, five decades later, Mathis claimed in numerous published interviews that he won a 2-1 victory over Paige on Satchel Paige Day in 1943. See Mills, 79-80; Kelley, 126-127; and Holway, Black Diamonds, 148. In the Kelley interview, Mathis even averred that a researcher had told him that he was in possession of a 1943 Chicago Defender article that substantiated his claim. As the three news articles cited here (including one from the Defender) indicate, Paige pitched for Memphis on Satchel Paige Day in 1943 and Mathis did not pitch at all; additionally, the news reports cited in note #29 (above) indicate that Paige triumphed over Mathis on Satchel Paige Day in 1942. Mathis did eventually defeat Paige at Wrigley Field in 1944 on what was dubbed “Neal Robinson Day” (though Paige was also presented with gifts for the third consecutive year); the latter game will be discussed and documented later in this article. Mathis’ assertion does not appear to be an instance of self-aggrandizement as he did own a 2-2 career record in head-to-head match-ups with Paige (and also won the 10-inning decision over the Paige/Johnson tandem in 1942); rather, it appears simply to be an example of the effects that time can have on a person’s memory, especially in regard to specific details of long ago events.

46 “Buckeyes Take Two,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 14, 1943: 19.

47 “Chicago Giants Face Memphis Nine Tonight,” Chicago Tribune, September 2, 1943: 25.

48 “Memphis Red Sox Beat American Giants, 2 to 0,” Chicago Tribune, September 3, 1943: 22.

49 “Fans Await Grays-Black Crax Thriller; Clark Panthers Ready for Ft. Benning,” Atlanta Daily World, October 6, 1943: 5. This exhibition game was held to raise money for the Community and War Fund.

50 “Atlanta Black Crackers Upset Homestead Grays by 7-3 Margin,” Atlanta Daily World, October 7, 1943: 2.

51 “Black Crax Turn Back New York Cubans/Mathis Tops Barnhill in ‘Hot’ Hurling Duel,” Atlanta Daily World, October 11, 1943: 5.

52 “Negro Ace to Face Memphis Red Sox Today,” Chicago Tribune, July 30, 1944: 21. It should be noted that Neil Robinson’s first name was often misspelled as “Neal” by the press, as was the case in this article.

53 “Memphis Takes Twin Bill from Kansas City, Paige,” Chicago Defender, August 5, 1944: 7.

54 “Black Barons Divide Double Bill with Sox,” Birmingham News, August 7, 1944: 15.

55 Lester, 228. The game’s promoters would not accede to Paige’s demand for more money even though Paige had said he would donate the extra cash to an Army or Navy charity of their choice.

56 Kelley credits Mathis with two all-star game victories in his book (p. 123) and several news articles initially named Mathis as the winning pitcher in 1944 (for one such account, see “West’s Negro Stars Defeat East, 7 to 4,” Chicago Tribune, August 14, 1944: 17); however, Jessup was the winner, and most news outlets and modern sources have correctly listed him as such (the Tribune soon corrected its error; see “Negro Giants Face Memphis Red Sox Today,” Chicago Tribune, August 20, 1944:25). It should also be noted that Mathis’ recollections again were in error in later years. In Mills’ book (p. 79), Mathis recalled teaming with Paige for a victory in the 1943 East-West game and being the winning pitcher of record in the 1944 game. However, Mathis did not play in the 1943 game, and Jessup was the winning pitcher in 1944; Mathis did become the winning pitcher in the 1945 game, but Paige did not participate in that one.

57 “Memphis Jolts Chicago, 3-2; 6-3/Red Sox Cop Two Games,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 26, 1944: 12.

58 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc., 1994), 521.

59 “Satchel Paige to Pitch for Elks Benefit July 22,” Detroit Tribune, July 14, 1945: 12.

60 Lester, 255.

61 “Royals, All-Stars Vie Again Tonight,” Los Angeles Times, September 27, 1945: 10.

62 “Pitchers Named for Negro Game,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, October 4, 1945: 14.

63 Riley, 521.

64 “Memphis Splits with Clowns,” Chicago Defender, April 27, 1946: 10.

65 Johnnie Johnson, “Monarchs Trim Red Sox, 3-0,” Chicago Defender, May 18, 1946: 11.

66 “Cleveland at Memphis July 7,” Chicago Defender, July 6, 1946: 11.

67 “Negro All-Stars Play Here on Tuesday Night,” Dayton (Ohio) Daily News, September 24, 1946: 21; William F. McNeil, The California Winter League: America’s First Integrated Professional Baseball League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2002), 229.

68 “Memphis and Barons Divide,” Chicago Defender, June 21, 1947: 11; “Monarchs vs. Clowns Sunday,” Chicago Defender, June 28, 1947: 19.

69 “Heavy Ticket Sale for 15th East-West Classic,” Chicago Defender, July 26, 1947: 11.

70 McNeil, 170.

71 Christopher Hauser, The Negro Leagues Chronology: Events in Organized Black Baseball, 1920-1948 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2006), 162.

72 Hauser, 163; “Cleveland Buckeyes Sign for Home Game Broadcast,” Atlanta Daily World, June 2, 1948: 5; “Memphis Divides with Cleveland,” Chicago Defender, June 12, 1948: 11; “Cuban-Kaycee Game Not First To Be Telecast,” Chicago Defender, May 13, 1950: 17.

73 “Mathis, Sharpe, Top Negro Stars, Join Club,” St. Joseph Herald-Press, July 31, 1948: 7.

74 “West and East Meet Today in Negro Baseball,” Chicago Tribune, August 22, 1948: 63; “Mathis Signs to Play with Auscos,” St. Joseph Herald-Press, August 24, 1948: 7.

75 “Mathis Signs to Play with Auscos.” The newspaper extolled Mathis’ virtues and noted, “A member of the Memphis staff for the past five years, his record thus far this year is 14 victories and five defeats. His best year was in 1944 when he won 22 and dropped but four for the southerners.”

76 “Auscos Walloped by South Bend Studebakers, 11 to 2 In M-I Fray/Slam 14 Hits, Nine Go for Extra Bases,” St. Joseph Herald-Press, August 27, 1948: 12; “Auscos Launch Final Week of Baseball Campaign/Grays Score Three in Ninth to Win, 8 to 7,” St. Joseph Herald-Press, August 30, 1948: 7; “Auscos-Michiana All-Stars Meet Tonight/Red Sox Beaten, 9-5 in M-I League Fray,” St. Joseph Herald-Press, September 1, 1948: 10.

77 “Negro Baseball Stars Play Here,” Monroe (Lousiana) News-Star, October 19, 1948: 11.

78 “Memphis Sox Begin Training,” Tampa Bay Times, March 21, 1949: 19.

79 “Barons, Memphis Split Doubleheader,” Alabama Tribune (Montgomery, Alabama), July 29, 1949: 7.

80 “Baltimore’s Pitching Tops Sox,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 27, 1949: 23.

81 “Satchel, Gene to Field Nines in Exhibition,” Muncie (Indiana) Star Press, October 13, 1949: 15; “Satchel Paige All Stars Vs. Memphis Red Sox (Advertisement),” Jackson (Tennessee) Sun, October 14, 1949: 6.

82 “Chiefs Open S-M Play Sunday Against Waseca,” Winona (Minnesota) Republican-Herald, May 12, 1950: 18.

83 “Wieczorek Bops Grand-Slammer in 9 to 8 Defeat,” Winona Republican-Herald, May 24, 1950: 16.

84 Augie Karcher, “Behind the Eight Ball,” Winona Republican-Herald, July 1, 1950: 10.

85 Augie Karcher, “Behind the Eight Ball,” Winona Republican-Herald, August 8, 1950: 13.

86 “Eagles Play Monterrey 9 in Cap Park,” Galveston Daily News, October 6, 1950: 21.

87 “Easter’s All-Stars Play Here Tonight,” Galveston Daily News, October 22, 1950: 16.

88 “Robinson Bats Home Only Tally/Gumpert Scores Pitching Victory,” Richmond (Virginia) Times-Dispatch, October 14, 1951: 82; “Campanella Stars Defeat Carolina Aces by 5 to 2,” Charlotte Observer, October 11, 1952: 16; “Campanella’s Squad Scores 8-0 Victory,” Corpus Christi Caller-Times, October 21, 1952: 22; “All-Stars of Diamond to Play Monday,” Waco News-Tribune, November 2, 1952: 27.

89 Mills, 83.

90 Mills, 83.

91 Riley, 522.

92 Malcolm Moran, “A Sentimental Journey for the Negro Leagues,” New York Times, June 5, 1989: C3.

93 Mills, 83.

94 “Trail blazers/Robinson, Negro Leagues honored by Brewers,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, July 19, 1997: 27, 33.

95 Don Wade, “First Inductees of Memphis Sports Hall of Fame enjoy ‘special’ night,” https://dailymemphian.com/article/8092/First-inductees-of-Memphis-Sports-Hall-of-Fame-enjoy-special-night, accessed May 1, 2020.

96 Thom Loverro, The Encyclopedia of Negro League Baseball (New York: Checkmark Books, 2003), 193. Officially, Mathis had a 2-2 record against Paige, but Gulley may have credited Mathis’ 10-inning victory over the duo of Paige and Johnson in New Orleans in 1942 as a triumph over Paige; however, as has been covered previously in this article, Johnson was credited with the loss in that game.

Full Name

Verdell Jackson Mathis

Born

November 18, 1913 at Crawfordsville, AR (US)

Died

October 30, 1998 at Memphis, TN (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.