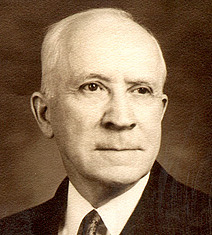

J.L. Wilkinson

J. Leslie Wilkinson (1878-1964) was one of the most respected and influential figures in the history of Black baseball. His trailblazing role in helping to found the Negro National League in 1920, in addition to his establishing and operating the renowned Kansas City Monarchs for many years, earned him a plaque in the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006.

J. Leslie Wilkinson (1878-1964) was one of the most respected and influential figures in the history of Black baseball. His trailblazing role in helping to found the Negro National League in 1920, in addition to his establishing and operating the renowned Kansas City Monarchs for many years, earned him a plaque in the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006.

Wilkinson was born on May 14, 1878, in Algona, Iowa. He was the oldest child of Myrta “Mertie” Harper and John J. “J.J.” Wilkinson. His father was a teacher and superintendent of schools in Algona and participated in local politics. J.J. also served as president of Northern Iowa Normal School in Algona before moving his family to Omaha, Nebraska, and then to Des Moines, Iowa, where he became a manager in the Iowa National Life Insurance Company.1

Young J.L. learned the basics of baseball on the sandlots of Algona. He became an accomplished pitcher on an Omaha high-school team and later attended Highland Park Normal College in Des Moines, where he was one of the school’s leading pitchers.

Beginning in 1895, Wilkinson played semipro baseball for more than a decade, at first using the pseudonym “Joe Green” to protect his amateur standing. In the 1900 census J.L. was listed as a clerk at Chase Brothers, a leading Des Moines grocery store, although his real job was probably pitching for the store’s outstanding semipro baseball team. Des Moines newspapers hailed his skills on the mound. But in 1900 a broken wrist brought his dreams of a professional pitching career to a sudden halt.

In 1904 Wilkinson joined a new semipro team organized by Hopkins Brothers Sporting Goods in Des Moines. The club traveled throughout Iowa, beating almost all comers and, at one point, winning 17 of 18 games. Although he no longer pitched, Wilkinson played a fair game at shortstop.

The Hopkins team closed its 1904 season with a doubleheader against the all-Black Buxton Wonders. Buxton was a thriving coal-mining community in southeastern Iowa with a population of 2,700 Blacks and 2,000 whites. Wilkinson undoubtedly took note of the racial harmony in Buxton, which was evident in the large, integrated crowd at the games. Hopkins Brothers won the first contest, and the Wonders (augmented by several Black players from Chicago) took the second.

Wilkinson became the Hopkins captain and manager in 1905. The decision to go into management may have been made after a Des Moines sportswriter opined that he was a good defensive shortstop and played with his head but that he fell short as a hitter.

Wilkinson’s promotional acumen was soon evident. He took his Hopkins teammates on the road throughout Iowa, Minnesota, and the Dakotas, booking games against local teams in small towns. To increase attendance, Wilkinson came up with a new gimmick in 1907. He scheduled games that coincided with fairs, carnivals, festivals, and reunions. When people came to the games, they saw a juggernaut. In one stretch in 1908, the Hopkins team won 31 of 33 games.

Wilkinson was married in 1908. According to his daughter, Gladys, the parents of his wife, Bessie, were not pleased that she had taken up with a “baseball man.” They were devout Methodists who considered baseball players to be ruffians. However, Bessie grew to love the game and traveled with her husband on barnstorming tours. In addition to Gladys, J.L. and Bessie had a son, Richard.

At the end of the 1908 season, Wilkinson disbanded the Hopkins men’s team and created a barnstorming club of “Bloomer Girls” named the Hopkins Brothers Champion Lady Baseball Club. He recruited the best female baseball players he could find, including a superstar from the Boston Bloomer Girls, who played under the name Carrie Nation, the famous ax-wielding temperance activist and suffragette. Wilkinson augmented the team with at least three male players, including a catcher who was also a wrestler and who was willing to take on all comers in the small towns in which they played. Beginning in June 1909, the club traveled in style when Wilkinson leased a Pullman Palace railroad car for their barnstorming tours. In addition to the players and a bulldog mascot, he took along a portable ballpark, consisting of a canvas fence 14 feet high and 1,200 feet long, and a canopy-covered grandstand that could seat 2,000 fans. The next year he added a lighting system for use in night games. It would not be the last time he experimented with lights.

Wilkinson continued to be a baseball innovator. Although ethnic teams, such as African American clubs, were popular in the early 1900s, no one had ever fielded a team made up of different nationalities and ethnic groups. Wilkinson recruited Native Americans, African Americans, Chinese, Japanese, Hawaiians, Frenchmen, Cubans, Filipinos, Scotsmen, Germans, and Caucasian American players. Fittingly, he called his new team All Nations. Beginning in May 1912, All Nations toured the country all the way to the West Coast and back to Iowa. In 1913 the team won 119 games and lost 17. After the 1915 season Wilkinson moved the All Nations operation to Kansas City. The club flourished there in 1916 but was disbanded in 1918 because some of the players had been drafted to serve in World War I.

After the war Wilkinson, who was now living with his family in Kansas City, revived the All Nations club. During its tenure All Nations featured several players of major-league caliber. Among them were African Americans John Donaldson and Frank Blattner, as well as Cubans Jose Mendez and Cristóbal Torriente.

Donaldson was a left-handed pitcher with a good fastball and changeup, outstanding control, and a hard, sharp-breaking curve. In 1916-17 Donaldson pitched in 10 games with All Nations, striking out 64. Wilkinson told reporters that Donaldson was one of the greatest pitchers who ever lived, White or Black. Mendez, known as the “The Black Diamond,” was one of the first internationally known Cuban players. He had a blazing fastball and a sharp curve. Mendez was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame with Wilkinson in 2006. Torriente was perhaps the most famous Cuban player of his era. He was a left-handed power hitter who was also an effective basestealer, and an outstanding center fielder with excellent range and a strong, accurate arm. He was also inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006. In an effort to make the All Nations team appear more diverse, Blattner played under the name “Blukoi” and often claimed he was Hawaiian. At other times Blattner was introduced as a full-blooded American Indian.

Another All Nations player of note was Goro Mikami, an outfielder, who joined the team in 1912, as the first-ever Japanese professional baseball player. Other All Nations players who excelled were two right-handed pitchers, Bill “Plunk” Drake and Wilber “Bullet Joe” Rogan. Rogan, considered by many baseball historians to be one of the best pitchers of all time, was inducted into Cooperstown in 1998.

The All Nations team showed that Wilkinson was well ahead of his times as a baseball promoter and advocate of racial integration. In an era when the racist movie The Birth of a Nation was so popular that it was shown by President Woodrow Wilson in the White House, and three decades before the breaking of the color barrier in the White major leagues, Wilkinson’s All Nations proved that an interracial team could not only succeed but flourish.2

In 1920 another opportunity presented itself to Wilkinson when Rube Foster took the lead in organizing the Negro National League. The organizational meeting was held at the Paseo YMCA in Kansas City in February 1920, and the first games were played in May. Wilkinson, joined by a Kansas City, Kansas, businessman, Thomas “T.Y.” Baird (who played a largely behind-the-scenes role), formed a club called the Kansas City Monarchs and applied for membership in the new league. At first Foster was reluctant to accept White ownership of a club in his circuit, but he relented because of Wilkinson’s reputation for integrity and fairness. In fact, Wilkinson earned such respect from his fellow owners that he was named the league’s secretary. Together, he and Foster led the new league into a decade of success and prosperity. Wilkinson also tapped two African American leaders to represent the team in Kansas City’s Black community: Quincy Gilmore (who served as the team’s traveling secretary and publicist) and Dr. Howard Smith, a physician and superintendent of Kansas City’s Black hospital. Serendipitously, the year before the Monarchs were founded, an African American weekly, the Kansas City Call, began publication. The Call provided coverage of the Monarchs and other Negro Leagues teams, while dailies like the Kansas City Star largely ignored them.

Wilkinson took some of the best players from his All Nations team to fill his new club’s roster, including Donaldson, Mendez, and Blattner. (Torriente went to the rival Chicago American Giants but joined the Monarchs in 1926.) Acting on a tip from a friend, Kansas City native Casey Stengel, Wilkinson added some players from the 25th Infantry Wreckers, an all-Black US Army team. Included in this group were Rogan, power-hitting outfielder Oscar “Heavy” Johnson, talented first baseman Lemuel “Hawk” Hawkins, crafty southpaw Andy Cooper (who was inducted with Wilkinson into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006), and shortstop Dobie Moore. Moore, known as The Black Cat, won the NNL batting title in 1924 with a .453 average and was considered the top shortstop in the league for six years until his career was cut short early in the 1926 season. At a celebration after a ladies day game on May 17, Moore was shot in the leg by a woman who claimed he had assaulted her. Moore then broke his leg jumping from a window to escape from her.

Wilkinson, affectionately called “Wilkie” by his players, fans, and fellow executives, built the Monarchs into the most successful NNL club of the 1920s. The team won the league pennant four times in the decade — 1923, 1924, 1925, and 1929. In 1924 the Monarchs played the Eastern Colored League champion Hilldale club in the first Colored World Series. With the hard-fought best-of-nine series tied at four games, José Mendez, told by doctors he was too ill to play, pitched a three-hit shutout and Kansas City captured the title. In 1925 the league played a split season and the Monarchs defeated the St. Louis Stars for the championship. The Monarchs lost the 1925 World Series to Hilldale, partly because ace pitcher Bullet Joe Rogan was sidelined by a freak accident. In 1926 Wilkinson purchased the first of a number of buses, touring cars, and trailers (with portable kitchens) that the Monarchs used on their barnstorming tours. With these vehicles, Wilkinson was able to schedule games in towns without rail connections. The players also slept in the buses when, often because of Jim Crow restrictions, other accommodations were not available.

Wilkinson tapped Mendez to manage the Monarchs their first two seasons. Another pitcher, Sam Crawford, was the skipper for a portion of the 1921 season and the 1922 and 1923 campaigns. Mendez resumed the helm during the 1923 season and continued as skipper through the 1925 season. Rogan was Monarchs manager for the rest of the seasons of the decade. Among the not-yet-mentioned stalwart players Wilkinson signed for the Monarchs during the 1920s were Roy “Bubba” Johnson, Carroll “Dink” Mothell, Hurley McNair, Otto “Jaybird” Ray, Zack “Hooks” Foreman, George “Tank” Carr, Clifford “Cliff” Bell, William Bell, Newton “Newt” Allen, Walter “Newt” Joseph, Bartolo Portuando, Frank Duncan, Alfred “Army” Cooper, Rube Currie, Chet Brewer, and Eddie “Pee Wee” Dwight.

As early as 1921 Wilkinson booked the first of what would become many games between the Monarchs and all-star teams of major leaguers that featured legends such as Babe Ruth, Dizzy Dean, Stan Musial, and Bob Feller. The Monarchs won the majority of these interracial contests, but the substantial sums taken in at the gates were what counted most.

The Great Depression of the 1930s wreaked havoc upon baseball in general and Black baseball in particular. The Eastern Colored League had folded in 1928. The Monarchs withdrew from the NNL after the 1930 season and the league disbanded in 1931. The Monarchs survived because of Wilkinson’s vision and ingenuity. In 1929 he commissioned an Omaha company to design a portable lighting system for night games. Wilkinson had experimented with baseball under the lights before, but this system was far better. Powered by a 250-horsepower motor and a 100-kilowatt generator, the equipment illuminated lights atop telescoping poles extending 40 feet above the field. With the support of his wife, Bessie, Wilkinson mortgaged everything he owned to purchase the system, and his gamble paid off. Wilkinson believed that just as talkies saved the movies, lights would save baseball, and he was right. The Monarchs’ first night game was played in Enid, Oklahoma, on April 28, 1930. Within a few months, night games proved to be a huge success and Wilkinson quickly recouped his initial investment.

From 1931 through 1936 the Monarchs were an exclusively barnstorming team. They often played in daylight and after dark on the same day and became the most popular touring team in the nation. Frequently they were accompanied by the bearded House of David, another hugely successful barnstorming club. In order to enhance revenue, the Monarchs sometimes rented the lighting equipment to their friendly rivals. Among the standout players for the Monarchs during these barnstorming seasons were Bullet Joe Rogan (who managed the team in 1931, 1933, and 1934), Dink Mothell (manager in a portion of the 1930 season and 1932), Newt Allen, Newt Joseph, John Donaldson, Norman “Turkey” Stearnes, Frank Duncan, Chet Brewer, Army Cooper, Andy Cooper (who was skipper during the 1936 and 1937 seasons), Willie Foster, George Giles, Willie Wells, James “Cool Papa” Bell, Quincy Trouppe, Rube Currie, Frank Duncan, Pee Wee Dwight, Eldridge “Ed Chill” Mayweather, and Willard Brown. Sam Crawford was manager in 1935. In addition to Rogan and Andy Cooper, National Baseball Hall of Fame inductees from this group were Bell (1974), Foster (1996), Wells (1997), Stearnes (2000), and Brown (2006).

In 1933 the Negro National League was revived, but it was no longer under the leadership of Wilkinson or Foster, who had died in 1930. In 1937 Wilkie helped form a new circuit, the Negro American League and served as the league’s first treasurer. His Kansas City Monarchs continued to be a power in the new circuit. They won the NAL pennant in 1937, 1939, 1940, 1941, 1942, and 1946. In 1942 they swept the Homestead Grays in four games in the first Colored World Series since 1927. The 1942 Series featured an encounter between two of the legends of the game, Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson. In an example of his generosity and in one of the early instances of revenue-sharing, Wilkinson divided the Monarchs’ portion of the Series gate among the players. The Monarchs lost the 1946 World Series to the Newark Eagles in seven games.

Between 1937 and 1948 (the last year Wilkinson owned the Monarchs), prominent players included Andy Cooper (also manager, 1937-40), Ed Mayweather, Newt Allen (skipper during the 1941 season), Willard Brown, Byron “Mex” Johnson, Pee Wee Dwight, Bullet Joe Rogan, Hilton Smith, John Markham, John “Buck” O’Neil (manager in 1948), T.R. “Ted” Strong, Turkey Stearnes, Frank Duncan (at the helm, 1942-47), Leroy “Satchel” Paige (inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1971), Chet Brewer, Clifford “Connie” Johnson, Jack Matchett, Booker McDaniel, William “Bonnie” Serrell, Jesse Williams, Henry “Hank” Thompson, Ted Alexander, James “Lefty” LaMarque, Jackie Robinson (the first African American inductee at Cooperstown, in 1962), Elston Howard, and Earl Taborn.

The Monarchs were so dominant in the late 1930s and early to mid-1940s that they became known approvingly as the Negro Leagues’ version of the New York Yankees. The best players wanted to play on a winning team. Also helpful were Wilkinson’s reputation for fairness and integrity and his efforts to secure proper accommodations for his players during the Jim Crow era. A mutual respect developed between the players and the ownership of the Monarchs. Wilkinson also expected his players to be wholesome ambassadors for the Monarchs and Black baseball. He bought suits for ballplayers and expected them to wear them in the community. In addition, he often took care of their medical needs. Monarchs players were treated as celebrities, particularly in the area around 18th and Vine in Kansas City (where the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum is now located), and they could often be seen in venues such as the famed Rose Room of the Streets Hotel alongside stars like Count Basie.

Two of Wilkinson’s stellar achievements during this period were the resurrection of the career of Satchel Paige and the signing of Jackie Robinson. The two players were quite different in background and temperament, but they shared one attribute: tremendous talent. Paige had been an outstanding pitcher for many years, and Wilkinson had “rented” the lanky right-handed hurler to play in exhibition games with the Monarchs on a number of occasions. Wilkie and Satchel got along well despite Paige’s reputation for being hard to manage. In 1938 Paige was banned for life from the Negro National League for contract-jumping. He joined the Mexican League, where he suffered his first sore arm in 12 years. Wilkinson was the only Negro Leagues executive willing to take a chance on Paige. He signed the wounded veteran to a team that he christened Satchel Paige’s All-Stars and sent them on a wildly successful barnstorming tour through the Northwest and Canada. By 1939 Paige’s arm had healed and, with Hilton Smith, he became the leading pitcher for the Monarchs in the NAL. Paige and Wilkinson developed a close bond. In commenting on how Wilkinson treated him, Paige said, “[T]hat’s how Mr. Wilkinson was. If you were down and needed a hand, he’d give you one.”3 Paige remained with the Monarchs until Bill Veeck signed him to a major-league contract with the Cleveland Indians in 1948.

Jackie Robinson had starred in baseball, basketball, track, and football at UCLA, earning a reputation as one of the best all-around athletes in the country. While serving in the Army and stationed at Camp Hood (now Fort Hood) in Texas, Robinson had the opportunity to play some baseball, and was spotted by Hilton Smith, who recommended him to Wilkinson. After his discharge from the Army, Robinson joined the Monarchs for the 1945 season, but he was with Wilkie’s team for only a few months. As is well known, Branch Rickey signed Robinson to break Organized Baseball’s color barrier on August 28, 1945. Rickey claimed that Robinson did not have a legitimate contract and paid nothing to the Monarchs for signing him to the Brooklyn Dodgers organization. Wilkinson graciously responded, saying: “Although I feel the Brooklyn club … owes us some kind of compensation for Robinson, we will not protest to Commissioner [Happy] Chandler. I am very glad to see Jackie get this chance and I’m sure he’ll make good. He’s a wonderful ballplayer. If and when he gets into the major leagues he will have a wonderful career.”4

Nearly blind and suffering from other ailments in 1948, Wilkie sold his interest in the Monarchs to his longtime business partner, Tom Baird, and retired from baseball. Wilkinson, however, had not lost his good business sense, and he arranged to receive a portion of any amount Baird received for selling a Monarchs player to the major or minor leagues if that player had been with the team while Wilkinson was still an owner. J.L. “Wilkie” Wilkinson died in a Kansas City nursing home on August 21, 1964. His remains rest in the Garden Mausoleum at the Mount Moriah Cemetery in Kansas City, Missouri. Many of the old Monarchs attended his funeral.

Years later Buck O’Neil, who had been his close friend since signing with the Monarchs in 1938, paid this tribute to Wilkinson: “[H]e “didn’t have a prejudiced bone in him. … While Wilkinson could have been lynched just for owning a Black ball baseball team, he never allowed the ugly racial prejudice of his day to keep him from doing what he loved and believed — Black baseball at its highest. J.L. Wilkinson, he looked down on no one and he brought out the best in everyone. That’s J.L. Wilkinson. … I love that man.”5

In addition to Robinson and Paige, a number of Monarchs who had played under Wilkie’s management of the team went into Organized Baseball, including Elston Howard, the first African American to play for the New York Yankees. Thirteen Monarchs players are in the National Baseball Hall of Fame: Ernie Banks, Cool Papa Bell, Willard Brown, Andy Cooper, Bill Foster, Jose Mendez, Satchel Paige, Jackie Robinson, Bullet Joe Rogan, Hilton Smith, Turkey Stearnes, Cristobal Torriente, and Willie Wells. Wilkinson joined them when he was inducted posthumously in 2006, His plaque at Cooperstown is inscribed as follows:6

LESLIE WILKINSON

“J.L.” “WILKIE”

KANSAS CITY MONARCHS, 1920-1948AN INNOVATIVE AND GENEROUS OWNER WHO FOUNDED AND OPERATED THE KANSAS CITY MONARCHS FROM 1920-1948. RESPECTED FOR HONESTY AND FAIRNESS WITH HIS PLAYERS. HIS MONARCHS DOMINATED BLACK BASEBALL, WINNING THE MOST LEAGUE TITLES AND TWO NEGRO LEAGUE WORLD SERIES CHAMPIONSHIPS. CREATED MULTI-RACIAL ALL-NATIONS BARNSTORMING TEAM THAT FLOURISHED FROM 1912-1918, THEN HELPED FOUND THE NEGRO NATIONAL LEAGUE IN 1920. DEVISED PORTABLE LIGHTING SYSTEM WHICH ALLOWED TEAMS TO PLAY NIGHT GAMES AND SURVIVE THE GREAT DEPRESSION. SENT MORE PLAYERS, INCLUDING JACKIE ROBINSON, TO MAJOR LEAGUES THAN ANY OTHER NEGRO LEAGUES OWNER.

Sources

In addition to the following sources listed below and cited in the Notes, the authors also consulted a number of web sites, including Ancestry.com, Baseball-Reference.com, www.baseballhall.org, www.entertainment, howstuffworks.com, www.iptv.org, and seamheads.com.

Clark, Dick and Larry Lester, eds. The Negro Leagues Book (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1994).

Heaphy, Leslie A. The Negro Leagues: 1869-1960 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2003).

Heaphy, Leslie A. Satchel Paige and Company: Essays on the Kansas City Monarchs, Their Greatest Star and the Negro Leagues (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2007).

Hogan, Lawrence. Shades of Glory: The Negro Leagues and the Story of African American Baseball (Washington, DC: National Geographic, 2006).

Johnson, Lloyd, Steve Garlick, and Jeff Magaliff, eds. Unions to Royals: The Story of Professional Baseball in Kansas City (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1996).

Peterson, Robert. Only the Ball Was White: A History of Legendary Black Players and All-Black Professional Teams (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1970).

Riley, James. The Biographical Encyclopedia of Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll and Graf, 1994).

Tygiel, Jules. “Black Ball,” in John Thorn et al., eds., Total Baseball: The Ultimate Baseball Encyclopedia (Wilmington, Delaware: Sport Media, 2004).

Young, William A. J.L. Wilkinson and the Kansas City Monarchs: Trailblazers in Black Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2016).

Notes

1 Ralph J. Christian, “Wilkie: James [sic] Leslie Wilkinson and the Iowa Years,” Iowa Heritage Illustrated (Spring 2006). This is by far the most thorough account of Wilkinson’s early life and start in baseball.

2 Timothy Gay, Satchel, Dizzy and Rapid Robert: The Wild Saga of Interracial Baseball Before Jackie Robinson (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2010), 25-26.

3 Leroy “Satchel” Paige, as told to David Lipman, Maybe I’ll Pitch Forever; A Great Baseball Player Tells the Hilarious Story Behind the Legend (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993 [1962]), 123-31.

4 Janet Bruce, The Kansas City Monarchs: Champions of Black Baseball (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1985), 112. This is the first comprehensive survey of the Monarchs, drawing on interviews with players and their families as well as the families of J.L. Wilkinson and Tom Baird.

5 Sam Mellinger, “J.L. Wilkinson: He Was a Man Apart,” Kansas City Star, July 30, 2006: C1, C12.

Full Name

James Leslie Wilkinson

Born

May 14, 1878 at Algona, IA (US)

Died

August 21, 1964 at Kansas City, MO (US)

Stats

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.