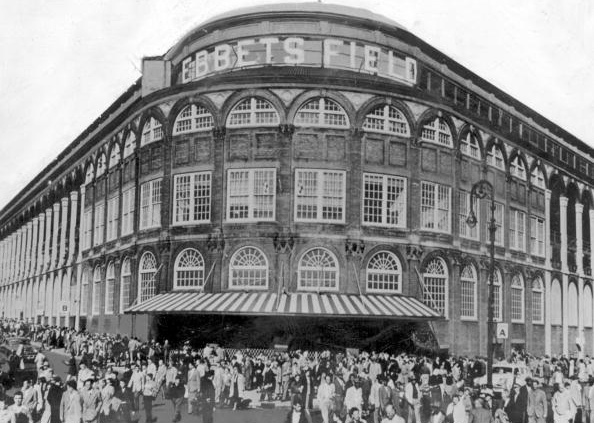

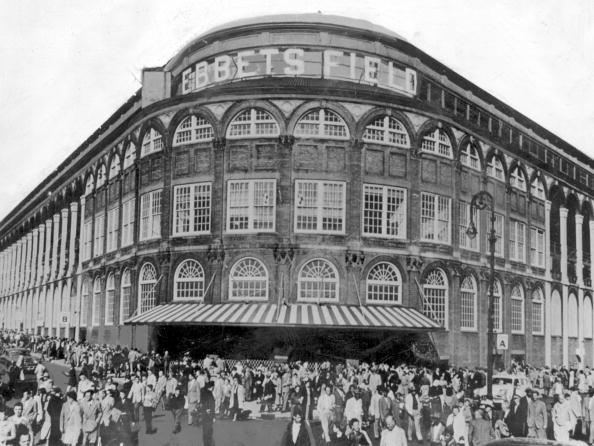

Twilight at Ebbets Field

This article was written by Rory Costello

Ebbets Field has been gone for more than half a century, but the place still has a remarkable grip on our consciousness. At least three books have been devoted to the lovable old ballpark in Crown Heights.1 Yet even these in-depth works don’t shine much light on what happened after the Dodgers left Brooklyn. They touch briefly on some teasing references to post-Dodger history, but there’s more to this period than mere footnotes. It is a buried chapter of stadium lore — featuring two Hall of Fame stars.

This article does not re-examine whether club owner Walter O’Malley or New York City power broker Robert Moses could have kept the club from going west. By late 1957, it was a foregone conclusion. In major-league terms, Brooklyn had been reduced to a bargaining chip or at best a fallback option in case O’Malley’s negotiations with Los Angeles blew up. People like Abe Stark — the local tailor (“Hit Sign, Win Suit”) turned City Council president — were hoping against hope.

What many don’t recall is how long Ebbets clung to life. Even people who are Brooklyn to the bone, like journalist Pete Hamill, were prone to misty memory. On his website, Hamill once wrote, “Within a year after the Dodgers lammed to Los Angeles, Ebbets Field was smashed into rubble.” Not true — the Bums played their last home game on September 24, 1957, but the wrecking ball did not swing until February 23, 1960.

To recap, the Dodgers played the ’57 season on the first year of O’Malley’s three-year leaseback deal with developer Marvin Kratter, who had bought the property for $3 million on October 30, 1956. Kratter hinted in October ’57 that another club might relocate to Ebbets.2 However, that may have been just a P.R. red herring. In 1958, the new Dodger home was the Los Angeles Coliseum; meanwhile O’Malley was also paying for three other parks: Wrigley Field in L.A., Roosevelt Stadium in Jersey City (where the Dodgers had played seven “home” games in’56 and eight in ’57), and Ebbets. The cagey Irishman estimated his carrying costs on the Brooklyn facility at $170,000 a year — $80K in rental, $40K in maintenance, and $50K in real estate taxes.3 So in an effort to cut his losses, he subleased.

Enter Robert A. Durk, a local homebuilder who thought he saw an opportunity. Durk, aged 36 in early 1958, was the frontman for Ebbets Field Productions. This venture had grand plans for various sporting attractions and other events; rent would be paid on a percentage basis. One such hope was to bring in the Yomiuri Giants, Japan’s version of the Yankees, to play a Latin American team.4

This idea was years ahead of its time, but it didn’t pan out. Instead, a demolition derby paid a visit. Jack Kochman’s Hell Drivers apparently were hell — on the Ebbets Field turf. The New Jersey-based troupe put on two performances a day from May 30 through June 1. It replaced the Dick Clark Caravan Tour after bad publicity from an alleged rock ‘n’ roll riot in Boston caused the host of American Bandstand to postpone his shows.5

Kochman’s Auto Thrill Show survived through 2004, as did the man himself, who died at the age of 97. Yet for better or worse, there are likely no other records of the “Smashing! Crashing! Racing!!” (as the spectacle was billed in a New York Daily News ad). Charlie Belknap, who took over the business in 1989, said, “Jack probably would have remembered those shows because they were in the metropolitan area. But he wouldn’t have kept programs or anything like that. He’d have said, ‘That’s clutter — get rid of it.’”6

The available evidence shows that Ebbets Field Productions staged only one more event: the Hamid-Morton circus, also booked for two daily performances from June 29 through July 12. Robert A. Durk Associates, Inc. (liabilities: $86,828 — assets: $9,110) declared bankruptcy in August 1958.7 Durk, who later became an ad man in Connecticut, then faded from the scene. He died in 1988.

The most popular post-Dodger activity at 55 Sullivan Place was soccer. On May 25, 1958, 20,606 spectators braved the rain to see Hearts of Midlothian (Scotland) beat Manchester City (England) 6-5 on a muddy pitch. Had the weather been better, the crowd might have approached capacity. One day short of a year later, Dundee and West Bromwich Albion drew 21,312 — the best turnout of the twilight years. There were 15 programs in 1959, played both in the afternoon and under the lights. New York Hakoah, a Jewish-oriented team in the old American Soccer League (ASL), moved in from the Bronx. A strong array of international squads — from Italy, Spain, Poland, Sweden, and Austria, as well as the U.K. — built the audience for the ASL.

At first it might seem surprising to see what a drawing card this sport was — it did better than a lot of Dodgers games toward the end. But it is less remarkable in view of Brooklyn’s historically large and varied immigrant population. Plus, there was an echo of when Dodger fans occasionally crossed the line from avid and boisterous to riotous. Hundreds of unruly Napoli partisans erupted on the field to attack the officials on June 28, 1959. A patrolman was also knocked out with a linesman’s flag.8

Although Ebbets had hosted a good deal of boxing and American football in its past, neither sport was visible there during 1958-59. Brooklyn was considered a possibility for the AFL as that rival league was forming in 1959.9 Instead, the New York Titans (later the Jets) went with the Polo Grounds. Other ideas were merely fanciful. In July 1959, Abe Stark — briefly Acting Mayor in Robert Wagner’s absence — injected himself into a racial debate over the West Side Tennis Club in Forest Hills. Dr. Ralph Bunche, the eminent statesman and civil rights leader, and his son ran into the club’s color barrier. Stark postured against Forest Hills and announced that he had gained permission from Marvin Kratter to use Ebbets free of charge for Davis Cup matches and the National Championship.10 But the flap died down within a week, and with it Stark’s sentimental hope.

At its core, Ebbets Field was still a baseball venue. In the spring of 1958, Long Island University played six home games there and St. John’s played four, under the auspices of the Dodgers. LIU coach William “Buck” Lai, a Dodgers scout and instructor at the Dodgertown Camp for Boys in Vero Beach, was instrumental. His wife Mary stated, “Buck knew the O’Malleys well. Therefore he was able to arrange for the Blackbirds to play at Ebbets Field before it was demolished. He was very proud that his college team’s home field was a major league field.”11 Then in ’59, LIU returned for one more, while St. John’s played two.

Unfortunately, these matches weren’t much of a draw — especially the first year, most Dodger fans were still in shock or mourning. College ball was a pretty thin substitute.

However, the St. John’s roster boasted a future big-leaguer. Brooklyn-born infielder Ted Schreiber hit a game-winning two-run homer at Ebbets on April 24, 1958; in 1963, he made 55 plate appearances for the New York Mets.12 Decades later, Schreiber (who went to Ebbets three or four times a year growing up) had clear recall:

“I remember it almost like it was yesterday. I just got through basketball season and I was struggling for hits. Most of my career, I never saw the ball hit the bat. But a lefty was pitching, so the angle was good, and the ball was out in front of the plate. My concentration was so keen, I didn’t look up, I was running hard to first base. Then I heard a rattle, and I knew it had to be the ball in the seats. The crowd was just a handful, people who loved college ball — that time of year wasn’t conducive to real good baseball.

And you know what was special? The field was so smooth! The regular places I played in Brooklyn, the Parade Grounds was good, but get in front of a ball in Marine Park, you deserve combat pay. I was impressed. As soon as you come out of the tunnel, you see the lights and it takes hold. It was very exciting to be on a major-league field.”13

At least one other future major-leaguer performed at Ebbets during this period: infielder Chuck Schilling of Manhattan College. Rutgers was coached by a former big-leaguer, George Case. Al Ferrara, like Schreiber a Brooklyn boy, went to LIU in 1958 — but never played baseball for the Blackbirds before turning pro in the spring of 1959.14

College baseball at Ebbets Field, 1958-59

| Date | Score |

|---|---|

| 4/5/58 | UConn 7, LIU 6 |

| 4/9/58 | LIU 11, Adelphi 4 |

| 4/10/58 | Rutgers 4, St. John’s 3 |

| 4/24/58 | St. John’s 2, Manhattan 1 |

| 4/30/58 | St. John’s 4, Hofstra 0 |

| 5/1/58 | NYU 3, St. John’s 0 |

| 5/2/58 | Fairfield 6, LIU 4 |

| 5/9/58 | LIU 7, Bridgeport 5 |

| 5/12/58 | LIU 3, NY Maritime 1 |

| 5/17/58 | LI Aggies 5, LIU 3 |

| 4/18/59 | Manhattan 5, St. John’s 3 |

| 4/25/59 | St. John’s 11, Manhattan 0 |

| 5/6/59 | LIU 7, Queens College 6 |

Source: New York Times; Washington Post, Times Herald

College and high-school players also took part in drills and some games at Ebbets Field in 1959. These were to select players and tune up for the Hearst Sandlot Classic between the New York Sandlot Stars and the United States All-Stars. (The age limit was 18 and under.) Starting on July 29, 14 practice sessions were held at Ebbets to select the N.Y. Stars, under the direction of former big-league star Tommy Holmes, who’d been named that April to head the New York Journal-American sandlot program.15 Two future big-leaguers made the cut: Billy Ott, who enjoyed two brief stints in the outfield with the Chicago Cubs in 1962 and 1964, and pitcher Larry Bearnarth, another early Met who later became a major-league pitching coach.

In the first tune-up game, on August 11, Holmes’s squad faced the Los Angeles Dodgers Eastern Rookie Stars, a touring amateur team managed by scout John Carey. The Dodger Rookies, won, 2-1. Zack Finkelberg, who’d played on the freshman team for Queens College that spring, had their biggest hit. He homered over the 55-foot-high wall in right field, well above the Schaefer beer sign. It landed on Bedford Avenue shortly before noon. The N.Y. Stars were experimenting with three new pitchers and some key players were participating in other tournaments. The box score shows that Ott and Bearnarth did not play at Ebbets on August 11, if indeed they were even present.16

The U.S. Stars, managed by Oscar Vitt and Buddy Hassett, played the Dodger Rookies at Ebbets on August 14 and August 15. The U.S. Stars won the first game, 5-4, and the Dodger Rookies won the second, 7-1 (box scores are not presently available). In one pregame practice, future big-leaguer Ernie Fazio homered for the U.S. Stars.17 The U.S. Stars also worked out at Ebbets on August 17, the day before the Classic itself was held at Yankee Stadium.18 Five other men on that roster besides Fazio eventually reached the majors: Wilbur Wood, Darrell Sutherland, Fritz Fisher, Glenn Beckert, and Bobby Guindon.

Stepping down another level, high-school games still took place at Ebbets too. The Dodgers conducted tryouts, with Tommy Holmes and various scouts looking over the prospects.19 They also sponsored the Public School Athletic League finals. On June 23, 1958, Martin Van Buren High of Queens defeated Curtis High of Staten Island 5-3.20 The Curtis team included a future major-leaguer, catcher Frank Fernandez, plus an infielder named Jack Tracy who made it to Triple A for several years.21 The next year, on June 5, Roosevelt High (Bronx) was the champ, and Curtis once more the runner-up, in a 6-5 battle before a crowd of 4,000.22

Going younger still, there is a nice anecdote about Babe Ruth ball. Paul Jurkoic was born in 1946 and grew up on Governor’s Island when it was an Army post. He knew it must have been the summer of 1959 when he came to Brooklyn, representing Fort Jay as part of an “All-Star Grasshopper” game — the basepaths were 90 feet long, not the Little League distance. Jurkoic still had vivid memories of that special day:

“The game was attended only by the family and friends of the players — a very small crowd indeed — maybe a few hundred. I don’t remember ever being in the locker room (disappointment!), so I suspect we traveled to and from the game in uniform. What I most remember was that the field was still very well kept, even though the Dodgers weren’t there anymore.

The infield grass was very green and healthy, and was mown short — like a golf fairway, and there were no pebbles or other obvious imperfections on the dirt part. This was like playing in heaven for us, because although the Army did a pretty good job of maintaining the field we played on (which was also used by the soldiers, I believe), it was not up to Major League standards. I was struck by the Spartan appearance of the dugout. I had thought that a big-league dugout would be somehow more fancy than it was. I also have an impression about the telephone that the managers used to call the bullpen — it was missing, but the wires were hanging out of the wall where it had been. It was definitely a thrill for all of us to play in a real big league stadium.”23

That game took place on August 22, 1959, just days after the tune-ups for the Hearst Sandlot Classic. It was a preliminary to a benefit match, held for the family of Charley Russo, a Dodgers scout who had died not long before. The Dodger Rookies were in action again. Assisting manager John Carey was Rudy Rufer, briefly a New York Giant in 1949-50. Hank Majeski was also involved with that team.24

The opponents were the Brooklyn All-Stars, another squad of top high school and college youths playing in the local sandlot leagues. Their manager was Steve Lembo, a catcher who’d played in seven games for the Dodgers in 1950 and 1952. The Brooklyn native then became an instructor at Dodgertown (he also scouted for the team for many years). Lembo had at least one future big-leaguer on his squad, pitcher Larry Yellen.25

Yet the most intriguing baseball action during the “twilight era” had fallen into total obscurity until research for the original version of this article unearthed it. A team called the Brooklyn Stars played at Ebbets in 1959. Their sponsor was one of “The Boys of Summer” — Roy Campanella, about 18 months after the auto accident that made him a paraplegic.

The Stars first came to this author’s attention in 1999 as a side note while writing the history of baseball in the Virgin Islands. One key source, a St. Croix native named Osee Edwards, also mentioned that he played for this semi-pro squad of black and Latin players. Osee worked as an X-ray technician in a Brooklyn hospital. He and his teammates advertised their games around the community, posting flyers in places like barbershops. He talked about Campy as well as facing another Dodger hero of the ’50s, Joe Black. Two years after Joe’s last major-league appearance, the first black pitcher to win a World Series game was a schoolteacher in his hometown of Plainfield, New Jersey. But he still hurled on occasion for a local team called the Newark Eagles.26 That team was a namesake of the Negro League franchise of 1936-48, whose Brooklyn forerunner played one year at Ebbets in 1935.

A letter seeking confirmation went out to Mr. Black shortly thereafter, but his brief reply was a damper. He pooh-poohed the idea that his old batterymate could have been involved. However, the newspaper archives show that his memory was not as clear as Osee’s. Roy Campanella was a surprisingly busy man after recovering from his accident. He attended all three Yankees home games during the 1958 World Series.27 That prompted U.S. Congressman Francis E. Dorn of Brooklyn to suggest a “Campy Day” at Ebbets, featuring a Dodgers-Yankees charity game after the Series ended. However, that appears to have been another bit of wishful thinking.28

After Campanella got out of the hospital for good in November 1958, his health was delicate, but he was still tending to his business ventures and the misadventures of his wayward stepson David. He attended spring training at Vero Beach in 1959 and went out to Los Angeles for the big night in his honor at the Coliseum on May 7. He appeared at Yonkers Raceway on July 1. In August, he even acted in an episode of the TV show Lassie. The article about the Charley Russo benefit mentioned the possibility that even in his wheelchair, Campy might serve as third-base coach (concrete evidence of this is lacking).29

Among all these other activities, Campanella fit in the formation of a ballclub at his old home field.30 Other Stars opponents included the Gloversville Merchants, who represented the leather-goods town on the southern fringe of Adirondack Park. They and the Newark Eagles met at old Hawkins Stadium in Albany, which by coincidence was also razed in 1960. Campy’s club often played in doubleheaders with teams such as the Memphis Red Sox from the Negro American League. The Negro Leagues, another institution on its last legs, would limp on through one more season.

But Ebbets Field had one last pro baseball hurrah — built around a genuine icon. On August 23, 1959, none other than Satchel Paige was the main attraction in a doubleheader that drew 4,000 fans. Barnstorming with the Havana Cubans, he gave his age as “somewhere between 40 and 60.” The Kansas City Monarchs topped the Stars 3-1 in the opener. Then Satch — wearing a Chicago White Sox uniform lent to him by former employer Bill Veeck — came on to strike out four in a three-inning start. The master allowed three runs, but only one was earned. He gave up a homer when he got cute and tried to sneak a second blooper pitch by Monarchs player-manager Herm Green.31

Roy Campanella’s Brooklyn Stars and the Negro American League at Ebbets Field, 1959

| Date | Action |

| 7/12/59 | Brooklyn Stars vs. Memphis Red Sox |

| Detroit Stars vs. Memphis | |

| 7/26/59 | Brooklyn Stars vs. Memphis Red Sox |

| Birmingham Black Barons vs. Memphis | |

| 8/2/59 | Brooklyn Stars vs. Detroit Stars |

| Detroit vs. Raleigh Tigers | |

| 8/23/59 | Kansas City Monarchs 3, Brooklyn Stars 1 |

| Havana Cubans 6, Kansas City Monarchs 4 |

Source: New York Times

Also in late August 1959, a few dozen teenage boys from Brooklyn had the opportunity to play a game at Ebbets. In 2007, one of them, Donald Reiss, recalled, “’Word spread through the neighborhood. . . It seemed one of the guys had an uncle who was, or knew, the head of groundskeeping, and it would be arranged to open the park for us. . . We were like kids in a candy store, but this was even better.”32

The Dodger Rookies returned on September 4, playing the Yonkers Chippewas to a 4-4 tie. The contest had been scheduled for Fleming Field in Yonkers but a conflict forced a switch to Ebbets. The game was called after seven innings to allow the “Chippies” time to get back home for an evening match.33

Finally, what may well have been the last baseball game of any kind at Ebbets Field appears to have taken place that month. It featured 12-year-olds in a youth league. The father of one of the boys, an amateur photographer named David Hirsch, took two photos of the lads on the field and seated in the dugout. The photos were inscribed “Sept. 59.”34

Yet even after the Cubans’ victory and the boys’ fun had faded into autumn, a flicker of life was still visible. The Hakoah soccer club scheduled a series of four Sunday doubleheaders. As it turned out, though, only three were played. Thus the last known sporting event at Ebbets took place on October 25, 1959.

Literally at the center of the action was Lloyd Monsen, Hakoah’s star striker and a member of the National Soccer Hall of Fame. Monsen was born in 1931 to Norwegian parents and grew up in the Bay Ridge section of Brooklyn. He stated, “The Ebbets Field soccer scene was a large part of my career.”35 For example, he scored a goal and two assists in the May 12, 1957 match between Hapoel F.C. of Israel and an ASL all-star squad, which also presented Marilyn Monroe and Sammy Davis, Jr. as entertainers.

A trove of photos and other items remained in Monsen’s possession, including a series of ASL newsletters. The November 1, 1959 issue explained what happened to that fourth Sunday outing. The games were originally slated for November 8, but were rescheduled for Thursday the 5th and then canceled.

“Not that the American Soccer League would like to leave the confines of Ebbets Field, but circumstances beyond our control make it so. For instance, the Sunday blue law that ball games not commence before 2 P.M., the end of Daylight Saving Time and no lights if a twin bill is scheduled, makes it imperative for the ASL to call it quits at the Brooklyn park. Maybe if Ebbets Field is still around next year and not knocked down for a housing project, the ASL will again consider staging shows there next spring.”

Monsen added, “Ebbets was better than any of the other stadiums we used. Crowds were in the thousands, quite good for us — but probably not good enough to support business.” He further recalled, “The dirt infield was still there in the right-hand corner of the field. The groundskeepers had leveled the mound and removed the rubber.”36

Indeed, as Ted Schreiber and Paul Jurkoic had observed, the most loyal Brooklyn foot soldiers were still at their posts. The most diehard retainer of them all has received scant mention in the many books about the team. Joseph Julius “Babe” Hamberger started as a clubhouse boy in 1921 and worked his way up to assistant traveling secretary. Although a number of club employees went west, Babe didn’t leave the only workplace he’d ever known. In April 1958, he said he’d miss the team, but added philosophically, “Oh well, I still have a job. With five kids, I’m still getting paid. And that puts meat on the table.”37 Hamberger served as superintendent in the twilight phase, along with a skeleton crew that included a part-collie, part-chow watchdog named Angel.

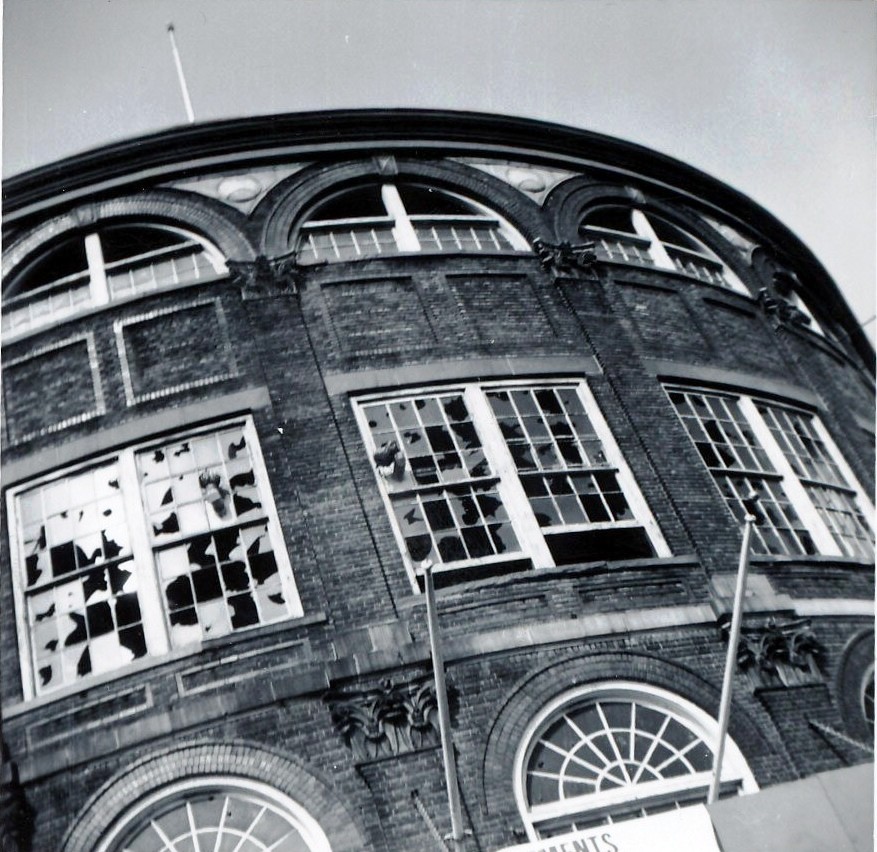

Gay Talese, a sportswriter for the New York Times before becoming a best-selling author, visited Ebbets Field after the L.A. Dodgers won the World Series in October 1959. Always a writer who pursued the offbeat, Talese filed a brief but arresting report that captured the ghostly feel of the place.38 The decay hastened after the Dodgers declined to pick up the two-year option on their lease in 1960 and the property reverted to Kratter. There is a visible difference in the number of broken windows on New Year’s Day and several weeks later.

As late as January 29, 1960, lawyer William Shea continued to dangle the possibility that Ebbets might host a team from the Continental League, albeit temporarily.39 (The permanent site in Flushing, Queens — which Robert Moses offered and Walter O’Malley rebuffed — later became Shea Stadium, home of the New York Mets.) Of course, Branch Rickey’s would-be third major league never got off the ground. It folded in August of that year. And less than a month after Shea held out that last faint hope, the wreckers descended.

Jane Leavy’s biography of Sandy Koufax referred briefly to a charity game played that final morning, when Campy, Carl Erskine, Ralph Branca, Tommy Holmes, 1913 catcher Otto Miller, and 200 fans gathered to bid their old home adieu. However, newspaper accounts don’t mention anything of the sort, and it would seem doubtful on a winter day. The closest thing may have been “Oisk” posing with the baseball-painted wrecking ball that also leveled the Polo Grounds four years later.

Relics of Ebbets Field have survived in New York City. Marvin Kratter donated 2,200 seats to the diamond that bore his name at Hart Island, the spooky prison/potter’s field site east of the Bronx in Long Island Sound. Downing Stadium on Randall’s Island in the East River got the lights. In one of several ironies, that park had been built by Robert Moses, who commanded his city makeovers from the nearby Triborough Bridge Authority headquarters. Over the years, though, nature overran Kratter Field, while the original fixtures at Downing had grown scarce by the time it was demolished in 2000.40

Yet the centerfield flagpole (also donated by Kratter Corp.) stood for more than four decades at 1405 Utica Avenue in East Flatbush. That site was a Veterans of Foreign Wars post. The most ardent Dodger supporters had hoped to transplant the pole to Borough Hall in October 2005, as part of the 50-year celebration of Brooklyn’s lone World Series championship. In another irony, that spot is just a Carl Furillo throw away from the old location of the Dodgers team offices. Sad to say, though, the former owners allegedly held out for $50,000. Lucre vs. friendly allure — Ebbets Field’s past continued to resonate.

That flagpole disappeared from view around 2007, when the Canarsie Casket Company (which succeeded the VFW) was torn down to make way for a church. Brooklyn Borough President Marty Markowitz, a big booster of Brooklyn Dodger memories, alerted Bruce Ratner, owner and developer of the Barclays Center in downtown Brooklyn, that the flagpole was available. It re-emerged in front of the arena in September 2012.41 Another irony is that Walter O’Malley had hoped to build a replacement ballpark for the Dodgers in that vicinity.

Among those attending a ceremony for the pole in December 2012 was Sharon Robinson, daughter of Dodgers hero Jackie Robinson. She said, “I think it’s a beautiful connection to Ebbets Field. . .I think he’d be very proud. . . It’s right here in the heart of the city, and that would’ve been very important to him.”42 The little jewel box has continued to enjoy a prolonged afterlife.

Soccer at Ebbets Field, 1958-59

5/25/58

Hearts of Midlothian 6, Manchester City 5

Attendance: 20,606.

Rainy and muddy. Sir Hugh Stephenson, the British Consul General in New York, handled the kickoff.

3/15/59

Halsingborg (Sweden) 2, Hakoah 2

Prelim: Ukrainian Nationals 4, Brooklyn Italians 2

Attendance: 6,500

Rainy, windy, and muddy.

5/24/59

Dundee 2, West Bromwich Albion 2

Prelim: Newark Portuguese 5, Uhrik Truckers 4

Attendance: 21,312

5/30/59

Legia (Poland) 8, Hakoah 1

Prelim: Empire State Junior Cup semi-finals

Hakoah Juniors 1, Segura 1 (2 OT)

Attendance: 5,241

6/14/59

Dundee 3, Legia (Poland) 3

Prelim: Lewis Cup

Ukrainian Nationals 2, Hakoah 1

Attendance: 12,429

6/21/59

Napoli 6, ASL All-Stars 1

Prelim: Newark Portuguese 2, Fall River SC 2

Attendance: 14,682

1,000 Napoli supporters run onto field before match to greet their club; dispersed by Babe Hamberger.

6/28/59

Two-game series for Fernet-Branca Cup

Rapid (Vienna) 1, Napoli 0

Prelim: Brooklyn Italians 2, Hakoah 2

Attendance: 18,512

Heavily pro-Napoli crowd is in bad temper. Fans spill onto field and fight in first half, causing 10-minute delay. Hundreds more riot after late goal decides game. Three officials and policeman injured.

7/1/59

Napoli 1, Rapid (Vienna) 1

Prelim: Bayside Boys Club 0, Hakoah Juniors 0

Attendance: 13,351

Extra details of city and special police keep crowd subdued in return match, though one chair is thrown from left field stands.

7/16/59

Real Madrid 6, Graz Sports Club (Austria) 2

Attendance: 13,500

P.A. announcements in Spanish, German, and English.

7/19/59

Real Madrid 8, Graz/New York Hungarians select 0

Prelim: NY Hungarians reserves 10, Austria F.C. 2

Attendance: 9,056

8/8/59

Palermo 5, ASL All-Stars 0

Attendance: 5,457

Steady downpour, muddy turf.

8/12/59

Palermo 2, Rapid Soccer Club (Vienna) 1

Prelim: Bayside Boys Club 2, Hakoah Juniors 1

Attendance: 12,598

8/16/59

Palermo 7, Italia (Toronto) 0

Prelim: Metropolitan League Cup final

Colombia S.C. (Bronx) 2, Orsogna F.C. (Astoria) 1

Attendance: 5,000

9/27/59

Hakoah 2, Newark Portuguese 1

Brooklyn Italians 5, Uhrik Truckers 2

Attendance: 1,500

10/18/59

Ukrainian Nationals 2, Brooklyn Italians 1

Hakoah 8, Elizabeth Polish Falcons 2

Attendance: not available

10/25/59

Hakoah 4, Uhrik Truckers 0

Brooklyn Italians 2, Colombo 0

Attendance: not available

Source: New York Times, American Soccer League News (Vol. 26, No. 4, November 1-8, 1959)

Author’s note

This article was originally published in The National Pastime, No. 26 (SABR: Cleveland, Ohio), 2006. This version contains updates and amendments. It has been updated and amended at various points over time, most recently on April 24, 2018.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to SABR member Alan Cohen for his input on the Hearst Sandlot Classic.

Photo Credit

Broken windows at Ebbets Field, 1960 — courtesy of Les Le Gear.

Sources

1 Joseph McCauley, Ebbets Field: Brooklyn’s Baseball Shrine (Bloomington, Indiana: AuthorHouse, 2004). Bob McGee, The Greatest Ballpark Ever (Piscataway, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2005). John G. Zinn and Paul G. Zinn, editors, Ebbets Field: Essays and Memories of Brooklyn’s Historic Ballpark, 1913-1960 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2013).

2 “‘Feeler’ Received for Ebbets Field,” The New York Times, October 17, 1957, 35.

3 Jeane Hoffman, “O’Malley Loaded with Baseball Parks,” The Los Angeles Times, May 6, 1958, C5.

4 Roscoe McGowen, “Dodgers Sublet Brooklyn Home,” The New York Times, March 5, 1958, 41.

5 “Kochman Unit Replaces Rock in N.Y. Park,” Billboard, May 19, 1958, 47. For background on the alleged riot during Allan Freed’s Big Beat show at the Boston Arena on May 3 that featured Chuck Berry and Jerry Lee Lewis, see “Rock ‘N Roll Banned in Boston After Riot That Probably Never Happened,” New England Historical Society website, May 3, 2014.

6 Telephone interview, Charlie Belknap with Rory Costello, 2005.

7 The New York Times, August 26, 1958, p. 48. The Polo Grounds was considerably more successful than Ebbets Field after its prime tenant pulled out. The National Exhibition Company (corporate name of the New York Giants) continued to focus on business at the Manhattan stadium under its lease there. Events included mammoth gatherings of Jehovah’s Witnesses, as well as long-running stock car racing and rodeo series. See Roscoe McGowen, “Polo Grounds Is Still Profitable to the Giants,” The New York Times, March 16, 1958, S1.

8 Gordon S. White Jr., “Soccer Fans Riot and Injure Three Officials and Patrolman at Ebbets Field,” The New York Times, June 29, 1959, 37.

9 William R. Conklin, “New Pro Eleven Needs Field Here,” The New York Times, August 16, 1959, S6.

10 Philip Benjamin, “Stark Acts to Force Forest Hills to Drop Bias or Cup Matches,” The New York Times, July 11, 1959, 1.

11 E-mail from Mary Lai to Rory Costello, April 10, 2006.

12 “Schreiber’s Two-Run Circuit Drive Enables St. John’s to Beat Manhattan,” The New York Times, April 25, 1958, 38. In a related curiosity, Schreiber’s final home at-bat in the majors, on 9/18/1963 (he grounded into a double play) was the last regular-season out in the Polo Grounds. However, the Latin American Players’ Game took place there on October 12.

13 Telephone interview, Ted Schreiber with Rory Costello, January 13, 2006.

14 E-mail, Al Ferrara to SABR member Paul Hirsch, March 20, 2013.

15 Morrey Rokeach, “N.Y. Hearst All-Star Team Holds Drills at Ebbetts [sic] Field,” The Sporting News, July 22, 1959, 38. “Ex-Trip Holmes NY Sandlot Head,” Binghamton (New York) Press, April 8, 1959, 50. Holmes replaced George “Snuffy” Stirnweiss, who’d died in a train wreck the previous September,

16 Al Spitzer, “Finkelberg Hits Homer A-A Snider,” Long Island Star-Journal, August 12, 1959, 20. Bearnarth went on to have an outstanding college career at St. John’s. Ott also attended St. John’s briefly but was signed by the Cubs just before the 1960 college season began. Had they been a little older, they could have been on the same team with Schreiber. Previous versions of this article incorrectly indicated that Ott was a member of the 1959 squad.

17 Al Spitzer, “US All-Stars Halt Rookies,” Long Island Star-Journal, August 15, 1959, 8. “T-U’s Moseley Impresses in Short Hill Appearance,” Albany Times-Union, August 16, 1959, E-4. “S. F.’s Fazio to Start at Short in Hearst Game,” San Francisco Examiner, August 18, 1959: III-4.

18 “Rainka, Moseley on U.S. Stars,” Albany Times-Union, July 26, 1959, B-7.

19 James L. Kilgallen, “Ex-Dodger, Giant Fans ‘Hoiting’ Real Bad,” International News Service, April 16, 1958.

20 Michael Strauss, “Van Buren Defeats Curtis for P.S.A.L. Title with Rally in Eighth,” The New York Times, June 24, 1958, 42.

21 Leo J. Callahan, “The Last Homer at Ebbets,” Elysian Fields Quarterly, Winter 2006 (this article overlooked the home run by Herm Green on August 23, 1959). Andrew Paul Mele, The Boys of Brooklyn (Bloomington, Indiana: AuthorHouse, 2008), 182, 185.

22 “Roosevelt Beats Curtis Nine by 6-5,” The New York Times, June 6, 1959, 16.

23 E-mail from Paul Jurkoic to Rory Costello, February 1, 2005.

24 Jimmy Murphy, “Duel of Strategy Between Scouts of L.A. Dodgers,” New York World-Telegram and Sun, August 22, 1959, B4. “Rookies Face Westchester Monday,” Yonkers Herald Statesman, August 8, 1959.

25 Murphy, “Duel of Strategy Between Scouts of L.A. Dodgers.”

26 “Memphis to Meet Stars’ Nine Today,” The New York Times, July 12, 1959, S4. This article noted that baseball entertainer “Prince Joe” Henry was scheduled to appear between games that day. However, Mr. Henry stated to Rory Costello (telephone interview, February 1, 2005) that he was a) out of the game in 1959, b) never appeared at Ebbets Field in his career, and c) always appeared in game action, not between games.

27 “Campy a Spectator This Time,” The Sporting News, October 15, 1958, 20.

28 “Asks ‘Campy Day’ at Ebbets Field,” Brooklyn Daily, October 6, 1958, 8. Ebbets Field stood just outside the boundaries of New York’s 12th Congressional District as they were then drawn.

29 Murphy, “Duel of Strategy Between Scouts of L.A. Dodgers.” Paul Jurkoic (e-mail to Rory Costello, April 23, 2018) was “pretty sure” that Campanella was on site, but Jurkoic did not stay for the feature game and did not remember much besides how well the field was maintained.

30 “Doubleheader at Ebbets Field,” New York Post, July 6, 1959, 43. “Negro Twin Bill Today,” The New York Times, July 26, 1959, S2.

31 “Paige Fans 4 Men and Allows 3 Hits in 3 Innings Here,” The New York Times, August 24, 1959, 25.

32 Vincent M. Mallozzi, “The Last Boys of Summer,” The New York Times, March 11, 2007.

33 “Ebbets Field Date for the Chippewas,” Yonkers Herald Statesman, September 2, 1959, 25. “Chippies Thump Haveys, 6-1; Clinch Mack Title,” Yonkers Herald Statesman, September 5, 1959, 15.

34 Brett Cyrgalis, “A Little League Game One of Last Memories from Dodgers’ Old Home,” New York Post, May 31, 2009.

35 E-mail from Lloyd Monsen to Rory Costello, March 1, 2005.

36 Telephone interview, Lloyd Monsen with Rory Costello, February 26, 2005.

37 Kilgallen, “Ex-Dodger, Giant Fans ‘Hoiting’ Real Bad”

38 Gay Talese, “Brooklyn Displays Little Enthusiasm After Dodgers Win,” The New York Times, October 9, 1959, 34.

39 Joe Reichler, “Buffalo 8th Club in Rickey League,” The Washington Post, Times Herald, January 30, 1960, 12. Shea was quoted twice floating the same idea in July 1959.

40 Daniel J. Wakin, “Ebbets Lights Dimmed Again,” The New York Times, September 27, 2000, B1.

41 Rich Calder, “Barclays honors Brooklyn history,” New York Post, September 22, 2012. At that time, Calder wrote that it was unclear whether it was the centerfield pole or another that had graced Ebbets Field. Another story speculated that it was a replica (http://atlanticyardsreport.blogspot.com/2012/09/coming-to-barclays-center-plaza.html).

42 Mike Mazzeo, “Nets hold ceremony for flagpole,” ESPN.com, December 11, 2012.