Fidel Castro and Baseball

This article was written by Peter C. Bjarkman

His fastball has long since died. He still has a few curveballs which he throws at us routinely. — Nicholas Burns, United States State Department Spokesman

Most baseball fans tend to take their idle ballpark pastimes far too seriously. On momentary reflection, even a diehard rooter would have to admit that big–league baseball’s most significant historical figures — say, Mantle, Cobb, Barry Bonds, Walter Johnson, even Babe Ruth himself — are only mere blips on the larger canvas of world events. After all, 95 percent (perhaps more) of the globe’s population has little or no interest whatsoever in what transpires on North American ballpark diamonds. Babe Ruth may well have been one of the grandest icons of American popular culture, yet little in the nature of world events would have been in the slightest degree altered if the flamboyant Babe had never escaped the rustic grounds of St. Mary’s School for Boys in Baltimore.1

Most baseball fans tend to take their idle ballpark pastimes far too seriously. On momentary reflection, even a diehard rooter would have to admit that big–league baseball’s most significant historical figures — say, Mantle, Cobb, Barry Bonds, Walter Johnson, even Babe Ruth himself — are only mere blips on the larger canvas of world events. After all, 95 percent (perhaps more) of the globe’s population has little or no interest whatsoever in what transpires on North American ballpark diamonds. Babe Ruth may well have been one of the grandest icons of American popular culture, yet little in the nature of world events would have been in the slightest degree altered if the flamboyant Babe had never escaped the rustic grounds of St. Mary’s School for Boys in Baltimore.1

Such is certainly not the case with Cuba’s most notorious pitching legend turned Communist revolutionary leader. Although Fidel Castro’s reputed blazing fastball (novelist Tim Wendel suggests in Castro’s Curveball that he lived by a tantalizing crooked pitch) never earned him a spot on a big-league roster, the amateur ex-hurler who once tested the baseball waters in a Washington Senators tryout camp nevertheless one day emerged among the past century’s most significant world leaders.2 Castro was destined to outlast nine U.S. presidents and survive five full decades of an ill-starred socialist revolution he in large part personally created. Cuba’s Maximum Leader greeted the new millennium still entrenched as one of the most beloved (in some quarters, mostly third-world) or hated (in others, mostly North American) of the world’s charismatic political figures. Certainly no other ex-ballplayer has ever stepped more dramatically from the schoolboy diamond into a role that so radically affected the lives and fortunes of so many millions throughout the Western Hemisphere and beyond.

Castro remains the most dominant self-perpetuating myth of the second half of the 20th century, and this claim is equally valid when it comes to the Cuban leader’s longtime personal association with North America’s self-proclaimed national game.3 Rare indeed is the ball fan who has not heard some version of the well-worn Castro baseball tale: that Fidel once owned a blazing fastball as a teenage prospect and was once offered big-league contracts by several eager scouts, slipshod bird dogs (especially one named Joe Cambria working for Clark Griffith’s Washington Senators) whose failures to ink the young Cuban prospect unleashed a coming half-century of Cold War political and economic intrigue.

The New York Yankees and Pittsburgh Pirates also somehow frequently make their way into the story. And in a scandalous article in the May 1989 issue of Harper’s Magazine, journalist David Truby provides perhaps the most egregious elaboration of the myth by adding the New York Giants to the list of purported Castro suitors. (Truby’s piece was actually a reprint, lifted from his monthly column in the short-lived journal Sports History.) Truby reports that Horace Stoneham was also hot on the trail of the young Castro, a “star pitcher for the Havana University baseball team,” and quotes from supposedly extant Giants scouting reports (that no one else has apparently ever seen) as his proof. Yet Truby is not alone in falling for (or in this case manufacturing) the delightful story. Reputable baseball scholars, general sports historians, numerous network news broadcasters (and even former U.S. Senator Eugene McCarthy in an obscure 1995 journal article) have been taken in by the myth of Castro as a genuine major-league pitching prospect.4

A charming related tale is also found in the June 1964 pages of Sport magazine, where ex-big-leaguer Don Hoak (aided by journalist Myron Cope) recounts a distant Havana day (reputedly during the 1950-51 winter season) when rebellious anti-Batista students interrupted Cuban League play while a young law student named Castro seized the hill and delivered several unscheduled pitches to Hoak himself. Detailed evidence deflates both the bogus Hoak rendition (easily proven to be historically impossible on several indisputable counts) and also numerous associated renditions of Castro’s pitching prowess. It turns out that Fidel the ballplayer is even more of a marvelous propaganda creation (a too-good to be scoffed at fantasy) than Fidel the lionized revolutionary hero. But this is only a small part of the fascinating and mostly — if not entirely — fictionalized Fidel Castro baseball story.

One thing is ruthlessly clear about Fidel the baseball player. The oft-presented tale of his large prowess as a potential big-league hurler simply isn’t true as normally told. It is an altogether attractive supposition — one we can hardly resist — that baseball scouts might well have changed world history by better attending to Fidel’s potent fastball. It makes perfect filler for Bob Costas during a tense World Series TV moment when Liván Hernández or “El Duque” Hernández mans the October mound. It makes tantalizing fiction in sportswriter Tim Wendel’s fast-paced novel (Castro’s Curveball, 1999), but fiction it nonetheless remains. As Bob Costas once pointedly reminded this author in personal correspondence, in this case the full-blown fiction is far too delectable ever to be voluntarily abandoned by media types who exploit its seductive appeal.5

Yet if Fidel was never a genuine pitching prospect he was nonetheless destined to emerge as an undeniable influence on baseball’s recent history within his own island nation. (And also perhaps on the big-league scene, once his 1959 revolution closed the escape hatches for numerous Cuban League stars and potential ‘60s and ‘70s-era MLB prospects like Agustín Marquetti, Antonio Muñoz, and Armando Capiró). Castro’s personal role in killing off Cuban professional baseball has been long overstated and much overhyped. (Organized baseball figures like Cincinnati GM Gabe Paul and International League President Frank Shaughnessy—plus a bevy of Washington politicos—seemingly played a far larger role than Fidel in the dismantling of the AAA league’s Havana-based Cuban Sugar Kings franchise in 1960). At the same time, the Cuban prime minister’s active involvement during the dozen or more years after seizing political power (he didn’t officially become Cuba’s president until 1976) — both in inspiring and also legislating a prosperous amateur version of the Cuban national sport — has equally been ignored by a generation and more of Stateside baseball historians.

Is Fidel Castro in the end a contemptible baseball villain (responsible for pulling the plug on the island’s pro leagues) or a certified baseball hero (architect of a nobler flag-waving rather than dollar-waving version of the bat-and-ball sport)? The answer — as with almost all elements of the Cuban Revolution — may well be a matter of one’s own personal historical and political perspectives.

It is a matter of historical record that the emergence of Castro’s at-first-socialist and later avowedly Communist revolution ended once and for all professional winter-league baseball in Cuba. But that is only a small prologue to the recent hefty Cuban baseball saga. If Castro himself is one Cuban baseball “myth” (in the negative sense of the term), it is a larger misconception still that a Golden Age of baseball ended on the island in January 1960; the larger truth is that Cuba’s baseball zenith was only reached in the second half of the 20th Century — a post-revolution and not pre-revolution era.6 Fidel Castro and his policies of amateurism were ultimately responsible during the 1960s and 1970s for rebuilding Doubleday’s and Cartwright’s sport on the island into a showcase for patriotic amateur competitions. The direct result throughout those two decades and three more to follow would be one of the world’s most fascinating baseball circuits (tense annual National Series competitions spreading throughout the entire island and leading to yearly selections of powerhouse Cuban national teams) and by far the most success-filled saga in the entire history of the world amateur and Olympic baseball movements.

If modern-era professional baseball leaves a sour aftertaste for at least some older generation North American fans fed up with out-of-control spendthrift owners and today’s gold-digging (if not steroid-enhanced) big leaguers, Cuban League action as played under Castro’s Communist government has long provided a rather attractive alternative to baseball as a capitalist free-market enterprise. In brief, the future Maximum Leader who was never enough of a fast-balling “phenom” to turn the head or open the pocketbook of scouting legend Papa Joe Cambria was nonetheless destined to play out a small part of his controversial legacy as the most significant off-the-field figure found anywhere in the sporting history of the world’s second-ranking Western Hemisphere baseball power.

The Hoak Hoax

Don Hoak didn’t exactly create the myth of Fidel Castro the baseball pitcher. Nonetheless the light-hitting infielder did contribute rather mightily to the spread of one of balldom’s most elaborate historical hoaxes. The journeyman career of the former Dodgers, Cubs, Reds, Pirates, and Phillies third baseman is in fact almost solely renowned for two disastrous wild tosses — one on the diamond and the other in the interview room. In the first instance, Hoak unleashed the wild peg from third base on May 26, 1959, that sabotaged teammate Harvey Haddix’s 12 innings of pitching perfection in Milwaukee’s County Stadium (and in the process baseball’s longest big-league perfect game). In the latter case, he teamed with a notoriety-seeking sportswriter to spin an elaborate false yarn about facing the future Cuban revolutionary leader in a highly improbable batter-versus-hurler confrontation laced with romance and dripping with patriotic fervor.

The fabricated story of Hoak’s memorable square-off against one of the most famous political leaders of the 20th century did little to immortalize the ex-big-leaguer himself. Yet it was destined to become yet another piece of the circulating printed and oral record that worked overtime to establish Fidel Castro’s own seemingly-impressive baseball credentials.

Hoak conspired with journalist Myron Cope and the editors of Sport magazine to craft his fictionalized tale in June 1964 (only weeks after his career-ending release by the Philadelphia Phillies), thus launching one of the most widely swallowed baseball hoaxes of the modern era. As Hoak tells the story, his unlikely and unscheduled at-bat against young Castro came during his own single season of Cuban winter league play, which the ex-big-leaguer conveniently misremembers as the offseason of 1950-51. Hoak’s account involves a Cuban League game between his own Cienfuegos ball club and the Marianao team featuring legendary Havana outfielder Pedro Formental. The convenient backdrop was political unrest surrounding the increasingly unpopular government of military strongman Fulgencio Batista. During the fifth inning and with American Hoak occupying the batter’s box, a spontaneous anti-Batista student demonstration suddenly broke out (Hoak reported such uprisings as all-too-regular occurrences during that particular 1951 season) with horns blaring, firecrackers exploding, and anti-Batista forces streaming directly onto the field of play.

Hoak’s account continues with the student leader — the charismatic Castro — marching to the mound, seizing the ball from an unresisting Marianao pitcher, and tossing several warm-up heaves to catcher Mike Guerra (a Washington Senators big-league veteran). Castro then barks orders for Hoak to assume his batting stance, the famed Cuban umpire Amado Maestri shrugs agreement, the American fouls off several wild but hard fastballs, the batter and umpire suddenly tire of the charade, and the bold Maestri finally orders the military police (“who were lazily enjoying the fun from the grandstand”) to brandish their riot clubs and drive the student rabble from the field. Castro left the scene “like an impudent boy who has been cuffed by the teacher and sent to stand in the corner.”7

Hoak’s wild tale underpinned a myth that was soon to take on a ballooning life of its own. The Hoak-narrated details are perhaps charming but highly suspect from the opening sentence. Misspellings and misapprehensions of names, plus confusion of the baseball details, immediately destroy any credibility the account might carry. The star Cuban outfielder is Formental (not “Formanthael” as Hoak and Cope have it spelled) and Formental was actually a Club Havana outfielder and not a member of the Marianao team during the early ‘50s (he had played for Cienfuegos a decade earlier, before being traded to Havana for Gil Torres in the mid-‘40s); the umpire is Maestri (not Cope’s spelling of “Miastri”); backstop Fermín (as he was always known in Cuba) Guerra would have been managing the Almendares team at the time and not catching for the ball club playing under the banner of Marianao.

To add to the implausibility of the account, the reported events themselves are entirely out of character with the several personalities allegedly involved, especially those details concerning umpire Maestri. Amado Maestri was reputed the island’s best mid-century arbiter, a bastion of respectability, and a man who had once even ejected Mexican League mogul Jorge Pasquel from the stadium grounds in Mexico City. This was not a spineless umpire who would have tamely ceded control of the playing field for even a split instant to troublemaking grandstand refugees of any known ilk — especially to rabble-rousing anti-government forces. In short, the details are so scrambled and outrageously inaccurate as to suggest that Hoak (and literary assistant Cope) had indeed related this tale with tongue firmly planted in cheek, and also with a clear aim of tipping off any informed reader as to the elaborate literary joke.

Amateur baseball historian and Cuban native Everardo Santamarina has already pointed out (in SABR’s The National Pastime, Volume 14, 1994) the rampant inconsistencies and overall illegitimacy of the farfetched Hoak account. Santamarina does so largely by stressing the contradictions related to Hoak’s own winter league career (botched dates, incorrect Cuban ballplayer names, inaccurate portrayal of umpire Maestri). Santamarina is right on target by again emphasizing the total implausibility of the umpire’s role in the tale. And Santamarina astutely concludes that “not even Babe Ruth’s ‘Called Shot’ ever got such a free ride.”8

There are also available facts from the Fidel Castro side of the ledger (facts largely unnoted by Santamarina) that are just as persuasive in putting the lie to Hoak’s fabricated account. An even loser playing with the historical details than with the baseball data is apparent to any reader even vaguely familiar with legitimate accounts of the Cuban Revolution. For starters, Pedro Formental was a well-known Batista supporter and thus not likely “a great pal of Castro” and Fidel’s “daily companion at the ballpark” as Hoak reports. While Fidel had in truth just received his University of Havana law degree in 1950 as Hoak accurately announces, Batista for his part was not then in power (he only reassumed the presidency via a coup d’état in March 1952); the student movement against Batista led by Castro was thus still several years away. Still more damaging is the fact that Hoak himself was not even in Cuba the year he claims, nor did he ever play for the team he cites before the winter season of 1953-54, on the eve of his rookie big-league season in Brooklyn. By the time Hoak did make his way onto the Cienfuegos roster, Castro was no longer in Havana but rather spending time in jail on the Isle of Pines, serving a two-year lock-up for his part in the Moncada Rebellion of July 1953, an incarceration from which he was not released until May (Mother’s Day) 1955.

It might be noted here that there was in truth an actual event somewhat similar to the one Hoak fictionalizes, and this occurrence may indeed have contained the fertile seeds for the story conveniently dreamed up with ghostwriter Myron Cope. Cuban students did in fact interrupt a ballgame in Havana’s El Cerro Stadium (also called Gran Stadium at the time) in early-winter 1955, leading to a swift intervention by Batista’s militia and not by the game’s beleaguered umpire. Castro at the time was already released from prison, but was now safely ensconced in Mexico City.

But in this case, as in most others, historical facts rarely stand in the way of enticingly good baseball folklore. The Hoak-Cope tale soon gained superficial legitimacy with its frequent revivals. Journalist Charles Einstein placed his own stamp of authority with an unquestioning and unaltered reprint in The Third Fireside Book of Baseball (1968), and then again in his Fireside Baseball Reader (1984). Noted baseball historian John Thorn follows suit in The Armchair Book of Baseball (1985), adding a clever legitimizing header above the story which reads: “Incredible but true. And how history might have altered if Fidel had gone on to become a New York Yanqui, or a Washington Senator, or even a Cincinnati Red.” A Tom Jozwik review of the Thorn anthology (SABR Review of Books, 1986) stresses with naïve amazement that the subject of the “autobiographical” piece is indeed Cuba’s Fidel Castro and not major league washout Bill Castro.9

The Prospect Myth

Hoak’s entertaining if bogus fantasy is admittedly full of foreshadowing, even if it is genuinely flimsy and fabricated. While neither Castro nor Hoak were simultaneously in Havana at the time the future political leader reputedly challenged the future big-league hitter (Hoak wasn’t there in 1951 and Castro wasn’t there in 1954), what is most remarkable about the clearly apocryphal tale is the degree to which its all-too-easy acceptance over the years parallels dozens of other similar accounts concerning Fidel as a serious mound star — even a talented pitching prospect of big-league proportions. Legions of fans have down through the years run across the Fidel Castro baseball legend in one or another of its many familiar formats.

The story usually paints Fidel as a promising pitching talent who was scouted in the late ‘40s or early ‘50s (details are always sketchy) and nearly signed by a number of big-league clubs. The widely circulated version is the one that involves famed Clark Griffith “bird-dog” Joe Cambria and the Washington Senators. But the New York Giants, New York Yankees, and Pittsburgh Pirates (as already noted) often get at least a passing mention. It is just too grand a story and thus has been swallowed hook, line, and fastball. If only scouts had been more persistent — or if only Fidel’s fastball had a wee bit more pop and his curveball a bit more bend — the entire history of Western Hemisphere politics over the past half-century would likely have been drastically reshaped. Kevin Kerrane quotes Phillies Latin America scouting supervisor Ruben Amaro (a Mexican-raised ex-big leaguer whose own father was Cuban League legend Santos Amaro) on this familiar theme. Amaro (repeating that Cambria twice rejected Castro for a contract) deduces that “Cambria could have changed history if he remembered that some pitchers mature late.”10 It is a fantasy devoutly to be wished and thus quite irresistible in the telling.

Even highly reputable baseball scholars, general sports historians, and experienced network news broadcasters have often been taken in by the charming tale. Kevin Kerrane (as noted) reports the Castro tryout story in his landmark book on scouting (Dollar Sign on the Muscle, 1984) by observing (somewhat accurately if incompletely) that “at tryout camps Cambria twice rejected a young pitcher named Fidel Castro.” Others have done the same and often with considerably less restraint. Michael and Mary Oleksak (Béisbol: Latin Americans and the Grand Old Game, 1991) quote both Clark Griffith and Ruben Amaro on the legend of Fidel and Papa Joe without much helpful detail but with the implication that it is more fact than fiction. John Thorn and John Holway (The Pitcher, 1987) pursue a more cautious route in citing Tampa-based Cuban baseball historian Jorge Figueredo’s rebuttal that “there is no truth to the oft-repeated story.”

The most unrestrained recounting of the myth occurs in Truby’s Harper’s reprint. Author Truby repeats the well-worn line that a Castro signing might have truly changed history. He also reports that Horace Stoneham had his New York Giants hot on the trail of young Castro, who was “a star pitcher for the University of Havana baseball team,” and even quotes scouting reports from Pittsburgh’s Howie Haak (“a good prospect because he could throw and think at the same time”), Giants Caribbean scout Alex Pompez (“throws a good ball, not always hard, but smart … he has good control and should be considered seriously”), and Cambria (“his fastball is not great but passable … he uses good curve variety … he also uses his head and can win that way for us, too”). The trouble here (and it is considerable trouble indeed) is that no other known source ever reports on such existing or once-available scouting reports. (It might also be noted that the lines quoted hardly sound like serious assessments from legitimate scouts — seasoned talent hounds far more likely to report radar gun readings, or in the 1950s perhaps more impressionistic yet still more plausible measures of arm speed — than impressions of quick-wittedness.)

All additional commentary (especially that coming from Castro’s many biographers and from within Cuba itself) indicates that as a schoolboy pitcher Fidel threw hard but wildly (the exact opposite of Truby’s quotes). And Castro in reality never made the University of Havana team (let alone being the team’s star performer); his schoolboy baseball playing was restricted to 1945, as a high school senior. Truby caps his account with a report (supposedly from Stoneham’s lips) that Pompez was authorized to offer a $5,000 bonus for signing (a ridiculous figure in itself, since no Latin prospects were offered that kind of cash in 1950, most especially one who would have been 23 or 24 at the time) which Castro stunned Giants officials by rejecting. The biggest curveball in the Harper’s account is quite obviously the one being tossed at readers by author David Truby himself.

With the past half-century explosion of interest in Latin American ball-playing talent (and thus also in the history of the game as it is played in Caribbean nations), the Castro baseball legend has inevitably taken on a commercial tone as well. One producer of replica Caribbean league hats and jerseys has recounted the glories of Fidel the pitcher (in its catalogs and on its website) and manages in the process to expand the story by trumpeting Fidel as a regular pitcher in the Cuban winter leagues. By the early 2000s, The Blue Marlin Corporation website was reporting that their promotional photo of Castro was actually a portrait of the dictator pitching for his famed military team (“The Barbudos”) in the Cuban League, whereas in reality the exhibition outing was nothing more than a staged one-time affair preceding a Havana Sugar Kings International League game. ESPN had a decade earlier already produced a handsome promotional flyer that used Fidel’s baseball “history” as part of the hook to sell its own televised games. The 1994 ESPN poster promoting Sunday night and Wednesday night telecasts featured the same familiar 1959 photo of Fidel delivering a pitch in his Barbudos uniform, here superimposed with the bold-print headline “The All-American Game That Once Recruited Fidel Castro.”

One of the more interesting promotions of the Fidel ballplayer myth comes with a Eugene McCarthy essay distributed in the journal Elysian Fields Quarterly (Volume 14:2, 1995) and reprinted from an earlier editorial column in USA Today (March 14, 1994). Here the ex-senator and former presidential candidate stumps (half-seriously one presumes) for Fidel as the much-needed big-league baseball commissioner (“what baseball most needs — an experienced dictator”). While McCarthy may deliver his proposals tongue-in-cheek when it comes to the commissioner campaign, he nonetheless apparently buys into the myth of Fidel’s ball-playing background. Thus: “Another prospect eyed by the Senators was a pitcher named Fidel Castro, who was rejected because scouts reported he didn’t have a major-league fastball.” Equally sold were EFQ editors, who commissioned artist Andy Nelson to create a volume-cover fantasy 1953 Topps baseball card of a bearded Castro in Washington uniform as pitcher for the Clark Griffith-era Washington Senators.

Andy Nelson’s fantasy Topps 1953 bubble gum card inevitably features some immediate signals of historical anachronism for perceptive or wary readers. A 1953 Topps card neatly fits the artist’s purpose, since in that particular year the Topps Chewing Gum Company indeed used just such artists’ drawings of ballplayers (mostly consisting of head portraits only) and Nelson’s pen-and-ink portrait thus has a special feeling of reality about it. But of course Castro in early-season 1953 was still a non-bearded student about to launch his revolutionary career (not his ball-playing one) with an ill-fated attack on the Moncada military barracks in Santiago.

Despite all this media promotion, the entire Castro pitching legend is in the end just as much unsubstantial myth as was Hoak’s published account of facing the revolutionary hurler back in 1951 (or 1954, or whatever season it might have been). Fidel was never a serious pitching prospect who might demand a $5,000 bonus or even a serious contract offer. He was never pursued by big-league scouts or specifically by Joe Cambria. (Recall here that Cambria’s modus operandi was to sign up every kid in Cuba with even passing promise and then let the Washington spring training camp sort them out later; if Fidel Castro had any legitimate big-league talent, Cambria could hardly have missed him.) Fidel was never on his way to the big leagues in Washington or New York or any points between, no matter how intriguing might be the circulating story that (but for a trick of cruel fate or a misjudgment by Papa Joe) he could have been serving up smoking fastballs against ‘50s-era Washington American League opponents, instead of launching political curveballs against ‘60s-era Washington bureaucrats.

What then are the true facts surrounding Fidel Castro and baseball, especially those touching on Fidel’s own ball-playing endeavors? Close examination of the historical and biographical records makes a number of points indisputably clear. First, the young Fidel did indeed have a passion for the popular sport of baseball, one that was apparent in his earliest years in Cuba’s eastern province of Oriente. Biographer Robert Quirk (Fidel Castro, 1993) reports on the youngster’s apparent fascination with the Cuban national game, and especially his attraction to its central position of pitcher (“the man always in control”). But it is also obvious from widely available biographical accounts that young Fidel was mostly enamored of his own abilities to dominate in the sporting arena (as in all other schoolboy arenas) and not with the lure of the game itself. He organized an informal team as a youngster in his hometown of Birán when his wealthy landowner father provided the needed supplies of bats, balls and gloves (Szulc, Fidel: A Critical Portrait, 1986). And when he and his team didn’t win games, he simply packed up his father’s equipment and trudged home. Fidel from the start apparently was never a team player or much of a true sportsman at heart.

Fidel’s baseball fantasies were (like those of so many of us) never to be matched by any remarkable batting or throwing talent. As a high school student, Fidel maintained his early passion for sports and played on the basketball team at Belén, the private Havana Catholic secondary school he attended during the years 1942-1945. He also pitched on the baseball squad as a senior, as well as being a star at track and field (middle distances and high jumping) performer and also a Ping Pong champion.

Later efforts of Castro’s inner circle (though seemingly never of Fidel himself) to promote his well-rounded image by fanning the rumors of athletic prowess are already apparent in connection with schoolboy days. Biographer Quirk (whose exhaustive study is the most recent and one of the most scholarly in a long list of Fidel biographies published in both Spanish and English) reports on uncovering numerous unsubstantiated accounts that Fidel was selected Havana’s schoolboy athlete of the year for 1945. Yet when Quirk tirelessly pored over every single daily issue of the Havana sports pages (in Diario de la Marina) for that particular year he could find not a single mention of Castro’s name. In a footnote to his account Quirk ironically demonstrates his own carelessness of historical details when he notes that the actual outstanding schoolboy star of that 1945 season was reported by Diario to be Conrado Marrero, an amateur pitching hero who himself became legendary on Cuban diamonds of the late ‘40s and early ‘50s and who actually did make it onto the Washington Senators major-league roster. What Quirk overlooks is the fact that Marrero was already 34 in 1945 and had long been established as a top star on the Cuban amateur national team since the late ‘30s.

Yet there does turn out to be a source after all in the Belén high school years for the essence of the Castro baseball legend. Biographer Quirk falsely assumed Fidel’s recognition as a top schoolboy athlete to be based on his senior season, when in actuality the recognition came a year earlier in 1943-44. Another Fidel chronicler, Peter G. Bourne (Fidel, 1988), does indeed acknowledge Castro’s status as a top basketball player at Belén, and also his recognition as Havana’s top schoolboy sportsman during that earlier winter. Bourne also emphasizes Fidel’s penchant for using athletics (as he also used academics, the debate society, and student politics) as a convenient method for proving he could excel in almost any endeavor imaginable. Fidel was so driven in this way that he once wagered a school chum he could ride his bicycle full speed into a brick wall. He succeeded, but the attempt actually landed him in the school infirmary for several weeks.

It is the Belén athletic successes that in the end contain the hidden key to the legend of Fidel the baseball prospect. By the mid-‘40s Joe Cambria had been for some time running his Washington Senators scouting activities from a Havana hotel room (also his part-time residence) and also holding regular open tryout camps for the legions of eager Havana prospects, as well as beating the bushes around the rest of the island to seek out cheap Cuban talent. Fidel is reported (by Bourne) to have showed up uninvited at two of these camps between his junior and senior years, largely to prove to school chums that he might indeed be good enough to earn a pro contract offer. Castro, in other words, sought out Cambria and the pro scouts and not vice versa.

Nonetheless, no contract was ever offered to the hard-but-wild- throwing prospect. And as biographer Bourne stresses, any offer would almost certainly have been rejected in any case. Fidel was a privileged youth from a wealthy family and thus had other prospects looming on the horizon (a lucrative career in law and politics) far more promising than pro baseball. Ball-playing as an occupation would actually have been a step down for any prospective law student of that decade. There were no big bonus deals in the 1940s, especially in Cuba where Cambria’s mission for the penny-pinching Clark Griffith was to find dirt-cheap talent among lower-class athletes desperate to sign for next-to-nothing. Fidel’s own promising future was already assured in the lucrative fields of law and politics. His reported fascination with baseball could never have been more than the compulsive showoff’s momentary diversion — an endeavor devoid of captivating dreams of escape into big-league glories or elusive promises of big-league riches.

When he next put in his time as a student at the University of Havana, Fidel’s ball-playing fantasies were apparently not yet entirely squelched and he did play freshman basketball and also try out — although unsuccessfully — for the college varsity baseball team. But as biographer Quirk notes, ballplayers in Cuba (as well as top athletes in other sports) were already by the late ‘40s coming mostly from poorer African descendants among the populace, not from the upper crust of privileged students like Fidel. The future politician displayed an abiding fascination for ball-playing (especially basketball and soccer, as later interviews would reveal) that would remain with him in future years. But it was unquestionably evident even to Fidel during college days that he had little serious talent as a baseball hurler. Furthermore, political activities preoccupied the ambitious law student from 1948 onward and left almost no available time for any serious practice on the baseball field. While his numerous biographers cover every aspect of his life in painstaking detail, none mention any further tryouts for baseball scouts, any serious playing on organized teams, indeed any baseball activity at all until his eventual renewed passion for the game as a dedicated fan. And the latter came only after the successful rise to political power in January 1959. Quirk and Bourne alone among Castro biographers emphasize Fidel’s ball-playing, and then only to report that baseball never quite measured up to basketball or track and field as an arena for displaying athletic skill or for releasing an obsessive drive for unlimited personal success.

When he next put in his time as a student at the University of Havana, Fidel’s ball-playing fantasies were apparently not yet entirely squelched and he did play freshman basketball and also try out — although unsuccessfully — for the college varsity baseball team. But as biographer Quirk notes, ballplayers in Cuba (as well as top athletes in other sports) were already by the late ‘40s coming mostly from poorer African descendants among the populace, not from the upper crust of privileged students like Fidel. The future politician displayed an abiding fascination for ball-playing (especially basketball and soccer, as later interviews would reveal) that would remain with him in future years. But it was unquestionably evident even to Fidel during college days that he had little serious talent as a baseball hurler. Furthermore, political activities preoccupied the ambitious law student from 1948 onward and left almost no available time for any serious practice on the baseball field. While his numerous biographers cover every aspect of his life in painstaking detail, none mention any further tryouts for baseball scouts, any serious playing on organized teams, indeed any baseball activity at all until his eventual renewed passion for the game as a dedicated fan. And the latter came only after the successful rise to political power in January 1959. Quirk and Bourne alone among Castro biographers emphasize Fidel’s ball-playing, and then only to report that baseball never quite measured up to basketball or track and field as an arena for displaying athletic skill or for releasing an obsessive drive for unlimited personal success.

Fidel’s most notable chronicler (Tad Szulc) does, however, mention one later event that sheds considerable light on Castro’s sublimated athletic interests. Szulc reports an interview in which Fidel suddenly and unexpectedly began to expound on the important symbolic values of his favored schoolboy sport, basketball. Basketball, Fidel would observe, could provide valuable indirect training for revolutionary activity. It was a game requiring strategic and tactical planning and overall cunning, plus speed and agility, the true elements of guerrilla warfare. Baseball, Fidel further noted, held no such promise for a future revolutionary. Most significantly, Szulc points out that Fidel’s comments on this occasion came during a candid response in which he “emphatically denied” the reported rumors that he once envisioned a career for himself as a professional pitcher in the North American major leagues.

The Barbudos Exhibition

The true impetus for tales and legends of Fidel as serious ballplayer seems to follow as much from the Maximum Leader’s post-revolution associations with the game as from any bloated reports concerning his imagined role as an erstwhile schoolboy prospect. Central here are oft-recounted (but rarely accurately portrayed) exhibition-game appearances at stadiums in Havana and elsewhere across the island during the first decade following the 1959-1960 Communist takeover. The most renowned single event, of course, was Fidel’s onetime appearance on the mound in El Cerro Stadium (home of the Havana/Cuban Sugar Kings) wearing the uniform of his own pickup nine, aptly christened “Los Barbudos” (“The Bearded Ones”). Rarely, however, have any stateside baseball historians or the North American press ever gotten the well-traveled “Barbudos” story entirely straight.

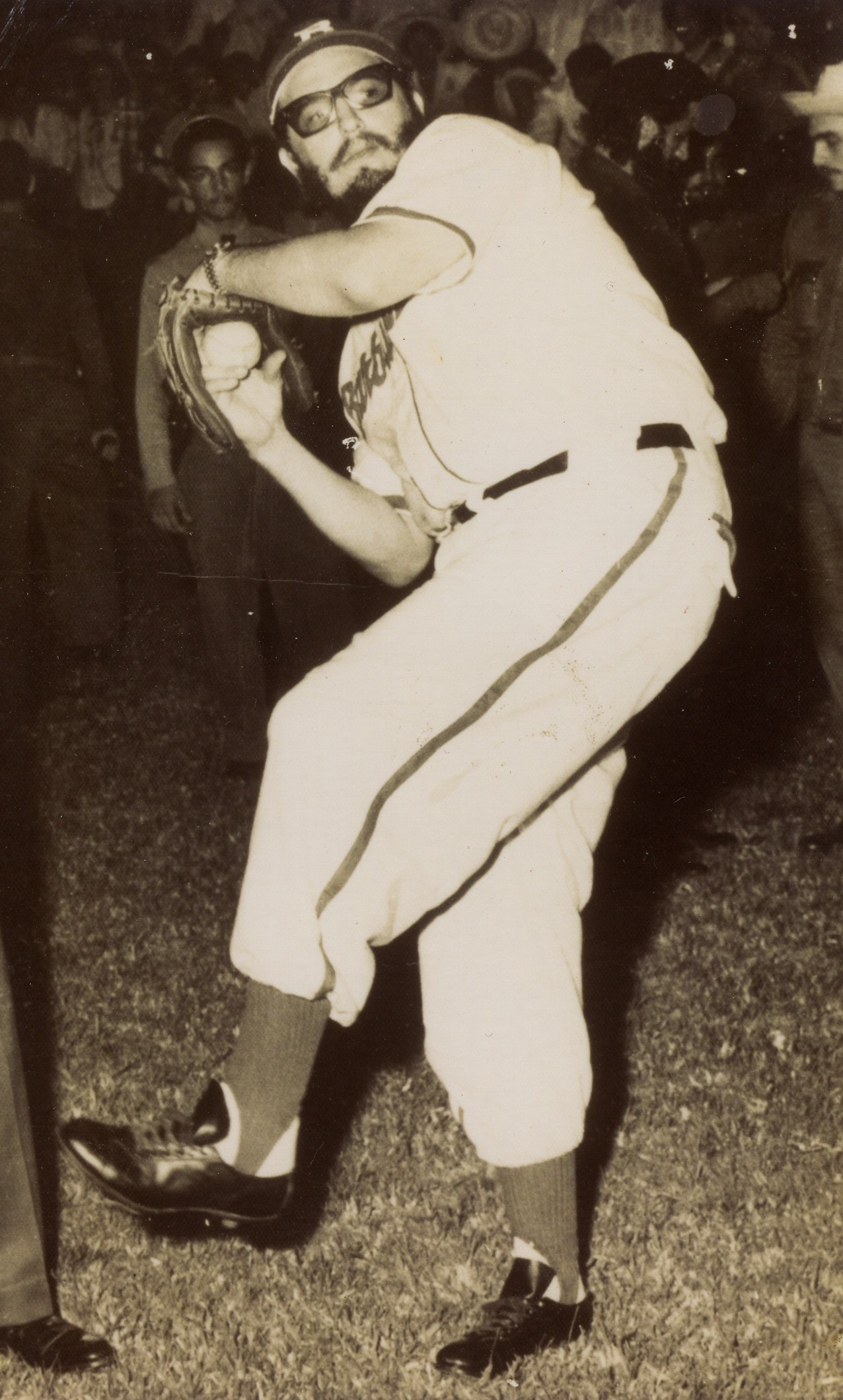

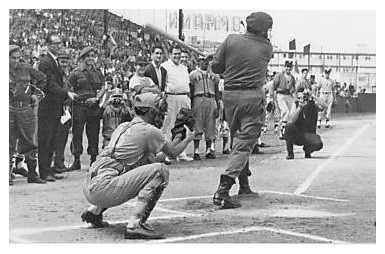

The celebrated but little-understood Barbudos game took place in Havana on July 24, 1959, before a crowd of 25,000 “fanáticos” (26,532 to be precise), as a preliminary contest to a scheduled International League clash between the Rochester Red Wings and Havana Sugar Kings. A single pithy newspaper account from the Rochester (New York) Democrat and Chronicle provides the source for most details of the evening’s events and also for a familiar Castro action photo that later accompanied most “Castro-as-phenom” pitching tales.

Fidel is reported (by Democrat and Chronicle writer George Beahon) to have practiced all day in his hotel room for his two-inning stint with the Cuban Army pick-up team which faced a squad of military police. (He is also reported in Beahon’s account to have been a onetime high-school pitcher and to have “tried out” for the college team, but no mention is made of any collegiate competition or of any interest among scouts in his moderate throwing talents.)11 Castro pitched both pre-game exhibition innings and was captured on the mound (and at-bat) in the several action photos (he wore number 19) that would later become the only widely seen images of Cuba’s Maximum Leader turned baseball pitcher. The entire latter-day public impression of Fidel as talented moundsman (in the U.S. at least) is indeed built largely if not exclusively upon the existing photographic images culled from this single evening’s events.

Fidel struck out two members of the opposing military team (one with the aid of a friendly umpire, on a call that had Fidel dashing toward the batter’s box to shake hands with the overly cooperative arbiter). He is reported to have “needlessly but admirably” covered first on an infield grounder, to have bounced to short in his only turn at bat (captured by a photo in the next afternoon’s Havana daily), and to have demonstrated surprisingly good mound style — “wild but fast, and with good motions.” But the most memorable moment of the evening was reserved for still another military hero of the revolution, Major Camilo Cienfuegos, who was originally scheduled to hurl for the opposing MP team. “I never oppose Fidel in anything, including baseball,” announced the astute Cienfuegos, who then donned catcher’s gear and went behind the plate for Fidel’s Barbudos army squad.

If Major Cienfuegos would not risk upstaging Comandante Castro, the activities of lesser-known henchmen soon enough would. A single evening later came one of the most infamous and portentous events of Cuban baseball history — the oft-reported shooting incident in which Rochester third-base coach Frank Verdi and Havana shortstop Leo Cárdenas were apparently nicked by stray bullets launched by revolutionary zealots who had crowded into El Cerro Stadium to celebrate the first Cuban Independence Day since Castro’s rise to power.

The volatile occasion for mixing baseball with revelry was the first and much anticipated “July 26th Celebration” of the revolutionary era, and baseball and local politics were thus about to collide head-on. Fulgencio Batista had fled the island on January 1, 1959, allowing Castro-led rebels to seize effective control of the entire country. The July 26 date commemorated a 1953 failed attack by 125 Castro-led student rebels against the Moncada army barracks in Santiago, an event that subsequently lent its name to the entire Castro-inspired revolutionary movement. (Fidel’s rebel army was itself officially known as the July 26 Brigade.) The events of the moment had been further spiced by Fidel’s dramatic resignation as prime minister only nine days earlier in a power struggle with soon-to-be-ousted President Manuel Urrutia; Fidel reassumed the top government post at the conclusion of this very weekend’s dramatic patriotic celebrations.

What followed that night in El Cerro Stadium was as much a comedy of errors as it was a tragedy of misunderstanding. And once more the facts surrounding the shooting incident itself, and the stadium frenzy that both preceded and followed, rarely get told correctly.

Beleaguered Rochester Red Wings manager Ellis “Cot” Deal three decades later painstakingly recounted the memorable events in his self-published autobiography (Fifty Years in Baseball — or, “Cot” in the Act, 1992), a rare first-hand version subsequently verified in interviews with the present author. In a stadium jammed-packed with guajiros (peasants from the Cuban countryside) and barbudos (Castro’s soldiers, who like his military team of the previous evening, drew their moniker from the thick beards worn by most) — all on hand for a planned midnight “July 26” celebration — the two International League teams initially finished a suspended game, then waded through the explosive atmosphere and intense tropical heat to a 3-3 tie at the end of regulation innings in the regularly-scheduled affair. The preliminary contest was the completion of a scoreless seven-inning game from the Red Wings’ previous trip into town a month earlier.

Manager Deal suspected early on that the night would be long and eventful, especially when the umps and rival skippers (Deal and Sugar Kings boss Preston Gómez) met at the plate to discuss (in lieu of customary ground rules) what would transpire in the highly likely case of serious fan interference. Havana scored in the bottom of the eighth to win the preliminary and thus the festive stadium mood was further enlivened.

Veteran big-leaguer Bob Keegan had mopped up the preliminary game (since he had also been the starter of the suspended game in June) and was once more on tap by accident of the pitching rotation to start the regularly scheduled affair to follow. Keegan pitched courageously despite the oppressive heat and held a 3-1 lead into the bottom of the eighth when sweltering humidity finally sapped his energy and Deal resignedly changed hurlers. Tom Hurd closed the door in the eighth, but a walk and a homer by Cuban slugger Borrego Alvarez in the bottom of the ninth spelled dreaded extra innings.

Next to unfold was the dramatic patriotic interruption. With the crowd — an overflow throng which topped 35,000 — now at fever pitch, the regulation game was halted at the stroke of midnight; stadium lights were quickly extinguished, press box spotlights focused on a giant Cuban flag in center field and the Cuban anthem was played slowly and reverently. As soon as stadium lighting was rekindled, however, all hell broke loose and the air was suddenly filled with spasms of celebratory gunfire launched from both inside and outside the ballpark. A close Havana friend of the author, in attendance that night, would recently recounts how a patron seated next to him near the visiting team dugout emptied several rounds from his pistol directly into the on-deck circle. Deal also vividly recalls one overzealous Cuban soldier (perhaps the selfsame individual) unloading an automatic pistol into the ground directly in front of the Red Wings dugout.

Play resumed with further sporadic gunfire occasionally punctuating the diamond actions. Infielder Billy Harrell homered in the top of the 11th to give Rochester the momentary lead, but in the bottom of the frame the home club rallied and the crowd thus again reached new heights of delirium. When Sugar Kings catcher Jesse Gonder (an American) led off the bottom of the frame with a hit slapped down the left-field line and raced toward second, he seemed (at least to skipper Deal) to skip over the first-base sack while rounding the bag, an event unnoticed by the rooting throng but one that predictably sent manager Deal racing on-field to argue with umpires stationed at both first and home.

Naturally fearing an imminent riot if they now called anything controversial against the rallying home club, neither of the arbiters was disposed toward hearing Deal’s protests, which under calmer circumstances might have seemed valid. (Deal thought that first base ump Frank Guzetta had turned too quickly to follow the runner to second, in case a play was made there, and therefore missed Gonder’s sidestepping of first; he merely wanted the home plate ump to help out on the play.) Guzetta ignored Deal’s pleas and moments later the Rochester skipper was ejected for continuing his vehement protests. Gonder soon scored the lone run of the inning and the contest continued into the 12th once more knotted, now at four apiece. Having already been banished to the clubhouse, Deal himself would not be on hand to witness firsthand the further drama that next unfolded.

In the moments that followed, Deal’s ejection ironically proved to be a significant event. As a chagrined Deal later recounted the circumstances of that “heave-ho” from the field of play, he had to admit that umpire Frank Guzetta had reacted more out of deep wisdom than out of shallow self-defense. In the heat of the argument Deal had grabbed his own throat, giving a universal “choke” sign that led instantaneously to another universally understood gesture — the “thumb” which is Spanish for “adios” and English for “take a shower.” Deal in hindsight would be much more sympathetic to the umps’ plight and would realize that any attempt to reverse the decision on Gonder’s base running might well have further ignited an already rowdy (and heavily-armed) grandstand throng with quite disastrous consequences.

Back on the field, fate and happenstance were once more about to intervene. More random shots were fired as play opened in the 12th, and stray bullets simultaneously grazed both third-base coach Frank Verdi and Sugar Kings shortstop Leo Cárdenas. By now the frightened umps and ballplayers had seen enough. The game was immediately suspended by the umpires as Verdi, still dazed, was hastily carried by ashen teammates toward the Rochester locker room, followed closely by a wild swarm of escaping ballplayers. Apparently a falling spent shell had struck Verdi’s cap (which fortuitously contained a protective batting liner) and merely stunned him. Deal (oblivious to on-field events) had just stepped from the shower when his panic-stricken team burst into the clubhouse carrying the barely conscious Frank Verdi. The runway outside the Red Wings dressing room was pure chaos as the umpires and ballplayers from both clubs scrambled for safety within the bowels of the ballpark. An immediately apparent irony was the fact that the wounded Verdi had that very inning substituted for the ejected manager Deal in the third-base coach’s box, and while Verdi always wore a plastic liner in his cap, the fortune-blessed Deal never used such a protective device. Thus Deal’s ejection from the field had likely saved the fate-blessed manager’s life, or at the very least prevented notable injury.

While umpires next desperately tried to phone league president Frank Shaughnessy back in New York for a ruling on the chaotic situation, manager Deal and his general manager, George Sisler Jr., had already decided on their own immediate course of action. It was to get their team safely back to the downtown Hotel Nacional and then swiftly onto the next available plane routed for Rochester (or at least Miami). But some Cuban fans in attendance at the packed El Cerro Stadium that night (a few have been interviewed over the years by the author in Havana) today hold very different memories of the event, perhaps colored by the changing perspective or fading recollections of several passing decades. They remember few shots, little that was hostile in the crowd’s festive response to both the patriotic celebration and the exciting ballgame, and hardly any sense of danger to either the ballplayers or the celebrants themselves. And Cuban baseball officials at the time also had a slightly different interpretation, vociferously denying that the situation was ever truly out of control and pressing the Rochester manager and general manager to continue both the suspended match and the regularly scheduled game on tap for the following afternoon.

Captain Felipe Guerra Matos, newly appointed director of the Cuban sports ministry, one week later cabled Rochester team officials with a formal and truly heart-felt apology, assuring Red Wings brass that Havana was entirely safe for baseball and that their team (and all other International League ball clubs) would be guaranteed the utmost security on all future trips to the island. Guerra Matos saw the events of the evening only as a spontaneous outpouring of unbridled nationalistic joy and revolutionary fervor by emotional Cuban soldiers and enthusiastic if unruly peasants, and thus a celebration of freedom no more unseemly perhaps than many stateside Fourth of July celebrations.

But Deal and Sisler at the time persisted, despite the pressures and threats of Cuban officials which continued throughout the night and subsequent morning. After a tense and seemingly endless Sunday, sequestered at the seaside Hotel Nacional amidst the revolutionary revels continuing in the streets around them, the Rochester ball club was finally able to obtain safe passage from José Martí Airport before yet another nightfall had arrived.

Deal decades later (his book was published in 1992 and my own interview with him occurred in 2004) penned an entertaining account of the labored efforts of Cuban officials to get his team to complete the weekend series, including the previous night’s suspended match as well as the scheduled Sunday afternoon affair. While a World War II vintage bomber strafed an abandoned barge in Havana harbor as part of the ongoing revolutionary revelries, Deal and his general manager met with a pair of Cuban government officials in Sisler’s hotel room, fortified only by strong cups of black Cuban coffee. The Cuban government spokesmen — in Deal’s account — pleaded, cajoled, and then finally even threatened boisterously in their efforts to convince the Americans to resume the afternoon’s baseball venue. Deal and Sisler held fast in their refusals and eventually the government bureaucrats departed in a barely controlled fit of anger. Deal sensed that the failed Sunday morning meeting would be most difficult for their hosts to explain to their government superiors (and perhaps even to Fidel himself).

The bottom-line result of the eventful weekend — which first saw Fidel take the mound and later witnessed chaos overtake the ballpark — was the beginning of the end for International League baseball on the communist-controlled island. But the death knell would be slow to peal for the Havana franchise. The International League’s Governors’ Cup championship playoffs (with surprising third-place finisher Havana defeating the fourth-place Richmond Vees) and a Little World Series showdown with the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association (featuring a hot prospect named Carl Yastrzemski) would both transpire in Havana later that same fall. And Fidel the baseball fan was of course a fixture at both events, although frequent reports of Comandante Castro and his comrades toting firearms, strolling uninvited inside and atop the dugouts, and even intimidating first Richmond and later Minneapolis ballplayers with threats of violent intervention have likely been mildly (if not wildly) exaggerated.

By mid-season of 1960 Castro’s expropriations (both actual and threatened) of U.S. business interests on the island, as well as violent outbursts of anti-government political resistance (“terrorism”) on the streets of Havana (with numerous reported destructive explosions spread throughout the city), convinced International League officials and their Washington backers finally to pull the plug on the half-dozen-year reign of the league’s increasingly beleaguered Havana franchise. On July 8, 1960 (while on a road trip in Miami), the proud Sugar Kings (now managed by Tony Castaño and featuring future big leaguers Mike Cuéllar, Orlando Peña, and Cookie Rojas) were closed down by the league’s reigning fathers and relocated literally overnight to the northern climes of Jersey City.

The True Legacy

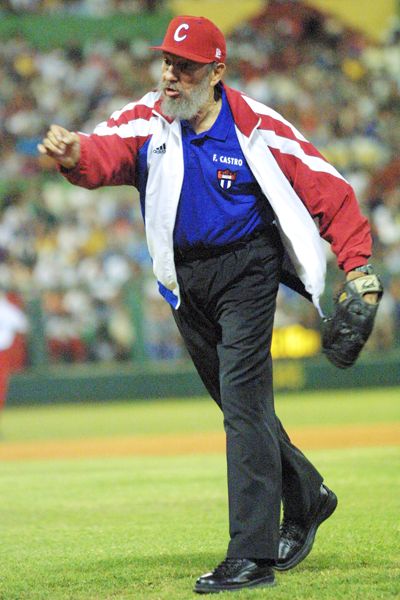

Fidel’s appearance with the Barbudos team was strictly a onetime event. “El Jefe” did not pitch regularly with any team in any version of the “Cuban League” — a distortion erroneously reported by several stateside sources, most infamously by San Francisco’s Blue Marlin Corporation and by ESPN gurus as a featured centerpiece of calculated commercial advertising campaigns. Fidel did continue over the next decade and more to play informally in frequent pickup games with his inner circle of revolutionary colleagues. Biographer Quirk reports that Camilo Cienfuegos was able to maintain favor with Fidel for a time largely because of his ball playing skills. (The ever-popular Major Cienfuegos became an apparent liability, however, within a year of the January 1959 revolutionary takeover and soon disappeared under mysterious circumstances on a solo flight between Camagüey and Havana in late 1959.) Even Che Guevara (an Argentine, who preferred soccer) and brother Raúl (who showed little raw athletic skill or sporting interests that could match Fidel’s) were occasionally photographed in military fatigues or T-shirts and jeans taking their enthusiastic “cuts” during batting exhibitions before Cuban League games of the early ‘60s. Fidel himself made numerous such exhibition appearances in Havana, Santa Clara, Cienfuegos, Matanzas, and elsewhere around the island.

Fidel’s appearance with the Barbudos team was strictly a onetime event. “El Jefe” did not pitch regularly with any team in any version of the “Cuban League” — a distortion erroneously reported by several stateside sources, most infamously by San Francisco’s Blue Marlin Corporation and by ESPN gurus as a featured centerpiece of calculated commercial advertising campaigns. Fidel did continue over the next decade and more to play informally in frequent pickup games with his inner circle of revolutionary colleagues. Biographer Quirk reports that Camilo Cienfuegos was able to maintain favor with Fidel for a time largely because of his ball playing skills. (The ever-popular Major Cienfuegos became an apparent liability, however, within a year of the January 1959 revolutionary takeover and soon disappeared under mysterious circumstances on a solo flight between Camagüey and Havana in late 1959.) Even Che Guevara (an Argentine, who preferred soccer) and brother Raúl (who showed little raw athletic skill or sporting interests that could match Fidel’s) were occasionally photographed in military fatigues or T-shirts and jeans taking their enthusiastic “cuts” during batting exhibitions before Cuban League games of the early ‘60s. Fidel himself made numerous such exhibition appearances in Havana, Santa Clara, Cienfuegos, Matanzas, and elsewhere around the island.

Fidel’s influence on Cuban baseball nonetheless remained enormous after the successful military takeover by his July 26 Movement in January 1959. It was the already deteriorating relationships between Washington and the Cuban government during that very year, and the one that followed, that more than anything led to the sudden relocation of the Cuban International League franchise in July 1960 from Havana to Jersey City. In turn, that decision to strip Cuba of its professional baseball franchise may — as much as anything else in the early stages of the Cuban Revolutionary regime — have worked to sour Fidel Castro on the United States and its (at least from the Cuban point of view) blatant imperialist policies. After the folding of the Havana professional ball club Fidel reestablished baseball on the island (in 1962) as a strictly amateur affair, and under his revolutionary government a new “anti-professional” baseball spirit soon came to dominate throughout Cuba.

Legislation to ban amateur sports was one of the earliest achievements of the Castro government and it laid the foundation for modern-era Cuban baseball. Events surrounding the transition from professional to amateur status in Cuba’s top baseball league unfolded rapidly in the spring and summer of 1961, slightly more than two years after Fidel’s rise to power. As expatriate Cuban scholar Robert González Echevarría sees it, the revolutionary government was improvising under pressure and this might indeed be a fair analysis. González Echevarría notes that it was one thing for the revolutionary government to wipe away memories of Cuba’s political history (of which most citizens at best may not have been well versed) but yet quite another to supplant the island’s cherished cultural traditions (and thus also its deep-seated collective memories) surrounding the institutions of amateur and professional baseball.12

The first step was the creation in February 1961 of a revamped sports ministry labeled INDER (Instituto Nacional de Deportes, Educación Fisica y Recreación) to assume the role of Batista’s old DGND (Dirección General Nacional de Deportes) and designed to oversee all of Cuba’s future “socialistic” sporting activities.13 A mere month later INDER (translated as “National Institute of Sports, Physical Education and Recreation”) had legislated with its National Degree Number 936 what amounted to a total ban on all professional athletic competitions, including most prominently the once-popular winter league affiliated with U.S. organized baseball, and also announced plans for an annual amateur national championship to begin within the coming year. Another novel innovation was the decision that there would never be any admission charges for sporting contests, a policy that lasted almost to the end of the 20th century.

Two additional famed appearances on the baseball by Cuba’s new inspirational leader were those in which “El Comandante” took full advantage of some carefully staged “theater” and smacked the first “official” base hits of the inaugural two revamped National Series seasons. The historic initial season staged in the spring of 1962 lasted little more than a full month and followed by less than nine months the clandestine U.S.-backed invasion attempt at the Bay of Pigs. An opening set of league games was celebrated in Cerro Stadium before 25,000 fans on Sunday, January 14, 1962 and Communist Party First Secretary (then still his official title) Fidel Castro provided a lengthy speech and then stepped to the plate in his traditional military garb to knock out a ceremonial “first hit” against Azucareros starter Jorge Santín. When the actual ballplayers took the field, Azucareros (The Sugar Harvesters) blanked Orientales 6-0 behind three-hit pitching from Santín.14 A widely reprinted photograph (reproduced in my earlier SABR BioProject essay covering “The Cuban League”) of Supreme Leader Castro stroking a season’s first base hit off Azucareros pitcher Modesto Verdura (not Santín) records events occurring in the same park on opening day of National Series II later in the same year. The photo reproduced in this article captures the original first series landmark base knock.

Fidel was later often rumored to have a heavy hand when it came to micro managing the successful national team that from the late ‘60s on dominated international competitions such as IBAF (International Baseball Federation) world championships, Pan American Games and Central American games tournaments, and (after 1992) gold medal competition Olympic Games baseball tournaments. There is sufficient evidence that these claims were more than rumors.15 All doubt of Fidel’s influences over the Cuban national team were erased for this author when I was actually on the immediate scene for one phone call that seems to verify Fidel’s role as apparent national team “pseudo general manager.”

Possessing a press pass at the July 1999 Pan American Games in Winnipeg (the first major post-1970s IBAF-sanctioned international event featuring professional ballplayers as well as wooden rather than aluminum bats), I had approached the Cuban dugout to chat briefly with Cuban league commissioner Carlitos Rodríguez 45 minutes before the gold medal square-off between the Cuban and Americans. Thirty seconds into our chat Carlitos’ cellphone rang and after answering he hurriedly excused himself and retreated to the far end of the dugout. At the end of the five-minute chat in which the commissioner barely uttered a word, Carlitos would acknowledged to me that “el jefe” had called with some last-minute directions about lineups, pitching assignments, and game strategy.

The plan for building strong national amateur squads drawn from domestic league play soon proved a resounding success. Across four-plus decades under Fidel’s leadership, the Cuban regime ironically found in baseball its one proven arena for impressive international triumphs. For 40 full years (beginning with the 1969 IBAF World Championship in Santo Domingo and stretching to the second MLB-sponsored World Baseball Classic in 2009), Cuban teams would dominate world amateur competitions, and few (if any) other achievements of the Cuban Revolution have provided nearly as hefty a source of either bolstered national identity or marked international successes. In the astute phrasing of one noted U.S.-based Cuban cultural historian (Louis A. Pérez Jr., from the University of North Carolina), under Fidel Castro’s regime, baseball — the quintessential American game — has most fully served the Cuban Revolution — the quintessential anti-American embodiment.16

Perhaps the most balanced view of Fidel’s sporadic ball-playing comes in a ‘60s-era book produced by American photojournalist Lee Lockwood (Castro’s Cuba, Cuba’s Fidel, 1967). Lockwood’s groundbreaking portrait of Castro is drawn through hours of in-depth interviews (transcribed in careful detail) on far-ranging topics (viz., his assessments of his island nation, his own enigmatic personality, and the world at large), as well as a collage of the journalist’s rare candid photographs. The single reference to baseball in this entire 300-page tome is a two-page spread featuring photos of Raúl batting (“a competent second baseman, he is the better hitter”) and Fidel pitching (“Fidel has good control but not much stuff”). Both men are captured by Lockwood’s lens in ball caps and informal ball-playing gear. In an interview segment several pages later Fidel comments effusively on his life-long love for sport, emphasizing basketball, chess, deep-sea diving and soccer as his lasting favorites. He stresses his high school prowess in basketball and track and field (“I never became a champion … but I didn’t practice much.”). But there is nary a mention of the national game of baseball.

It is clear from historical records that Fidel was an accomplished and enthusiastic athlete as a precocious youngster. His many biographers underscore his repeated use of schoolboy athletics (especially basketball, track and baseball) to excel among fellow students. But Fidel’s consuming interest and latent talent was never foremost in baseball itself. His strong identification with the native game after the 1959 Revolution — he followed the Sugar Kings as dedicated fan, staged exhibitions before Cuban League games, and played frequent pickup games with numerous close comrades — was perhaps more than anything else an inevitable acknowledgment of his country’s national sport and its widespread hold on the Cuban citizenry. It was also a calculated step toward utilizing baseball as a means of besting the hated imperialists at their own game. And baseball was early on also seen by the Maximum Leader as an instrument of revolutionary politics — a means to build revolutionary spirit at home and to construct ongoing (and headline-grabbing) international propaganda triumphs abroad. Fidel may not have exercised much control over his fastball in long-lost schoolboy days. But he eventually proved a natural-born expert (a true “phenom”) at controlling baseball (the institution) as a highly useful instrument for carefully building his revolutionary society and also for maintaining his propaganda leverage in worldwide Cold War politics.

Fidel and baseball remained inevitably linked across the 49 years of Castro’s active rule in Revolutionary Cuba, and the Maximum Leader would inevitably change the face and focus of the island’s baseball fortunes just as he dramatically changed all else that constituted Cuban society. But it was only as political figurehead and Maximum Leader — not as legitimate ballplayer — that Fidel Castro emerged as one of the most remarkable figures found anywhere in Cuban baseball history. As a pitcher he was perhaps never more than the smoky essence of unrelenting myth. He certainly wasn’t Cuba’s hidden Walter Johnson or Christy Mathewson, or even its latter-day Dolf Luque or Conrado Marrero; his role was destined to be much more akin to the shadowy and insubstantial Abner Doubleday, or perhaps even the promotion-wise and always market-savvy A.G. Spalding.

Cooperstown Hall-of-Famer Monte Irvin, who played for Almendares in the 1948-49 Havana winter league, once quipped that if he and other Cuban leaguers of the late ‘40s had known that the young student who hung around Havana ballparks had designs on being an autocratic dictator, they would have been well served to make him an umpire. Perhaps former U.S. Senator Eugene McCarthy (EFQ, Volume 14:2) had the more appropriate role in mind — that of baseball czar and big league commissioner. Without ever launching a serious fastball or ever swinging a potent bat, Fidel was nonetheless destined — like Judge Landis north of the border a generation earlier — to have a far greater impact on his nation’s pastime then several whole generations of leather-pounding or lumber-toting on-field diamond stars. As McCarthy so astutely observed, an aspiring pitcher with a long memory, once spurned, can indeed be a most dangerous man.

Last revised: March 25, 2016

Sources

Bjarkman, Peter C. A History of Cuban Baseball, 1864-2006 (Jefferson, NC and London: McFarland & Company Publishers, 2007.) [See especially Chapter 9: “The Myth of Fidel Castro, Barbudos Ballplayer”]

Bjarkman, Peter C. “Fidel on the Mound: Baseball Myth and History in Castro’s Cuba” in: Elysian Fields Quarterly 17:1 (Summer 1999), 31-41.

Bjarkman, Peter C. “Baseball and Fidel Castro” in: The National Pastime: A Review of Baseball History, Volume 18 (1998), 64-68.

Castro, Fidel. Fidel Sobre El Deporte (Fidel on Sports). Havana, Cuba: INDER (National Institute for Sports, Physical Education and Recreation), 1975. (Containing excerpts from speeches and publications by the Maximum Leader, providing the most comprehensive source on Fidel’s own comments regarding sports and athletics in socialist society)

Deal, Ellis F. (“Cot”). Fifty Years in Baseball — or, “Cot” in the Act (Oklahoma City, Oklahoma: self-published, 1992.)

Hoak, Don with Myron Cope. “The Day I Batted Against Castro” in: The Armchair Book of Baseball. Edited by John Thorn. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1985), 161-164. (Originally appearing in Sport, June 1964)

Kerrane, Kevin. Dollar Sign on the Muscle — The World of Baseball Scouting (New York and Toronto: Beaufort Books, 1984.)

Lockwood, Lee. Castro’s Cuba, Cuba’s Fidel (New York: Vintage Books, 1969.) (Best English source for Fidel’s personal comments on sports and athletics in socialist society)

McCarthy, Eugene J. “Diamond Diplomacy” in: Elysian Fields Quarterly 14:2 (1995), 12-15.

Oleksak, Michael M. and Mary Adams Oleksak. Béisbol: Latin Americans and the Grand Old Game (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Masters Press, 1991.)

Pettavino, Paula J. and Geralyn Pye. Sport in Cuba: The Diamond in the Rough (Pittsburgh and London: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1994.)

Rucker, Mark and Peter C. Bjarkman. Smoke — The Romance and Lore of Cuban Baseball (New York: Total Sports Illustrated, 1999.) (cf. especially pp. 182-204)

Santamarina, Everardo J. “The Hoak Hoax” in: The National Pastime 14. Cleveland, Ohio: Society for American Baseball Research, 29-30.

Senzel, Howard. Baseball and the Cold War — Being a Soliloquy on the Necessity of Baseball in the Life of a Serious Student of Marx and Hegel From Rochester, New York (New York and London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1977.) (An engaging if largely fictionalized account of July 26, 1959, Havana ballpark episode and its full aftermath)

Thorn, John and John Holway. The Pitcher, The Ultimate Compendium of Pitching Lore (New York: Prentice-Hall, 1987.)

Truby, J. David. “Castro’s Curveball” in: Harper’s Magazine (May 1989), 32, 34.

Wendel, Tim. Castro’s Curveball: A Novel (New York: Ballantine, 1999.) (The most free-ranging fictional treatment of the fictional Fidel Castro pitching legend)

Fidel Castro Biographies

Bourne, Peter G. Fidel: A Biography of Fidel Castro (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1988.)

Castro, Fidel (with Ignacio Ramonet). Fidel Castro: My Life, A Spoken Autobiography (New York: Scribner’s, 2009.)

Dubois, Jules. Fidel Castro, Rebel-Liberator or Dictator? (Indianapolis and New York: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1959).

Geyer, Georgie Anne. Guerrilla Prince: The Untold Story of Fidel Castro (Boston and London: Little, Brown and Company, 1991.)

Halperin, Maurice. The Rise and Decline of Fidel Castro: An Essay in Contemporary History(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972.)

Krich, John. A Totally Free Man—An Unauthorized Autobiography of Fidel Castro (A Novel) (Berkeley, CA: Creative Arts Books, 1981.) (A fictional account filled with unsubstantiated references to Castro’s ball-playing episodes)

Matthews, Herbert L. Fidel Castro (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1969.)

Quirk, Robert. Fidel Castro (New York and London: W.W. Norton and Company, 1993.) (Paperback Edition, 1995)

Szulc, Tad. Fidel: A Critical Portrait (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1986.) (The most complete personal portrait)

Notes

1 Earlier versions of much of this material have appeared in Peter Bjarkman, A History of Cuban Baseball, 1864-2006 (Chapter 9) as well as in Elysian Fields Quarterly 17:1 (Summer 1999) and The National Pastime 18 (1998). See the above references for specific source details.

2 Roberto González Echevarría also eloquently makes the case (The Pride of Havana, pp.352-353) for the unique status of Fidel’s baseball connections: “There has never been a case in which a head of state has been involved so prominently and for such a long period in a nation’s favored sport as Fidel Castro has been with baseball in Cuba.”

3 This essay is of course not a full or even partial biographical treatment of one of the past century’s most complicated historical personalities. It is a “baseball biography” only (as in fact are all the other essays published within the SABR Biography Project) and is aimed primarily at deconstructing the many unfounded myths and legends that have so often been connected to the founder and leader of Cuba’s socialist/communist revolution. A secondary aim is to underscore and explain the rather considerable impact that Castro actually had on the game of baseball as it has developed in Cuba over the past five decades. For those interested in fuller biographical details a list of the best sources is included above. In brief the important details of Fidel’s personal life can be summarized as follows:

He was born as Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz on August 13, 1926 in rural eastern Cuba (in the town of Birán) as the illegitimate son of wealthy farmer and landowner Angel Castro (an immigrant of peasant stock from the Spanish province of Galicia); his mother Lina Ruz González was serving as a maid in Angel’s home at the time when Fidel was born as Angel’s fifth child (and third with Lina, whom he eventually married). Fidel’s 11 siblings eventually included younger brother Raúl Castro Ruz (born June 3, 1931) who succeeded him as both President and Prime Minister in February of 2008. Two large ironies surround Fidel’s birthplace and date: the former (place) was less than 25 miles from the site where Cuba’s other great political hero José Martí perished in battle with Spanish government forces on May 19, 1895; the latter date (like that of many Cuban ballplayers over the years) is probably not precisely correct. Fidel has always insisted that he was born on August 13, 1926, but biographer Robert Quirk has reported that several of his sisters frequently stated he was in fact born one year later and that his parents moved the date up so that he could begin schooling 12 months ahead of schedule. Thus various sources disagree on an acceptable birth year (1926 or 1927) although the calendar day seems indisputable.

While Fidel reigned as supreme leader in Cuba from January 1, 1959 until health issues forced him to step down from formal office on February 24, 2008, he did not actually assume the official position as Cuba’s 16th prime minister until February 16, 1959, or as the nation’s 15th president until December 2, 1976. He was First Secretary of the Cuban Communist Party (the true seat of power) from July 1961 through April 19, 2011 (when he also ceded the latter position to his brother Raúl, longtime commander of the Cuban military).

Fidel has married twice, to Mirta Diaz-Balart (1948-1955) and Dalia Soto del Valle (1980 to present). Of his nine children, only one, Fidel Angel Castro-Balart (known as “Fidelito” and a university professor and long-recognized expert in the field of nuclear physics who chaired Cuba’s Atomic Energy Commission from 1980 to 1992) was a product of his first marriage. Of five children produced by his second marriage, the best known is Antonio Castro-Soto (“Tony”), a Paris-trained orthopedic surgeon who long served as the Cuban national baseball team physician and is currently a Vice President of both INDER and the International Baseball Federation (IBAF). Tony Castro has been a major player over the past several years in the IBAF movement to have baseball re-established as an official Olympic sport.

4 Fidel was not the last Cuban pitching prospect to have his talents vastly exaggerated by North Americans (writers, scouts, player agents, or commercial advertisers) hoping to gain something from such exaggerations and at the same time knowing they could likely get away with saying almost anything that they thought others wanted to hear about a dark and mysterious corner of the baseball universe. Aroldis Chapman was sold as “the greatest pitcher ever to come off the island” when being pushed by his agent toward an eventual $30 million contract (he has been dropped from the Cuban national team for shoddy performance on the eve of the Beijing Olympics). More egregious cases of late have been those of failed pitching prospects Geraldo Concepción (Chicago Cubs) and Noel Argüelles (Kansas City Royals) who have struggled mightily in their minor-league trials after inking windfall contracts resulting from inflated scouting reports.

5 In October 1998 I wrote a note to NBC broadcaster Bob Costas questioning his on-air repeating of the Fidel “prospect legend” during that fall’s World Series broadcasts. Costas was kind enough to return a postcard which I quote here in its entirety: “Peter, Thank you for the articles. Interesting stuff. The myth was always appealing — Don Hoak must have sensed that! All the best — Bob Costas.”

6 For fuller support of this claim see my SABR BioProject essay on “The Cuban League.” A more detailed collection of evidence is found throughout my 2007 McFarland book cited above.

7 Hoak and Cope, 164 (in the 1985 reprint edition of The Armchair Book of Baseball, edited by John Thorn).

8 Santamarina, 29.

9 Tom Jozwik, “A Worthy Successor to the Firesides,” in: The SABR Review of Books, Volume 1 (1986), 67-68. Not to be left out of the mix, noted travel writer Tom Miller also repeats and thus apparently buys) the Hoak-Castro tale in his well-received travel book Trading with the Enemy: A Yankee Travels through Castro’s Cuba (New York: Atheneum, 1992), recounting the details (p. 289) with due wonder and the voice of authority.

10 Kerrane, 268.

11 If Fidel was not a pitcher for the University of Havana varsity nine, as so often reported, he did apparently do some actual pitching while on the university campus. El Mundo for 28 November 1946 carries a game report and minimal box score for the university’s intramural championship contest (played one day earlier) between the faculties (schools) of Commercial Sciences and Law, in which one F. Castro hurled for the latter squad. The full box score (reproduced in my 2007 book A History of Cuban Baseball, pages 313-314.) may be the only existing evidence containing game statistics for Fidel Castro’s altogether abbreviated and unglamorous collegiate baseball career. As the losing hurler, Fidel struck out four, walked seven, yielded five hits and five runs, and hit one batter in his complete-game losing effort.