April 25, 1901: Tigers stage 9th-inning comeback in AL opener

More than a century ago, the Detroit Tigers staged the biggest ninth inning come-from-behind-victory engineered in baseball. It still stands.1

More than a century ago, the Detroit Tigers staged the biggest ninth inning come-from-behind-victory engineered in baseball. It still stands.1

The inaugural 1901 American League season was scheduled to open in Detroit on Wednesday, April 24, but rain just before game time prevented play. The next day was sunny, warm for April, and “a day to make a well man glad to be alive, and a sick man feel the tingle of returning health.”2

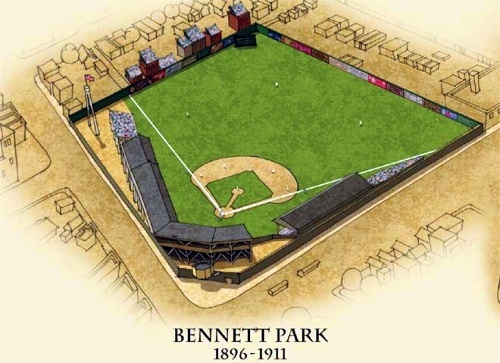

The largest throng to yet attend a ball game in Detroit overflowed Bennett Park. The players paraded to the park in carriages from the Russell House Hotel, and by the time they arrived, a mass of 10,0233 had overflowed into the outfield. The overflow necessitated the imposition of a ground rule— any balls into the outfield crowd would be doubles.

The visiting Milwaukee Brewers4 were introduced first to a polite reception. The Tigers, in red coats, then lined up, marched a few steps toward the grandstand, and removed their caps in a salute to the fans. After the teams warmed up, “Oom Paul,” the canine Detroit mascot, made an appearance, and the local Elks club presented a loving cup to Tiger owner James Burns and manager George Stallings, both fellow Elks. A local legislator, Jacob Haarer, filled in for the mayor and threw out the first pitch to Charlie Bennett, a retired catcher and Detroit baseball legend for whom Bennett Park was named.5

After a band played a prophetic “There’ll be a Hot Time in the Old Town To-night,” Brewer leadoff hitter Irv Waldron hit a grounder to Kid Elberfeld at shortstop, who “made a gorgeous fumble.”6 Billy Gilbert followed with a base hit and Bill Hallman sacrificed both runners up a base. Tiger third baseman Jim “Doc” Casey then forced Waldron at the plate on John Anderson’s ground ball. Anderson and Gilbert attempted a double steal, but Elberfeld’s return throw to catcher Fred Buelow caught Gilbert for the third out.

Casey led off for Detroit. Wearing the club’s new uniform, with a small red tiger on the cap, he accepted a basket of flowers from the Elks on arrival at the batter’s box. After he bowed in appreciation and handed off the flowers, he grounded back to the Milwaukee pitcher, Pink Hawley. The Tigers managed a hit and stolen base by Bill “Kid” Gleason, but didn’t score.

Wid Conroy opened the Brewers’ second with a single. He went to third on an out by playing manager Hugh Duffy, but first baseman Frank Dillon made a bad throw in an attempt catch Conroy, who advanced and scored the first run of the game. With two outs Brewer catcher Tom Leahy reached second base on a wild throw by Elberfeld; he then scored as Tiger left fielder Ducky Holmes muffed a fly ball by Hawley when Holmes encountered the overflow crowd in the outfield. After another Elberfeld error, the Brewers were retired, but they had two runs. The four Detroit errors made it look to the Detroit Tribune reporter that the Tigers were hypnotized or suffering from an attack of stage fright. In any case they were playing “wretched ball.”7

Detroit failed to score in its half of the second, and Milwaukee, already leading 2-0, added five more runs in the third on another error, four hits, a walk and a sacrifice. Stallings replaced starting pitcher Roscoe Miller with Emil Frisk during the uprising. Milwaukee’s seven-run lead held as the Tigers failed to score in their half of the third. Brewer captain and third baseman Jimmy Burke made the defensive play of the game here, stopping Buelow’s hot grounder and throwing him out at first.8

Detroit managed to shut down the Brewers in the fourth, then scored their first run on an error, followed by Dillon’s ground rule double into the crowd. Elberfeld then knocked in Dillon with another ground rule double. The Tigers pecked away with a run in the fifth, and after six innings it was 7-3, Milwaukee.

The Brewers, though, lengthened this to 10-3, plating three runs after two outs in the seventh. Duffy apparently considered the lead safe and replaced Hawley with Pete Dowling, a 24-year-old left-hander, who “had been Detroit’s jonah all last season.”9 Dowling held form through the Detroit seventh, allowing only a walk.

Milwaukee padded its lead to 13-3 in the eighth, but the Tigers nicked Dowling for a run in their half, using another ground-rule double by Dillon. Still plugging away, Frisk got the Brewers one-two-three in the top of the ninth.

With their team down 13 to 4 and the Tigers not having shown them much, some Detroit fans had left by the bottom of the inning. But there were still enough for overflow in the outfield, and Casey led off with another ground rule double. Jimmy Barrett beat out a slow grounder to third. Gleason then singled to center to score Casey. The crowd livened, as Holmes, Dillon, and Elberfeld all doubled. “The tremendous shouts that were sent up evidently unnerved Pitcher Dowling. As each hit went out a mighty cheer went up that was enough to make most any one lose his nerve.”10 Five runs were now in; it was 13-9.

By this time Duffy was feeling uneasy. He came in from center field and replaced Dowling with Bert Husting. Husting, who wasn’t fully warmed up, uncorked a wild pitch, but settled down to retire Kid Nance for the first out.

As the inning progressed, the crowd had pressed closer to the diamond. Duffy protested, and umpire Jack Sheridan ordered the fans back. The game was delayed a few minutes as the Detroit players “ran out to push back the throng in order to afford the Milwaukee outfielders a chance to chase some of the terrific drives that were being sent out.”11 Although the delay gave Husting a chance to warm up, he walked the next batter, Buelow. Frisk followed with a single to left, scoring Elberfeld. 13-10.

Casey was next up and beat out a bunt down the third base line to load the bases. Husting was able to fan Barrett for the second out. Gleason then hit a hard shot to Burke at third base. But Burke botched the play and Buelow scored to make it 13-11. It quickly became 13-12 when Burke couldn’t get an out on Holmes’ slow roller and Frisk scored.

Dillon was up again. The big first baseman already had three ground-rule doubles on the day, and made it a fourth when he ripped a 2-2 pitch into the crowd in left field. Casey and Gleason romped home with the tying and winning runs.

Dillon was up again. The big first baseman already had three ground-rule doubles on the day, and made it a fourth when he ripped a 2-2 pitch into the crowd in left field. Casey and Gleason romped home with the tying and winning runs.

Pandemonium broke loose at Bennett Park. The crowd quickly overtook the field and “a dozen crazy fans picked [Dillon] up and carried him about the diamond on their shoulders, while everybody assured his neighbor that he had never in his life seen anything so wonderful.”12 The Detroit Tribune writer waxed rhapsodic: “The riotously jubilant vocalization of 10,000 throats let loose in one simultaneous sub-aerial explosion, [making] the old earth’s enveloping atmosphere heave and billow clear to its surface 50 miles away, and no doubt it is tumultuous yet.”13

And as of this writing in late 2015, the Tigers’ feat on their first day of play in the brand-new American League is still the biggest ninth inning game-winning comeback in major league baseball history.

Across Lake Michigan in Milwaukee, there was astonishment as the wire reports rolled in. Brewer secretary Fred Gross was in the process of preparing a telegram recounting the victory to club president Matthew Killilea, who was in Arizona for health reasons. Before Gross could send the telegram he received a phone call telling him the Tigers had won the game. Gross assured the caller there had to be a mistake, as Detroit would have had to score ten runs to win. When told this was exactly what had happened, Gross replied that he needed to hear from Duffy, then presupposed a reason for the apparent collapse: “The men all must be injured for a team to make ten runs in one inning. I will wire Duffy to take care of the men until they recover.”14

Only the Brewers’ pride had been injured by the epic Detroit rally. Although some in Milwaukee talked of a protest because of crowd interference, the Evening Wisconsin was philosophical: “It was indeed hard for Duffy to lose a game in that manner, but such is baseball and will ever be that way. It only goes to prove once more that baseball is the one sport that is absolutely honest in every line of playing.”15

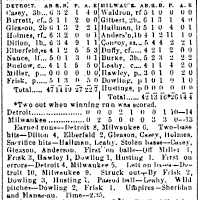

Box score

As a box score for this 1901 game is not yet available at Retrosheet.org or Baseball-Reference.com, the box score from the May 4, 1901, edition of Sporting Life is reproduced below. (For reasons lost in the mists of time Sporting Life showed Milwaukee as batting in the bottom of the innings, even though Detroit, as the home team, did. This inconsistency also appears from time to time in other, but not all, Sporting Life box scores.)

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank fellow SABR members Marc Okkonen and Jonathan Frankel (and any others whose emails I might have accidentally deleted) for help in obtaining material for this article.

Notes

1 Carl Bialik, “Baseball’s Biggest Ninth-Inning Comebacks,” Wall Street Journal, July 28, 2008; blogs.wsj.com; “Tigers’ Ten Greatest Games,” This Great Game: The Online Book of Baseball History, thisgreatgame.com.

2 “Base Ball As A Barometer of Fans,” Detroit Tribune, April 26, 1901, 5

3 Scott Ferkovich, “Bennett Park (Detroit),” SABR Baseball Biography Project, sabr.org. Bennett Park was built in 1896 with a capacity of 5,000. Seats were added for the 1901 season to bring capacity to 8,500. Ibid.

4 The 1900 Brewers finished second in the then-minor-circuit American League. Over the 1900-01 offseason, however, league president Ban Johnson pushed the AL to at least nominal parity with the “senior circuit” National League, which had held major league status since 1876. Brewer owner Henry Killilea was reluctant to spend the funds necessary to recruit National League players to Milwaukee; the team also lost 1900 manager Connie Mack to American League rival Philadelphia. With the game chronicled here typical of Milwaukee’s competitiveness, the club stumbled to a last-place, 48-89 finish in 1901. Johnson moved the franchise, which became the Browns, to St. Louis for 1902. Major league baseball didn’t return to Milwaukee until the arrival of the Braves from Boston for the 1953 season. Baseball-Reference.com; Donald Dewey and Nicholas Acocella, The Ball Clubs. New York: Harper Perennial, 1996, 307-08.

5 Ferkovich, “Bennett Park (Detroit).”

6 “Ten Runs Won in the Ninth,” Detroit Free Press, April 26, 1901.

7 “Ten Runs in Ninth,” Detroit Tribune, April 26, 1901, 1.

8 “Ten Runs . . .,” Detroit Free Press, April 26, 1901.

9 “Between the Innings,” Detroit Free Press, April 26, 1901.

10 “10,000 People See Great Batting Rally,” Detroit Free Press, April 26, 1901.

11 Ibid.

12 “Ten Runs in Ninth,” Detroit Tribune, April 26, 1901, 1.

13 “Base Ball As A Barometer Of Fans,” Detroit Tribune, April 26, 1901, 5.

14 “Thirteen A Hoodoo,” Evening Wisconsin, April 26, 1901.

15 Ibid.

Additional Stats

Detroit Tigers 14

Milwaukee Brewers 13

Bennett Park

Detroit, MI

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.