April 26, 1901: Baltimore Orioles win home opener in a new major league

In late January of 1901, American League President Ban Johnson convened a series of organizational meetings at the Grand Pacific Hotel in Chicago. The purpose of the gatherings was to iron out the final details in preparation for the launching of his new major league. Seven years earlier, Johnson, a Cincinnati sportswriter, had become president of the Western League, a very competitive minor circuit. In 1900, Johnson changed the name of the loop to the American League. The following year, claiming major-league status, he added teams from Baltimore, Boston, Philadelphia, and Washington.

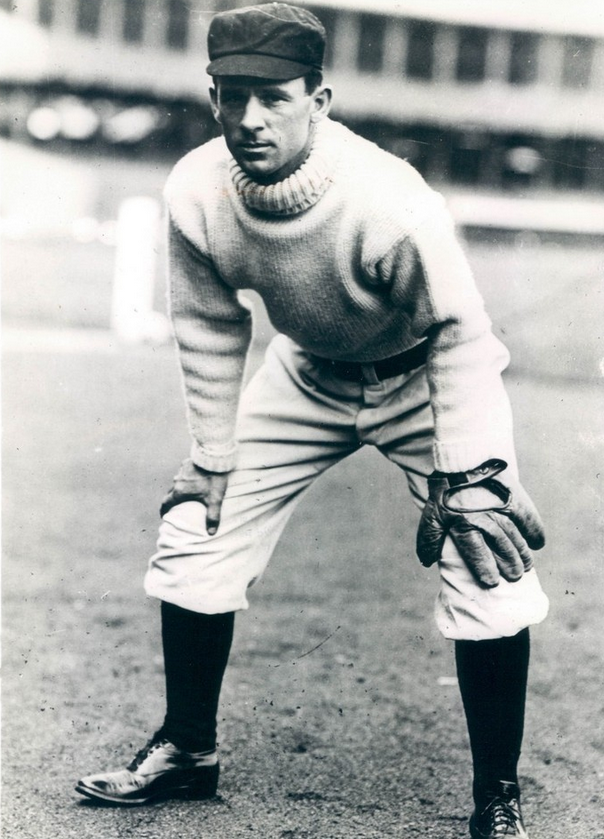

A few weeks before Johnson’s Chicago sessions, the Baltimore contingent elected its own officers and directors and authorized the construction of a ballpark. Third baseman John McGraw, one of the club’s stockholders, would serve as the player-manager.

McGraw’s Orioles, named after two previous major-league franchises in Baltimore, held spring training at Hot Springs, Arkansas. After a few weeks of practice and signing additional players, McGraw’s squad came back to Baltimore in early April to take part in a series of exhibition games.

The Orioles’ Opening Day opponent, the Boston Americans, led by player-manager Jimmy Collins, held their preseason workouts in Charlottesville, Virginia.

Following two consecutive rainouts, the Orioles finally crossed bats with the Americans on April 26, 1901. The game was played at American League Park (Oriole Park IV), located at what is now the southwest corner of Greenmount Avenue and 29th Street.

Beginning at 1 P.M., a procession of nearly 50 carriages started out from the Eutaw House Hotel at the northwest corner of Baltimore and Eutaw streets. American flags were draped from buildings along the parade route as fans of all ages lined the streets. Led by a detail of mounted policemen, the caravan of horse-drawn conveyances included team executives, players from both teams in uniform, sportswriters, politicians, union leaders, and other local baseball enthusiasts.1

More than 10,000 fans, a good-sized crowd for an early twentieth-century major-league game, were waiting at the ballpark. Ropes were strung along both foul lines to hold back the overflow of spectators. Lavish floral arrangements, which would be presented to the players at various stages of the game, lined the perimeter of the grandstands.

After a short practice session followed by the pregame festivities, Ban Johnson tossed out the ceremonial first pitch. Then the Orioles took their positions on the diamond. Joe “Iron Man” McGinnity, recovering from a recent bout of malaria, was the starting pitcher for the Orioles. (He reportedly earned the nickname due to his previous employment in an iron factory.) Beginning his third year in the majors, McGinnity was coming off back-to-back 28-win seasons and a total of more than 700 innings pitched. This durability would be a common theme throughout his career.

McGinnity’s batterymate was Wilbert Robinson. The reliable backstop for Baltimore’s National League champion Orioles, Robinson once caught 26 innings in one day during a tripleheader sweep of the Louisville Colonels in 1896. It would have been 27 except that the third game was called in the eighth inning because of darkness.

Boston’s leadoff hitter, Tommy Dowd, started the contest with a bounder up the middle that McGinnity snagged for the first out. The next batter, Charlie Hemphill, swung down on a ball that landed in front of home plate before bouncing straight up in the air. McGinnity ran in from the pitcher’s box, fielded the ball, then fired to first to catch Hemphill by a step. Hemphill may have been taking a page from the 1890s Orioles playbook by attempting the famous “Baltimore Chop” to get on base.2

McGinnity, using to great effect the side-arm rising curveball he called “Old Sal,” held the opposition scoreless for the first three frames. On the Boston side, pitcher Win Kellum was making his major-league debut. The southpaw hurler had been a 20-game winner with the Western League’s Indianapolis Hoosiers in 1900. Baltimore’s first batter, John McGraw, received a thunderous round of applause that lasted over three minutes as he walked to the plate. The tough New Yorker acknowledged the crowd and greeted Kellum with a double off the top of the right-field fence.

Turkey Mike Donlin followed with a three-base hit over center fielder Chick Stahl’s head that scored McGraw. (Donlin’s turkey-like gait earned him the barnyard moniker.) After a walk to Jimmy Williams, Bill “Wagon Tongue” Keister smacked a double to right that scored Donlin and Williams.3

“A great ovation was given to Robbie and Mac when they stood together in the second inning and were presented with a beautiful floral tribute. Their names were inscribed on yellow and black ribbon which hung from the design” was how one local sportswriter described the tribute the two Orioles received from the fans.4

Baltimore added another run in the bottom of the third on Donlin’s second triple of the game and a fly ball by Williams.

Boston scored in its half of the fourth. Jimmy Collins got things started with a liner between short and third that was good for two bases. With Buck Freeman at bat, Wilbert Robinson tried to pick Collins off second but nobody was covering the bag. The ball sailed into center field, and Collins scampered to third. Freeman knocked Collins in with a base hit to left. Robinson made amends soon after by throwing out Freeman by 10 feet on an attempted steal of second.

In the sixth, Keister drove a triple through the gap in right-center. After a walk to Cy Seymour, the Orioles reverted to some inside baseball. Seymour took off for second as Kellum released his pitch. The batter, Jimmy Jackson, playing in his first major-league game, protected the runner with a swing and a miss. Keister, on third, headed for home as Boston catcher Lou Criger unleashed his peg to second. Criger’s throw was high, allowing Seymour to slide in safely while Keister crossed the plate. Jackson followed with a double that knocked in Seymour for the Orioles’ sixth tally of the game.

After enduring seven innings of one-run ball, the Boston bats began to show signs of life in the eighth. With McGinnity tiring, Criger and Kellum reached base via a double and an infield hit. An RBI single by Dowd and a fly ball by Collins accounted for a pair of Boston runs before McGinnity retired the side.

In the Orioles’ half of the inning, Keister ignited the offense again with a single to center. The next batter, Seymour, bunted for a base hit. Jackson followed with an RBI double. After a walk to Frank Foutz, Robinson swatted a grounder to third that Collins missed, allowing two runs to score. A pair of force outs pushed Foutz home with the Orioles’ final run of the game.

Things got a bit dicey for Baltimore in the top of the ninth. With one out, Hobe Ferris hit a ball past first baseman Foutz. Williams, at second, backed up the play, but threw wildly to first, allowing Ferris to advance a base. After Criger got a hit, rookie catcher Larry McLean pinch-hit for Kellum and smacked a two-bagger that scored Ferris. Dowd followed with a grounder that Keister fumbled, and Criger came home. McLean scored on a fly ball before Stahl grounded out to end the game. Baltimore had won its first American League game, 10-6.

There were many defensive standouts that day. The Boston outfield of Dowd, Stahl, and Hemphill played too shallow on several occasions, but otherwise made some stellar grabs. For Baltimore, center fielder Jimmy Jackson hauled in everything in his territory, including a sensational shoestring catch off the bat of Collins in the sixth. The best play of all was made by McGraw in the third inning. Dowd sent a towering fly ball close to the third-base grandstand. McGraw, weaving his way through the blue-coated policemen stationed along the rope line, kept his concentration and gathered in the tough popup.

In regard to the Orioles’ starting pitcher the Baltimore American wrote, “For seven innings McGinnity fooled the heavy hitting Bostonians, which was doing so well for a sick man that people are apt to wonder what the Iron Man will do when he quite recovers his health.”5

After the game Boston player-manager Jimmy Collins told reporters, “Our boys will do better work after they get into the strides. You couldn’t judge much by today’s game.”6

Although the 1901 season started off on a good note for Baltimore, the relationship between the manager and Ban Johnson deteriorated rapidly. Due in part to his contempt for Johnson’s American League umpires, McGraw left the Orioles in July of 1902 to join the National League’s New York Giants.

A mass player exodus soon followed, leaving Baltimore unable to put nine men on the field. Johnson asked other American League clubs to send players to Baltimore so the Orioles could play out the schedule. At the end of the 1902 campaign, Baltimore’s American League franchise was transferred to New York. Originally called the Highlanders, this team is now known as the New York Yankees.

Author’s note

The Baltimore newspapers have varying accounts of what Boston runner was thrown out stealing by Wilbert Robinson in the fourth inning, Buck Freeman or Freddie Parent. By comparing the game accounts in the Boston and Baltimore newspapers Freeman was on first base when Parent was put out on a fly ball for the second out in the fourth. Freeman was then caught stealing for the last out of the inning.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes. the author consulted contemporary newspaper articles from the following newspapers: Baltimore Morning Herald, Baltimore Morning Sun, Boston Herald, Boston Journal, and Sporting Life.

Notes

1 The cavalcade traversed the principal streets of the city—Baltimore, Holliday, Lexington, Calvert, Fayette, Howard, Monument, Charles, Huntington Avenue, then finally out to York Road (present-day Greenmount).

2 Baltimore groundskeeper Tom Murphy was known to pack hard clay around the plate at Union Park, the home grounds of the great National League Orioles. When the Orioles batters chopped at the ball it would bounce high off the clay. By the time the opposition could make a play, the runner was usually safe. Whether the team’s groundskeeper in 1901, Marty Lyston, employed the same tactic at American League Park has been lost to history.

3 The true origins of Keister’s unusual nickname are up for debate. Was it his use of the Wagon Tongue model bat or his propensity for salty language? It was quite possibly a combination of the two.

4 “Orioles Made An Easy Start,” Baltimore American, April 27, 1901: 10.

5 “Orioles Made An Easy Start,”

6 “Takes The Crowd,” Boston Globe, April 27, 1901: 8.

Additional Stats

Baltimore Orioles 10

Boston Americans 6

Oriole Park

Baltimore, MD

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.