24 Years Before Jackie Robinson, Charlie Culver Broke Barriers in Montreal

This article was written by Christian Trudeau

This article was published in Spring 2020 Baseball Research Journal

In 1946, all eyes were on the Montreal Royals and Jackie Robinson as he was readying to break baseball’s color line. But 24 years earlier, without any publicity, an African American ballplayer had already played six games for the Montreal team in the Class B Eastern Canada League. Charlie Culver’s presence didn’t ruffle many feathers — except on the semi-pro team that had previously signed him.

In 1946, all eyes were on the Montreal Royals and Jackie Robinson as he was readying to break baseball’s color line. But 24 years earlier, without any publicity, an African American ballplayer had already played six games for the Montreal team in the Class B Eastern Canada League. Charlie Culver’s presence didn’t ruffle many feathers — except on the semi-pro team that had previously signed him.

Background and hiring

Montreal had lost the International League Royals after the 1917 season, leaving the city without a professional team. To fill the absence, several semi-pro leagues had popped up, with many teams vying for the city championship, as well as other towns and cities across Quebec competing for the provincial title. In 1921 Joe Page — a Canadian Pacific Railway employee, baseball promoter, and Chicago White Sox scout — unsuccessfully tried to start a new league with teams in Montreal, Sherbrooke, Granby, Trois-Rivières, and Ottawa.1

The following year, a scaled-down version of the Page project came to life with the creation of the Eastern Canada League in late March 1922. The league would be centered in Montreal with a local team there and rivals to the southwest in Valleyfield, to the west in Ottawa, and to the east in Trois-Rivières. At an early April meeting, it was announced that the league had received a Class B accreditation from the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues.2

With Opening Day set for May 11, teams scrambled frantically to fill their rosters. Naturally, the best players in the local semi-pro leagues were prime candidates, and the first to sign up. One of these was a multi-talented, all-around player, named Charlie Culver.3 Culver had excelled both at the plate and on the mound over his previous two seasons in Montreal, playing mostly at shortstop when not pitching. His success was not surprising given his background: before arriving in Montreal, Culver had played high-level baseball between 1916 and 1920 with two top independent Negro teams: the New York Lincoln Giants and the Philadelphia Red Caps. His teammates had included Joe Williams and Fats Jenkins, among others.4

In September 1919, he landed in Montreal along with Pop Watkins and his Havana Red Sox.5 The following spring the team returned, and Culver was offered a contract to also play with St. Henri, a Montreal team vying for the city championship. During the weekend of May 22–23, Culver not only pitched a complete game for the Havana Red Sox, he then went the distance the next day in a marathon game for St. Henri, eventually losing 6–5 in 20 innings.6

In the United States, Culver had no choice but to play on Negro League teams because black players had been effectively banned from the major and minor leagues. Throughout the twentieth century, there had been attempts to disguise black players as Native American (Jimmy Claxton with the 1916 Oakland Oaks) or Hispanic (many light-skinned Cubans signed by Cincinnati and Washington).7

Somehow, the “gentleman’s agreement” excluding black players does not seem to have reached the Eastern Canada League. When the Montreal management, led by president Fred Gadbois and manager Larry Carmel, started assembling its lineup, Culver was a natural fit. He signed with the team on April 25. The daily newspaper La Presse ran the story the next day, along with a photo, but made no mention of his race or the color line. The article congratulated the team on a solid hiring.8 Other newspapers in Montreal, as well as those outside of the city, did not carry the story.

Nevertheless, over the next few days, two negative reactions were published in the local newspapers. The first had nothing to do with the color line. On April 27, La Presse ran a letter expressing the concerns of a baseball team in St. Hyacinthe, some 70 kilometers (45 miles) east of Montreal. The team, seeking Quebec baseball supremacy, had signed Culver to a contract a month earlier, and had no intention of giving him up. St. Hyacinthe was certainly capable of attracting top talent, both from the province and neighboring regions, with presumably good pay. But the Eastern Canada League played six games a week, while St. Hyacinthe only played on weekends. The letter carefully attacked the Montreal team and the new league, but not Culver himself.9

Then on May 2, the other French-language Montreal daily newspaper, La Patrie, published parts of a long letter it had received which further complained about Culver’s hiring. These concerns were also directed at the new league, but this time made a point of addressing the matter of the color line by pointing out how unusual it would be for a team in Organised Baseball to hire any black player. As such, the letter wonders about the legitimacy of the alleged Class B status for the league:

How can the new organization pretend to be in Organized Baseball, that prohibits hiring colored players on its teams? Aren’t we trying to fool the public in this story?10

While the letter is signed by “a group of baseball fans,” it was evident that this “group” also managed the rival (semi-pro) City league, which stood to lose serious revenue because of the arrival of the professional league.

Those that were the first to ostracize Calvert a few years ago when he arrived in the City league are the same characters who today are offering a king’s ransom to hire him in an organization supposedly in Organized Baseball. Don’t we just want to hurt the City league and baseball in general?11

None of this prevented Culver from getting ready for the Eastern Canada League season. League President Joe Page, keen to properly launch the league, had used his baseball contacts to arrange high profile visits throughout the season, and the Boston Braves were the first in town on April 30. Arriving with most of their regular lineup, they beat Culver’s Montreal team by a score of 7–2. Culver played shortstop, and was penciled in the third spot of the lineup. He amassed two of the four hits against Braves pitcher Jigger Lansing, including a double that was described as the best shot of the day.12 The Boston Globe ran a short article on the game, with no mention of Culver. Interestingly, they (and the league) credited Culver’s double to teammate Delisle.13

If there was any attempt to hide or disguise Culver, it seems to have been a poor one. While touting an exhibition game against Trois-Rivières before the official start of the season, La Presse mentioned that “Cuban pitcher” Charlie Culver was to be on the mound.14 It is not clear if this was a reference to his arrival with the Havana Red Sox — who had no link to Cuba, and used the name as a marketing gimmick — or to his mysterious origins (more on that later). In general, local newspapers didn’t shy away from describing him as black or colored. As for the exhibition game, it was rained out.

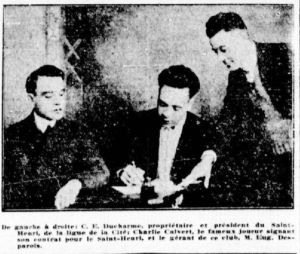

Charlie Culver signs his 1921 contract with the St. Henri semi-pro team. (LA PRESSE)

Playing in the Eastern Canada League

In the late afternoon of Thursday May 11, 1922, in front of about 3,000 fans at Atwater Park in Montreal, Culver took the mound against the visiting Ottawa team. He gave up single runs in each of the first two innings, but a two-run home run by teammate Edward Singher evened the score at 2–2. Culver switched into second gear in the third: slotted in the fifth spot in the lineup, he hit a three-run homer, and blanked Ottawa the rest of the way. Montreal won 7–2, with Culver giving up the two runs on seven hits and a single walk, striking out 10. He added a double to his long ball to finish 2 for 4.15

La Presse ran a short story on the game, not mentioning Culver’s background or race. If there were reactions from the crowd or the teams, they did not make it to print. The article was accompanied by pictures of the two teams as well as the umpires.

The following afternoon, Culver was moved to right field, and while he was limited to one hit in four at-bats, it was a big one. His second home run in two days tied the score at 2–2 in the eighth inning. Montreal sealed the deal in the ninth to beat Ottawa, 3–2.16

On May 13, Montreal completed the sweep against Ottawa with a 6-4 win, as Calvert finished with one hit in two at-bats and a run scored. He sat out the next day, a 3–2 loss at home against Valleyfield.17

On May 15, he was back on the mound, and his teammates gave him an early five-run lead. It was 9–2 in the eighth inning when Culver let his guard down and let in three runs. In total, he surrendered five runs on 11 hits and a walk, striking out three batters. However, for the first time, he was held hitless at the plate in two at-bats, scoring one run and committing an error.18

The next day, he returned to right field, producing a double in three at-bats, scoring three runs in a 8-4 win.19 The final game of the series against Valleyfield occurred on May 17, with Culver managing to go 1–4 in an 11–2 loss.20

Trois-Rivières then came in town for a series starting on May 18, but Culver was not in the lineup. Newspapers of the day ran brief stories focusing mostly on the previous day’s game. No reason was given for Culver’s absence, but he would not return. A few days later, on May 22, Le Nouvelliste de Trois-Rivières reported that “Culver, formerly of Montreal, will be obliged to play for St. Hyacinthe, with whom he had signed a contract at the beginning of the season.”21

Although his name would continue to appear sporadically in the media for his play in semi-pro ball, Charlie Culver’s career in organized baseball was over after six games. Culver appears, absent a first name, in the official statistics of the league. At the plate, he went 6 for 19 with two doubles and two home runs, scoring seven times. On the mound, he was 2–0 with 18 hits and seven runs allowed in 18 innings. He struck out 13 batters and gave two free passes.

Despite their good start, the Montreal team finished last in the league with a 55-69 record. Midseason, Valleyfield moved to Cap-de-la-Madeleine, just across the Saint-Maurice River from Trois-Rivières, which won the pennant with a 69-53 record. The Cap-de-la-Madeleine team then moved to Quebec City for the 1923 season. In 1924, the league added two teams in Vermont, in Rutland and Montpelier, while Trois-Rivières was replaced by a second team based on the island of Montreal. The league rebranded itself as the Quebec-Ontario-Vermont league. The Vermont teams disbanded at mid-season, and the league itself ceased its operations after the season.

Semi-pro leagues in Quebec continued to attract black players in the following years. Chick Bowden, a catcher who had come to Montreal with the Manhattan Giants, eventually settled in Quebec and had a long baseball career across the province. By the late 1920s, Chappie Johnson was sponsoring an all-black team in Montreal leagues, an experience that continued sporadically until 1937, when a team called the Black Panthers was part of the Provincial League. Culver and Bowden alternated playing with these teams and with local teams.22

On Charlie Culver

Quebec newspapers are not especially generous about Charlie Culver’s origins.23 By drawing information from the Seamheads Negro League Encyclopedia and making contact with one of his great-grand-daughters we can produce a rough sketch of his life. He was born on November 17, 1892, in Buffalo, New York, presumably the out-of-wedlock son of Joseph Edwin Culver and an unidentified mother.24 He was thus approaching 30 years of age when he played in the Eastern Canada League in 1922. According to his WWI registration card, by 1917 Charlie was living in New Jersey and working as a porter at Pennsylvania Station in New York City (and, as previously mentioned, playing for the Red Caps, a Negro independent team made up mostly of his coworkers). He was married, although the name of his wife is not reported.25

By 1920 he had made it to Montreal, and shortly after he married Paula Saint-Arnaud, a widow with a young son. Her husband had succumbed to the Spanish flu while serving in the Canadian Army. He adopted her son Gérard, who took the last name of Calvert, and the couple had a son (Joseph, 1924) and a daughter (Dolores, 1927) together. Paula was shunned by her family for marrying a black man. Tragedy struck when Paula passed away in 1930, a victim of a typhoid epidemic.26 Left alone with three children, Culver eventually gave his two youngest, Joseph and Dolores, up for adoption, while Gérard was left to fend for himself.27

Charlie Culver, right, is honored as manager of the 1950 Montreal junior champions. (LE SAMEDI)

Culver seems to have stayed in Quebec for the rest of his life, devoting most of it to baseball. He continued to play semi-pro ball across southern Quebec until the mid-1940s, often as player-manager.28 By the 1950s, he had transitioned to coaching junior baseball in Montreal. According to various voters lists, he seems to have complemented his income with factory work, being listed as a Canadian Vickers employee, then later as a foreman.29 Along the way he remarried to Marie-Jeanne Martel.30

He passed away on January 4, 1970, in Montreal. He was still well known enough for a few newspapers to run stories reflecting back on his career. Denis Brodeur, the father of NHL Hall of Famer Martin Brodeur, who himself had a sound athletic career in baseball and hockey before becoming the official photographer of the Montreal Canadiens, remembered playing for Culver:

Mr. Culver was one of my first managers, and together we won the Montreal junior championship. He was respected by all his players. In 1949, he was managing an all-star junior team that was to play a Brooklyn all-star team. I remember the game. Around the 7th inning, we were leading by a run, and a ball was hit between Marcel Durand and I. We let it drop, and the opposing team took advantage to score the tying run. Culver immediately came to see us and said: “Don’t worry, you’ll have other opportunities.” In the 13th inning, Durand hit a double, and I was hitting next. Culver said: “Here’s your chance. Take your time.” I followed with a double and we won 4-3.

“Culver dedicated his whole life to baseball,” concluded Brodeur.31

Postscript

Many questions remain unanswered. While it looks like the contractual dispute with St. Hyacinthe was the main reason for Culver’s departure from the league, one must wonder if there was some pressure from the National Association to get rid of him. The truth might lie between these extremes, with the Montreal management advising Culver to fulfill his contractual obligations with St. Hyacinthe when faced with the prospect of not only an uncertain legal battle with St. Hyacinthe but also the potential difficulties with the National Association.

The other open question is what exactly were the managements of the Montreal team and of the league thinking when they signed Culver? Given the experience of league president Joe Page and the recent presence of the Montreal Royals, they were unlikely to be ignorant of the color line. One possibility is that they believed, maybe with the support of the National Association, that the color line did not extend to an all-Canadian league. But given that Culver was not re-invited for 1923 or 1924, nor were any other black players there nor in other all-Canadian leagues (including the 1940 Provincial League in Quebec) that seems improbable. One can imagine that it would have quickly become untenable for the National Association to allow blacks players in some regions but not others.

In the end, it seems to have taken close to 100 years for the historic significance of Culver’s exploits to be noticed. Even in Quebec where he was a known figure, his pioneering experience in organized baseball was never mentioned. Some of the journalists who covered Jackie Robinson with the Montreal Royals 1946 were surely around 24 years earlier when Culver broke the color line, but nobody seemed to remember. It is not even clear if Culver knew the significance of his presence. It is possible that in its infancy, the Eastern Canada League was not much different from the City league against which it was competing, with the National Association accreditation looking like a marketing gimmick. In fact, the presence of Culver might have been a proof to some that this could not be true, giving an incentive for the league management to let him go to St. Hyacinthe.

In the end, while Culver’s week in Organized Baseball went unnoticed, his long career as a trailblazer helped set the stage for Jackie Robinson’s arrival. But one is left wondering what would have happened if he had not signed that contract with St. Hyacinthe, or if he had been able to get out of it.

CHRISTIAN TRUDEAU is a Professor of Economics at the University of Windsor. For the last 20 years, he has also researched Quebec baseball history, and published in The Hardball Times, the SABR Baseball Research Journal, and in Dominionball: Baseball Above the 49th.

Acknowledgments

I’d like to thank Jodie Calvert and Tina Marie for helping me with the details of Charlie’s life. I’m also grateful to Patrick Carpentier and Alexandre Pratt for assistance on the Montreal baseball scene of the 1920s. Gary Fink and Bill Young also provided helpful comments on early drafts.

Notes

1 “Sherbrooke likely to have pro team”, Sherbrooke Daily Record, April 27, 1921, 10.

2 “L’inauguration le 11 mai”, Le Devoir, April 10, 1922, 7.

3 Charlie Culver was also known as Charlie Calvert. The name, more frequent in the French media, was also taken by his sons. Official documents like voters lists and his obituary used Culver. A 1938 article confirms that Calvert/Culver are one and the same, with Culver being the real name (Le Samedi, 2 juillet 1938, Dans le monde sportif). No reason is provided for the switch, but one reason might be that Culver translates to “butt worm” or “green butt” in French. Victor Power switched to his mother’s maiden name, from Pellot, for similar reasons after playing in the 1949-50 Provincial League.

4 The Seamheads Negro League Encyclopedia.

5 “Les Red Sox Havanais gagnent et perdent ici”, Le Canada, September 29, 1919, 2.

6 “Le Saint-Arsène gagne la plus longue partie de baseball jouée à Montréal”, La Presse, May 24, 1920, 7.

7 Joel Zoss and John Bowman, Diamonds in the Rough: The Untold History of Baseball. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004, 146-149.

8 “Boston viendra ici dimanche”, La Presse, April 26, 1922, 8.

9 “Le Saint-Hyacinthe et Charlie Calvert”, La Presse, April 27, 1922, 8.

10 “On critique l’engagement de Calvert”, La Patrie, May 3, 1922, 6.

11 “On critique l’engagement de Calvert”, La Patrie, May 3, 1922, 6.

12 “Boston défait le club local au Shamrock”, La Presse, May 1, 1922, 14.

13 “Braves victors, 7-2”, Boston Globe, May 1, 1922, 7.

14 “Eugène Grenier contre Calvert”, La Presse, May 4, 1922, 8.

15 “Home runs par Charlie Calvert et Ed. Singher”, La Presse, May 12, 1922, 10, and “Le Montréal défait l’Ottawa”, La Patrie, May 12, 1922, 6. La Presse and La Patrie disagree, with La Patrie crediting Culver with 11 strikeouts.

16 “Valleyfield jouera demain au Shamrock”, La Presse, May 13, 1922, 14.

17 “Premier échec de Montréal après trois succès”, La Patrie, May 15, 1922, 6.

18 “Montreal bat le Valleyfield à Westmount”, La Presse, May 16, 1922, 8.

19 “Home runs par Jos Delisle et Ed. Singher”, La Presse, May 17, 1922, 8.

20 “Belle besogne des frappeurs de Valleyfield ”, La Presse, May 18, 1922, 8.

21 “Le Trois-Rivières prend la tête de la ligue de l’est”, Le Nouvelliste, May 22, 1922, 3.

22 See John Virtue, South of the Color Barrier, McFarland & Co Inc, 2007, 48, and Christian Trudeau, Le baseball à Montréal en 1927, SABR-Québec website archives.

23 An exception is when he signs his 1921 contract. Media coverage mentioned his Negro teams background, and the fact that he only considered playing in Montreal, New York, Philadelphia or Buffalo. See “Le Saint-Henri aura un fameux club cet été“, La Presse, March 26, 1921, 18.

24 Joseph Edwin Cutler appears in the 1900 and 1910 U.S. censuses, with a Charlie born in November 1892 as part of his household. Charlie is listed as son in 1900 but step-son in 1910. Although his color is listed as “white” on both occasions, this is most likely an attempt to hide a potentially scandalous situation. Other evidence that this is the same Charlie Culver is that the WWI registration card lists a Jersey City address, a city where the Joseph Edwin Culver’s family had lived for generations.

25 “United States World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” database with images, FamilySearch, New Jersey > Jersey City no 5; A-H > image 1816 of 4082; citing NARA microfilm publication M1509 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.).

26 Ancestry.com. Quebec, Canada, Vital and Church Records (Drouin Collection), 1621-1968 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2008. Original data: Gabriel Drouin, comp. Drouin Collection. Montreal, Quebec, Canada: Institut Généalogique Drouin.

27 The stories in this paragraph were obtained through an email conversation with Jodie Calvert, grand-daughter of Gérard.

28 For instance, Culver threw at shutout in 1944, at age 52. “Le Saint-Jean gagne à la 11ème manche”, Le Devoir, 12 juin 1944, 9.

29 Voters Lists, Federal Elections, 1935–1980. R1003-6-3-E (RG113-B). Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

30 “Naissances, décès, remerciements, in memoriam”, La Presse, January 5, 1970, 39.

31 “Le Miroir des Sports”, La Presse, January 6, 1970, 24.