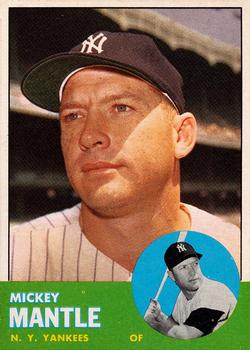

August 4, 1963: Mickey Mantle returns to Yankees in a pinch

Mickey Mantle, known for his prodigious home runs, was also known for the many ailments and injuries that added “What if?” to his legend. Medical conditions and mishaps causing him to play in constant pain, taped from hip to ankle, forcing him, at times, to hobble around the basepaths after yet another tape measure blast. Osteomyelitis, a knee torn up in his second World Series game from stepping in a drainage hole, abscessed hip seeping blood through his uniform, shoulder fallen on in the 1957 World Series, sprains, tears, pulls, and alcoholism. But except for a tiny chip in his right index finger in 1959, not until June 5, 1963, had Mickey Mantle fractured a bone. On that day, he broke his left foot.

Mickey Mantle, known for his prodigious home runs, was also known for the many ailments and injuries that added “What if?” to his legend. Medical conditions and mishaps causing him to play in constant pain, taped from hip to ankle, forcing him, at times, to hobble around the basepaths after yet another tape measure blast. Osteomyelitis, a knee torn up in his second World Series game from stepping in a drainage hole, abscessed hip seeping blood through his uniform, shoulder fallen on in the 1957 World Series, sprains, tears, pulls, and alcoholism. But except for a tiny chip in his right index finger in 1959, not until June 5, 1963, had Mickey Mantle fractured a bone. On that day, he broke his left foot.

Despite all that, until ’63 Mantle had never missed more than 39 games in a season. (That was in 1962 and he still won league MVP.) It wasn’t possible, though, to play through a “slightly oblique fracture of the third metatarsal neck.”1 Mantle missed the next 61 games in a season in which he would play in only 65 games, many as a pinch-hitter. At the time of his injury, he was batting .310 and was tied for third in the league in home runs with 11. He was on pace to hit close to 50.

It was the bottom of the sixth, in Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium, the Orioles behind the Yankees, 3-2. Mantle “set off after a high fly ball hit to deep center field by Brooks Robinson. … He turned … running at full speed in his choppy, high-stepping sprinter’s stride,” Robert Creamer wrote in Sports Illustrated. “… [A]s the ball went over for a home run, Mantle ran into the 7-foot-high wire fence. His left foot hit on the downward stroke of its stride, and his spikes caught in the mesh.”2

On August 4, 1963, the day Mantle returned to the lineup after two months, New York again played Baltimore. This time, it was a home game, second of a doubleheader. The Orioles had slumped, playing their previous 60 games at an even .500 clip, falling to third place behind the first-place Yankees by nine games. Despite not having Mantle in the lineup, New York had amassed a 40-20 record since he broke his foot.

The Yankees played and lost an “uncomplicated … prosaic” first game.3 In the New York Times Will Bradbury wrote that the Yankees “slipped quietly” to defeat, “displayed minimum effort,” and “never really seemed interested.”4

The second game was different, and not just because of Mantle’s return, or that he supplied much of the drama, hitting a pinch-hit game-tying homer in the seventh inning of what became a 10-inning victory. This game was hardly, “prosaic,” or “uncomplicated” … for the wrong reasons. The Yankees, Bradbury wrote, won the game with “a maximum of difficulty. … From the first inning on, it careened along out of control, like a runaway bus.”5

It also had its share of unusual gambits and plays.

Neither starter made it out of the second inning. Indeed, the Orioles starter, promising 20-year-old left-hander Dave McNally, who starting five seasons later put together a string of 22, 20, 24, and 21 wins, lasted only two-thirds of an inning. After getting leadoff hitter Tony Kubek to ground out, two singles, a double, another groundout, and two walks later, McNally headed for a shower he might not have needed.

Yankee starter Jim Bouton didn’t fare much better. In his inning and two-thirds he surrendered two singles, a double, triple, two walks, and — thanks to two errors by Harry Bright — five unearned runs. That year, Bouton had his signature season, going 21-7 with a 2.53 ERA (helped slightly by this outing), and an appearance in the All-Star Game. He also went on to write Ball Four, earning the enmity of virtually all his teammates.6

By the time Mike McCormick took the mound for the bottom of the second, Baltimore retook the lead, 5-4. McCormick had several nice seasons with the Giants, then several mediocre ones with the Orioles and Senators (1963 being one) before returning to San Francisco and winning the Cy Young Award in 1967. This game, he could not find the plate, surrounding four walks and a single and leaving after a third of an inning. The Yankees were back in the lead, 7-5.

Bill Stafford came on and pitched 2⅓ scoreless frames. He also threw one in which he walked three and the Orioles tied the game, 7-7.

In the top of the sixth, after a leadoff triple by Russ Snyder, Steve Hamilton relieved and faced 6-foot-4, 230-pound Boog Powell. The 21-year-old Powell, in his second full season, hit 25 homers. In 1964 he hit 39 and led the league in slugging, He was the 1970 AL MVP, and hit 339 career home runs. This at-bat, he laid down a squeeze bunt and beat Joe Pepitone to the bag. Brooks Robinson homered off Hamilton, the inventor of the “Folly Floater,” which Cleveland’s Tony Horton once fouled out on, and crawled back to the dugout.7

The Orioles retook the lead, 10-7, but Elston Howard hit a two-run blast off future multiteam pitching coach Herm Starrette that cut the lead to 10-9. Hamilton, the future athletic director at his alma mater, Morehead State University, retired the Orioles in order in the seventh, setting the stage for Mantle’s comeback shot.

George Brunet, replacing Starrette for the bottom of the seventh, had a long, decidedly mediocre major-league career, losing 24 more games than he won and twice leading the league in losses. He also, arguably, holds the minor-league record for most career strikeouts, and is a Mexican League Hall of Famer, holding the record for most shutouts south of the border.8 Bouton also mentions him in Ball Four, happy that his Seattle Pilots had gotten Brunet because he was “crazy.” How crazy, Bouton found out later when he asked Brunet why he didn’t wear undershorts. Brunet answered, “Hell, the only time you need them is if you get into a car wreck. Besides, this way I don’t have to worry about losing them.”9

Orioles GM Lee MacPhail was quoted in the Baltimore Sun saying the ovation Mantle received stepping to the plate was “the greatest I’ve ever heard.” Mantle said, “You can’t imagine what a thrill that is. … I was so nervous.… [M]y hands were trembling.”10

Mantle hit other memorable home runs: the “tape measure” blast at Griffith Stadium, the two that hit the façade in Yankee Stadium, the first indoor homer in Houston’s Astrodome, the one that gave Don Larsen all he needed to win his perfect game in the 1956 Series, the one-pitch walk-off in the third game of the 1964 Series.

Yankee pitcher Al Downing said, “Brunet threw one pitch, which Mantle took for a called strike,” then hit the next one, on a line “20 feet off the ground.” Mantle “broke into a cold sweat.” Later, wrote Jane Leavy, he said “he wasn’t sure how he made it around the bases.” The roar of adulation eclipsed the two-minute standing ovation he received when he hobbled to the plate. It got louder and louder as he headed home. The Orioles applauded silently. “Gives you chills standing over there at first base,” Boog Powell said. As Mantle rounded third, Brooks Robinson thought, “That’s why he’s Mickey Mantle.” By the time he reached home plate, “there was tears runnin’ down his face,” added Yankee pitcher Stan Williams.11

In the next morning’s Baltimore Sun, both Mantle and Orioles left fielder Jackie Brandt said they thought a soldier in the stands had interfered with the play. No matter, it was 10-10 and stayed that way until the bottom of the 10th.12

Stu Miller pitched two pristine three-up, three-down innings and started the 10th with a strikeout. Then Tony Kubek singled and Bobby Richardson executed a “reverse run and hit.” When Kubek broke for second, shortstop Luis Aparicio moved to cover the bag, thinking Richardson would go the other way. Richardson hit the ball through the vacated shortstop hole for a single, and Kubek landed on third. An intentional walk to set up a double play or a force at home brought up Elston Howard, bases loaded, one out.

Instead, Yogi Berra came in from coaching first base to pinch-hit for Howard, creating a lefty-righty matchup. Howard had already homered in the game and would go on to win the MVP. This would be Berra’s last year with the Yanks as a player and the first since 1947 that he didn’t make the All-Star squad.

Berra hit a sacrifice fly to score Kubek, and won the game, beating that year’s premier reliever Miller, who led the league in appearances and saves.

It was an exciting return for “The Mick,” made even more interesting because of the kind of crazy game it turned out to be, and the stories behind the players who participated.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted:

Baseball-Reference.com

https://scholarworks.moreheadstate.edu/steve_hamilton_oh/

Mantle, Mickey. with Herb Gluck. The Mick (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1985).

“Mantle’s Heroics Prove Cheers for Slugger Are Well Deserved,” New York Times, August 5, 1963.

White, Gordon S. Jr. “Mantle Fractures Left Foot in Yank Victory at Baltimore,” New York Times, June 6, 1963.

Joseph Wancho, personal correspondence.

Notes

1 Jane Leavy, The Last Boy — Mickey Mantle and the End of America’s Childhood (New York: Harper, 2010), 255. See also Robert W. Creamer, “For the Want of a Warning a Pennant Was Lost,” Sports Illustrated, June 17, 1963: 68-71.

2 See both Leavy and Creamer.

3 Will Bradbury, “Yanks Bow, 7-2, Then Beat Orioles, 11-10, on Berra’s Sacrifice Fly in 10th,” New York Times, August 5, 1963: 22.

4 Bradbury.

5 Bradbury.

6 It has been suggested that few of his teammates actually read the book.

7 See https://thisdayinbaseball.com/tony-horton-crawls-back-to-dugout-after-fouling-out-vs-the-folly-floater/.

8 baseball-reference.com/bullpen/George_Brunet.

9 Jim Bouton, Ball Four 20th Anniversary Edition (New York: Collier Books, 1990), 307.

10 Jim Elliott, “Mantle, Brandt Think Fan Helped on Homer,” Baltimore Sun, August 5, 1963: 15-16.

11 Leavy, 257-8.

12 Elliott.

Additional Stats

New York Yankees 11

Baltimore Orioles 10

10 innings

Yankee Stadium

New York, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.