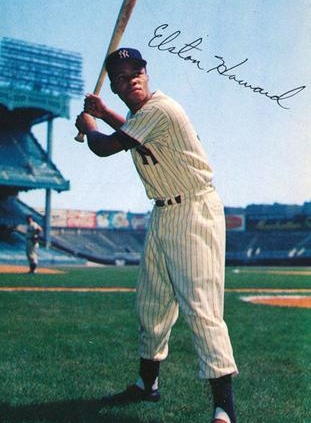

Elston Howard

Elston Howard was born February 23, 1929, in St. Louis, Missouri, the son of Emmaline Webb and Travis Howard. A schoolteacher in Sikeston, Missouri, Emmaline fled to St. Louis when Howard, her principal, refused to marry her. She worked to become a dietician, and when Elston was 5 years old, she married Wayman “Big Poppy” Hill. Elston attended the Toussaint L’Ouverture school as well as the Mt. Zion Baptist Church. The church’s pastor, the Reverend Jeremiah M. Baker, became Elston’s godfather, and the boy was raised to work hard and eat right (thanks to his mother’s dietician’s know-how).

Elston Howard was born February 23, 1929, in St. Louis, Missouri, the son of Emmaline Webb and Travis Howard. A schoolteacher in Sikeston, Missouri, Emmaline fled to St. Louis when Howard, her principal, refused to marry her. She worked to become a dietician, and when Elston was 5 years old, she married Wayman “Big Poppy” Hill. Elston attended the Toussaint L’Ouverture school as well as the Mt. Zion Baptist Church. The church’s pastor, the Reverend Jeremiah M. Baker, became Elston’s godfather, and the boy was raised to work hard and eat right (thanks to his mother’s dietician’s know-how).

In the summer of 1945, Howard, then 16, was playing baseball in a sandlot when Frank Tetnus “Teannie” Edwards approached him. “The biggest kid on the field was hitting the ball so hard and far that it made Teannie mad,” wrote Arlene Howard in her book Elston and Me. “When he got to the field he found out that the big kid was, in fact, one of the youngest on the lot.” Edwards, a former Negro Leagues player himself, helped run the St. Louis Braves and he wanted Elston. Convincing Emmaline was the hardest part. Edwards had to promise that young Elston would eat properly. On Easter Sunday 1946 (April 21), Howard debuted in the Tandy League, catching in a game against Kinloch.1 He had two hits and threw out two runners trying to steal second in a 5-4 loss.

The following year, Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in the Major Leagues. Now 18, Howard was working at Bauer’s grocery store and finishing at all-black Vashon High School. After Robinson’s debut, Vashon hastily formed a baseball team. Elston was already a star athlete at Vashon, playing football, running track, and making all-state in basketball. He was easily the best player in baseball, as well, and after graduating from Vashon, he played another summer with the Braves.

He was urged by Teannie Edwards to attend an open tryout for the St. Louis Cardinals at Sportsman’s Park, but the Cardinals turned a blind eye. (Alas, the Cardinals would not field a black player until 1954 — Tom Alston.) Meanwhile, college beckoned, with three Big Ten schools (Illinois, Michigan and Michigan State) asking for his services in football and several others interested in him for track, basketball, and baseball. Emmaline was hoping her son might grow up to be a doctor. But Edwards called in scouts from the Kansas City Monarchs, the elite Negro Leagues team Jackie Robinson had played for. The Monarchs were so impressed that they went to his mother to negotiate a professional contract. Elston would get $500 a month, mailed directly to her.

In Kansas City, Howard, like the rest of the Monarchs, was treated like a king. Player-manager Buck O’Neil and Earl “Mickey” Taborn, the Monarchs catcher and Ellie’s roommate, showed him the ropes. They enjoyed tailored clothes, terrific food, and the best jazz music in the nation in Kansas City. Because Taborn was the regular catcher, Howard played left field, filling in at first base when O’Neil was out of the lineup. Then in 1949, Taborn left to play for the Triple-A Newark Bears. By the time he returned in 1950, Howard’s new roommate was a young fellow named Ernie Banks.

The players could see what was coming. Monarchs owner Tom Baird had found that there was money to be made selling players to the majors. Ernie and Ellie made a bet: Whoever got to the majors first would call the other and tell him what it was like. Tom Greenwade, the legendary Yankees scout, soon came calling to look at a different player, but Buck O’Neil steered him to Howard. Within days, Elston Howard and Frank Barnes had been sold for $25,000 to the New York Yankees.

Now 21, Howard debuted on July 26, 1950, in left field for the Class A Muskegon, Michigan, Clippers. He would earn $400 a month. The Clippers had a 39-46 record when he arrived, and went 36-18 in the 54 games he played, making the playoffs. Howard batted cleanup and hit well, but the Clippers fell short of the league championship.

Returning to St. Louis for the off-season, Elston announced his decision to marry his high school sweetheart, Delores Williams. Just before the wedding, he was drafted into the Army, at the height of the Korean War. While he was in basic training, the marriage with Delores was dissolved — there are conflicting stories as to why. Howard was sent overseas, but he never fought in Korea. Once the Army realized it had a great baseball player on its hands, he was assigned to Special Services and sent to Japan. That was all Howard ever did in the army: play baseball.

By 1953 Howard was playing for the Yankees’ top farm team, the Kansas City Blues. Another black player, Vic Power from Puerto Rico, was a teammate. Power batted .349 but because of the amount of trouble he stirred up was considered too much of a loose cannon to ever make it in pinstripes. Power was eventually traded to the Philadelphia A’s. In August, Jet magazine featured an article with the headline “Howard May be First Negro With Yankees.”

Shortly before Christmas, Elston proposed to Arlene Henley, whose sister he had gone to high school with. He spent February 1954 at “Yankee Prospects School” with 28 other ballplayers in Lake Wales, Florida, and March at spring training with the big club, sharing a locker room with Yogi Berra, Phil Rizzuto, Mickey Mantle, and Billy Martin. Bill Dickey, former Yankee great, worked with him to make him a major league catcher. Some newspapers, like the Baltimore Afro-American, criticized the Yankees, claiming the move to catcher was a manufactured setback to keep Howard in the minors. When the Yankees broke camp, they took three catchers north with them: Yogi Berra, Charlie Silvera, and Ralph Houk. They didn’t want to send Howard back to the Blues, so they arranged for him to play with the Toronto Maple Leafs in the International League. Canada was a bit more welcoming to black players. Howard won the league MVP Award, hit .330, with 22 homers and 109 RBIs. At the end of the season, he gave Arlene an engagement ring, and they planned to marry in the spring of 1955.

Media reports that Howard would be a Yankee by spring increased, as did protests pressuring the Yankees to integrate. The Yankees won 103 games in 1954, but not the league pennant. Cleveland, featuring black outfielder Larry Doby, won the flag with 111 wins, a sign that the Yankees might need to integrate themselves. The Yankees decided to send Howard to winter ball in Puerto Rico.

The wedding to Arlene was rushed to December 4, 1954. Howard’s godfather, Reverend Baker, married them in Arlene’s mother’s living room. They honeymooned in San Juan, where they lived in the same building as Willie Mays and Sam Jones. Then Howard was off to St. Petersburg for Yankee camp, Arlene back to St. Louis, pregnant with the couple’s first child.

Casey Stengel batted Howard in the cleanup spot much of the spring, prompting Arthur Daley to write in the New York Times, “He seems certain to be the first Negro to make the Yankees. … They’ve waited for one to come along who [is] ‘the Yankee type.’ Elston is a nice, quiet lad whose reserved, gentlemanly demeanor has won him complete acceptance from every Yankee.” Daley was right. Ralph Houk went to the minors, Howard was given his uniform number (32), and on March 21 general manager George Weiss announced that Elston Howard would be coming to New York.

His New York City debut came the Sunday night before the season, when he appeared with Stengel and two other rookies on the Ed Sullivan Show. His on-field debut followed on April 14 at Fenway Park, subbing for Irv Noren, who had been ejected for arguing with an umpire. He got a base hit and knocked in a run. Perhaps the most memorable effect of Howard’s presence on the Yankees that year, though, was that the team changed its hotel policy, staying only in hotels that would accept Howard as a guest. Yogi Berra, Phil Rizzuto, and Hank Bauer were Howard’s best friends on the team. He hit .290 in 97 games his rookie season, with another five hits in the World Series, including a home run in his first World Series at-bat. That performance was offset by eight strikeouts, and the Dodgers won their first World Series. Howard made the final out of the Series, then traveled to Japan with the Yankees for a good will tour.

On the 25-game tour of the Pacific, Howard hit .468 to lead the team. Meanwhile, Elston Jr. was born. Howard’s pay jumped in 1956 from $6,000 to $10,000, he bought a house in St. Louis, and then heard from Stengel that he would be doing more catching. Howard drove the family to Florida, planning to stay overnight with a friend of his godfather’s, a preacher named Martin Luther King. But that night the King house was firebombed and they could not stay there. Almost as disastrous, Howard broke a finger in spring training. Then Norm Siebern went down, and Howard had to fill the gap in the outfield. So much for spending significant time behind the plate. He appeared in only 98 games, 26 at catcher, and finished the year with a so-so .262 batting average, 5 homers, and 34 RBIs. While he had started all seven World Series games in 1955, the team’s acquisition of Enos Slaughter kept Howard on the bench for the first six Series games in 1956. Nonetheless, Stengel started him in Game Seven, and Howard homered and doubled in the 9-0 Yankee win.

The era of change continued to sweep New York. Jackie Robinson retired, and within a year the Giants and Dodgers went west, leaving New York to the Yankees and Elston Howard the only black major leaguer in town. In 1957, he returned to the Yankees once again hoping for more playing time. After Moose Skowron got hurt, Howard played more, and in midseason Stengel named him to the American League All-Star team. He ended the season hitting .253, with 8 home runs and 44 RBIs, still pining for more playing time.

As the 1958 season opened, hope for regular catching duties again flared. Stengel again hinted that Berra could not catch so much. The Howards bought a house in Teaneck, New Jersey. Howard was in left field again on Opening Day in Boston. Daughter Cheryl was bon on May 9, and Howard spent his first game behind the plate that season shortly after that, in the first game of a doubleheader on May 11. At one point Howard’s batting average reached .350, but he would not have enough plate appearances to qualify for the title should his average hold up. Stengel was adamant about platooning his players; Howard ended the year hitting .314, with 11 homers, and 66 RBIs in 103 games, 67 behind the plate.

Elston’s heroism as a Yankee was cemented in the 1958 World Series. Down three games to one in Game Five, Howard got the start in left, despite having dental work that morning. In the sixth, he made a game-saving dive in the outfield, then doubled off the runner, in a play that turned the Series around. “I knew I had to get the ball,” Howard told reporters after the game. “I skinned my knee and my stomach doing it. I’m no outfielder. I’m a catcher, but the manager put me out there and I had to do the best I could.” The next game the Yankees won again, 4-3, in ten innings in which Howard had two hits and scored a run, and in Game Seven, with the score tied 2-2 in the eighth, Howard drove in the go-ahead run. The New York Baseball Writers chapter gave him the Babe Ruth Award as the outstanding player in the World Series.

In 1959, Casey’s annual prediction that Berra would catch less was again wrong. In fact, Yogi caught 116 games, more than the previous year. Though Elston reached his career high in games played, the platoon system made him feel like a part-time player. One thing that did change was that the Yankees picked up another black player, Panamanian Hector Lopez, who came from Kansas City in a trade. But Mickey Mantle was hurt, Whitey Ford’s elbow was balky, and it was all downhill that summer. The Yankees suffered bad losing streaks, including losing five straight at Fenway Park, and finished third in the standings.

Because the club had done poorly, general manager George Weiss tried to cut salaries in 1960. Howard’s offer was $5,000 less than his previous year’s wages, and he held out, missing the reporting date for spring training. Weiss relented, giving him $25,500, a $3,000 raise. Elston, like the rest of the team, had ups and downs that season, but eventually came out on top. Shelved by a few injuries, he nonetheless did get in 107 games, 91 catching, and made the All-Star team. He sprained a finger on the season’s last day. Doctors said he wouldn’t play until Game Three of the World Series, but Casey had him pinch hit in Game One. He hit a two-run home run in the 6-4 loss to Pittsburgh. He had a very good Series until he broke a finger batting against Bob Friend. He batted .462 in the Series, but the Yankees lost, on the famous Bill Mazeroski home run. The loss precipitated the ouster of both manager Casey Stengel and general manager George Weiss.

Ralph Houk, the former second-string catcher pushed back to the minors by Elston’s emergence, became the manager in 1961. Preferring a more stable lineup than Stengel had, Houk plugged Howard in as his catcher 111 times, playing Berra more in left field. New hitting coach Wally Moses encouraged Howard to bat with his feet closer together, allowing him to spray the ball to all fields. Howard responded with a career year, hitting .348 with 21 home runs in 129 games. He again made the All-Star team and would have battled Norm Cash of Detroit for the batting title if he’d had the plate appearances (Cash won it, hitting .361). Between the revitalized Howard, an historic home run race between Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle, and terrific pitching (Ford won 25 games), the Yankees won 109 and took only five games to beat Cincinnati in the World Series. Howard caught all five games and was honored in the off-season as St. Louis’ Man of the Year by the city.

1962 brought another improvement. Pressured to stop segregating their black players in spring training housing, the Yankees moved their camp to Fort Lauderdale. Howard’s pay raise was significant, to $42,500, and he earned it. He hit another 21 home runs with 138 hits and a .279 average in a career-high 136 games. The three catchers, Howard, Berra, and Johnny Blanchard, combined for 44 homers that season. But Howard’s batting average suffered a bit, down to .268 on June 30, though he made the All-Star team again. Most of the homers came in the late-season pennant race with Minnesota, and his and Mantle’s surges insured that the Yankees captured the flag. They faced the San Francisco Giants in a pitching-dominated World Series that was drawn out by rain on both coasts. Elston was behind the plate when Ralph Terry secured the final 1-0 win in Game Seven.

The Howards bought a vacant lot in Teaneck on which to build a larger house. Mayor Matty Feldman begged them not to build in a white neighborhood. The Howards ignored him, and although they suffered graffiti and sabotage during building, they moved in toward the end of the 1963 season. Elston switched to a heavier bat, thirty-eight ounces, that he said helped his power to right field. He hit a career high 28 home runs in 1963, many into the short porch in Yankee Stadium’s right field, and with Mantle and Maris both hobbled by injuries, Howard batted cleanup often that year. He ended the season with a .287 average, and became the first African-American to win the American League MVP Award. He also took home the Gold Glove with his .994 fielding percentage. Howard appeared in his eighth World Series, and he hit .333, but Dodgers’ pitchers Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale kept the Yankees in check. The Dodgers swept in four.

The MVP Award meant off-season banquets and Howard gained ten pounds speaking on the dinner circuit. The award also brought commercial endorsements, and Elston, his wife, and family were featured in ads for oatmeal, mustard, and beer. Howard also became the first black man to ever model clothes for GQ magazine. His salary for 1964 jumped to $60,000, making him one of the best paid players in baseball. (Mantle earned $107,000.) After the season, Ralph Houk moved upstairs to become GM; Yogi Berra became the field manager. Howard told reporters that he had set his sights on the batting title. “It takes planning,” he told them. “That year I hit .348 … I was a base-hit swinger, not a home-run swinger.” He vowed to go with the pitch more and not be too pull-conscious. His efforts were successful. In a career-high 150 games, he tallied a career-high 172 hits for a .313 average, as his homer total dropped to 15. He also walked a career-high 48 times. He did not win the batting title, but did catch all nine innings of the All-Star Game. The Yankees went to the World Series once again, but Bob Gibson’s Cardinals came out on top in seven games.

The loss precipitated major changes. Yogi Berra was fired as manager, replaced by Johnny Keane, and CBS bought the team and did nothing to improve the aging roster. Howard injured his elbow during spring training and it worsened over the next few weeks. By April 13 it was so swollen that he couldn’t bend his arm enough to eat breakfast. Bone chips were surgically removed from his elbow and the Yankees slipped in the standings. Howard didn’t catch again until June 13 and persisted catching 95 games after his return despite the sore arm. He ended with the lowest average of his career, .233, while the Yankees went nowhere. 1966 was not much better. The arm still hurt, the now 37-year-old Howard hit .256, and the Yankees were stuck in the cellar.

Then came 1967. The Yankees offered a $10,000 pay cut. After a four-day holdout, Howard accepted only a $6,000 cut and a clause that if he performed well, he could earn the money back. But on June 26, Rick Monday fouled a ball off Elston’s finger and his hitting suffered. On August 3, Houk telephoned to tell him he had been traded to the Red Sox. Boston was in second place at the time and, unlike the Yankees, had a chance to reach the top. Tom Yawkey called Howard to assure him how much they wanted him. Howard briefly considered retiring, but the chance to play in his tenth World Series was enticing. “If I can help the Red Sox win the pennant this year it would be the greatest thrill of my career,” he told writer Jim Ogle.

He joined the Sox on the road in Minnesota and was greeted by manager Dick Williams, two years his junior. Elston played the next day in a nationally televised contest against the Twins. Not an auspicious beginning: He struck out with the bases loaded in the 2-1 loss. Boston mustered only three hits against Dave Boswell. Elston caught the next day, too, when Boston’s best pitcher, Jim Lonborg, took the hill. But rain cut the game short, and Minnesota won it 2-0 in five innings, as Dean Chance did not allow a base runner and struck out four. They lost again after an off day, at Kansas City, the first time they had lost four games in a row since July 9.

The team sputtered along until August 18, when they beat the Angels 3-2 at Fenway, a game in which Howard caught Gary Bell’s complete game four-hitter. The game would be most remembered, though, for the tragic incident that shattered Tony Conigliaro’s eye socket. Perhaps inspired to win for Tony and helped by Howard’s presence, the Sox reeled off a seven-game win streak, going 14-5 the rest of the month. Eleven of the games were decided by one run. In that span they played five doubleheaders and took three of four in New York. When Howard came to bat against his former team, the Yankee Stadium crowd gave him a standing ovation, one he later called “the best ovation I ever got in my life.”

One of the memorable moments from the stretch run came when the Sox led Minnesota by half a game on August 27. That day the Red Sox faced Chicago, clinging to a 4-3 lead in the ninth. Ken Berry, the tying run at third, attempted to score on a shallow fly caught by right fielder Jose Tartabull. Tartabull’s throw was high, but Elston leaped to snare the ball, then swept the tag down in the same motion — Berry was out and the game was over.

Howard’s greatest contribution to The Impossible Dream, though, may be one that can’t be measured, in his influence on the pitchers and in the clubhouse. His knowledge of the hitters in the league, his game-calling ability, and his calming presence helped the entire pitching staff. “He was like a pitching coach to Lonborg, Gary Bell, Gary Waslewski, Lee Stange, guys like that,” Reggie Smith said. “No doubt Elston helped us win it. We were a young team. Our average age was twenty-six. We needed someone like Ellie to show the way. He brought the Yankee aura of winning to the Red Sox.” The Red Sox, of course, did pull off two amazing wins over Minnesota, while Detroit lost on the final day of the season, giving Boston the pennant.

How fitting that Elston Howard’s tenth and final World Series would be against his old hometown, St. Louis. Unfortunately, the Cardinals beat the Sox; Elston mustered only two hits in the Series. That off-season he pondered retirement, and numerous possibilities. The Red Sox asked him to play and later coach. The Yankees suggested a minor league coaching job or scouting position. Bill Veeck said he wanted to make Howard the game’s first black manager, if he could buy the Washington Senators. In the end, Veeck’s bid to buy the Senators was rebuffed. Howard helped a New Jersey entrepreneur, Frank Hamilton, to market the doughnut — not the edible kind, but the weighted metal ring that batters today use in the on-deck circle. But when spring came, the Red Sox offered a $1,000 raise, And Howard decided to play one more year.

The Red Sox and Elston were banged up. Lonborg broke his leg skiing. Tony Conigliaro did not regain his full eyesight and sat out the season, his career apparently over. George Scott’s average dropped to .171 as his weight rose. Meanwhile, Howard’s elbow acted up again. At midseason, he couldn’t straighten it and he did not want surgery. His playing time limited because of the chronic injury, Howard played in only 71 games. In his final game at Fenway, he received a standing ovation. He had hit .241, with five homers and 18 RBIs. He held a press conference on October 21 to announce his retirement from playing. Then on October 22, he was at another press conference, this one in New York to announce he was taking the first base coaching job with the New York Yankees.

Elston became the first black coach for an American League team but never reached his goal of becoming the first black manager. (Frank Robinson would, in 1975 with the Indians.) While coaching, he took part in various side businesses, including the ongoing involvement with batting doughnuts; a printing company; opening an art gallery with Arlene in Englewood, New Jersey, to sell Haitian and modern art; heading a division of Group Travel, for whom he was the star attraction on corporate tours and cruises; the Elston Howard Sausage Company concession stand at Yankee Stadium; and serving as vice chairman of the board of Home State Bank, an interracially owned bank that catered to the black community. George Steinbrenner, who bought the Yankees in 1973, would not make Howard a manager, but he did make occasional noises about wanting to move Elston from coaching to the front office. Meanwhile, at Yankee Stadium, he became the important counterbalance to the fiery Billy Martin in “The Bronx Zoo.” He coached through the 1978 season.

In mid-February 1979, after nearly collapsing at La Guardia airport, Elston was diagnosed with myocarditis. The muscles of his heart were being attacked by the coxsackie virus and the doctors prescribed total rest. Elston could not participate in spring training. George Steinbrenner told him not to worry. Whenever he recovered, his coaching job would be waiting, and he stayed on the payroll. By August, Howard was still too weak to attend Thurman Munson’s funeral. In February 1980, a year after his attack at the airport, Elston was appointed by Steinbrenner to join the front office staff. He would be an assistant to Steinbrenner, and his duties ranged from appearing at banquets to scouting talent in the Yankees minor league system. His health never recovered, though, and he was often too weak to travel. His heart was giving out, and on December 4, 1980, he was admitted to Columbia Presbyterian Hospital. Two weeks later, he died at age 51. In 1984, the Yankees retired his number 32.

Sources

Howard, Arlene, with Ralph Wimbish. Elston and Me: The Story of the First Black Yankee. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press. 2001.

Retrosheet.org

Baseball-reference.com

The Baseball Library

ProQuest Historical Newspapers

Notes

1 The “Tandy League” was founded in 1922 at Tandy Park in St. Louis and featured teams from local businesses including Union Electric, Scullen Steel, Missouri Pressed Brick, and Mississippi Tanning Company. According to Tweed Webb, it was the oldest “colored men’s league” in St. Louis. [Oral history compiled by Bill Morrison, May 4, 1971, Western Historical Manuscript Collection, University of Missouri-St, Louis]

Full Name

Elston Gene Howard

Born

February 23, 1929 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

Died

December 14, 1980 at New York, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.