September 24, 1919: White Sox clinch AL pennant on Shoeless Joe Jackson walk-off single

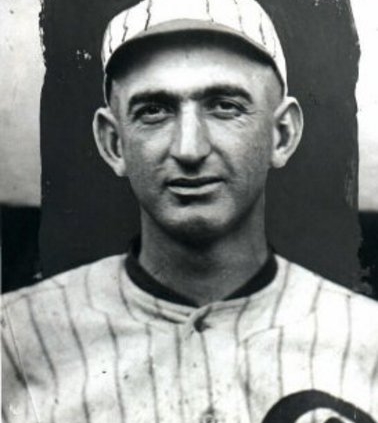

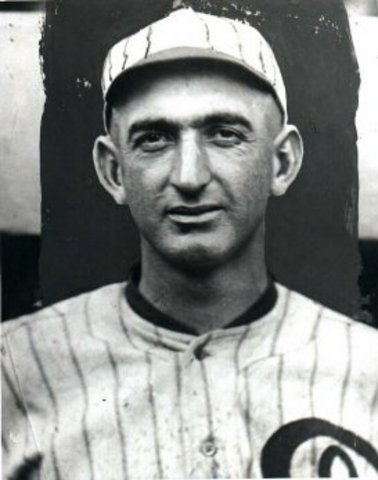

With 29 wins under his belt, Chicago White Sox ace Eddie Cicotte took the mound at Comiskey Park on September 24, 1919, just shy of a milestone victory — and with an opportunity to clinch the American League pennant.

With 29 wins under his belt, Chicago White Sox ace Eddie Cicotte took the mound at Comiskey Park on September 24, 1919, just shy of a milestone victory — and with an opportunity to clinch the American League pennant.

The White Sox’ march to the World Series was taking a little longer than they expected after spending most of the regular season in first place. Except for a brief swoon in late June, the White Sox had cruised comfortably atop the AL standings all year. They had been alone in first place since July 9. But the Cleveland Indians were coming on strong, having won 10 in a row, and Chicago’s eight-game lead was cut in half with just five more to play. A win over the St. Louis Browns, plus a Cleveland loss to the Detroit Tigers, would finally put the pennant in Chicago’s hands.

Chicago manager Kid Gleason called on his veteran right-hander Cicotte for the series opener. “Knuckles” had been on a roll, winning his last six starts and even picking up two wins in relief since his last loss on August 14. He entered this game with a 29-7 record and a 1.69 ERA.

Cicotte was making just his second start since Gleason gave him two weeks off in early September to rest before the World Series. At the time, Cicotte’s break was widely rumored to be because of a sore arm.1 At age 35, Cicotte was closing in on 300 innings for the season. Due to the absence of future Hall of Famer Red Faber, who was suffering from nagging injuries and a lingering bout of influenza, Cicotte and teammate Lefty Williams had been carrying the load for the White Sox. The two pitchers had started, and won, more than half of the team’s games all by themselves.

Later, Cicotte’s long layoff down the stretch would fuel speculation that White Sox owner Charles Comiskey had ordered him benched so he would not reach the 30-win milestone, thereby reneging on a promised $10,000 bonus.2 This slight was seen as the pitcher’s primary motivation for agreeing to help throw the coming World Series, a conspiracy that became known as the Black Sox Scandal.3 But there is no evidence that Comiskey promised that large a bonus to his pitcher4 — and besides, Cicotte did take the mound on September 24 with a chance to win his 30th game. All he had to do was beat the Browns, who came in with a 65-70 record, 22 games behind the first-place White Sox.

St. Louis manager Jimmy Burke sent spitballer Allan Sothoron to the mound. The 26-year-old right-hander was enjoying his finest season, with a 20-11 record and a 2.13 ERA, fourth-best in the American League. He had allowed just one earned run in his last 28⅔ innings against the White Sox.

The Browns jumped on Cicotte early with three runs in the first inning, on RBI singles from Baby Doll Jacobson and Ray Demmitt. Jack Tobin singled home Jacobson for another run in the third to increase the lead to 4-0.

The White Sox countered with two runs in the fifth, when Swede Risberg doubled and scored on a throwing error and Ray Schalk came home on Nemo Leibold’s double to right field. Before Risberg’s at-bat, he asked home-plate umpire George Hildebrand to inspect the baseball. Sothoron’s array of trick pitches had held Chicago to two hits up until that point. The ball was “so badly scarred” that Hildebrand threw it out and the White Sox were able to rally “before [Sothoron] could doctor up another one.”5

The Browns scored again in the seventh, as Jimmy Austin and Jacobson hit back-to-back triples off the struggling Cicotte, who had allowed five earned runs in a start only twice before during the season. Jacobson tried to stretch his hit into a home run, but strong relay throws by center fielder Happy Felsch and shortstop Risberg helped keep the score 5-2 as Cicotte departed for a pinch-hitter. The White Sox starter allowed 11 hits and five runs in his seven innings pitched. As the St. Louis Star reported, the Browns “had little trouble in solving his shoots and they could have gathered more runs … if they had been a little more discreet in running the bases.”6

White Sox team captain Eddie Collins cut the deficit to 5-4 with a one-out triple in the bottom half of the seventh, bringing home Leibold and Eddie Murphy, who had walked in Cicotte’s spot. But Collins was thrown out at the plate on a close play and he argued so vigorously with umpire Hildebrand that he was “banished from the scrap.”7

Long before relief pitchers were considered to be specialists, Dickey Kerr had developed into a bullpen ace for manager Gleason. The rookie left-hander from Texas was often called on in the late innings to hold the opposition until the White Sox’ explosive offense could take over; he recorded a 7-1 record and a 1.78 ERA in 22 relief appearances in 1919.8 On this day, after pitching two scoreless innings in relief of Cicotte, Kerr started the winning rally all by himself.

With the Sox down by one run entering the bottom of the ninth inning, Kerr led off with a single to left field and moved to third on a base hit by Leibold. Fred McMullin, who had come in to replace the ejected Collins, worked Sothoron for a walk to load the bases. Buck Weaver lifted a long sacrifice fly to center field, scoring Kerr and tying the game at 5-5. Leibold advanced to third base after the catch.

Shoeless Joe Jackson stepped to the plate against Sothoron with a chance to win the pennant on one swing of the bat. No American League team had ever clinched a World Series berth with a walk-off victory before.9 Chicago’s star slugger took a “vicious swat” and lined a hit to right-center field that would have gone “for two or three bases under ordinary circumstances.”10 One was all that was needed for Leibold to come home with the winning run. The White Sox mobbed Jackson in celebration and began to look ahead to their World Series matchup with the Cincinnati Reds.

One of the headlines in the Chicago Tribune sports section the following day offered an ominous preview of what was to come: “Bookies Favor Sox.”11

Sources

Box scores for this game can be found at Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org:

baseball-reference.com/boxes/CHA/CHA191909240.shtml.

retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1919/B09240CHA1919.htm.

Quinn, John M. “Lefty Kerr Stars Against Brownies as Sox Land Flag,” St. Louis Star, September 25, 1919.

Sanborn, I.E. “White Sox Crown Themselves American League Champs,” Chicago Tribune, September 25, 1919: 23.

Sanborn, I.E. “Cicotte Routed in Clash That Nails Flag For Sox, 6-5,” Chicago Tribune, September 25, 1919: 23.

Wray, John E. “Cicotte’s Weakness Alarms White Sox Supporters; Hard Hitting Clinches Pennant,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 25, 1919: 31.

Notes

1 “Kerr Will Outdo Cicotte Against Reds, Fan Wagers,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 20, 1919: 8.

2 Bob Hoie, “1919 Baseball Salaries and the Mythically Underpaid Chicago White Sox,” Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game. (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Spring 2012): 29-30. Hoie explains the genesis and evolution of the “Cicotte bonus” story, which began with a December 1919 report in Collyer’s Eye and was embellished by Eliot Asinof in Eight Men Out. In 1990 Rob Neyer began dismantling the myth in Bill James’s The Baseball Book, and other writers have followed with even more evidence to disprove the theory. See, for example, David Marasco, “Cicotte’s 29 Wins in 1919,” The Diamond Angle, accessed online at https://thediamondangle.com/marasco/hist/cicotte.html on December 3, 2006; and Lowell D. Blaisdell, “Legends as an Expression of Baseball Memory,” Journal of Sport History 19 (Winter 1992).

3 Regardless of the reasons for Cicotte’s long layoff, just about everyone involved agreed that his involvement in the plot to fix the World Series had already begun before then. Cicotte himself testified that the fix was first discussed at a meeting of the players on September 10 or 12 at the Ansonia Hotel in New York. He returned to the field to win his 29th game on September 19 against the Boston Red Sox and then faced the Browns five days later. See William F. Lamb, Black Sox in the Courtroom: The Grand Jury, Criminal Trial, and Civil Litigation (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2013): 49-51.

4 Hoie, op. cit. As Hoie writes, “The amount of the ($10,000) bonus and its structure were … highly improbable.” Contract cards acquired at the turn of the 21st century by the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library show that Cicotte was one of the highest-paid players in baseball, making a total of $8,000 in 1919 — second highest among all pitchers in the American League to Walter Johnson. Comiskey did promise a much smaller bonus to Lefty Williams in 1919: $375 for winning 15 games and an additional $500 if he won 20, both of which he earned. It seems extremely unlikely that Comiskey would have promised such a large bonus to Cicotte — more than his annual salary — for a similar performance milestone.

5 I.E. Sanborn, “Cicotte Routed in Clash That Nails Flag for Sox, 6-5,” Chicago Tribune, September 25, 1919: 23.

6 John M. Quinn, “Lefty Kerr Stars Against Brownies as Sox Land Flag,” St. Louis Star, September 25, 1919: 16.

7 Sanborn, op. cit.

8 Dickey Kerr 1919 season splits, Baseball-Reference.com, accessed online at baseball-reference.com/players/split.fcgi?id=kerrdi01&year=1919&t=p on January 13, 2018.

9 After Jackson’s winning hit, no other AL team would clinch a pennant on a walk-off victory for a quarter-century. A full list of all 20 walk-off pennant clinchers in the World Series era can be found in the author’s article, “Walking Off to the World Series,” at The National Pastime Museum.

10 Sanborn, op. cit.

11 “Bookies Favor Sox,” Chicago Tribune, September 25, 1919: 23.

Additional Stats

Chicago White Sox 5

St. Louis Browns 4

Comiskey Park

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.