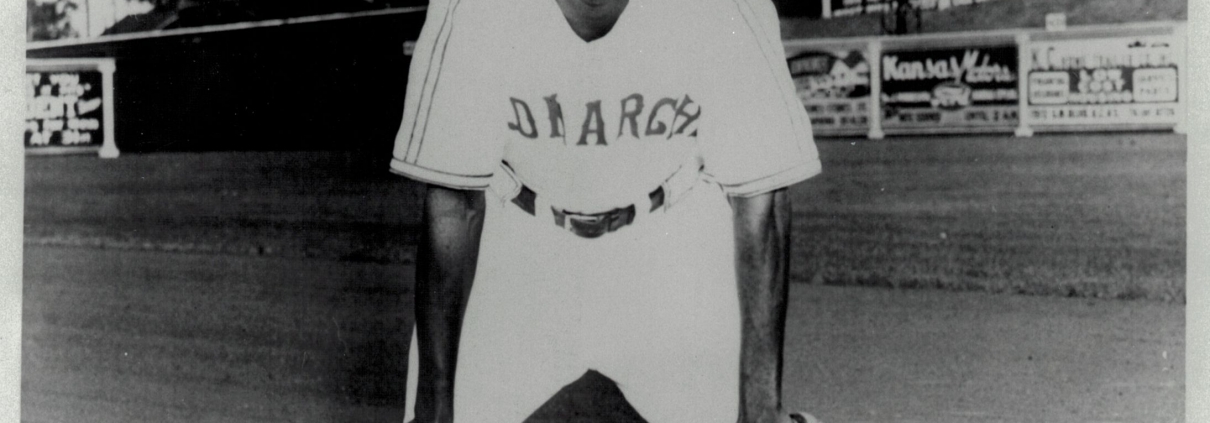

Bonnie Serrell

During World War II, the Kansas City Monarchs had two middle infielders who hit for average, exhibited extra-base power, and played defense with flair. Born in the winter of 1919, Jackie Robinson not only changed baseball history but altered US history as well. Born in the winter of 1920, Bonnie Serrell toiled in a far dimmer spotlight but played an impactful role on one of the best teams in the storied history of the Monarchs. Although a year younger than Robinson, Serrell preceded him as a Kansas City middle infielder.

During World War II, the Kansas City Monarchs had two middle infielders who hit for average, exhibited extra-base power, and played defense with flair. Born in the winter of 1919, Jackie Robinson not only changed baseball history but altered US history as well. Born in the winter of 1920, Bonnie Serrell toiled in a far dimmer spotlight but played an impactful role on one of the best teams in the storied history of the Monarchs. Although a year younger than Robinson, Serrell preceded him as a Kansas City middle infielder.

Born in Natchez, Louisiana, on March 9, 1920, Barney Clinton Serrell went by many names. Better known in baseball circles as Bonnie, Serrell also went by Barney Clinton Hoskins, taking on the surname of his maternal grandparents, Will and Mattie Hoskins.1 Bonnie’s mother, Piccola, married Frank Serrell in Upshur, Texas, on August 6, 1925. According to his World War I draft registration card, Frank, born on February 26, 1896, came from Gilmer, Texas, in Upshur County. At the time of the 1930 census, Piccola, Bonnie, and his two brothers (Leon, born in 1922, and James, born in 1924) lived with the widowed Mattie Hoskins.2

Like many contemporaries, Serrell sought to make himself appear younger, and many sources list his birthdate as 1922, suggesting that he took on his brother Leon’s birth year as his own. The 1940 Census reported an expansion in the family that now included Bonnie’s siblings Margaret (born in 1933), Thomas Jr. (1938), and Donald (1940).

Bonnie’s father had gone north in search of improved employed possibilities. “In 1933,” a biographical dictionary wrote, “the family was reunited in Chicago … [Bonnie] Serrell left high school before graduation and developed his baseball skills on Chicago’s sandlots.”3 Having attracted the attention of the American Giants, Serrell made his professional debut with a one-game cup of coffee in left field for Chicago in 1941.

After this modest debut, Serrell went from spare part to star with Kansas City in 1942. One preview overlooked Serrell entirely, excluding him from a list of 15 Monarchs and suggesting that Newt Allen would play second base.4 Subsequent data reveal that the underrated Serrell represented a major offensive force in the Negro American League for his first three full seasons. The chart below, which draws from data on Seamheads.com, lists his top 10 finishes in several NAL offensive categories:

|

Season |

Runs |

Hits |

2B |

3B |

HR |

RBI |

BA |

OBP |

SLG |

OPS |

|

1942 |

T-3 |

3 |

1 |

5 |

4 |

2 |

3 |

T-2 |

3 |

|

|

1943 |

T-2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

T-2 |

6 |

9 |

|||

|

1944 |

T-1 |

2 |

T-3 |

T-2 |

T-1 |

1 |

5 |

7 |

5 |

5 |

Hardly an accumulator of empty statistics, Serrell had multiple meaningful hits during the magical run by the Monarchs in 1942. Getting revenge against his former team, the Chicago American Giants, Serrell on June 28 singled in Buck O’Neil from second base in the top of the 13th inning with the go-ahead run and then scored an insurance tally as Kansas City won 9-7. On July 5 Serrell hit two homers, likely the only multiple-homer game of his Negro League career,5 as the Monarchs beat the Birmingham Black Barons 11-5 in the opener of a doubleheader. On July 7 Serrell tripled in the 10th off Memphis Red Sox ace Verdell Mathis in a game started by Satchel Paige that turned into a classic pitching duel at Pelican Stadium in New Orleans. Serrell did not score, and Kansas City lost 1-0.6 On August 24 before a record crowd exceeding 2,400 at City Stadium in St. Joseph, Missouri, the Monarchs mauled the American Giants 10-4 thanks in part to Serrell, who “hit a long homer over the right field wall (and) also did some neat work at second.”7

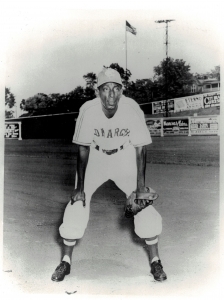

This debut would have appeared impressive for a one-dimensional slugger in the prime of his career, but Serrell stands out even more given that he combined these offensive outbursts as a 22-year-old rookie with a slick defensive skillset that earned him the nickname of the Vacuum Cleaner for his defensive flashiness. Kansas City teammate Connie Johnson recalled, “He played fancy, but that’s the only way he could play. He wasn’t clownin’ but he’d get the ball and throw it over his shoulder and behind him and all like that and make the double play.”8

While predominantly a second baseman, Serrell played at least once at every position except pitcher and catcher. On April 19, 1942, in right field, he made a game-saving catch to rob Birmingham’s Goose Tatum of a walk-off homer in a game that Kansas City held on to win, 8-6.

As the youngest player to appear in the 1942 Negro League World Series, Serrell exceeded his strong regular-season numbers with a superlative slash line of .412/.412/.588 in the Monarchs’ sweep of the NNL champion Homestead Grays.

Both Serrell and the Monarchs played well in 1943, but they were unable to match the success of the 1942 championship campaign. The Birmingham Black Barons were the first-half champions of the NAL, while the Chicago American Giants captured the second-half title; although the Monarchs had a better composite record than both teams, Kansas City failed to make the playoffs in 1943. Serrell, though still a strong player compared to league norms, regressed offensively in 1943 with his on-base percentage dropping from .403 to .325 and his slugging percentage falling from .565 to .421.

The fortunes of Serrell and the Monarchs diverged in 1944. While Kansas City faded to fourth, Serrell surged with a season similar to his first with the Monarchs by batting .364 (he had hit .366 in 1942) with a career-high on-base percentage of .407. The high point of Serrell’s season occurred at Comiskey Park in Chicago, where he had played as an amateur and now returned to triumphantly as a professional on the most prominent stage of the Negro Leagues. There, Serrell took part in his only East-West All-Star Game. Batting sixth and playing the whole contest, he went 2-for-3 with a run and an RBI as the West rallied for a 7-4 win.

In 1945 Serrell played just four games for Kansas City before traveling to Mexico for the summer and to Cuba for the winter. As a result, Bill James later wrote, “the Monarchs signed Jackie Robinson, who was three years older than Serrell and not considered to be as good a player.”9 Serrell played in the Mexican League from 1945 to 1948, spending the first three seasons with Tampico and splitting the 1948 campaign between San Luis Potosi and Veracruz. He also plied his trade for the Marianao team of the Cuban Winter League for two consecutive seasons. During his first campaign in Cuba, the 1945-46 season, he led the league with 14 doubles.10

Hilton Smith, the Monarchs’ Hall of Fame pitcher, believed that Serrell should have been the player to break the color barrier rather than Jackie Robinson. According to Smith, “Jackie couldn’t touch that boy. He could do everything. It just killed him when they picked Jackie and not him. He left, went to Mexico and never came back.”11 Smith was not entirely correct about Serrell never coming back until after Bonnie received what he had hoped was a legitimate opportunity to make it to the major leagues. As Robinson went on to greater glory in Montreal and Brooklyn, Serrell returned to Kansas City for three more seasons, 1949 to 1951. In 1951, as the Monarchs were bleeding money, the team sold Serrell to the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League for $1,000; the Seals were the Triple-A franchise of the New York Yankees.12

Lefty O’Doul managed the Seals when the 31-year-old Serrell joined the team in 1951. Serrell asserted that O’Doul discriminated against Blacks, saying: “What should have been the highlight of my career became a disaster. The source of my problem was the Seals’ manager Lefty O’Doul. … Lefty was a racist and didn’t try to hide his feelings.” After meeting Serrell for the first time and watching him practice with teammate Bob Thurman, O’Doul, according to Serrell, loudly declared to team management, “I told you to get ballplayers, not monkeys!”13

Playing on the same team with a National League star of the future in Lew Burdette and an American League star of the past in Joe Page, Serrell, perhaps unsurprisingly given the attitude of his manager, struggled with a .243/.273/.320 slash line. The Seals likewise sputtered to a last-place record of 74-93.

After his unpleasant experiences in San Francisco, Serrell never played professional baseball for a U.S.-based team again. Returning to Mexico, he spent 1952 to 1956 with the Nuevo Laredo team and split his last season as a player south of the border between Nuevo Laredo and Monterrey. Although Serrell never had received the fair shot at making the major leagues that he had wanted so badly, he still merited occasional mentions in his home country, thanks to the back pages of The Sporting News, which showed that he ranked among the top five hitters in both summer and winter Mexican leagues,14 and retained his talent for the clutch hit.15 Serrell could still swing a sweet stick as he batted .370 in the Mexican League in 1952 and .376 for the Arizona-Mexico League in his swan song season of 1958.16 In 10 seasons in Mexico, Serrell had a robust .311 batting average with 162-game equivalencies of 206 hits, 105 runs, and 12 triples.17

Serrell lived nearly 40 years after his playing career ended and had two tough stints as manager that left him with a record of 100-130 as a skipper. After managing Juarez in the Arizona-Mexican League in 1958, he “managed the San Luis Potosi Indians for part of the 1963 Mexican Center League season. Serrell married a woman from Mexico and settled there after his playing career ended.”18 He died in East Palo Alto, California, on August 15, 1996.

While Serrell never kept company with Robinson in the big leagues, he did have a longer baseball career and outlived his more famous teammate by nearly a quarter of a century. Robinson rightly deserves the everlasting gratitude of all baseball fans for permanently smashing the color line. Serrell deserves respect for both his more modest but still impressive accomplishments as a Negro League star and the choice he made to play a significant portion of his career in Mexico, which provided a much less racist environment than the United States. This latter decision clearly freed him from having to carry the enormous burdens assumed by Robinson and likely led Serrell to enjoy a more peaceful existence.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Seamheads.com.

Notes

1 Because Serrell sometimes used Hoskins as his last name, he may also have taken on William as his first name to match his grandfather.

2 Thanks to Rick Bush for his extensive genealogical research that provided much of the information for this paragraph and helped to flesh out Serrell’s family background.

3 David L. Porter, ed., Biographical Dictionary of American Sports: Baseball Revised and Expanded Edition Q-Z (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000), 1387.

4 “Baseball Notes,” The Afro American, April 21, 1942: 12. Serrell would play 29 games at second for Kansas City in 1942. Allen had just nine appearances at that position.

5 Of the five seasons with statistics for Serrell in the Seamheads Negro Leagues database, Serrell has just two multi-homer seasons (3 in 1942 and 2 in 1944. See seamheads.com/NegroLgs/player.php?playerID=serre01bon (accessed October 8, 2020).

6 Frederick C. Bush, “Verdell Mathis,” sabr.org/bioproj/person/verdell-mathis/ (accessed September 15, 2020).

7 “Record Stadium Crowd Watches Monarchs Win,” St. Joseph (Missouri) Gazette, August 25, 1942: 5.

8 Scott Simkus, “Strat-O-Matic Negro League All-Stars Guide Book,” 2009.

9 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: The Free Press, 2001), 184. Like others, James erroneously saw Serrell as having a birth year of 1922 rather than 1920.

10 “William (Bonnie) Serrell Record in Cuba,” Ashland Collection clipping in the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s file on Serrell. Thanks to Reference Librarian Cassidy Lent for scanning the Serrell file.

11 Janet Bruce, The Kansas City Monarchs: Champions of Black Baseball (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1985), 113.

12 William A. Young, J.L. Wilkinson and the Kansas City Monarchs (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2016), 175.

13 Amy Essington, The Integration of the Pacific Coast League (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2018), 98.

14 “Toppers in Mexican Coast,” The Sporting News, January 26, 1955: 23; “Mexican Averages,” The Sporting News, September 5, 1956: 35.

15 “[T]he Tomateros won a 16-inning thriller, 6 to 5, when Barney Serrell singled home the clincher.” See A.O. Camou, “Obregon Sweeps Four Tilts; Ramirez’ Zero Skein Halted,” The Sporting News, November 30, 1955: 34.

16 Dick Clark and Larry Lester, eds., The Negro Leagues Book (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1994), 301.

17 Pedro Treto Cisneros, The Mexican League: Comprehensive Player Statistics, 1937-2001 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2011), 253. The author calculated the full-season averages using data from this book.

18 “Barney Serrell,” baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Barney_Serrell (accessed September 15, 2020). He worked as a laborer according to Porter, 1388.

Full Name

Barney Clinton Serrell

Born

March 9, 1920 at Natchez, LA (USA)

Died

August 1, 1996 at Santa Clara, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.