Baseball Umpires in 1921

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in 2021 as part of the SABR Century 1921 Project.

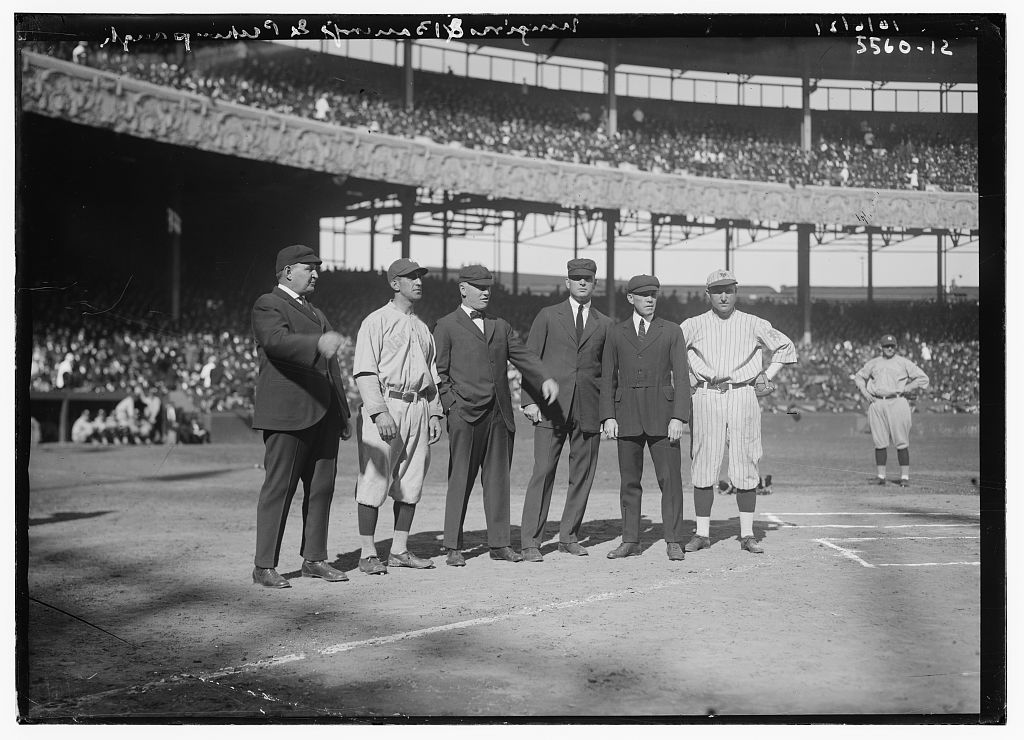

New York Yankees captain Roger Peckinpaugh, second from left, and New York Giants captain Dave Bancroft, far right, pose with the umpires at home plate before Game One of the 1921 World Series at the Polo Grounds in New York. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, BAIN NEWS SERVICE)

The 2020 Umpire Media Guide contains a section entitled “Historical Timeline of Major League Umpiring.” The only item from the 1920s in the timeline informs readers that “Umpires in both leagues began the practice of rubbing mud into the balls prior to each game in order to remove the gloss.”1

The Media Guide was, of course, printed before Major League Baseball determined in December 2020 that a number of additional leagues — for instance, the Negro National League, founded in 1920 — were of major-league status.

Our goal here is to look at the 1921 season and learn a bit about umpires and umpiring during that season.

It would be nice to learn a little more about the introduction of rubbing mud into baseballs, but what else happened in 1921? Looking through the pages of The Sporting News, one finds quite a number of interesting bits of information and anecdotes, both from major-league baseball and the minor leagues.

There were incidents involving Ty Cobb getting into a bloody fight with umpire Billy Evans under the grandstand, a player getting spiked by Pacific Coast League umpire Ted McGrew, and future Hall of Fame umpire Bill Klem having his leg fractured by a pitch thrown by none other than Carl Mays. Not all the stories were bloody, of course. Cobb himself suggested that baseball teams might consider using umpires as scouts. There was a report from a winter league game that said an umpire got impatient in a scoreless extra-inning game, asked for the bat, and hit a single to win the game for one of the teams. There were some major-league umpires who first debuted as such in 1921.

Throughout the year, the “Questions and Answers” column offered information about umpire decisions. For instance, in the July 7 issue, someone from Ransom, Kansas, posed this question: “Runner on first starts for second; pitch is fourth ball on which batter goes to first; runner going to second over-ran that base, catcher throws ball to second and runner is tagged out, but umpire says he is safe. Was decision correct?” The answer supplied was: “The runner was entitled to second base and no more; the ball was in play and passing the base constituted an attempt to advance; runner is out and umpire is wrong.”2

Let’s take a spin through the pages of the weekly “Bible of Baseball” and see some of the stories that relate to umpires and umpiring.

Interestingly, one of the first articles that appears relates to pace of play. It wasn’t the only mention of this concern. In the Questions and Answers column, a reader from St. Louis wrote: “Batter takes his swing at pitched ball, then steps out of box and pitcher puts over another pitch. Do different leagues have different rules as to whether the pitch should be called on the batter?” Answer: “There is no difference in rules, but one umpire may be more lenient than another. The batter is supposed to be up there and in his box, unless for good reason he is out and the umpire has suspended play for him. It is not his privilege to step out and delay the game just to suit his own humor.”3

Before the season got under way, the newspaper printed a lengthy article entitled “Umpires Get Fresh Orders to ‘Keep Game Moving.’” The article quoted veteran American League umpire Billy Evans (he umpired from 1906 through 1927) at length. Evans was featured in many issues of The Sporting News, both before and after the season.

Several games in 1921 featured more than two umpires. Most of the games worked used two-man crews (home and first base). The American League used three-man crews (home, first base, and third base) on a number of occasions, much more frequently than did the National League.

This was a change from 1920, where there were very few games (seven in the American League but only one date in the National League) that had more than two men umpire a game. The one NL date was July 18, which actually saw four umpires work a game in Cincinnati.

There was also a game in 1921 — just one — when a four-man crew was used: May 8 at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn. In that one game, there was a second-base umpire. The crew was Bill Brennan (home); Bob Emslie (first base); Barry McCormick (second base); and Bob Hart (third base). A look at contemporary newspapers did not discern mention of why this was the case.

In the NL, the Brooklyn Robins game featured a three-man crew in both halves of the July 4 doubleheader. The two Cincinnati Reds games on September 18 had a three-man crew. The Giants had three-man crews on July 6 and on July 7. There were five Cardinals games with a three-man crew, and three Pirates games, but never once was there a Phillies game with more than the standard two-man crew.

In the AL, the Yankees had 36 games worked by a three-man crew, the Indians had 23, the Philadelphia Athletics 20, Washington Senators 19, Detroit Tigers 17, Boston Red Sox 16, but the Chicago White Sox only 4.4

National League umpires in 1921:

- Bill Brennan — worked 143 games, 98 of them at home plate and 45 at first base

- Bob Emslie — 107 games (one at home plate and 105 at first base. He worked one game at 3B)

- Bob Hart — 152 games (80 HP, 69 1B, 4 at 3B)

- Bill Klem — 108 games (78, 28, 2)

- Barry McCormick — 158 games (72, 84, 1 at second base and 1 at third base)

- Charlie Moran — 144 games (73, 71, 0)

- Hank O’Day — 125 games (56, 65, 4)

- Ernie Quigley — 142 games (76, 66, 0)

- Cy Rigler — 147 games (72, 74, 1)

There were two umpires who filled in some NL games:

- Ducky Holmes — worked 13 games in 1921

- Charles McCafferty — worked 5 games in 1921

As we can see, McCormick worked four more games than any NL team played in the 154-game schedule.

Negro National League

On the very last day of 1921, the Chicago Defender published an article by Negro National League President Andrew “Rube” Foster defending his practice of having employed only White umpires.5 The umpires hired were not league employees — not a full-time staff. The first hiring of NNL staff umpires did not come until 1923.6

The umpires hired were local men and that may have presented its own problems. Dink Mothell, who had played portions of the 1920 season with the Chicago American Giants and Kansas City Monarchs, recalled those days years later: “Our umpiring was about the poorest you’d ever want to see. When we went to Chicago, they had white semi-pro umpires. But the majority of our umpires, they always wanted to give the home club the best. We had one umpire in Chicago, Boone. If you said something about a strike, the next time, even if it was in the dirt or over your head, he’d call it a strike.”7

Foster was responding to a degree of pressure he had come under, reflected in articles including “Demand for Umpires of Color Is Growing Among the Fans,” which appeared in the October 9, 1920, Chicago Defender.8 The Defender questioned: “Why do eighteen men playing the game of baseball have to have one or two white men to umpire?” The paper noted, “It would be utterly impossible for one or two gentlemen of color to undertake to go over and umpire the White Sox game.” Regarding the quality of the “the two regular white umpires behind the plate,” the Defender said, “A high school boy could do as good at times and at other times far better.”9

Foster acknowledged that he had received “hundreds of letters from the people” complaining that he “did not give our people the privilege of umpiring.” He outlined his reasons and said he looked ahead to the day that he could hire Black umpires for league work; “I would have them in preference to white umpires, but I cannot allow my preference to run away with my business judgment.”10

As spring training ended for the Chicago American Giants and the team headed north from Palm Beach, Florida, the Defender declared that the question of umpires had not been determined yet for 1921 but that “thousands of fans at the park were crying for an umpire of the Race, especially on bases.”11

Ed Goeckel was the regular umpire at Schorling Park. He had earlier umpired in the Federal League, working the full 1914 season, but had not been rehired for 1915.

American League umpires in 1921:

- Ollie Chill — 153 games (72 at HP, 69 at 1B, 12 at 3B)

- Tommy Connolly — 160 games (73, 72, 15)

- Bill Dinneen –143 games (64, 68, 11)

- Billy Evans — 151 games (74, 70, 7)

- George Hildebrand — 152 games (66, 69, 17)

- George Moriarty — 156 games (72, 78, 6)

- Dick Nallin –154 games (56, 59, 39)

- Brick Owens — 147 games (72, 70, 5)

- Frank Wilson — 161 games (67, 61, 33)

This was Wilson’s first year as a major-league umpire. He worked seven more games than in the 154-game schedule. Connolly and Moriarty both worked more games than any given team played.

Among the 20 umpires who worked in the major leagues in 1921, some were former ballplayers and some were not. Some were veteran major-league umpires and some were relatively new. There are only 10 umpires who have been inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Four of them served in 1921: Tommy Connolly, Billy Evans, Bill Klem, and Hank O’Day.

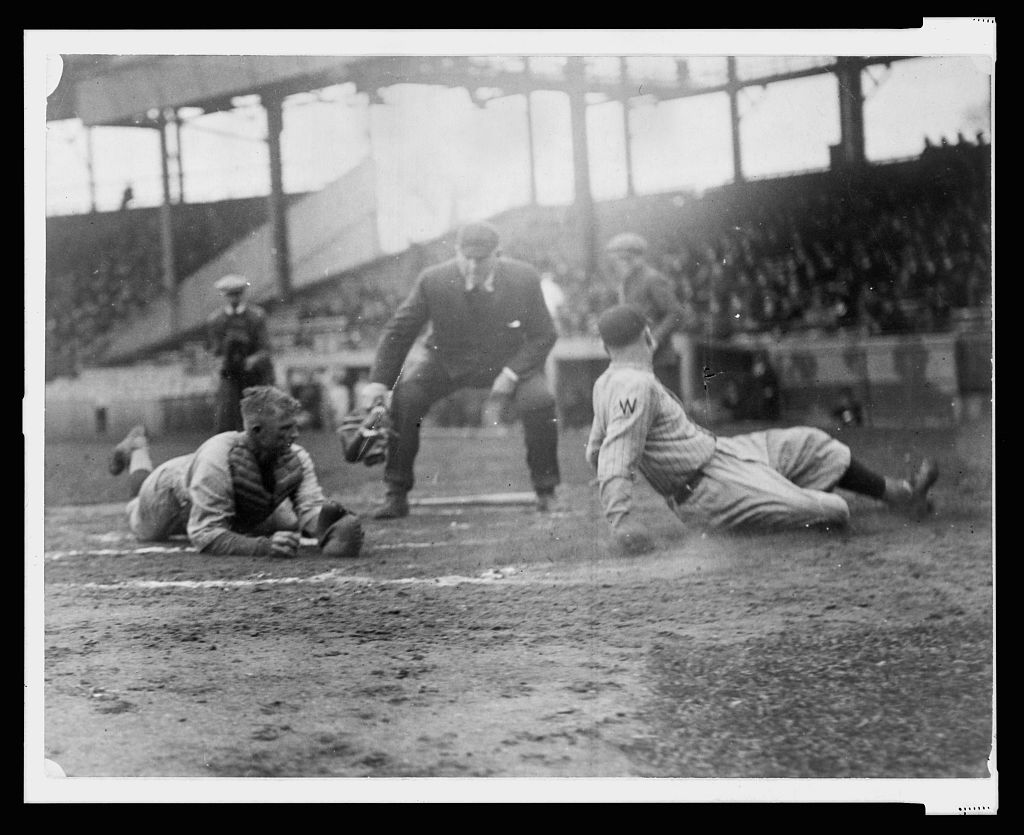

Washington’s Joe Judge slides across home plate and awaits the umpire’s call in an undated game from 1921. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

A few other notes regarding the umpires

National League

Bill Brennan had started umpiring in 1909, working 22 games. From 1910 to 1913, he worked a full NL schedule, but in 1914 and 1915 worked in the Federal League. After that league folded, he worked in the minors for a few years but was hired by the NL for 1921. From 1922 until his death in 1933, he returned to the Southern League, where he served as umpire in chief.12

Bob Emslie had been a pitcher and occasional outfielder back in 1883-85. He started umpiring in the American Association in 1890 and served as a NL umpire from 1891 through 1921, umpiring a few games in each of the years 1922-24.

Bob Hart was an American League umpire in 1912 and 1913, returning to the majors as a NL umpire from 1920 through 1929.

Bill Klem worked as a National League umpire from 1905 into 1941, working a total of 5,375 major-league games. He was voted into the Hall of Fame in 1953, inducted with Tommy Connolly that year as the first umpires to be so honored. Klem ejected 346 players during his tenure.

Barry McCormick played in 613 National League and 376 American League games from 1895 through 1904, primarily as an infielder. His first two years umpiring were for the Federal League in 1914 and 1915. He joined the AL in 1917 and then worked in the NL from 1919 through 1929.

Charlie Moran played for the Cardinals as a pitcher and shortstop in four 1903 games, then as a catcher in 16 games in 1905. He was a National League umpire from 1918 through 1939, and a standout college football coach.

Hank O’Day played in 232 big-league games, mostly as a pitcher (73-110) from 1884 to 1890. Even while a player, he had been asked to fill in as an umpire on occasion. In 1895 he worked in 75 NL games, becoming a regular in 1897 and then working through 1937. With Tommy Connolly, he worked the first World Series in the modern era, in 1903. He is the most recent umpire named to the Hall of Fame, in 2013.

Ernie Quigley — a native of New Brunswick — umpired 3,354 NL games from his start in mid-1913 through a handful of games in 1937 and 1938.

Cy Rigler worked 4,142 games in the majors from four games at the end of 1906 through a full 1935 season. He worked 10 World Series, and worked in the very first All-Star Game, held in 1933.

Ducky Holmes played in nine games at the start of the Cardinals’ 1906 season. He worked 13 National League games in 1921. In 1923 and 1924 he worked full seasons in the American League, in 294 games over the two seasons.

Charles McCafferty worked five games in 1921, all in Chicago, and then in three other games in 1923, two in Chicago and one in St. Louis.

American League

Ollie Chill worked as an AL umpire from 1914 through 1922, missing from July 19 through September 11 in the latter year.

Tommy Connolly. Like Ernie Quigley, Connolly was born outside the United States — in Connolly’s case, in Manchester, England. He and Bill Klem were the first two umpires named to the Hall of Fame, in 1953. Connolly worked in the National League from 1898 through 1900, then served as an American League umpire from its first year in 1901 through 1931, and one game in 1933. He worked the first modern World Series with Hank O’Day in 1903, and the first games played at both Fenway Park and Yankee Stadium.

Bill Dinneen started his career with the 1898 Washington Nationals. He pitched for the Boston Beaneaters in 1900 and 1901, then switched to Boston’s American League team and in 1903 had his third of four 20-win seasons, and then was a three-game winner in the 1903 World Series. He finished his pitching career with the 1909 St. Louis Browns. The last month of that season, he umpired 20 AL games, then worked steadily through the 1937 season.

Billy Evans umpired in the American League from 1906 through 1927, never working fewer than 126 games. He often wrote about baseball and umpiring, and had a nationally syndicated column. He is a member of the Baseball Hall of Fame.

George Hildebrand played outfield in 11 games for the 1902 Brooklyn Superbas. He played for a number of West Coast teams and umpired in the Pacific Coast League from 1901 through 1912, before becoming an American League umpire in 1913. For 22 years (through 1934) he worked in 3,331 AL games.

George Moriarty was an infielder and sometimes outfielder who played in 1,070 games from 1903 to 1916, all but five of them in the American League. He umpired in almost three times as many games, from 1917 through 1940 — that tenure bizarrely interrupted by a stint managing the Detroit Tigers for two years in the middle of this stretch (1927 and 1928).

Dick Nallin worked without interruption as an AL umpire from 1915 to 1932. Among those he ejected from games were Buck Weaver, Branch Rickey, Ty Cobb, and Clark Griffith — and those were just the first four.

Brick Owens umpired in the National League for parts of 1908, 1912, and 1913. After two years in the American Association, he moved to the American League and worked games from 1916 through 1937.

Frank Wilson’s first year in the majors was with the American League in 1921. He had worked in the International League in 1919 and in the Western League in 1920. He worked 161 games in 1921, then partial seasons in 1922 and 1923, before putting in full years in 1923 through 1927. Appendicitis struck him after 45 games in 1928; he died of an operation in June, nine days after his final game.

The 1921 season as it unfolded

Now let us return to the year 1921 and see the sorts of things The Sporting News reported about umpires during that season.

One headline that captures attention was entitled “Would Have Players Do All the Umpiring” in the January 13 issue. J.W. “Doc” Seabough of the Class-D Western Association’s Springfield (Missouri) Midgets ballclub “sprung on his fellow magnates a proposition that they do away with regular umpires the coming season and instead use players as officials.”13 The idea didn’t spring from nowhere; it was reported that in some 50 Western Association games in 1920, players had indeed had to substitute for umpires and they had performed quite well. His other arguments included:

- Active players have better eyesight than veteran players (who were often the pool from which umpires were drawn).

- Active players are more agile than the “has-beens.”

- Players are less inclined to “ride” player-umpires.

- “Player-umpires seldom show as much favoritism for their own club as the average veteran umpire does for the home team.”

- By eliminating transportation expenses for the professional umpires, the lower minors could afford to use the “double umpire” (two-man crew) system.

- By being able to offer additional pay to the players (particularly pitchers), clubs could acquire better players.

At first the other owners scoffed, but his points generated enough interest that he was requested to write up a proposal. Among the counter-arguments were that the player-umpires who had filled in had done so only occasionally and were thus accorded leeway and courtesy by their erstwhile teammates. This would not endure over the course of regular umpiring, and in particular when it came to discipline, the whole thing would become impracticable.

In the same issue, readers were told something that would never happen in today’s baseball — Bill Brennan was going to join the New York Giants in San Antonio and umpire every one of their spring training games.14 Brennan was officially hired as a NL umpire in early April. Somewhat strangely, given the heightened awareness of all in the wake of the Black Sox Scandal, it is remarkable that Brennan, when not employed as an umpire, was “connected with the race track at New Orleans.”15

The issue of January 20 announced the hiring of Frank Wilson to officiate American League games.16

The January 27 Sporting News contained an article by William B. Hanna headlined “It Cost 10 Cents to Cuss an Umpire in the Early Days.”17 It looked back on some of the differences between the “Massachusetts game” and the “New York game.” A book of rules and regulations published by the Putnam Baseball Club of Brooklyn included a section on “Fines and Penalties” that could be assessed against players. Among them were fines of 10 cents, levied:

- “For using improper or profane language at any meeting or during the progress of any game”;

- “For disputing the decision of an umpire during field exercise”;

- “For audibly expressing his opinion on a doubtful play before the decision of an umpire is given, except when called upon him to do so. …”

Damon Runyon offered a number of ruminations about baseball in the February 3 issue. He was writing the story of “a ball player who sees his finish.” In the story, the ball player says at one point, “I might become an umpire. I have often thought I could make good handling an indicator and an umpire gets good money. Many big league umpires began as ball players, and several were pitchers. Hank O’Day, of the National League, was a hurler way back in the long ago. Bill Dineen [sic], of the American League, was another pitcher. I was watching Dineen working as an umpire in a World’s Series one time, and it occurred to me that he was a striking example of how soon fans forget a man.”18

Ty Cobb offered a suggestion. Rather than employing baseball scouts to “wander all over the earth, eating up money for railroad fare looking at players,” perhaps it would be better for a club to “have a representative in each of a number of selected leagues … an umpire … would be fine.”19

The Western Association kicked off 1921 by taking another tack. The president of the league fired all the umpires. He’d been dissatisfied with the staff’s work in 1920, so he canned the lot of them, hiring new men, each of whom was said to have six or more years of experience in Organized Baseball.20

One experienced umpire, who worked farther west, was the Pacific Coast League’s Lord Byron. He’d been a National League umpire from 1913 through 1919, but was dropped from the NL and had taken a position with the Coast League in 1920. The Sporting News said he’d been invited back to the NL but chose instead to stay in the PCL (where he worked through the 1924 season). William J. “Lord” Byron was known for his “peculiarities, one of which was to sing ditties of his own composition to the players as the games were played.”21

As spring training progressed, a couple of incidents made the paper. The National League’s Bill Brennan, as noted above, was “traveling with the Giants as their umpire.” Washington Senators manager George McBride got into a dispute with Brennan during a game in Jackson, Tennessee … and when he “refused to leave the field,” Brennan forfeited the game to the Giants.22 At a game in Mobile a few days earlier, the Giants’ Cozy Dolan had been “arrested and fined for hitting Ed Lauzon, a local umpire.”23

Two articles dealt with attempts to cleanse the game of too much association with gambling. The state legislature in Washington passed a “baseball bribery act,” which — among other things, declared that “umpires, who, in connection with their official duties, shall commit a wilful act with the intent to cause a baseball club to win or lose a game which otherwise would not have been won or lost under the rules of play governing the game, shall be guilty of a misdemeanor.”24

Before each season began, American League President Ban Johnson convened the league’s umpires in Chicago. This year, the paper wrote, “he wants to put the umpires on the job of keeping an eagle eye open to the existence of gambling. Also, he is going to insist upon the umpires killing off all delays in play.”25 He planned to have representatives of the league at every game, and after the games to be “present where players congregate.” He was aware, he let it be known, that some managers were thought to “delegate their stars to do the kicking to the umpires, knowing that if the indicator man chases the star there will be a lot of protests from the fans.” He expressed determination to look into this and discipline all involved should it occur.26

Bill Brennan brooked no bluster in reestablishing himself as a National League umpire. On April 19, when the Giants played their first game at Boston’s Braves Field, he ejected Braves catcher Mickey O’Neil in the sixth inning for arguing balls and strikes. The very next day, he threw out Braves manager Fred Mitchell for the same thing.

Elected to the Hall of Fame in 1953, Bill Klem is credited with helping upgrade dignity and respect for umpiring during a major-league career that spanned 37 years from 1905 to 1941. (TRADING CARD DATABASE)

One umpire who was missing in the early going was Bill Klem. During a spring-training game between the New York Yankees and Brooklyn Robins at Atlanta on April 5, the veteran ump (he had 16 years with the NL under his belt) was struck by a ball, causing an “incomplete fracture of the shin bone.” Who was pitching at the time? Carl Mays. The Yankees pitcher had, of course, been the one whose pitch had struck and killed Ray Chapman on August 16, 1920 — less than eight months earlier. But — lest anyone jump to conclusions — the ball that broke Klem’s left shin bone during the fourth inning was a foul off the bat of Brooklyn’s catcher Otto Miller, who was attempting a sacrifice at the time.27 Klem had to be carried off the field; George Moriarty put on the gear and took over working the plate. The first game Klem was able to work in the 1921 season was May 28, and — not 100 percent ready — he had to defer a second game to June 11, after which he worked steadily for the rest of the year.

Charlie Moran was dubbed the “Monte Christo of Football World” in a May 5 article. The NL umpire had enjoyed tremendous success coaching football at Centre College of Danville, Kentucky, netting him a number of offers from “several of the big institutions of the country.”28 Before he’d taken up umpiring, he had been head coach at Texas A&M (and is in their Hall of Fame). It was anticipated he would retire from umpiring, but in fact he kept on through the 1937 season. He was still able to continue coaching, and worked at Bucknell from 1924 to 1926, among other positions.

Would rosin bags come to be permitted? A Sporting News editorial in late May suggested it might not be a bad idea. Though there were rules against “any foreign substance” being employed by pitchers, the National League proposed considering permitting “pitchers afflicted with palm perspiration to use a bit of rosin to dry their moist hands.” The amount and use of rosin for this purpose would be regulated by the umpires, who would carry “a small bag” of it and dole it out as deemed advisable.29

Without comment, we will present in full the text of one brief article: “A fine row broke out in the Russellville-Sheffield game [in the Alabama-Tennessee League]. On May 25. Carl Newton, manager of the Russellville’s team, alleged Umpire Clark was drunk and, angered at the way he was handling things, beat him up. Clark forfeited the game to Sheffield and then ducked. Newton was ‘barred from the league’ by the president. Gordon Cowie, for attacking the umpire, but the league head decided to summons Clark and make him tell the circumstances of the row, which may result in Newton being reinstated.”30 Final disposition of the matter was apparently not reported.

In another one of those stories that looked back a few years, Jim Bluejacket had once been fined $10 by Western League umpire Joe Becker for being in “high spirits” due to imbibing too much before the game. He pulled some antics, drawing the fine. The next day he came in to pitch again and Becker demanded that the fine be paid. Bluejacket asked for a receipt. He was asked why. “Because, Umpire, I die some day and when I get to gate of Heaven, St. Peter ask me, ‘Was you honest? Did you pay all your debts? Did you pay that umpire ten dollars?’ Then if I got no receipt I maybe have to go chasing all over hell to find you, Mr. Umpire, to prove I pay all debts.” He got his receipt.31

On May 28 at Pittsburgh, there was a game that home-plate umpire Bill Brennan voided during the eighth inning, when one of the visiting Reds was called out on a play after Reds pitcher Dolf Luque threw the ball on the ground in anger after a call at the plate went against him. The ball rolled to the dugout, where it was picked up by a player and tossed back on the field, picked up and used to tag out batter Clyde Barnhart (because Brennan had not seen the ineligible player touch the ball). The Pirates protested the game and it was resumed on June 30, with umpires Bob Emslie and Bill Klem.32

Umpire Frank Wilson was deemed to be “handicapped by being short of height.”33 In a June 8 game at the Polo Grounds, the Indians were ahead, 3-2, after 8½ innings. They had lost the previous four games. In the bottom of the ninth, with one out and a runner on first, Frank “Home Run” Baker swung at two pitches, then “took a swing clear around on the third one and started for the bench. To the surprise of everyone, including Baker, the umpire called a ball and Baker came back.”34 He singled, and soon scored the winning run. Cleveland manager Tris Speaker argued that Baker had struck out and appealed to Wilson to consult first-base umpire George Hildebrand. Wilson refused, and threatened to eject Speaker, who protested the game. Powers wrote that “many other clubs” had questioned Wilson’s judgment.

The league upheld the protest of the May 28 game, league President John Heydler accepting that even though neither umpire had seen the ball handled improperly, many others had and provided affidavits to that effect, among them many spectators at the game. “It has always been customary in the past to allow matters to stand when the arbiters testified that they did not see the play.”35 Correspondent Davis called the precedent “a poor one” which permitted incompetent umpiring. Heydler was prepared to accept the “word of reputable witnesses,” seen as perhaps setting a new precedent. It wasn’t undercutting the league’s umpires, the reporter asserted, so much as it was recognizing that “umpires are not infallible, and that their mistakes should be rectified wherever possible.”36 Heydler himself had umpired 83 National League games in 1895-98.

As a reward for being a good boy, AL umpire Billy Evans was given a week off to go to Canada. Evans had been active for a number of years in an “industrial welfare association” in Cleveland. Every summer for the previous five years, the group had held an annual outing in the Canadian lake country. Because Ban Johnson had an extra umpire in Frank Wilson, he surprised Evans — who had been umpiring since 1906 — by encouraging him to take the week off.37

Sent to the hoosegow? Texas League umpire Paul Sentell traded punches with Wichita Falls acting manager Arch Tanner. Sentell ordered Tanner to leave the ballpark and Tanner refused, whereupon fisticuffs broke out once more. Police took Tanner “to the lockup and after the game Sentell also was escorted to the hoosegow.”38 Sentell was promoted to the majors the next year; he worked in 153 NL games in 1922, and four more in 1923.

It was umpire Ted McGrew’s misfortune to be positioned near the third-base bag when Sam Crawford of the Los Angeles Angels came barreling in; the two collided and Crawford “had one of his fingers badly gashed.”39 It was declared a case of umpire spiking baserunner.

Apparently the Tigers’ Harry Heilman became so incensed during an exhibition game in Saginaw, Michigan, that he hit the umpire with a bat. A Detroit Times writer explained that major leaguers don’t like to lose exhibition games because of the embarrassment but that sometimes it would be “better if the majors accepted poor umpiring without comment.”40

A brief bit in an October issue reported that the South Atlantic League’s Steamboat Johnson was the only umpire in the league to work the entire season and that he had been retained for 1922 as well.41 Johnson had previously worked 66 games in the National League back in 1914.

A riot during the Junior World’s Series? The Louisville Colonels of the International League beat the American Association’s Baltimore Orioles in the 1921 matchup between the two league champions, five games to three. Bill McGowan umpired 4,425 American League games from 1925 through 1954. In 1921 he was working in the International League. The other umpire in the World Series was Connolly of the AA.

Game Four in Louisville was on Sunday, October 9, and it was forfeited to Baltimore, 9-0. First, there was a call in the seventh inning that angered the locals. “It was the much-misunderstood ‘infield fly’ rule that started the riot,” a later press report proclaimed.42 Fans stormed onto the field and it took about 15 minutes to restore order. Emotions boiled over in top of the ninth inning. With Baltimore baserunners on, two outs, and a 3-and-2 count, McGowan called the next pitch a ball. The crowd thought Merwin Jacobson had swung at it and missed. That loaded the bases and a single scored two runs.

The next batter was called safe on a very close play at first base and “the crowd apparently did not stop to consider that it was not McGowan who made the decision and the spectators charged on the field, hurling cushions as they rushed forward toward the umpire [McGowan at the plate, not Connolly at first base.]” Louisville manager Joe McCarthy helped get the umpires into the office while a fracas ensued. Some 5,300 fans “pelted the police and umpires with cushions.” No one was hurt and no arrests were made, but “the police used their clubs freely.”43 After order was restored and the streets cleared, the umpires emerged from the office.

Then there was a time that readers were told an umpire had decided to bat during a game. It was the aforementioned Texas League umpire Paul Sentell, a former ballplayer himself and no longer in the hoosegow, during a winter league game in Destrehan, Louisiana, about 20 miles from New Orleans. Both teams had played 10 innings of ball without a run being scored. The pitching was superb and showed no sign of weakening. In the 11th inning, though, the Mex-Pets team of Destrehan got a baserunner to third base. “What does Sentell do, but shed his mask, grab the bat, go in there himself, and swat a single off Bill Bailey, driving over the run and winning the game — or at least putting an end to it.” Sentell then “bowed to the applauding crowd, gather[ed] up his mask and pad” and hustled home “to his delayed dinner.”44

A nice story, but that’s not the way it was reported in the New Orleans newspapers. The Times-Picayune said that Sentell had been coaching and pinch-hit — a whole different thing. It was the first game of the Dixie Winter League season, and the Mex-Pets had beaten the Pathe Red Roosters, “a crack team of professionals from the big teams.”45

As has been mentioned, there was already some nostalgia regarding early baseball. Birmingham, Alabama, had been founded in 1871. After the 1921 baseball season was over, a significant number of major leaguers made their way to the warmer weather of the South — players including Shufflin’ Phil Douglas, Whitey Glazer, and Dixie Walker — a dozen or more. To help celebrate the 50th anniversary of Birmingham, they played a vintage baseball game by 1871 rules. The catcher stood far behind the plate. A batted ball caught on one bounce was an out. Commissioner Kenesaw M. Landis granted Douglas (who had won two games for the New York Giants in the 1921 World Series) dispensation to umpire the game. The Sporting News didn’t report a final score or much in the way of detail, but did allow that “unlike a lot of exhibition games they played real baseball.”46

There was, of course, winter baseball in California, too. Ty Cobb managed San Francisco and during a November 19 game in Vernon got into it with umpire Billy Phyle. Cobb was thrown out of the game, refused to leave, and Phyle finally forfeited the game to Vernon. Frank Chance, head of the California Winter League, fined Cobb $150 — $50 for abusive language and $100 for causing the game to be forfeit.47

There was the light side, too, of course, and a column about the 1880s Western League umpire Abner Moreland offered a number of entertaining reminiscences, including a mention of a fellow umpire named Donahue “who clowned it so persistently throughout each game that he kept the fans laughing, but his antics delayed the games considerably. Donahue would always run with the runner, slide when the player slid, then come up with a spectacular flourish amid the dust.”48

Donahue would then “withhold his decision while he regained his feet and then carefully brush off his uniform and dust his cap, with comedy gestures, forcing the fans to wait until he was good and ready. Then he made his way leisurely to the front of the grandstand, where he would announce in great detail his decision, carefully choosing his words. For instance, he would describe his run and slide from home plate to first base, or from first to second base, and would declare the runner to be out, loudly telling all within earshot that this was due to the fact that the ball beat the runner to the bag and was momentarily held there or that the second baseman or shortstop had brought the ball into contact with the runner’s person while the runner was yet three inches, or whatever the approximate distance might be, from the bag.”49

Ty Cobb engaged in a discussion about umpires with the Oakland Enquirer. He praised those who had a “judicial attitude,” but added that “some of our well-known umpires act as if they were on the wrong side of the bench.” He praised some by name for calling them as they saw them, acknowledging that one can make a mistake, but declaimed those who he believed were “homers” (cowed by the home crowd), called plays before the play was resolved, or were too hasty in threatening to throw out someone who complained about a call. He was sensitive on the subject of ejections. Baseball was something of a battle, he said, and players are on edge. It wasn’t good for an aggressive umpire to react too precipitously to a player’s protest (“Men under the strain of a contest should not and cannot be handled in that manner.”) He added, “The umpires have taken the fight out of baseball.”50

Commissioner Landis ruled that umpires are humans.51 He reinstated Western League umpire Bill Guthrie on November 29. Guthrie had been struck by a bottle thrown at him by a fan in Tulsa. A man in a soldier’s uniform was pointed to as the perpetrator. About 20 minutes after the game, umpire and soldier encountered each other and Guthrie decked the soldier. It turned out the soldier was disabled. Guthrie was suspended indefinitely, but Landis reinstated him, saying that an umpire was “human” and not obliged to take physical and verbal assaults without responding.52

As the year came to its end, former pitcher Big Ed Walsh was told by Ban Johnson that he could have a position umpiring in the American League. Walsh worked 87 games in 1922, through July 22. In the National League, John Heydler announced the hiring of Cy Pfirman. Pfirman worked through the 1936 season. Both announcements were noted in the January 5, 1922, Sporting News. An article in the January 12 issue noted that Walsh had no prior umpiring experience, his value as an umpire necessarily thus being of “unknown quality.” It granted that very capable and well-regarded umpires such as Bill Dinneen and George Moriarty had moved from being players to arbiters without any form of apprenticeship, but felt for those umpires who had worked their way up to the “highest class of minor league baseball.” They had their ambitions.

Likewise, players have to prove their worth. Having “pull” shouldn’t grant one to right to leapfrog others. Walsh, author L.H. Addington argued, should put in some time in the minor leagues and work his way up.53 Why had Walsh’s season ended after July 22? Perhaps his biography for SABR provides a hint. Walsh hated the job, mainly because he did not like calling strikes. “I remember when I wanted every pitch to be a strike,” he said.54

BILL NOWLIN still lives in the same Cambridge, Massachusetts, house he was in when he joined SABR in the last century. He’s been active both in the Boston Chapter and nationally, a member of the Board of Directors since 2004 (a good year for Red Sox fans). He has written several hundred bios and game accounts, and helped edit a good number of SABR’s books.

Notes

1 “Historical Timeline of Major League Umpiring,” The 2020 Umpire Media Guide (Major League Baseball, 2020), 82.

2 “Questions and Answers,” The Sporting News, July 7, 1921: 4.

3 “Questions and Answers,” The Sporting News, January 13, 1921: 4.

4 Thanks to Tom Ruane of Retrosheet for providing data regarding crew assignments.

5 Rube Foster, “Future of Race Umpires Depends on Men of Today,” Chicago Defender, December 31, 1921: 10.

6 In 1923, the league hired its first staff umpires, in lieu of continuing to contract with local White umpires. The NNL hired six Black staff umpires. including Billy Donaldson, Bert Gholston, and Caesar Johnson. See “‘Brown Skin’ Umpires,” Chicago Defender, May 12, 1923: 12, and Tom Johnson, “Baseball: Spectators — Players — Umpires,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 25, 1923: 7.

7 John Holway, Black Ball Tales (Springfield, Virginia: Scorpio Books, 2008), 63.

8 “Demand for Umpires of Color Is Growing Among the Fans,” Chicago Defender, October 9, 1920: 6.

9 “Demand for Umpires of Color Is Growing Among the Fans.”

10 Foster, “Future of Race Umpires Depends on Men of Today.”

11 “Rube Foster’s Bunch Bound for Chicago,” Chicago Defender, April 9,1921: 10.

12 See David W. Anderson’s “Bill Brennan” for why he left the NL again after 1921. https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/bill-brennan/

13 “Would Have Players Do All the Umpiring,” The Sporting News, January 13, 1921: 8.

14 E.V. O’Connor, “He Fixes Everything but the Weather Man,” The Sporting News, January 13, 1921: 3.

15 “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, April 14, 1921: 6.

16 “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, January 20, 1921: 6.

17 William B. Hanna, “It Cost 10 Cents to Cuss an Umpire in the Early Days,” The Sporting News, January 27, 1921: 6.

18 Damon Runyon, “On the Road to Hasbeenville,” The Sporting News, February 3, 1921: 6.

19 “Ty Has Ideas on Scouting,” The Sporting News, February 24, 1921: 5.

20 “Letcher’s League in Shape for Good Year,” The Sporting News, February 24, 1921: 8.

21 “Singing Umpire Sticks to Coast,” The Sporting News, March 10, 1921: 4. For a couple of articles on the “singing umpire,” see Brendan Macgranachan, “Singing Bill,” Seamheads.com, February 20, 2009, at https://seamheads.com/blog/2009/02/20/singing-bill/, and Michael Clair, “Bill Byron, the ‘singing umpire,’ once thought a player’s insult was so original, he didn’t eject him,” Cut4 by MLB.com, February 4, 2017, at https://www.mlb.com/cut4/bill-byron-didn-t-eject-a-player-because-his-insult-was-so-unique-c215199776.

22 The game was, of course, not a championship game, and the purpose of the game — to get players in shape for the coming season — was lost for the day. See “Here Is Some Fine Stuff,” The Sporting News, April 7, 1921: 1.

23 “Here Is Some Fine Stuff.”

24 “Blankenship Breaks Spokane’s Last Link,” The Sporting News, April 7, 1921: 2.

25 W.A. Phelon, “Johnson’s Umpires to Help in Cleanup,” The Sporting News, April 7, 1921: 2.

26 W.A. Phelon.

27 “Brooklyn Captures Free-Hitting Game,” New York Times, April 6, 1921: 24.

28 “He’s Monte Christo of Football World,” The Sporting News, May 5, 1921: 4.

29 “A Bit of Rosin on Demand,” The Sporting News, May 26, 1921: 4.

30 “Ugly Row in T.-A. League,” The Sporting News, June 2, 1921: 3.

31 “Baseball By-Plays,” The Sporting News, June 2, 1921: 4.

32 See the complicated account. Ralph S. Davis, “Pittsburg Keeps Balance in Crisis,” The Sporting News, June 9, 1921: 3.

33 F.J. Powers, “Runs of Defeats for Champions Gets on Tris Speaker’s Nerves,” The Sporting News, June 16, 1921: 1.

34 F.J. Powers.

35 Ralph S. Davis, “Umpirical Word Not Final with Heydler,” The Sporting News, June 30, 1921: 3.

36 Ralph S. Davis.

37 “As a Reward for Being a Good Boy,” The Sporting News, June 30, 1921: 4.

38 “Texas League,” The Sporting News, July 14, 1921: 6.

39 “Pacific Coast League,” The Sporting News, August 11, 1921: 6.

40 “Scribbled by Scribes,” The Sporting News, September 8, 1921: 4.

41 “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, October 13, 1921: 4.

42 “Junior World’s Series,” The Sporting News, October 20, 1921: 8.

43 “Junior World’s Series,” The Sporting News, October 13, 1921: 6. That the game was forfeited likely didn’t change what would have been the outcome. The Orioles led 9-4 heading into the ninth.

44 “Paul Would Have His Joke,” The Sporting News, November 3, 1921: 6.

45 “Paul Sentell in Comeback to Win Game,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, October 24, 1921: 10.

46 Leonard Wise, “Birmingham Boys Glad to Be at Home,” The Sporting News, November 17, 1921: 2.

47 “Ty’s Temperament Brings Him Penalty,” The Sporting News, November 24, 1921: 1.

48 Guy L. Ralston, “Veteran of Early Days Can Relate Stories of Umpiring,” The Sporting News, November 24, 1921: 5.

49 Guy L. Ralston.

50 “Ty Cobb Gives Ideas of Umpire’s Duties,” The Sporting News, December 8, 1921: 7.

51 Alexander F. Jones, “Landis Rules Umpires Are Humans,” Atlanta Constitution, December 5, 1921: 4.

52 “The Rule of Reason in Case of Bill Guthrie,” The Sporting News, December 8, 1921: 7.

53 L.H. Addington, “If Players, Then Why Not Umpires?,” The Sporting News, January 12, 1922: 6.

54 “Walsh hated the job, mainly because he did not like calling strikes. ‘I remember when I wanted every pitch to be a strike,’ he said.” See Stuart Schimler, “Big Ed Walsh,” in Bill Nowlin and Emmet R. Nowlin, eds., 20-Game Losers (Phoenix: SABR, 2017), 413, quoting “Big Ed Walsh, Former Oneonta Baseball Manager, Dies at 78,” Oneonta Star, May 27, 1959: 12.