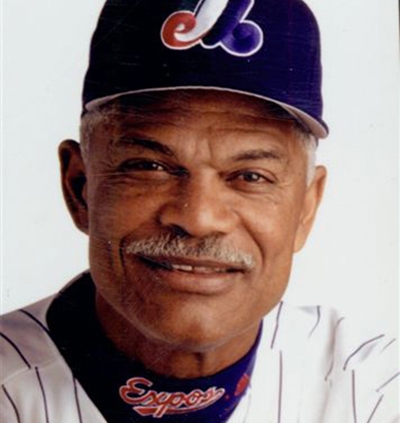

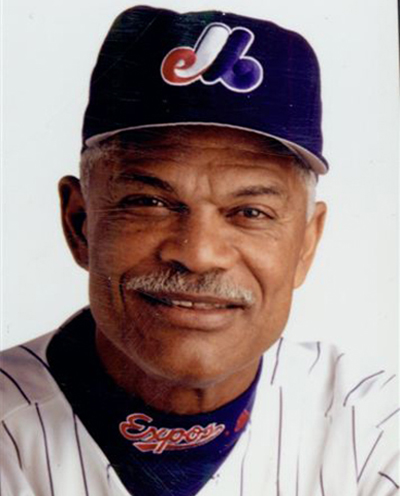

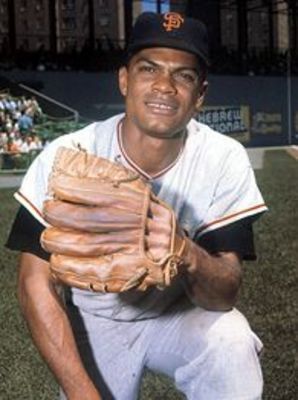

Felipe Alou

This article was written by Mark Armour

This article was published in Spring 2013 Baseball Research Journal

Upon arriving in the United States in the spring of 1956, without knowing a single person, ignorant of the native language, customs, and food, and unaware of racism, Felipe Alou was armed with nothing but his mind, courage, determination, and talent. No Dominican had ever played in the major leagues, and there were as yet only a handful of dark-skinned Latinos playing in the US. Over the course of the next five decades, Alou would become and remain one of the most respected figures in baseball, an All-Star player, a team leader, and a successful manager. While he was admired throughout baseball, among his fellow Dominican players—who would soon be plentiful—he was a revered hero.

“Felipe was really the first,” remembered Manny Mota, “the guy who cleared the way. He was an inspiration to everybody [in the Dominican Republic]. He was a good example.”1 Juan Marichal, like Mota a fellow Dominican, agreed. “Everybody respects Felipe Alou,” he recalled. “He was the leader of most of the Latin players.”2 Willie Mays, a teammate of all of these players, remembered, “It was like a family when they came over.”3 These men helped define the baseball of their time, and Alou was both a leader and a friend to many of them.

Felipe Rojas Alou was born on May 12, 1935 in Bajos de Haina, San Cristóbal, on the southern coast of the Dominican Republic, a few miles from Santo Domingo. (His nickname at home is El Panqué [Sweet Bread] de Haina.) The first child born to José Rojas and Virginia Alou, he was followed by María, Mateo, Jesús, Juan, and Virginia. José also had two children with a previous wife who had died young. Though José was dark-skinned and Virginia (descending from Spaniards) was white, Felipe did not give this much thought—race was not a big issue in his country.

José Rojas was a carpenter and blacksmith who built their small four-room house and many of the other houses in the vicinity. The Rojas family had very little money, so they were often at the mercy of their neighbors’ ability to pay their bills. World War II brought further hardship, causing José to turn to fishing to feed his family. Although they did not always have food, their well-built home afforded them shelter that not everyone in their neighborhood had.4 Felipe swam in the nearby ocean, and was an avid fisherman—a hobby he kept up the rest of his life.

In keeping with the Latin custom, this man is known in full as Felipe Rojas Alou, with each parent contributing half of the double surname. The paternal half is normally used in everyday life, and in the Dominican people know Felipe, Mateo, and Jesús as the Rojas brothers. During Felipe’s time in the American minor leagues he began to be called (incorrectly) Felipe Alou, rhyming (again incorrectly) with “lew” rather than “low.” However, he did not feel empowered enough to correct the error. Two of his brothers, Mateo and Jesús, followed him to American baseball and also, because of the error with Felipe, assumed the surname Alou during their Stateside careers. Similarly, three of Felipe’s sons played professionally, one becoming a star, and all of them used the name Alou even though it was not a part of their name at all (it being their grandmother’s maiden name, not their mother’s). For convenience, this biography will refer to the subject by the name most readers are familiar with: Felipe Alou.

Alou spent six years in local schools and went to high school in Santo Domingo, a 12mile trip he often made on foot. He also worked on his uncle’s farm and helped his father with his carpentry business. An excellent student, he became a member of the Dominican national track team, running sprints and throwing the discus and javelin. As a senior in high school, he participated in the 1954 Central American Games in Mexico City. Though track kept him from playing high school baseball, he did play and star for local amateur teams.5

In 1954 Alou entered the University of Santo Domingo in its premed program, part of his parents’ dream that he become a doctor. Alou batted cleanup for the team that won the 1955 collegiate championship. He returned to Mexico City for the Pan-American Games, intending to run sprints and throw the javelin, but at the last minute was removed from the track team and placed on the baseball team. He got four hits in the final game against the United States as the Dominican Republic won the gold medal.6

After the tournament Alou received many offers from the major leagues, which at first he had no intention of taking. His resolution lasted until his father and uncle both lost their jobs. As it happened, his university coach, Horacio Martínez, doubled as a bird dog scout for the New York Giants. “Rabbit” Martínez had played shortstop for Alex Pómpez, owner of the New York Cubans, and later a Giants scout. Alou signed in November 1955 for $200, which paid off his parents’ grocery bill. More importantly, he had a job. Despite his parents’ mixed feelings, “we needed somebody to start contributing some earnings to the house.”7

Alou began his professional career in Lake Charles, Louisiana, helping to integrate the Evangeline League. Soon after he arrived, the league voted to expel Lake Charles and Lafayette (the two clubs that had black players).8 Instead, the blacks were shifted to other teams in other leagues; Alou, having just arrived in the United States, rode a bus to Cocoa, Florida, to play in the Florida State League. Desperately homesick, and stung by racism for the first time in his life, he pulled it together enough to hit a league-leading .380 with 21 home runs. On September 23, far away in New York, Ozzie Virgil made his debut with the Giants, becoming the first Dominican native to play in the major leagues. (Because Virgil had gone to high school in New York City, his path to the majors was different from Alou’s.)

Alou began 1957 at Triple-A Minneapolis, but his .211 average in 24 games led to a demotion to Springfield, Massachusetts, where he recovered with a .306 average and 12 home runs. It could have been better— Alou was hitting over .380 in midseason before injuring his right leg on a slide into home plate; he hobbled the rest of the year. Nonetheless, his season earned him an invitation to major league camp in 1958 and a raise to $750 a month. Alou spent very little of it—he kept enough to live on and sent the rest home to his family. During the offseason, the New York Giants moved to San Francisco, and their top minor league affiliate was now in Phoenix, where Alou was ultimately assigned. Batting leadoff for the first time, he hit .319 with 13 home runs in just 55 games before the Giants brought him to the big leagues.

On June 8 Alou became the second Dominican major leaguer, playing right field and leading off at San Francisco’s Seals Stadium. He singled and doubled off Cincinnati’s Brooks Lawrence in his first two at bats, and, three days later, got his first home run off Pittsburgh’s Vernon Law. After a hot start that kept him over .300 for a month, he cooled down in July and finished at .253 with 4 home runs in 182 at bats.

In his first few years Alou could never quite establish himself as a regular player, hampered mostly by the competition on his own team. Beginning in about 1958, a large wave of young players, mostly African-Americans and Latinos, arrived with the Giants. In just this single season, the Giants debuted Alou, Orlando Cepeda, Willie Kirkland, and Leon Wagner. Bill White had a fine rookie year in 1956, went into the Army, came back in late 1958 and had no place to play. Felipe Alou competed with all these guys, along with several others on their way; Willie McCovey and José Pagán joined the club in 1959.

Most of these players were outfielders and first basemen. Alou had the advantage of being athletic enough to play center field, but with the peerless Willie Mays on hand, that skill did not help Alou get on the field. He played as a fourth outfielder in 1959, but with Willie McCovey hitting .372 with 29 home runs for Phoenix in late July, the Giants wanted to bring McCovey up and send Alou back down. With just a year’s seniority under his belt, the 24-year-old told the Giants he would not go back to the minors.

His wife was going through a difficult pregnancy, and Alou did not believe the move to Phoenix and the return to San Francisco in September would help. Instead, he told Giants manager Bill Rigney that they would go home. The Alous checked out of their apartment and booked flights to Santo Domingo. The Giants backed down, and instead made room for McCovey by making Hank Sauer a coach.9

Still, the addition of McCovey meant that either he or Orlando Cepeda had to play the outfield, and, with Willie Mays out there already, that left just one spot for Alou and several other qualified players to fight for. Over the 1959 and 1960 seasons combined, Alou hit .269 with 18 home runs in 569 at bats. In 1961, under new manager Alvin Dark, Alou played most of the time, got 447 at bats, and responded with 18 home runs and a .289 average.

While Alou’s star was rising in his profession, something else became even more central to his life. “The day I joined the Giants in San Francisco was one of the most important days of my life,” recalled Alou. “That was the day my new teammate Al Worthington introduced me to Jesús Christ.” Alou had often read the Bible in the minor leagues because he had a Spanish-language version and it became his only reading material. But because of Worthington, and later Lindy McDaniel (“who baptized me into the new faith”), Alou became one of the more devout Christians in baseball. His devotion caused some discomfort within his own family, but they remained very close.10

Felipe’s brother Mateo, generally called Matty in the States, signed with the Giants before the 1957 season and began to work his way up through the minors. He debuted in late 1960, and reached the majors full time in 1961, hitting .310 in 200 at bats. Although his presence was great for Felipe personally, Matty also was another outfielder—by September, Dark was platooning the two Alous in right field. Meanwhile, 19-year-old brother Jesús, yet another outfielder, was hitting .336 for a Giants affiliate in the Northwest League.

Felipe finally broke through as a fulltime player in 1962, winning the right field job outright and keeping it all season. In 605 at bats, Alou hit .316 with 25 home runs. He was selected to the NL AllStar team in July, coming in for Roberto Clemente and hitting a sacrifice fly in his only plate appearance. More importantly, the Giants won the NL pennant, overcoming a fourgame deficit with seven games to go to tie the Dodgers, then winning a threegame pennant playoff. In the playoff series, Alou was 4for12 with two doubles.

The 1962 World Series was a classic sevengame affair pitting the Giants and the New York Yankees. Alou played every inning in right field, and managed 7 hits in 29 at bats. But he has never forgotten his last chance, in the ninth inning of the final game, with the Giants trailing 10. Matty led off with a bunt single, and Felipe tried to sacrifice him to second base. “I was asked to bunt, and I bunted poorly and the ball went foul. Then, with the infield charging for the bunt, I swung at a bad pitch and fouled it off for strike two. Then I struck out.”

“That was the lowest point of my career. This is something I am going to die with because I failed in that situation.” Alou was not often asked to bunt, but he did not blame Dark. He believed, then and later, that he should have been practicing bunting in case he was asked. Years later, as a manager, he obsessed over his clubs being capable of bunting.11 After another out, Willie Mays doubled Matty to third, but they were both stranded when McCovey lined out to second base, ending the game and Series.

The Giants fell back to third place in 1963, though Alou had another fine season—20 home runs and a .281 batting average. The highlight of the year came in September when his brother Jesús was recalled from Triple-A Tacoma to join Felipe and Matty. Late in the game on September 15, Jesús and Matty replaced Mays and McCovey, creating an all-Alou outfield. The brothers repeated this two more times that month, and appeared in the box score together a few other times. This feat has never been repeated in the regular season, and Felipe has a theory as to why. “Because people don’t want to have children,” he reasoned. The odds of three boys, all ballplayers, all on the same team, are quite remote.12

Meanwhile, in 1963 Alou found himself embroiled in some politics with the baseball establishment. Throughout his professional career, Felipe returned home every October and played baseball in the Dominican Winter League. On his way up to the majors, he won back-to-back batting titles in 1958–59 and 1959–60. A growing list of fellow major leaguers joined Alou, including his brothers, Manny Mota, Juan Marichal and more. The Alous and Marichal usually played for Leones del Escogido in Santo Domingo, which won five of six championships beginning with the 1955–56 season. In 1956, Escogido club president Paco Martínez Alba—brother-in-law of Rafael Trujillo, the longtime Dominican strongman—formed a working agreement with the Giants.

Trujillo was assassinated in 1961, leaving the country in the hands of the military. The Winter League season was shortened in 1961–62, and cancelled outright in 1962–63. The Dominican government arranged a series of games with a touring team of Cuban players who were living in the US (exiled from their own country, and their own winter league). Among those who participated were Felipe Alou and Juan Marichal. Baseball commissioner Ford Frick, deeming these games “unauthorized,” fined the players $250 each.

Many of the Dominican players were upset, but it was Alou who went public. In the spring of 1963, Alou suggested that Latin players have a representative in the commissioner’s office, someone who understood Latin culture and politics, and could explain their unique set of problems. “They do not understand,” Alou said, “that these are our people and we owe it to them to play for them.”13 In December 1965, Commissioner William Eckert hired Bobby Maduro to fill exactly this position.

Alou expanded on his people’s grievances in a courageous firstperson account in Sport (as told to Arnold Hano) that fall. “When the military junta ‘asked’ you to do something, you did it. If I had not played, I would have been called a Communist.” Most Latin players came from very impoverished circumstances, and earning the extra money in the offseason (there were no other jobs available) helped feed huge extended families. In the US, the players were often isolated from their teammates by language, and often criticized or even disciplined for speaking Spanish amongst themselves. Alou was very complimentary of the United States, calling it a “wonderful country,” but left no doubt where his heart lay. “I am a Dominican. It is my country. And I love it.”14 Alou pulled no punches, criticizing Frick and also Alvin Dark, his own manager. In the words of writer Rob Ruck, “Nobody had ever spoken so eloquently or forcefully about Latin ballplayers, much less prescribed how baseball could and should address their unique concerns.”15

In early December, not long after the article in Sport appeared, the Giants traded Alou to the Milwaukee Braves as part of a seven-player trade. Whether the deal was related to Alou’s outspokenness is unclear, but his Latino teammates, including Cepeda, Marichal, and Pagán, were devastated. “I think that was one of the biggest mistakes the Giants ever made,” said Marichal decades later.16 The Giants did have a surplus of outfielders, and needed the pitching they acquired. Jesús Alou, who many thought would surpass both his brothers, was anointed as the new Giant right fielder. Alou spent the next six years with the Braves. Before reporting in 1964 he had injured his knee playing in the Dominican Winter League. He played through it, knowing that the Braves needed him to play center field, but he got off to a slow start hitting and fielding. In June manager Bobby Bragan (faced with an outfield surplus with the sudden emergence of Rico Carty, a rookie Dominican) asked Alou to play first base, and a few games later he tore cartilage in his knee reaching for a ground ball. He missed a month of action, and hit just .253 with nine home runs on the season. In 1965 he recovered nicely, alternating between first base and the outfield, hitting .297 with 23 home runs.

In 1966 the Braves moved to Atlanta, and Alou responded to the hot climate with his best season. Again playing first base and all three outfield positions, Alou hit .327 with 31 home runs, leading the NL with 218 hits, 122 runs scored, and 355 total bases. He lost out on the league batting title to his brother Matty (.342), who had been traded to Pittsburgh and was capitalizing on his first chance at regular playing time. Felipe returned to the All-Star game, though he did not see any action.

The Atlanta writers named Alou the team MVP, and some of his teammates were in awe. “I’ve never seen anyone stand out head and shoulders the way Felipe did,” said catcher Joe Torre. “I’ve never seen anyone hit so consistently well all season long,” added Henry Aaron. Alou parried such talk: “If a team isn’t going right, what can one man do to help? I think this stuff about leading a team, I wonder if that is really possible.” But it was not just his ball-playing. Gene Oliver, a white teammate who lost his first base job to Alou, said, “He is the kind of man you hope your kid will grow up to be.”17

Alou struggled in 1967, suffering from bone chips in his elbow and falling to .274 with just 15 home runs. He recovered to hit .317 in 1968 (a year that saw league averages plummet to .243), playing in the All-Star game again. His batting average was third highest in the league, and he tied Pete Rose for the lead with 210 hits. After three years of moving around the diamond, Alou played 156 times in center field under new manager Lum Harris.

Alou got off to a great start in 1969, hitting well over .300 through May. On June 2 he broke a finger and missed two weeks after he was hit by a pitch thrown by the Cardinals’ Chuck Taylor. During his absence the Braves acquired Tony González from San Diego, and when Alou returned the two platooned in center field. During the Braves’ successful drive for the division title, and the subsequent playoff loss to the Mets, Alou got little playing time. For the season he hit just .282 with five home runs. With an outfield surplus, Atlanta dealt the 34-year-old to Oakland for pitcher Jim Nash over the winter.

No longer a star player, in 1970 Alou was the elder statesman on a young A’s team filled with up and coming stars. He hit .271 in 154 games. Just a few days into the 1971 season, Oakland dealt Alou to the Yankees for two young pitchers, making room for Joe Rudi in left field. Alou played most of the next three years in New York, hitting .289, .278 and finally .236, moving between the outfield and first base all three seasons. He played 19 games for Montreal in September 1973, and got three at bats for Milwaukee the next April before drawing his final release. Felipe was sad, saying he would “have to get used to the life of a man who can’t play baseball.”18

Alou joined the Montreal Expos organization as an instructor in 1976, but suffered the tragedy of his life in 1976 when his oldest boy, Felipe Jr., an aspiring ballplayer, jumped into a shallow pool and drowned. Alou was so broken up he did not work at all that season, and could not talk about the tragedy for many years. He rejoined the Expos the next year, and spent the next seventeen years as a minor league manager (with a few stints as a major league coach). In the minors, he piloted West Palm Beach, Memphis, Denver, Wichita, and Indianapolis, earning a reputation as a serious and respected teacher of young players. He apparently was offered the job in 1985 to manage the San Francisco Giants but turned it down out of loyalty to the Expos.

In the winter months, Felipe transitioned from player to manager of his longtime team, the Leones del Escogido in the Dominican Republic. Alou managed the club to four league championships (1980–81, 1981–82; 1989–90, 1991–92). Previously, he had also won two Venezuelan titles as skipper of the Caracas Leones (1977–78, 1979–80). In the mid1980s, he managed Caguas in the Puerto Rican Winter League as well.

The genuinely devoted Alou, who did not drink or smoke or socialize much, has been married four times and has fathered eleven children. As a young man he married María Beltré, from his hometown, and the couple had four children: Felipe Jr., María, José, and Moisés. He and Beverley Martin, from Atlanta, had three girls: Christia, Cheri, and Jennifer. His third wife was Elsa Brens, from the Dominican, and the couple had Felipe José and Luis Emilio. In 1985, he married Lucie Gagnon, a French-Canadian, and had two more children, Valerie and Felipe Jr.

“People ask how a man who likes to be home with his family gets married four times,” Alou said in 1995. “All the evils that go on in life, the evils of the life of a traveling ballplayer, I wasn’t immune to that. But I loved all my wives and children. … I’ve been a lucky man. I had two children in my fifties, and God gave us other Felipes.”19 Among his children, José and Felipe José became minor league players, and Moisés made it to the Majors.

In 1986 Alou returned to manage at Single-A West Palm Beach, and remained there for six years, an eternity for a minor-league manager. In 1992 he returned to the major leagues as the bench coach for Montreal manager Tom Runnells. After a sluggish start (17–20), general manager Dan Duquette fired Runnells and hired Alou to finish the season. The young Expos responded with a 70–55 record to finish a strong second to the Pittsburgh Pirates. The 57-year-old Alou’s job was secure. “The biggest mistake I’ve made in my career,” said Duquette, “was not recognizing his ability then to be a terrific major league manager. He’s one of the best in the game.”20 He was the first of his countrymen to manage a bigleague team.

Alou took over a Montreal club filled with young talent, including Larry Walker, Marquis Grissom, Delino DeShields, and Wil Cordero. One of the team’s best relief pitchers was Mel Rojas, who was Felipe’s nephew (the son of his half-brother). The team’s left fielder was 25-year-old Moisés Alou, Felipe’s son. Moisés had not grown up with Felipe (his parents had divorced when Moisés was two), but they talked frequently and saw each other occasionally over the winter months. “I was the happiest kid in the world,” Moisés recalled. “He was the most famous player, maybe the most famous person, on the island, and he was my father.”21 Alou was a good young player who developed rapidly under his father’s tutelage, turning into a six-time AllStar and one of the better hitters in the National League.

The Expos finished 94–68 in 1993, just three games behind the first-place Phillies. Over the offseason, Duquette traded second baseman DeShields to Los Angeles for 21-year-old pitcher Pedro Martínez, a Dominican who joined Ken Hill and Jeff Fassero to give Alou one of the league’s best starting staffs. The fortified club soared to the best record in baseball in 1994, a great team that could hit, field, run, and pitch. Unfortunately for Alou and his team, the season was ended in early August by a players’ strike, and the club was not able to continue its quest for a championship. The club’s 74–40 pace, if maintained over the full schedule, would have yielded 105 wins, the most since the 1986 Mets. Alou was named the National League Manager of the Year.

Compounding the tragedy, the team’s ownership was not willing to spend the necessary money to keep the team intact. Before the 1995 season got underway, the Expos had lost Walker, Grissom, Hill and John Wetteland. Alou’s club fell all the way to last place in 1995, before clawing their way back to 88 wins and second place in 1996. But soon Cordero and Fassero departed, followed by Moisés Alou and Pedro Martínez. As the club continued to develop good players (Vladimir Guerrero, Rondell White, Orlando Cabrera and Javier Vázquez arrived in the late 1990s), the club’s five straight fourthplace finishes did not harm Alou’s reputation as a manager. It was understood that Alou was doing a fine job with his youngsters, but that the team was not willing to keep them once they attained the seniority that allowed them to earn big money. After another mediocre start in 1991 (21–32), Alou finally was released as manager after nine years.

He spent 2002 as the bench coach for the Tigers (working under Luis Pujols, who had been Alou’s bench coach in Montreal). After the 2002 season Alou returned to San Francisco to manage the Giants. Under Dusty Baker, the club had reached the World Series in 2002, but after the season Baker left the club in a contract dispute, joining the Chicago Cubs. The 67-year-old Alou took over.

The Giants’ team and personality was dominated by the late-career Barry Bonds, who had set the single-season home record in 2001 and whose days were now filled with home runs, bases on balls, and (ever increasingly) steroid allegations. Alou’s first club won 100 games, an improvement on the World Series team that had won 95 and the NL wild card. Unfortunately, the 2003 club was upset in the playoffs by the young Florida Marlins. Bonds missed 30 games but managed to hit .341 with 45 home runs and 148 walks. The next season Bonds walked a record 232 times and won the batting title, but the club fell to 91 wins, and then to 75 wins in 2005 with Bonds hurt. Moisés Alou rejoined his father in 2005, and had two pretty good seasons with the Giants. After the 2006 season, the 71-year-old Felipe Alou was released from his job as manager.

Alou remained a beloved figure in San Francisco, and was offered a job as a special assistant to general manager Brian Sabean. “I am truly overjoyed to have Felipe remain with the Giants organization,” said Sabean. “As he was during his four years as our manager, Felipe will continue to be a huge asset to the ballclub going forward.”22 Alou has worked as a Major League scout, and minor league instructor, helping Sabean on player evaluation. In 2010 Alou received his first championship ring after the Giants defeated the Rangers in the World Series.

In 2012 he was beginning his sixth season in this position, 57 years after signing his first contract with the Giants. He had begun his career as a stranger in a strange land, but had become one of baseball’s most respected men. A three-time All-Star turned into an award-winning manager, who helped many of the game’s greatest stars as they began their careers. But he remains most famous as the eldest in one of baseball’s greatest families, the brother and father to fellow All-Stars. Very few men have left a greater mark on baseball than Felipe Rojas Alou.

MARK ARMOUR is the director of the Baseball Biography Project, and hard at work on another book with Dan Levitt. He lives in Oregon’s Willamette Valley with Jane, Maya, and Drew.

Sources

Thanks to Rory Costello for his help, especially for his straightening out my understanding of Felipe Rojas Alou’s name. (This article appeared on February 28, 2012 on the SABR BioProject website.)

Photo credits: Felipe Alou, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Notes

1. Michael Farber, “Diamond Heirs,” Sports Illustrated, June 19, 1985.

2. Rob Ruck, Raceball—How the Major Leagues Colonized the Black and Latin Game (Boston: Beacon Press, 2011), 164.

3. Rob Ruck, Raceball, 154.

4. Felipe Alou with Herm Weiskopf, My Life and Baseball (Waco, Texas: Word Books, 1967), 113.

5. Alou and Weiskopf, My Life and Baseball, 1417.

6. Alou and Weiskopf, My Life and Baseball, 1821.

7. Steve Bilker, The Original San Francisco Giants: The Giants of ’58 (Sports Publishing, Inc., 2001), 68.

8. The Sporting News, May 16, 1956, 37.

9. Steve Bilker, The Original San Francisco Giants, 68.

10. Steve Bilker, The Original San Francisco Giants, 66.

11. Steve Bilker, The Original San Francisco Giants, 69.

12. Steve Bilker, The Original San Francisco Giants, 70.

13. Bob Stevens, “Felipe Suggests Latins Have Rep in Frick’s Office,” The Sporting News, March 16, 1963, 11.

14. Felipe Alou with Arnold Hano, “LatinAmerican Ballplayers Need a Bill of Rights,” Sport, November, 1963, 21.

15. Rob Ruck, Raceball, 164.

16. Rob Ruck, Raceball, 164.

17. John Devaney, “Felipe Alou: The Gentle Howitzer,” Sport, June 1967, 63.

18. Lou Chapman, “Brewers Salute Tom Murphy as Bullpen Savior,” The Sporting News, May 18, 1974, 9.

19. Michael Farber, “Diamond Heirs.”

20. Michael Farber, “Diamond Heirs.”

21. Michael Farber, “Diamond Heirs.”

22. Associated Press, “Alou returns to Giants as special assistant,” ESPN.com.