County Stadium (Milwaukee)

This article was written by Gregg Hoffmann

Milwaukee was ready for major-league baseball in 1953.

Milwaukee was ready for major-league baseball in 1953.

More than 10,000 people turned out for an open house at the ballpark on March 15, three days before the Braves’ move to Milwaukee was approved by the National League owners.

Another large crowd turned out on April 6 and braved sleet and cold just to watch an exhibition game against the Boston Red Sox which lasted two innings. When County Stadium opened for the first Milwaukee Braves regular-season game on Tuesday afternoon, April 14, fans lined up hours before the gates opened in order to be among the first to get inside.

Fans that Opening Day started tailgating, a tradition that continues in Milwaukee, while bands played and dignitaries flocked to the new ballpark. A crowd of 34,357 packed the stadium and thousands more listened on radios outside and in homes and pubs around the town. Fans cheered wildly for every hit, every strike, and everything else. It was all new and exciting.

The game lived up to the excitement the day promised, with center fielder Billy Bruton winning the 3-2 contest on a disputed tenth-inning home run that bounced off the glove of a leaping Enos Slaughter, the Cardinals’ right fielder.

It had been a long journey to that opener. County officials and others had talked about building a “major league” ballpark in Milwaukee since the 19-teens. Several locations were bandied about over the years, according to Milwaukee County records. Local politicians had differing opinions about where best to situate the stadium. Transportation, parking, and the demolition of existing buildings all factored in, delaying the project by decades.

Officials originally planned to build the stadium for the Milwaukee Brewers of the Triple-A American Association, an affiliate of the Boston Braves. In September 1948, they finally focused on Story Quarry, an abandoned landfill on the west side of the city.

Construction began in October 1950. Officials had to scramble to get materials, in part due to the demands of the Korean War. They were able to convince federal officials that construction had begun before the war rationing was imposed and were thus able to get the necessary steel. Between the material shortage and a required land swap with the adjacent Soldiers Home, the creation of Milwaukee’s new ballpark literally required an act of Congress.

The ballpark, whose cost was initially put at $5 million, was the first in the country to be paid for by public funds. The funds came from a combination of city and County of Milwaukee bonds. As for the site, the US Congress in 1949 approved the leasing of 22 acres of federally-owned land for $1 a year and the county bought another 98 acres. A federal agency, the National Production Authority, also had to approve the construction after it had banned any new recreational facilities because of the need for steel and other materials for the Korean War. The stadium project was approved because groundbreaking had taken place a week before the ban was put into effect.

Osborn Engineering was the architect. Hunzinger Construction was the general contractor on the project. The stadium was built primarily for baseball, but was intended to be multipurpose, like Exhibition Stadium in Toronto and Municipal Stadium in Cleveland. (In 1988 home-game scenes for the movie Major League, which dealt with the Cleveland Indians, were shot at County Stadium during the summer of 1988, in part because it resembled Municipal Stadium, which was undergoing work at the time.)

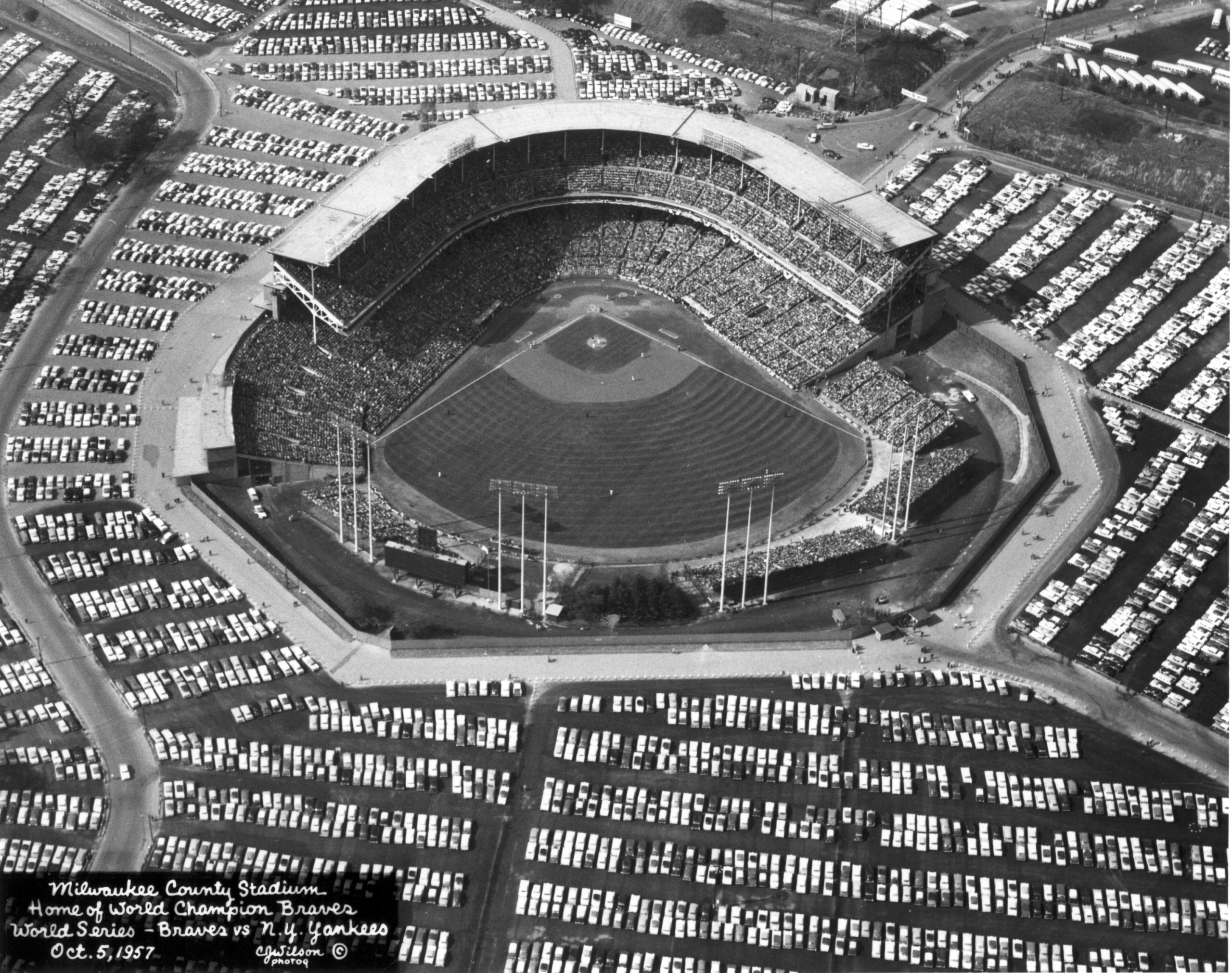

The new stadium featured a double-decked grandstand and mezzanine that ran from first base to third base. The lower grandstand extended down the right-field line and to the foul pole. Temporary bleachers occupied the space down the left-field line, as well as several bleacher sections in the outfield. Over the years, a picnic area in left field became a popular feature of the ballpark. So did a grove of fir and spruce trees planted in March 1954, which acquired the name Perini’s Woods. Throughout its history, County Stadium was expanded piecemeal, and eventually reached a capacity of 55,000-plus.

It was considered state-of-the-art in its early days and helped to lure the Braves from Boston. The franchise shift also paved the way for other teams, notably the Dodgers and Giants, to join the westward migration.

County Stadium was ready to go by spring 1953, but the Brewers, the Braves’ top minor-league team, never played there. Instead, the Boston Braves owners, who had struggled for years at the gate as the second team to the Red Sox, applied for permission to move to Milwaukee.

Lou Perini, principal owner of the Braves, had blocked the St. Louis Browns from moving to Milwaukee earlier. Perini was able to persuade the National League owners to allow his club to move, only three weeks before the season was to start.

With Charlie Grimm, who had piloted the Brewers, as the Braves manager, the club immediately became competitive. Eddie Mathews, Johnny Logan, and others who had come through Milwaukee as minor leaguers, became fan favorites. The 1953 Braves finished 92-62, good for second place, in their first season and set a National League attendance record of 1,826,397.

The Braves continued to contend in their early years in Milwaukee; in fact, they never had a losing season in their 13 years there. Their fewest wins up to the 1957 championship season was 85 in 1955. They finished no worse than third place from 1953 through 1960.

In 1956 the Braves finished only one game behind the Brooklyn Dodgers. They seemed poised to make the move to the top after that season. Fred Haney, a contrast in managing style to the affable Grimm, took over as the skipper in mid-June of 1956 and meant business from the beginning.

The Braves made the move to first in 1957 when they won 95 games. One of the biggest moments in County Stadium history came on September 23, 1957. Henry Aaron, who was the Most Valuable Player that season, homered in the 11th inning off the St. Louis Cardinals’ Billy Muffett to give the Braves a 4-2 victory that clinched the pennant. Aaron has often said that that blast against St. Louis was the biggest of his career, even surpassing the homer in Atlanta that broke Babe Ruth’s record of 714.

County Stadium was decked out in red, white, and blue for the World Series. One member of the Yankees – reported to be manager Casey Stengel – referred to Milwaukee as “bush,” and the fans took that up as their rallying cry, with signs “Bushville Wins” once the Braves won.

The Braves clinched the World Series in New York in Game Seven behind Lew Burdette’s third win of the Series. Game Five goes down as one of the great games in the stadium’s history. Each team had won two games. Burdette, who had beaten the Yankees 4-2 in Game Two, was opposed by Whitey Ford, who had defeated the Braves 3-1 in Game One. In the sixth inning of a scoreless battle, the Braves broke through with a run. With two out and nobody on base, Mathews bounced a chopper toward second baseman Jerry Coleman. Hustling down the line, Mathews narrowly beat the throw to first. Aaron blooped a single to right-center, sending Mathews to third base. Then Joe Adcock smacked a line-drive single to right that scored Mathews. The single tally was all Burdette needed. He shut out the Yankees, 1-0, on seven hits.

From 1954 through 1957 the Braves drew more than two million fans each season. On June 12, 1954, journeyman Braves pitcher Jim Wilson fired the first major-league no-hitter in Milwaukee, against the Philadelphia Phillies. The cover of the inaugural issue of Sports Illustrated, on August 16, 1954, displayed a photo of Eddie Mathews batting in County Stadium. On July 12, 1955, the stadium hosted its first All-Star Game. More than 45,000 fans saw the National League roar back from a 5-0 deficit to win 6-5 in 12 innings. Attendance peaked at 2,215,404 in 1957 but slipped to 1,971,101 in 1958. In 1959, the year the Braves lost the pennant to the Los Angeles Dodgers in two games during a best-of-three playoff, attendance dropped to 1,749,112.

The subsequent years still had winning seasons and historic events, including two no-hitters by Spahn and one by Burdette, Pittsburgh’s Harvey Haddix hurling 12 perfect innings in 1959 only to lose to the Braves in the 13th, San Francisco’s Willie Mays hitting four home runs in a game in 1961 and many other thrills. But the magical team that won the championship gradually broke up. The Miracle in Milwaukee had run its course.

From 1960 through 1965, their last season in Milwaukee, the Braves never won fewer than 83 games. Even so, attendance continued to decline, dipping under a million for the first time in 1962. Rumors of the club moving already were circulating.

The 1964 season was marred by rumors about the Braves’ status in Milwaukee, and outright feuding began between the ballclub and members of the community. County Board Chairman Eugene Grobschmidt intimated that he thought the Braves weren’t making an all-out effort on the field. “I don’t think the players or somebody isn’t doing something right here,” Grobschmidt said with more passion than grammar.[1]

Manager Bobby Bragan, who never caught on with the Milwaukee fans, snapped back at Grobschmidt. Club president John McHale said, “Grobschmidt had better have proof … or be prepared to retract the statement.” McHale said the team would even consider a lawsuit.[2]

Congressman Henry Reuss, who represented a Milwaukee district, talked about trying to keep the club in Milwaukee through an antitrust suit against Major League Baseball. Milwaukee County officials indicated a willingness to force the team to stay through the end of 1965 through legal maneuvering.

The final parting of the Braves from Milwaukee was a bitter one. Both sides took legal action and hurled verbal hardballs. Warren Spahn, who was sold to the Mets in November 1964, and Oshkosh native Billy Hoeft, who was released in the spring of 1965, both said the Braves had tried not to win in 1964.[3]

“We should have won the pennant,” Hoeft said. “But they didn’t want to win.”[4] Bragan, a Southerner who supposedly wanted the team below the Mason-Dixon Line, was looked at as the guy who did management’s dirty work on the field.

Because of a judge’s ruling regarding the County Stadium lease, the Braves had to play the 1965 season in Milwaukee. By July 28 of that season, however, corporation papers were filed for the Milwaukee Brewers Baseball Club, and the search for a new team was on. That served as an admission that the Braves were gone. From 1966 through 1969 Milwaukee was a city in search of a ballclub to call its own.

Perhaps the saddest day in County Stadium’s history came when the Braves played their last game there, on September 22, 1965. Mathews recalled his last at-bat. A crowd of 12,577 gave him a standing ovation, and Mathews admitted his eyes teared up. “The fans gave me about a two-minute standing ovation,” he recalled. “I was overwhelmed. I tried to bat, but I had to step out of the batter’s box three or four times.”[5]

Some legal action still took place after the season. Judge Elmer Roller ruled in the spring of 1966 that the Braves and the National League had violated Wisconsin’s antitrust laws and must either give Milwaukee a new franchise or return to play in County Stadium. To that verdict, Braves executive William Bartholomay said, “There is as much chance of the Braves playing in Milwaukee this summer as there is the New York Yankees.”[6] The Wisconsin Supreme Court overruled Roller.

County Stadium was without baseball. Officials tried to keep some revenue coming in with religious revivals, tractor pulls, wrestling matches, concerts, and other events. The Green Bay Packers, who had played some of their games in the stadium since 1953, continued to play there. But without baseball, the ballpark seemed like a home without a family.

Allan “Bud” Selig, who owned a car-leasing business in Milwaukee, organized a group to get baseball back to Milwaukee and the stadium. They almost bought the Chicago White Sox, who played 20 games at the stadium in 1968 and 1969. But that deal fell through. Selig’s group eventually bought the bankrupt Seattle Pilots of the American League, in a move that had almost eerie similarities to the Braves move in 1953, coming only weeks before the opening of the 1970 season.

Milwaukee fans were excited to have baseball back in town, but they warmed up to the Brewers more slowly than they did the Braves; home attendance did not top one million until 1973. The Brewers also struggled on the field in the early years, and even the acquisition of Henry Aaron before the 1975 season didn’t move the Brewers out of last place. Aaron hit the final home run (No. 755) of his 23-year career on July 20, 1976, at County Stadium.

The Brewers finally built a winning team from the 1978 through the 1982 seasons with Harry Dalton as general manager. In 1982, the World Series returned to County Stadium, and the franchise drew over two million in home attendance in 1983.The Brewers continued in the stadium for almost two more decades, but by the early 1990s it was clear that the ballpark had become outdated. Selig started talking about the need for a new stadium to keep baseball viable in Milwaukee.

After a contentious political debate about financing, Miller Park was eventually approved. For a couple of seasons, fans could watch the modern facility being built beyond the center-field wall of County Stadium.

The old ballpark had to work overtime after a construction accident killed three workers and delayed the opening of Miller Park for a year. Eventually County Stadium was closed, with its last game on September 28, 2000. Some of the greats who had played there came back for an emotional ceremony to say goodbye to what announcer Bob Uecker called an “old friend.” Uecker read a short goodbye for the old park as the lights were turned off, standard by standard. He closed with “So long, old friend, and goodnight everybody.”[7]

County Stadium’s demolition was completed on February 21, 2001. However, the infield portion of the field was transformed into a youth playing field under the name of Helfaer Park.

This biography is included in the book “Thar’s Joy in Braveland! The 1957 Milwaukee Braves” (SABR, 2014), edited by Gregory H. Wolf. To download the free e-book or purchase the paperback edition, click here.

Sources

Buege, Bob, Milwaukee Braves: A Baseball Eulogy (Milwaukee: Douglas American Sports Publications, 1988).

Gershman, Michael, Diamonds: The Evolution of the Ballpark (New York: Mariner Books, 1995).

Hoffmann, Gregg, Down in the Valley: The History of Milwaukee County Stadium (Holt, Michigan: Partners Publishers Group, 2000).

Lowry, Philip J., Green Cathedrals: Ultimate Celebration of All 273 Major League and Negro League Ballparks (New York: Walker and Company, 2006).

Milwaukee Journal (various issues ranging from 1948 until 2001).

Milwaukee Sentinel (various issues ranging from 1948 to 2001).

Milwaukee County Historical Association documents (1948-53 and 1964-66).

Povletich, William, Milwaukee Braves: Heroes and Heartbreak (Madison, Wisconsin: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2009).

Wisconsin State Historical Society documents (1948-53).

Interviews (done from 1994 to 1999 for Down in the Valley) with baseball commissioner and former Brewers owner Bud Selig, former Milwaukee Mayor Frank Zeidler, former Braves players Eddie Mathews, Henry Aaron, Warren Spahn, Bob Uecker, and Johnny Logan, former Brewers players Robin Yount, and Jim Gantner, and others.

Notes

[1] Lou Chapman, “Braves ‘Call Off’ Suit,” Milwaukee Sentinel, July 10, 1964, II, 4.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Milton Gross, “Spahn Wonders What Mets Paid,” Milwaukee Journal, November 24, 1964, II, 10.

[4] Bob Wolf, “’Bragan Tried to Lose’ – Hoeft,” Milwaukee Journal, April 1, 1965, II, 17.

[5] Eddie Mathews and Bob Buege, Eddie Mathews and the National Pastime (Milwaukee: Douglas American Sports Publications, 1988, 253).

[6] Raymond E. McBride, “Braves Say They Won’t Return Despite Judge Roller’s Decision,” Milwaukee Journal, April 14, 1966, 1.

[7] Crocker Stephenson, “So Long, Old Friend, Crowd Says to Ballpark,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, September 29, 2000, 7A.