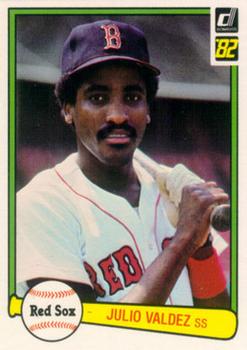

Julio Valdéz

Julio Valdéz, a Dominican infielder, played parts of four seasons with the Boston Red Sox in the early 1980s. As a utilityman who’d played only 65 major-league games, Valdéz made newspaper headlines in the spring of 1983 as the subject of a rape allegation. Although a grand jury refused to indict him, Valdéz never got another chance in the majors. Yet his work ethic, which he learned on his homeland’s dusty fields, helped him overcome obstacles and stay involved in the game he loved beyond his playing days. He has coached in the Chicago Cubs system and also managed clubs in the Dominican Summer League.

Julio Valdéz, a Dominican infielder, played parts of four seasons with the Boston Red Sox in the early 1980s. As a utilityman who’d played only 65 major-league games, Valdéz made newspaper headlines in the spring of 1983 as the subject of a rape allegation. Although a grand jury refused to indict him, Valdéz never got another chance in the majors. Yet his work ethic, which he learned on his homeland’s dusty fields, helped him overcome obstacles and stay involved in the game he loved beyond his playing days. He has coached in the Chicago Cubs system and also managed clubs in the Dominican Summer League.

Julio Julián Castillo Valdéz was born June 3, 1956, in San Cristóbal. This town is about 25 miles west of Santo Domingo, the capital of the Dominican Republic. Young Julio grew up in Nizao, in the province of Peravia, a little further west on the Caribbean Sea coast.

Valdéz was known by his maternal family name. His parents — Manuel De Jesús Castillo and Minerva Aurora Valdéz — were never married. Julio was raised by his grandmother, Augustina, in Nizao. “I took Julio when he was only 14 days old,” Augustina recalled. “His mother couldn’t support him so I became a mother to him.”1 Minerva Valdéz moved to Santo Domingo and washed clothes for a living, sending money home when she could.

The Valdéz family were subsistence farmers, growing just enough to eat and survive in a land with high unemployment and a poor economy.2 As a boy, Julio would help his uncle Carmelo on the family plantation’s fields, where they grew tomatoes and rice. The fields were only reachable by foot or horse, since there were no roads. “He would work in the fields,” Carmelo recalled, “but we didn’t push him too hard, because we knew he was a good (baseball) prospect.”3

Julio finished grades 1-6 at Escuela Primaria Nizao. At age 16, he drove a truck for his father, delivering furniture. His father was the manager of a local slow-pitch softball team. The team needed a shortstop, so he asked Julio to play. “I played every game at short,” Julio said. “That’s the good part about having your father as the manager.”4 Valdéz switched to baseball the next year, playing for Baní (Peravia’s capital) in the Dominican Amateur League. Ramón Naranjo, a scout for the Licey baseball team in the D.R., noticed Valdéz and took him to Santo Domingo.5

Valdéz was signed by Boston as an undrafted free agent in December 1975 at the age of 19. His first taste of professional baseball was with their Class-A club in Winter Haven of the Florida State League in 1976. The Boston Globe’s Peter Gammons mentioned Valdéz as a prospect to keep an eye on during spring training.6 Valdéz batted only .135 in 76 games, splitting time between shortstop and third base.

He spent 1977 with Winston-Salem in the Carolina League (also Class A). His batting improved to .248 with eight home runs, but he also committed a league-high 45 errors in 128 games. In 1978 Valdéz improved at Double-A Bristol (Connecticut). He batted .265, again with eight home runs, and trimmed his errors at shortstop to 39 (still quite high). The improvement at the plate could be attributed to his transformation from batting right-handed to switch-hitting. “I feel very comfortable batting left-handed,” he said in spring training 1979, “I can try to hit the ball to left field, but I can also pull it.”7

One person who took an interest in Valdéz that spring was Red Sox manager Don Zimmer, a shortstop himself in his playing days. “I think he’s an outstanding infielder,” said Zimmer, “great hands and a good arm. He knows how to grab ground balls. He’s like a spider with those long legs and arms. And damn, he’s hit some balls good.”8

In 1979 Julio moved up to Triple-A Pawtucket (Rhode Island). He batted only .222 and again led his league in errors with 34. Valdéz also married his childhood sweetheart Donna in 1979.

Valdéz played another 101 games at Pawtucket in 1980. His batting average declined to .219 but he improved his fielding percentage (.940). He got his first major league action when he was called up by Boston in September. His first appearance was at Fenway Park on September 2 as a ninth-inning replacement for Rick Burleson at shortstop with the Red Sox leading the Angels, 10-2. Valdéz helped turn a double play.

The Red Sox, trailing Seattle 11-1 in the fifth inning on September 7, made a number of substitutions. Valdéz again replaced Burleson at short and recorded his first major-league hit and RBI with a double to right in the sixth off of Byron McLaughlin, bringing in Dwight Evans. The rookie made his first major-league start at shortstop against Cleveland on September 16. He went 2-for-4 in the 9-5 win. Valdéz hit his only major-league home run in the second game of a doubleheader on October 4 off Toronto’s Paul Mirabella, the lone Red Sox run in a 3-1 loss. He finished the season batting .263 (5-for-19) and remained error-prone, committing three in 46 chances (.935).

Valdéz was again playing winter ball for Licey when he read in the newspaper that the Red Sox had traded Burleson, giving him a chance at a roster spot in 1981. So, he spent extra time working on his fielding. “I think it helped,” Valdéz said. “I’m more relaxed. I think about who’s running, how fast he is, how much time I have on each ground ball.”9 However, his chance didn’t come until later. The Red Sox told him they were looking to trade outfielder Tom Poquette to free up a roster spot, but then the players’ strike wiped out a couple of months.

Meanwhile, Valdéz had a strong season at Pawtucket, batting .258 with six home runs and 27 RBIs in 112 games and again showing improvement in the field. In one of those games he fell into a slump — the historic 33-inning marathon against Rochester that started on April 18. When the game was finally finished after play resumed on June 23, Valdéz had gone 2-for-13.

Valdéz returned to Boston in mid-August after play resumed, and appeared in 17 games, starting four. He batted .217 (5-for-23). The team’s main shortstop that year was Glenn Hoffman, with Dave Stapleton backing him up.

Valdéz was out of minor-league options entering the 1982 season. He knew he had an uphill climb. “I don’t feel I have any strong points,” Valdéz said honestly. “I have to work all the time on my hitting and fielding. I know I’m going to have to improve an awful lot in both if I’m to have any chance at playing in the big leagues. I’m a hard worker because that’s the only way I’m going to play in the big leagues.”10 Valdéz spent the entire 1982 season with Boston but appeared in only 28 games, mostly as a late-inning defensive replacement for Hoffman. Valdéz made just one start but had become more surehanded and accurate (.976 fielding percentage).

Valdéz was the starting second baseman for the Red Sox on Opening Day 1983 because Jerry Remy began the year on the disabled list. He started eight games but batted a woeful .125 (3-for-24) and played in only four more games, batting once. He finished what would be his last season in the majors with only 25 at-bats for a career total of 87.

On May 6, Valdéz was arrested during a game at Fenway Park against the Mariners. He was charged with statutory rape and was released on $1,000 cash bail. Lt. Edward McNelly had been investigating claims that a rape had occurred on April 5 at the Fenway Motor Hotel (a Howard Johnson’s) on Boylston Street near Fenway Park. The teenage girl from Berkley, Massachusetts had been missing since March 28 and found near Fenway on April 20. She claimed she had met Valdéz a couple of years earlier in Pawtucket. She claimed she met up with Valdéz on April 5 and lied about her age (17, not 14).

A media fiasco ensued. The alleged victim said she might be pregnant but that she “didn’t want to get him [Valdéz] in trouble.”11 Valdéz pleaded innocent to the statutory rape charges in Roxbury District Court on May 9. The alleged victim was a baseball fan who had autographs of and pictures taken with many Red Sox players.12 Valdéz’s teammate, the always outspoken Dennis “Oil Can” Boyd, remembered the incident and alleged victim in his autobiography three decades later. “The whole thing with Julio Valdéz and the statutory rape arrest was scary,” he wrote, “because a lot of people might have been involved with that girl. She had a reputation with the ballplayers. Still, a lot of players thought she might be lying about her age. I can tell you, there were a lot of nervous people when that [Valdéz’s arrest] happened.”13

The hearing was moved to May 24. Joe Giuliotti of the Boston Herald wrote, “With no regard for his [Valdéz’s] personal safety, McNelly, backed by six other policemen, entered the Red Sox clubhouse. And, by mere coincidence, Boston’s three television stations, alerted by phone calls, were at District Four waiting for the prisoner to be brought in. Valdéz, living in a country that’s strange to him, is also a human being who must be completely bewildered by the events of the past few days. If he is guilty of the charge and if the girl did lie about her age, Valdéz’ only real crime is being stupid and cheating on his wife.”14 Fellow Herald columnist Joe Fitzgerald wrote, “It’s a darned shame, because here’s a life—not to mention a career—which could be shattered by that hanging jury known as public opinion.”15 “Pavlov’s dog could make the same connection,” wrote Michael Madden of the Boston Globe. “Red Sox player. Statutory rape. BIG story. Just like the dog, they all bit without even having to think.”16

The alleged victim, who had again run away from home while awaiting the hearing, was not pregnant. Judge Julian Houston postponed the hearing until June 9. When the trial resumed, Valdéz acknowledged he knew the girl but denied any sexual relations. Judge Houston moved that the case be decided by a Suffolk County Grand Jury, which met on July 13 and refused to indict Valdéz, citing lack of evidence.

“I feel like a new man,” Valdéz said, “I feel strong. I want to be in uniform tonight.”17 The strange and sorry chapter of Valdéz’s life was over, but so was his Red Sox career. He had been suspended pending the hearing; the previous Friday, the Red Sox had designated him for assignment. “I’m very happy for Julio,” said Red Sox GM Haywood Sullivan, “but he won’t be returning to the club. We’ve informed the other 25 major league clubs that he’s available and are waiting to hear from them.”18

No club signed him, so Valdéz was retained by Boston and sent to Double-A New Britain. It seemed like this was a step backwards, but it was more of a relief. In a feature on Valdéz for the Globe, Bob Duffy noted, “the team had given him employment instead of exile, and to Valdéz, the address didn’t matter so long as the job was the same.” And Valdéz never lost his smile, even after playing through a broken index finger he suffered after just a couple of games. He finally went on the disabled list. “He does not stop smiling,” Duffy wrote. “I just love to play baseball,” was Valdéz’s straightforward attitude. He was still employed in the game. “I don’t care if I’m in Pawtucket or New Britain or Winston-Salem,” he said. “I just want to play baseball.”19

Valdéz remained with New Britain to start the 1984 season. The organization told him they were seeking to trade him to provide a fresh start. His prospects looked bleak in Boston. Marty Barrett had taken over as the starting second baseman for Remy, who would soon retire. Shortstop was handled by Jackie Gutierrez, and veteran utility players Hoffman and Ed Jurak were reliable. In Pawtucket, Chico Walker and Steve Lyons were the next generation of utility players, and both could play the outfield, unlike Julio. “Maybe somebody will pick me up soon,” Valdéz hoped. “Right now, I just have to do the best I can.”20 Valdéz finished the year split equally between New Britain and Pawtucket, batting a combined .262.

Julio returned to the Dominican Republic to play winter ball for the Caimanes team. “People in The States sometimes don’t understand Dominican ballplayers,” he said. “[They] couldn’t understand what it’s like to be poor the way people here are poor.”21

Valdéz finally received a fresh opportunity in 1985 when he signed a minor-league contract with Iowa, the Triple-A club of the Chicago Cubs in the American Association. He batted .219 as the primary third baseman for Iowa that year, also playing a fair amount at short. He hit .237 in a utility role in 1986 and was solid defensively.

There was one last legal hurdle for Valdéz to clear. In 1983, the family of the alleged victim had filed a civil lawsuit against him, seeking $700,000 for damages related to emotional distress. The case was dismissed on August 4, 1986. The long ordeal was finally over. “I was just seeking justice,” Valdéz said. “All this time I maintained my faith in God that it would turn out this way.”22 Valdéz may have lost four seasons in the major leagues because of the allegation.

Valdéz played his last season in his homeland with Leones del Escogido in the winter of 1986-87, getting into 14 games. He’d also played with Escogido the previous winter after coming over from Azucareros del Este. Overall, in 303 games across nine Dominican seasons, Valdéz batted .251 with 6 homers and 91 RBIs. He was a reserve on two champion teams, both with Licey. The 1979-80 club was managed by Del Crandall; Manny Mota led the 1982-83 squad.

Valdéz lost much of the 1987 season, his last full year with Iowa, when he sustained a knee injury in late July. He played only 63 games and batted a career-high .276.23 In 1988, Valdéz, still recovering from the injury, was nonetheless invited to spring training. The Cubs’ new manager was Don Zimmer, who remembered Valdéz from a decade earlier and had kept an eye on his movement. Zimmer was looking for a backup to Shawon Dunston. It never panned out, however; Valdéz needed extra time rehabbing and stayed in extended spring training. The Cubs sent him to their affiliate in Pittsfield, Massachusetts of the Double-A Eastern League, where he played in only 25 games and batted under .200. He was promoted back to Iowa briefly after spending time at Class-A Winston Salem (now a Cubs’ affiliate) as player-coach.24

Valdéz’s playing career in the U.S. had concluded. He stayed within the Cubs organization, first as an instructor with the Wytheville (Virginia) affiliate in the Appalachian League in 1989. From the mid-1990s through the first two decades of the 21st century, Valdéz had stints as a manager of Dominican Summer League teams affiliated with major league clubs. From 1995-96 he managed the combined DSL Cubs/Padres club, from 1997-2001 the DSL Cubs, in 2008 the DSL Yankees, and from 2015-2018 the DSL White Sox.

In later years, Valdéz worked as a first-base coach and assistant manager with the Licey Tigers. Julio Valdéz died in Nizao on July 24, 2022 at the age of 66, after suffering from prostate cancer for several months. Valdéz left a widow, María del Carmen and six children.25 “Peace to your soul!” the Tigres del Licey Tweeted at his passing.26 “Good friend, always smiling, “a user Tweeted in remembrance of Valdéz. “May God have him in a place of peace.”27

Last revised: July 28, 2022 (zp)

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Nowlin and Rory Costello and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team. Thanks also to Cassidy Lent of the A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York, who provided a copy of Valdéz’s file and questionnaire.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com, winterballdata.com (Dominican statistics, available with subscription fee), and the following:

Arthur Jones, “Girl Charging Valdéz Rape, ‘Not Pregnant,’” Boston Herald, May 25, 1983: 16.

Betsy A. Lehman and Wendy Fox, “Red Sox Player is Arrested on Rape Charge,” Boston Globe, May 7, 1983: 17.

Beverly Ford, “Teen-age Accuser Cries, ‘Now Everyone Will Think I Lied,” Boston Herald, July 14, 1983: 4.

Elizabeth H. Holland, “Valdéz’ Accuser Flies the Coop,” Boston Herald, May 18, 1983: 4.

J.C. Kim, “Rape Case Idles Valdéz from the Red Sox,” Boston Herald, May, May 8, 1983: 7.

J.C. Kim and John McGinn, “Red Sox Player is Held on Rape Charge,” Boston Herald, May 7, 1983: 9.

Kevin Cullen, “Sox’ Valdéz Rape Case to go Before Grand Jury,” Boston Herald, June 10, 1983: 7.

“Valdéz Denies Rape,” Boston Herald, May 10, 1983: 13.

“Valdéz Pleads Innocent to Rape,” Boston Globe, May 10, 1983: 25.

William Cash, “Valdéz to Face Grand Jury for Alleged Rape of Teenager,” Boston Globe, June 10, 1983: 19.

Notes

1 Anne Raver, “Hometown Rallies Round Its Boy Julio,” Boston Herald, May 15, 1983: 13.

2 Raver’s 1983 article explored Julio’s family and homeland, where the unemployment rate was 40% and the average wage was $100 a month.

3 Raver, 12.

4 Leigh Montville, “Valdéz a Rare Sox Breed,” Boston Globe, August 14, 1981: 29.

5 Winterballdata.com shows the winter of 1978-79 as Valdéz’s first in the Dominican winter league. He may still have been playing at a lower level in his homeland before joining Licey. It’s also possible that he may have been with Licey but simply not have gotten into any games because the Tigres then had various established shortstops and second basemen.

6 Peter Gammons, “Joy to the Pitchers…Rico’s back,” Boston Globe, March 25, 1976: 23.

7 Associated Press, “Zimmer Likes Young Shortstop,” The Transcript (North Adams, Massachusetts), March 16, 1979: 15.

8 “Zimmer Likes Young Shortstop.”

9 Montville.

10 Joe Giuliotti, “Last Shot at Red Sox for Valdéz,” Boston Herald, March 30, 1982: 44.

11 “I May Be Pregnant—Valdéz Rape Teen,” Boston Herald, May 9, 1983: 7.

12 Margery Eagan, “The Strange Saga of Valdéz and Baseball ‘Nut,’” Boston Herald, May 10, 1983: 16.

13 Dennis “Oil Can” Boyd with Mike Shalin, They Call Me Oil Can: Baseball, Drugs, and Life on the Edge. (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2012), 171-172.

14 Joe Giuliotti, “Valdéz is Innocent Until Proven Guilty,” Boston Herald, May 10, 1983: 57

15 Joe Fitzgerald, “Paying the Price of Fame,” Boston Herald, May 10, 1983: 55.

16 Michael Madden, “Game is Just Starting,” Boston Globe, May 10, 1983: 60.

17 Diane Lewis and Stephanie Chavez, “Grand Jury Drops Rape Case Against Julio Valdéz,” Boston Globe, July 14, 1983: 15.

18 Joe Giuliotti, “Sullivan: Julio Through as Red Sox,” Boston Herald, July 14, 1983: 58.

19 Bob Duffy, “Valdéz Happy: just Being Active in Baseball Keeps Him Smiling These Days,” Boston Globe, August 30, 1983: 40.

20 Terese Karmel, “For Valdéz, It Is a Major Displeasure,” Hartford Courant, April 22, 1984: E-6.

21 Peter Gammons, “The Winter Game: Dominican Republic Has Made Baseball a Game for All Seasons,” Boston Globe, January 25, 1985: 62.

22 Diego Ribadeneira, “Jury Says Valdéz is Innocent,” Boston Globe, August 5, 1986: 17, 23.

23 Wayne Grett, “Walker’s Homer Boosts I-Cubs,” Des Moines Register, July 31, 1987: 3S.

24 Wayne Grett, “I-Cubs Collect Just 5 Hits in 3-2 Defeat,” Des Moines Register, August 9, 1988: 3S.

25 Martin Rosario, “Former Major League Baseball Player Julio Valdez Passed Away,” (translated from Spanish) Prensa Y Gente, July 26, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022. https://prensaygente.com/2022/07/26/fallecio-el-ex-pelotero-de-grandes-ligas-julio-valdez/

26 Tigres del Licey Tweet July 24, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022. https://twitter.com/TigresdelLicey/status/1551287518380920832 (translated from Spanish)

27 Tweet by username “Luismah.” Retrieved July 27, 2022. https://twitter.com/man66230876/status/1551921705605632000 (translated from Spanish)

Full Name

Julio Julian Castillo Valdez http://dev.sabr.org/?p=61695

Born

June 3, 1956 at San Cristobal, San Cristobal (D.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.