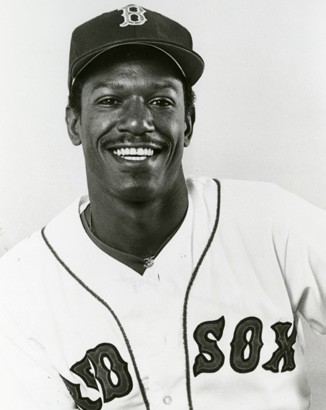

Oil Can Boyd

Dennis “Oil Can” Boyd starts his autobiography recalling back in 1964 when he was 5 years old, and his uncle Frank Boyd brought three civil-rights workers by the family home. Later that same year, James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner were discovered murdered. Dennis believes they were killed just after they left the Boyd home to head for Memphis.1

The home was in Meridian, Mississippi, where he had been born on October 6, 1959, to parents known as Skeeter and Sweetie. Skeeter was Willie James Boyd and Sweetie was his wife, Girtharee (McCoy) Boyd. Willie Boyd worked in Meridian as a landscaper and Peter Gammons, in the speech he gave on being honored with the J.G. Taylor Spink Award at the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2005, recounted a 1985 meeting with Mr. Boyd, who himself said he was literally “landscaping the yard of the grand dragon of the Ku Klux Klan” when he saw the cars heading out “to take care” of the three civil-rights workers. Then Mr. Boyd looked at Gammons and talked about the Klansman: “Today that man is destitute and crippled with arthritis, and my boy, Dennis Boyd, is pitching in the major leagues for the Boston Red Sox.”2

That he was. Dennis won 15 games that year, and in 1986 pitched in the World Series. Willie Boyd himself had been a baseball player, as had his father before him. And Willie’s work in Meridian included maintaining the baseball field in town.

Dennis was African American, but he also had Choctaw lineage on his father’s side, and his great-grandfather on his mother’s side was “as white as snow.”3 It was a complicated heritage, one great-grandfather Irish and another a slave.

The Boyd family also had a baseball pedigree. As Boyd himself said, “My father played just a little bit of a while in Negro League baseball. My two uncles played. K.T. Boyd, my dad’s brother – Kansas City Monarchs. And Robert Boyd – he played for the Kansas City Athletics but he also came out of Negro League baseball. He played for the Memphis Red Sox.

“And my great-great-uncle played, Benjamin Boyd. He played for the Memphis Red Sox and the Homestead Grays.”4

Robert Boyd – Bob Boyd – was the first African American to sign with the Chicago White Sox, in 1950, and broke in with them the following year. He played for the Orioles, Kansas City, and Milwaukee over parts of nine seasons.

With [at least] five older brothers, Dennis played a lot of baseball and often with boys older than him. Dennis even played in games himself with former Negro Leaguer Early Moore. Three houses away from the Boyds lived former Negro League pitcher Roy Dawson.5

Family ties didn’t end there. “I’ve had a few cousins, too – Barry Larkin. My dad’s first cousin. Troy Boyd played for the Chicago Cubs and San Diego Padres. And in minor-league baseball, Brian Cole and Popeye Cole – Robert Cole. Brian Cole is the one that Sports Illustrated did an article on two years ago. He got killed. He was in the Mets organization. Bob Stanley coached him in the minor leagues. He got killed in 2001 in a car accident coming from spring training. It was called ‘The Best Player You Never Saw.’6 Albert Pujols and a lot of them made comments about him. They saw him in the minor leagues and they didn’t believe what they was seeing.”7

Dennis played ball in Meridian; in 1972, he was named MVP of the little league all-star game held in Hattiesburg.8 The next year – 1973 – two of his brothers were drafted, Mike by the Dodgers (he was a pitcher and his team had won the Mississippi state championship, but he was never offered a contract because of the negativity coming from his getting a white girl pregnant), and Don by the Cardinals. A 15th-round pick, he was a second baseman who played one season at rookie ball in the Gulf Coast League.

Dennis was fortunate to have a high-school coach, Bill Marchant, who taught him baseball strategy, the mental side of the game. As a white man coaching an integrated team in Mississippi at the time, Boyd wrote, Marchant “could have been killed … not harmed, not threatened, but literally killed for putting my brothers on the team.”9 It was Marchant who bought spikes for Dennis and his brother Neal. The Meridian team went on to the state playoffs, and Dennis got a scholarship to Jackson State University, where he was coached by Robert Braddy. He said his record at Jackson State was 20-5 and he’s in the school’s hall of fame. The Boston Red Sox drafted Dennis Boyd in the 16th round of the 1980 draft and he was signed by Red Sox scout Ed Scott.

Boyd was assigned to Elmira in the New York-Penn League and was 7-1 in 1980 with a 2.48 earned-run average. In 1981 he pitched in Class A for the Winter Haven Red Sox of the Florida State League and was 14-8 (3.63). That winter he went to Colombia to play some winter ball and, he writes, was first introduced to cocaine.10

Boyd advanced to Double A in 1982, pitching in Connecticut for the Eastern League’s Bristol Red Sox, and recorded an identical 14-8 mark, but with an improved 2.81 ERA even at the higher level of play. He was dubbed “the hottest pitching prospect in the Red Sox farm system.”11 An Associated Press story at the end of August explained his nickname, dating it back to high-school days when he would drink beer with his friends: “They called it ‘oil’ then, and Boyd sure could put away a few cans.”12 His 191 strikeouts (in 205 innings) led the Eastern League. At the very end of the 1982 season, Boyd was a September call-up and was given a look at the majors, debuting at Fenway Park with a start against the Cleveland Indians on September 13. He gave up one run in the first inning and one more in the fourth, but that was enough to cost him the game. He worked 5⅓ innings, giving up just the two runs, but the Red Sox offense scored only one run, in the bottom of the ninth, and lost the game, 3-1.

Manager Ralph Houk used Boyd twice more in relief, both times against the Yankees, and he gave up three more runs in three innings of work. But he’d gotten his feet wet. He’d made the big leagues.

The 1983 season was spent in Triple-A with Pawtucket, with a couple of call-ups to Boston, once in June and then again at the beginning of August. Boyd picked up his first major-league win, against Minnesota, on June 3 and worked a total of 98⅔ innings in 15 games, 13 of them starts. His best outing was a September 2 complete-game 5-1 win over the White Sox. His record for the season was 4-8, but he had a solid 3.28 ERA.

Part of 1984 was also spent in Pawtucket, after he’d begun the season 0-3 (with a 7.36 ERA) for Boston and had an argument with Houk that resulted in his being sent back down, though Houk was generous in his praise of Boyd at the time and the argument could be made that he’d been “much too easy” on the young pitcher.13 After spending a month back in Triple-A, Boyd was summoned back to the Red Sox and won 12 games for a 12-12 season with an overall 4.37 ERA. He spent the full 1985 and 1986 seasons with the big-league club, working both seasons under new manager John McNamara. Boyd won a club-leading 15 games in ’85 with 13 losses and won 16 games in ’86, against 10 losses. He worked 13 complete games in 1985 and 10 in 1986. The game Oil Can thought was his best was the June 19, 1986, complete-game three-hit shutout he pitched against the Orioles at Memorial Stadium, working with Dave Sax behind the plate.14

The Red Sox won the pennant and went to the seventh game of the World Series in 1986. Boyd’s 16 wins were second only to Roger Clemens, whose 24-4 record won him both the Cy Young Award and the American League MVP. Bruce Hurst was 13-8 (2.99).

Boyd was a right-hander, standing 6-feet-1 and listed at a lean and wiry 155 pounds. He pitched the pennant-clinching game, a 12-3 complete-game win over the Toronto Blue Jays on September 28. When it came to the postseason, Clemens was hammered by the Angels’ offense in the first game of the ALCS, giving up eight runs (seven earned) in 7⅓ innings. The Red Sox lost, 9-1. Hurst won Game Two, a complete-game 9-2 win. Just one of California’s runs was earned. Boyd pitched Game Three, in Anaheim, and the two teams were tied, 1-1, after six, the Angels having scored once that inning. After getting two outs in the bottom of the seventh, however, Boyd gave up a solo home run to Dick Schofield, a single to Bob Boone, and a two-run homer to Gary Pettis. McNamara pulled his pitcher, but the damage was done, and Boyd took a 5-3 loss. After Dave Henderson‘s heroics saved the Red Sox from elimination in Game Five, Boyd was the starting pitcher in Game Six back home in Boston. He worked seven full innings, giving up three runs, and left with a comfortable 10-3 lead that wound up a win.

After Boston won World Series Games One and Two at Shea Stadium, Oil Can Boyd was asked to start Game Three at Fenway. It didn’t go well. Leadoff batter Lenny Dykstra homered. Two singles and a Gary Carter double produced a second run and saw runners on second and third with still not an out. With one out, Danny Heep singled in two more. It was 4-0 Mets before the Red Sox came to bat. Boyd worked seven innings, giving up only two more runs over the next six, but Boston scored just one run all evening. The way it worked out, he wasn’t called upon to pitch again at any point in the remaining four games. Naturally, like any competitive athlete, he wished he’d been given the opportunity. He didn’t think the Mets would be able to beat him twice in a row. “We had an opportunity to win Game Seven. I pitched very well in Game Three; after the first inning, I pitched overly well. If I came out with that same momentum, knowing the hitters like I did, facing the same guys … no, no, no. I’ve got too good a stuff. I’m too good a pitcher. I can’t see myself giving up more than two or three runs and getting into the seventh or eighth inning, no question.”15

Though 1985 and 1986 were his best seasons, “Can” (as he was called) acknowledges he had a serious problem with cocaine. He was hospitalized before the ’86 campaign began. “I had the whole cover story about hepatitis,” he wrote, “but it was flat-out me smoking crack every damn day. I was smoking cocaine, freebasing, doing crack; they had all kind of names for it back then. But whatever you call it, that’s what I was doing.”16 Helping counsel him through this was team physician and co-owner Dr. Arthur Pappas. “He was almost like a father figure to me at that time.”17

Because he had pitched so well both in 1985 and 1986, Boyd felt he should have been selected for the All-Star Game. He took being passed over the first time, but in 1986 when he clearly was having an exceptional year and was second in the league in victories, he snapped at what he took as a snub (Mike Boddicker had the same number of wins as Boyd and was also passed over) – and Boyd bolted. He quit the team. It didn’t go over well with him teammates; Don Baylor said, “No one player is bigger than the team.”18 It also wasn’t the first time his volatile behavior had resulted in disciplinary action; he’d been fined a day’s pay after an August 21 loss to the Texas Rangers and a locker-room run-in with Jim Rice.19 In spring training 1987, he’d “exploded” at a writer who questioned him regarding videotapes he had not returned; that became known as “Can’s Film Festival.”20

This time Boyd was suspended for 21 days but eventually came back in early August. While he was out, though, he had gotten into a tussle with some police and his arm had gotten wrenched. He says he never fully recovered. Indeed, though one wouldn’t know looking at his pitching record, he was pitching in pain and subpar for the rest of the season and into 1987. He said he didn’t give up even one run in spring training 1987, but the pain remained. He was able to pitch in only seven games all year, until surgery in August when it was discovered he had a hairline fracture.

The problem finally fixed, Boyd was able to start 23 games in 1988 (9-7, with a 5.34 ERA) but though the Red Sox reached the postseason once more, Boyd had developed blood clots and wasn’t able to pitch after August 26. He started the 1989 season with the Red Sox but had an even poorer start and from the beginning of May to the start of September, all he could manage was to get into three games in the minors for a total of 12 innings.

After becoming a free agent, Boyd signed with the Montreal Expos in early December 1989, and he enjoyed his time with the Expos: “It was the best time I ever had playing baseball.”21 And he had a very good year in 1990, 31 starts and a 2.93 earned-run average – the best of his career. His record was 10-6, reflecting the fact that many of the games were resolved in the late innings. He pitched most of the 1991 season with Montreal, his 3.52 ERA not reflected in his 6-8 record, but he was traded to the Texas Rangers on July 21, for three players. He took it personally that he’d been traded, an indication to him that the Expos didn’t want him.22 Texas didn’t suit Boyd at all and it showed in his work, 2-7 with a 6.68 ERA the rest of the season.

As it happened, Oil Can never got back to the big leagues. His final stats show him 78-77 with a 4.04 ERA over 10 seasons in the majors.

The Pirates organization signed Boyd to a minor-league contract for 1992, but he came to understand that as somewhat of a difficult personality, “I knew I’d been blackballed out of the game.”23 When Indians manager Mike Hargrove gave him a look in the spring of 1994, Boyd quotes him as saying, “If it was my choice and I was in control of this, you would be in my rotation. You wouldn’t just be on my pitching staff, you’d be in my five-man rotation. But your personality is bigger than your right arm.”24

In 1993 Boyd played in the Mexican League for Industriales of Monterrey (at one point earning 11 consecutive saves in 11 consecutive days), and in the first part of 1994 he pitched for the Yucatán Leones. He finished the year with the Sioux City Explorers in the independent Northern League, where pitched again in 1995. There were occasional problems that cropped up off the field, but Boyd played some independent ball in Maine and Massachusetts, in 1996 and 1997.

He also tried to become a developer in Meridian that year, building homes on spec, but lost it all when none of the black families who were interested could get financing from local banks. When he moved back north to rejoin his wife and family, a woman he’d been seeing in Meridian was upset and said she was going to burn his things. He responded heatedly, and she recorded the conversations. “I threatened to beat her ass if she burned my stuff.”25 It was the kind of thing people might understandably say in what they thought was private. Boyd’s words, uttered across state lines, led to his arrest by the FBI. After some twists and turns, he wound up in the Fort Dix Federal Penitentiary for 120 days.

At age 45, Can pitched again, in 2005, in the independent Canadian-American League for the Brockton Rox. He worked in 17 games and was 4-5 with a 3.83 ERA.

The year 2005 was, as Boyd puts it, “my last year of professional baseball.” He’s kept busy since then, living in East Providence, Rhode Island. “I’ve been doing a lot teaching up here. A lot of lessons from the beginning of January through May. I got a book out. I’m working on a minor-league baseball project down in Mississippi, to bring minor-league baseball to my hometown of Meridian, Mississippi. It’s a project I started on years ago but it’s finally in the last stages of actually materializing in the next year or so. And I’m getting ready to do a reality TV show. It’s called Second Chance. They’re going to do 12 episodes, over 24 months.

“I do a lot of charity things. I do a lot of stuff with the Red Sox over the summer. Some cameo appearances, motivating speaking, autograph signing.”26

Boyd has two children – Dennis, and his daughter Tala – in their 20s as of this writing in 2015. “And I’m a granddad. Looking forward to that part of my life, too.”

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also consulted the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Dennis “Oil Can” Boyd with Mike Shalin, They Call Me Oil Can (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2012), 9-11. Chaney was a native of Meridian and a “close friend” of Frank Boyd. See p. 13.

2 Ibid., v.

3 Ibid., 16.

4 Author interview with Dennis Boyd, January 6, 2015.

5 They Call Me Oil Can, 27.

6 Sports Illustrated, April 1, 2013.

7 Author interview with Dennis Boyd, January 6, 2015.

8 Photograph and caption in the photo insert in They Call Me Oil Can.

9 Ibid., 46, 47.

10 In his autobiography, Boyd devotes a full chapter to cocaine and its effect on him. See Ibid., 59-74.

11 Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican, August 14, 1982.

12 Boston Herald, August 29, 1982.

13 Boston Herald, May 20, 1984. The assessment was Joe Giuliotti’s.

14 Boyd, They Call Me Oil Can, 136.

15 Author interview with Dennis Boyd, January 6, 2015.

16 In the Boston Globe, March 13, 1986, Pappas explained Boyd’s prolonged illness and six-day hospital stay as due to a noncontagious form of hepatitis.” In They Call Me Oil Can, Boyd told about the time he was pitching in Oakland and had a few rocks of crack in his baseball cap, which scattered on the mound when his cap flew off of his head after one energetic pitch. See page 71.

17 Ibid., 70.

18 Boston Globe, July 11, 1986.

19 “Boyd, Rice in clubhouse tiff,” Boston Herald, August 22, 1985.

20 Boston Globe, February 28, 1989.

21 Boyd, They Call Me Oil Can, 89.

22 Ibid., 90-91.

23 Ibid., 95.

24 Ibid., 97.

25 Ibid., 117. The story of his experiences as a developer is on pages 112ff.

26 Author interview with Dennis Boyd, January 6, 2015.

Full Name

Dennis Ray Boyd

Born

October 6, 1959 at Meridian, MS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.