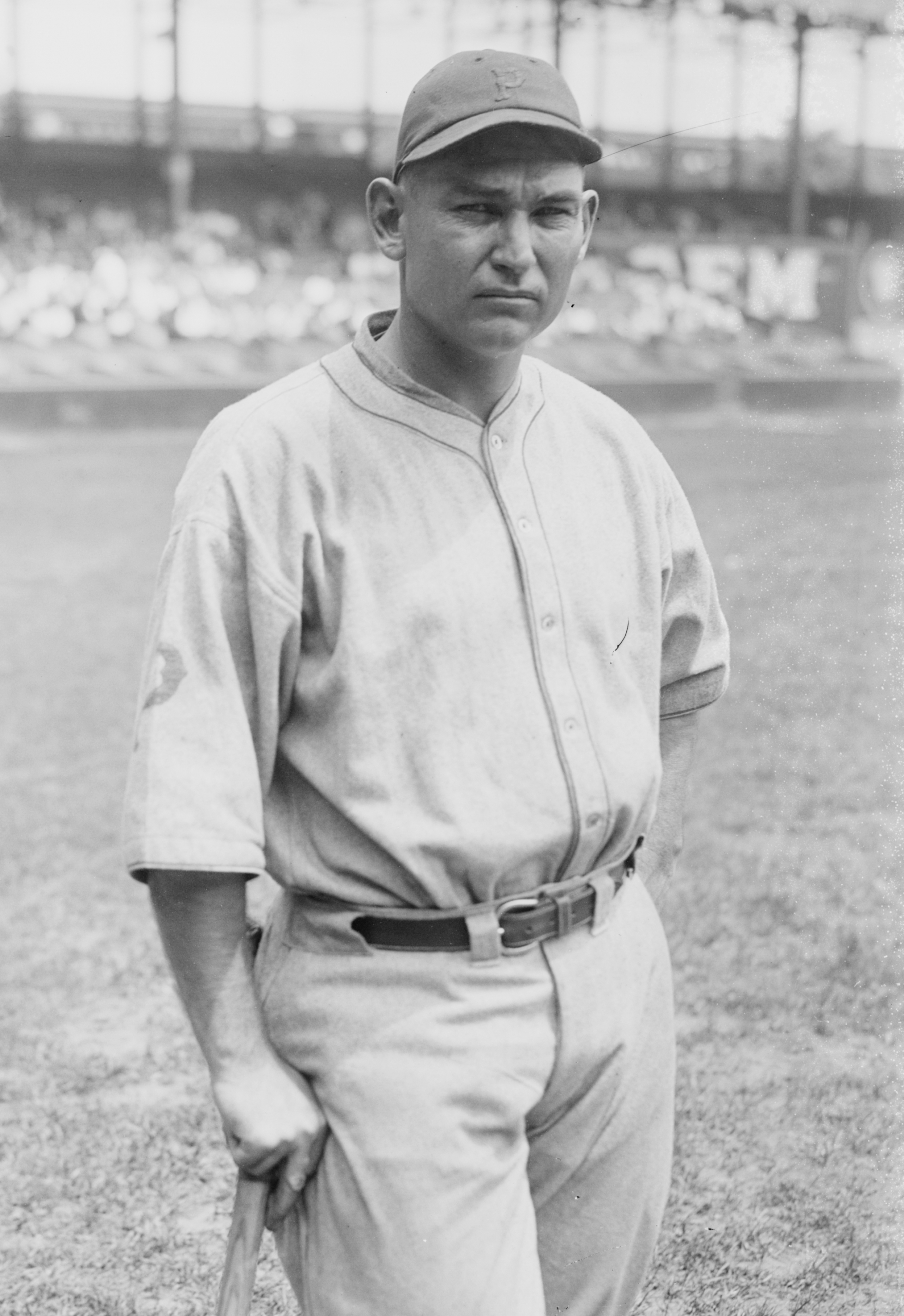

Reb Russell

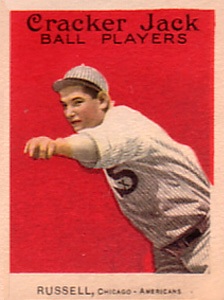

With superb control and a rising fastball, left-hander Reb Russell rose to stardom with one of the best rookie pitching performances of the Deadball Era, notching 22 victories and tossing eight shutouts for the Chicago White Sox in 1913. A typical Russell start featured few walks, few strikeouts, few runs, and many balls hit in the air as popups to the infielders or soft flies to the outfielders. “Russell gets out of a lot of tight places on his nerve,” White Sox manager Jimmy Callahan said. “Three men on the bases, with none out, is a situation that fails to shake him. In fact, it is in the pinches that he shows to advantage.”1

With superb control and a rising fastball, left-hander Reb Russell rose to stardom with one of the best rookie pitching performances of the Deadball Era, notching 22 victories and tossing eight shutouts for the Chicago White Sox in 1913. A typical Russell start featured few walks, few strikeouts, few runs, and many balls hit in the air as popups to the infielders or soft flies to the outfielders. “Russell gets out of a lot of tight places on his nerve,” White Sox manager Jimmy Callahan said. “Three men on the bases, with none out, is a situation that fails to shake him. In fact, it is in the pinches that he shows to advantage.”1

After an arm injury cut short his pitching career, Russell returned to the big leagues in 1922 as a slugging outfielder with the Pittsburgh Pirates in another impressive “debut” season. Although he was a bit naïve when he entered the big leagues, Russell’s eagerness to learn and his calm demeanor helped him to polish his rough edges both on and off the field. By 1915 the pitcher who had once been a major source of inspiration for Ring Lardner’s self-centered pitcher Jack Keefe of You Know Me, Al fame had become a mainstay of high society, discussing music, literature, and psychology.

Ewell Albert Russell was born on March 12, 1889, on a farm near Albany, Mississippi, the second of three children of Tobias and Naomi Russell. When he was one year old, his family moved to Texas and eventually settled on a 100-acre farm eight miles outside Bonham, an agricultural center of 5,000 people in north Texas and a key stop on the Texas and Pacific Railroad. Although Russell attended primary school and helped his father on the farm, he developed a passionate love of baseball and could often be found ignoring his chores while playing ball on a crude diamond in the nearby town of Telephone. When he was 15 he left the farm for good and got a job driving teams for the railroad.

In May 1912 Russell signed to pitch for Bonham of the Texas-Oklahoma League at a salary of $75 a month. Despite using “nothing but curves,” he impressed scouts by striking out many while walking few.2 After his success in Bonham, Russell’s contract was purchased by the Fort Worth Panthers of the Texas League. At Fort Worth a line drive off his thumb removed the curveball from his arsenal and he had to rely on his fastball and changeup. While posting a 4-4 record in 13 games for the seventh-place Panthers, Russell was spotted by White Sox scout and former major-league pitcher Harry Howell, who liked what he saw and recommended the young pitcher to owner Charles Comiskey. After the 1912 season, the White Sox drafted Russell for $1,200.

The 5-foot-11, 185-pound Russell arrived at camp in the spring of 1913 with great speed, exceptional control, confidence, coolness under pressure, and a willingness to learn. He also arrived with barely any money in his pocket and little knowledge of major-league hitters. Although he had success early in camp based strictly on his fastball, coach Kid Gleason helped him to return the curveball to his arsenal by showing him a new grip, which generated a sharp break. The White Sox initially intended to farm Russell out to the Pacific Coast League for more seasoning, but Gleason successfully argued against it and, to the surprise of many, Russell made the club.3

On April 18, 1913, Russell made his major-league debut and justified Gleason’s confidence in dazzling style. With the White Sox trailing Cleveland 4-0, Russell was inserted in the seventh inning and proceeded to retire nine of the 10 batters he faced, including five strikeouts. His fine performance earned him a spot in the starting rotation, where he quickly blossomed into one of the league’s best pitchers. “That boy has everything,” Callahan marveled. “He has speed, he has curves, he has control, he has nerve, he has strength. What more could I ask for?”4

Russell, now called Reb or Tex by the papers, finished the season with 22 wins, a 1.90 ERA, and a league-leading 52 games pitched. He ranked second in the American League with 316⅔ innings pitched, and his eight shutouts tied the major-league rookie record established by Russ Ford three years earlier. Demonstrating a knack for winning close games, Russell won five by the score of 1-0. Displaying the first glimpse of his hitting skills, Russell also connected for three triples during the season, and hit his first major-league home run on June 16, against the Washington Senators.

After the season, on October 14, Russell married Charlotte Benz, a cousin of his White Sox roommate Joe Benz, and relocated to her hometown of Indianapolis. He did not join his White Sox teammates on the world tour organized by Charles Comiskey and John McGraw, but he did participate in an exhibition game with them in Bonham, Texas, in which he was presented with a gold watch and got a rousing ovation.5

On May 26, 1914, Russell was in the midst of a shutout when he collided with Yankee first baseman Les Nunamaker while attempting to get on base. The collision resulted in injuries to his left ankle and hip and kept him out of action for three days. Upon his return to the mound, Russell was no longer effective and was hit hard. The combination of the injury and an increase in his weight led to a loss of velocity on his fastball and a loss of break on his curve. By the end of the season, in which his ERA rose a full run to 2.90, doubts arose as to whether Russell would ever be effective again.

Russell reported to spring training in 1915 grossly overweight and new White Sox manager Pants Rowland threatened to cut him from the team. Under Rowland’s direction, Reb underwent an intensive program of hot mud baths and extensive workouts in an attempt to reduce weight. He also immediately went on a diet consisting solely of lettuce with French dressing, side orders of lemon ice, and pickles.6 By early March he had dropped nearly 40 pounds and was back near his playing weight. By mid-March, he had regained his form and Sam Weller reported in the Chicago Tribune that “Russell let loose more speed than he has shown in a year and his curve ball, which disappeared so mysteriously last season, was seen to crack sharply across the plate several times.”7 His job was safe. Splitting his duties between the starting rotation and the bullpen, Reb turned in a fine season, winning 11 games and pitching three shutouts.

In 1916 Reb reported to camp already in shape and so impressed Rowland that he was chosen as the club’s Opening Day starter against Detroit. After getting shelled by the Tigers, he was relegated to relief duties, where he regained his manager’s confidence by contributing a number of solid outings. He spent the rest of the season shuffling between the rotation and bullpen, and was the workhorse of the staff, leading the team in innings pitched (264⅓) and victories (18) while posting a 2.42 ERA. Russell also led the league with the fewest walks per nine innings pitched, as he allowed just 42 free passes. A turbulent four years into his big-league career, many observers still considered Russell to be the best left-handed pitcher in baseball next to Babe Ruth.

Such comparisons did not stand up for long. Russell’s first attempts to throw a curveball in the spring of 1917 left him unable to straighten his left arm. X-rays revealed the presence of “two fibrous growths in Reb’s left arm just above the elbow.”8 To combat this malady, the doctor prescribed “exercise and heavy lifting.”

Such comparisons did not stand up for long. Russell’s first attempts to throw a curveball in the spring of 1917 left him unable to straighten his left arm. X-rays revealed the presence of “two fibrous growths in Reb’s left arm just above the elbow.”8 To combat this malady, the doctor prescribed “exercise and heavy lifting.”

Once again Russell spent the year going back and forth between the bullpen and the starting rotation. With the White Sox in the midst of a tight pennant race against defending champion Boston, Reb pitched some of the best games of his career. In August he won several important games for Chicago, including two shutouts against the Red Sox. He finished the year with a 15-5 record and a sparkling 1.95 ERA and once again led the league with the fewest walks per innings pitched. Nevertheless, the arm injury took its toll and the White Sox could never be sure about whether he’d be able to pitch on a given day. Russell’s one start in that year’s World Series was a disaster; he failed to get a single out before being removed from the game. “Opposing batters haven’t the least respect for a man with a bum arm,” he wrote afterward in a column for Baseball Magazine. “Still … it is something to be a member of the greatest club in the world, even if you couldn’t contribute your share to that end.”9

Russell didn’t sign his 1918 contract until early April, and was used sparingly during the first two months of the season. Back in the starting rotation by mid-June, he was not as effective as he had been in previous years, displaying uncharacteristic wildness and often losing his effectiveness late in games. Starting 15 games, he finished the year 7-5 with a 2.60 ERA.

In 1919 Russell was not impressive in spring training and barely made the team. After facing two Red Sox batters and not recording an out in his only outing, on June 13, Reb was removed for good. Released to Minneapolis of the American Association, he finished the year playing center field, and hit nine home runs, more than twice as many as anyone else on the team. He was not with the White Sox during the tainted World Series against the Cincinnati Reds.

In 1920 Russell attempted one last comeback as a pitcher with the White Sox but could not make the team. He returned home to Indianapolis, where he found work in a garage as an auto assembler. Later that season the Minneapolis Millers traveled to Indianapolis and were in emergency need of an outfielder. Reb agreed to fill in and he came through with a couple of hits in the game. The Millers signed him and he went on to have a great season at the plate, hitting .339 with six home runs and 41 RBIs in 85 games. He did even better in 1921, leading the Millers in batting (.368), home runs (33), and RBIs (132), while also posting a 1.64 ERA in five games on the mound.10

After clouting 17 homers for the Millers in his first 77 games of 1922, Russell was picked up by the Pittsburgh Pirates in July 1922. As part of a right-field platoon with Clyde Barnhart, he rapidly became one of the most feared hitters in the National League and finished the season with 12 home runs, 75 RBIs, and a .368 average in 60 games. The next year he failed to follow up on his sensational 1922 campaign, but still turned in a solid hitting performance, batting .289 with 9 home runs and 58 RBIs in 94 games. Given his limited defensive abilities, this performance was not enough to hold his spot in the starting lineup, and by the end of July Russell was benched. He finished the season with the team, but received scant playing time in the last two months.

After being released by the Pirates, Russell returned to the American Association, where he emerged as one of the league’s best hitters. With Columbus in 1924 and ’25, he smashed 55 home runs and drove in 247 runs while splitting time between the outfield and first base. From 1926 to 1929 he played for Indianapolis, winning a batting title in 1927 at .385. Released by Indianapolis in 1929, Russell finished out his minor-league career with Quincy (Illinois) of the Three-I League, and Mobile and Chattanooga of the Southern League. His lifetime minor-league batting average was .323.

When his minor-league career ended, Reb got a job as a security guard at the Kingan and Company meat-packing plant in Indianapolis and worked there until he retired in 1959. During that time he played for a number of local semipro teams including the Sterling Beers, which were managed by Clyde Hoffa, a relative of labor leader Jimmy Hoffa.

Russell died at the age of 84 on September 30, 1973, two weeks short of his 60th wedding anniversary, in an Indianapolis nursing home, and was buried in St. Joseph Cemetery in Indianapolis. He was survived by his wife and two children.

An updated version of this biography appeared in “Scandal on the South Side: The 1919 Chicago White Sox” (SABR, 2015). This biography originally appeared in “Deadball Stars of the American League” (Potomac Books, 2006).

Sources

Chicago Tribune

Indianapolis Star

New York Times

Baseball Magazine

Hilton, George W., ed., The Annotated Baseball Stories of Ring W. Lardner 1914-1919 (Palo Alto, California: Stanford University Press, 1995).

Debano, Paul, The Indianapolis ABCs: History of a Premier Team in the Negro Leagues (Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarland & Co., 1997).

Davids, L. Robert, ed., Minor League Baseball Stars, Volume III (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1992).

Census of the United States, 1900, United States Bureau of the Census.

Census of the United States, 1920, United States Bureau of the Census.

Responses to Questionnaire from Hall of Fame by Ewell Albert Russell.

Retrosheet.org.

January 15, 1965, letter to Lee Allen from Ewell Albert Russell.

Notes

1 Washington Post, July 8, 1913.

2 Chicago Tribune, June 1, 1913.

3 Ibid.

4 Washington Post, July 8, 1913.

5 Frank McGlynn, “Striking Scenes From the Tour Around the World,” Baseball Magazine, August 1914.

6 Chicago Tribune, March 14, 1915.

7 Chicago Tribune, March 18, 1915.

8 Chicago Tribune, March 27, 1917.

9 Reb Russell, “How I Got My Chance,” Baseball Magazine, December 1917.

10 The Sporting News, January 5, 1922.

Full Name

Ewell Albert Russell http://dev.sabr.org/?p=61695

Born

March 12, 1889 at Jackson, MS (USA)

Died

September 30, 1973 at http://dev.sabr.org/?post_type=event&p=17245, IN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.