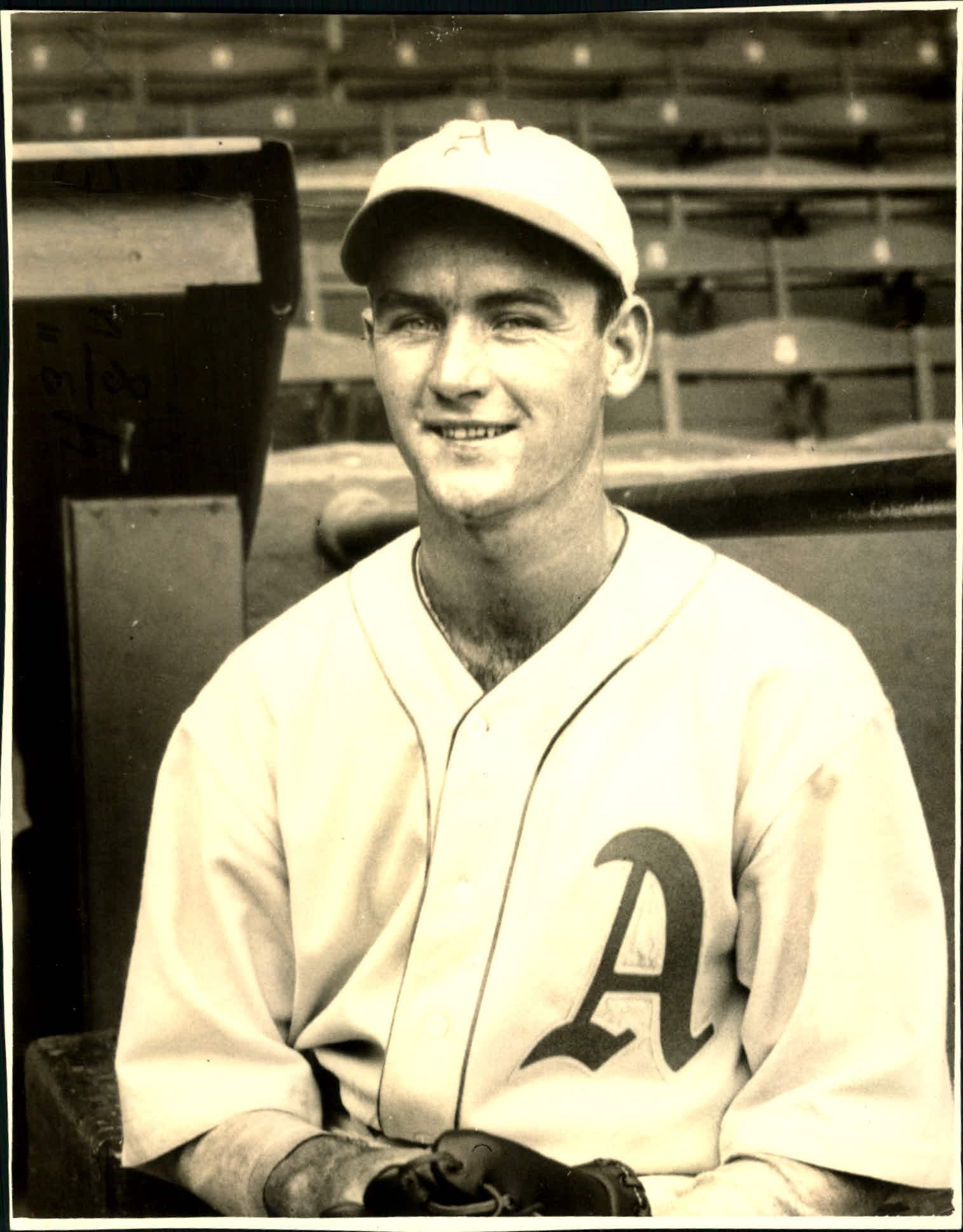

George Turbeville

George Turbeville pitched with the Philadelphia Athletics from 1935 to 1937. His best game performance came against the Cleveland Indians. He held them scoreless for 14 innings before losing on Earl Averill’s home run. Surrendering home runs is what Turbeville is best known for. He gave up Joe DiMaggio’s first major-league blast on May 10, 1936. He surrendered a grand slam to Tony Lazzeri in the second inning on May 24, 1936. Lazzeri hit a second record-tying grand slam in the fifth off Herman Fink. Yet Turbeville was not a gopher-ball pitcher compared to his contemporaries. The American League average over his career was about 0.6 home runs for every nine innings. Turbeville’s average was slightly under 0.5.

George Turbeville pitched with the Philadelphia Athletics from 1935 to 1937. His best game performance came against the Cleveland Indians. He held them scoreless for 14 innings before losing on Earl Averill’s home run. Surrendering home runs is what Turbeville is best known for. He gave up Joe DiMaggio’s first major-league blast on May 10, 1936. He surrendered a grand slam to Tony Lazzeri in the second inning on May 24, 1936. Lazzeri hit a second record-tying grand slam in the fifth off Herman Fink. Yet Turbeville was not a gopher-ball pitcher compared to his contemporaries. The American League average over his career was about 0.6 home runs for every nine innings. Turbeville’s average was slightly under 0.5.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, French Protestants known as Huguenots were persecuted and driven from the country by the monarchy and the Catholic Church. Many came to America, including the Turbeville family. In 1840 two Turbeville brothers founded a town in central South Carolina that would eventually bear their family’s name.1

Turbeville lies in Clarendon County, which was the scene of many of Francis Marion’s exploits during the Revolutionary War. The Turbevilles established a dry-goods store in the town that survived from the mid-nineteenth century until the Depression. George Turbeville was the sixth of 12 children born to James Martin and Annie Olivia (Evans) Turbeville. Born on August 24, 1914, he would eventually have six sisters and four brothers. James Turbeville fed the large clan by farming and working in the dry-goods store. Later in life he became a car salesman. Annie Turbeville died on January 18, 1930. James remarried, adding two stepsisters and three stepbrothers to the family.2

Turbeville attended school in his hometown. He grew to be 6-feet, 1-inch tall and weighed between 165 and 175 pounds.3 He threw and batted right-handed, but he claimed to be ambidextrous. Turbeville told reporters that he could actually throw farther as a lefty. He developed into a fine baseball player and led his high-school team as a pitcher and outfielder. He may have played with his brother James for a season, but the other Turbevilles in the lineup were not siblings.

As a pitcher, George had an overpowering fastball. In high school in 1933, it was the only pitch he needed to throw a one-hitter with 19 strikeouts against Hillcrest and to strike out 17 versus Elloree. He won that game with a triple that drove in Elbert Turbeville (likely a cousin). He faced Elloree again in the District 6 title game and struck out 22 in the two-hitter. This time he lost 4-2 because he issued seven walks and hit a batter. His catcher also made two throwing errors that plated runs.4

Turbeville had spent the summers playing baseball and had made a name for himself at the American Legion Junior level. He garnered some unwanted headlines in the summer of 1933. The Legion team in Elloree recognized his talent and added him to its roster. This was in violation of the league rules concerning jurisdictions/territory for a team. A player was supposed to be “a (bona fide) resident” of the community he played with. Turbeville was 35 miles from Elloree and to travel from one town to the other, he had to pass by seven other Legion Posts, three of which fielded teams.5

Understandably, George was ruled ineligible. Elloree’s other pitcher, John Haigler, was from their town. However, under scrutiny it was found that Haigler was over age. He also was ruled ineligible and the Elloree team dropped out of the running.

Undeterred, Turbeville found plenty of teams to play with outside the Legion system. That fall he attended Presbyterian Junior College in Maxton, South Carolina.6 That spring and summer, George was a busy ballplayer. He played in at least three leagues spread out over the central and eastern parts of the state. He was spotted pitching for Marion in the independent Interstate League by Philadelphia Athletics scout Ira Thomas. Thomas arranged a tryout at Shibe Park. Turbeville impressed Connie Mack, but not enough to be signed on the spot.7

Turbeville enrolled for a year at North Carolina University, but did not play baseball. He did take French classes to learn the language. Despite their heritage, his family had long ago shed their French customs, including the language.8 In the spring Turbeville played for Angier in the Durham City League and applied for admission to the Columbia City League but was denied. He was contacted by the Athletics and joined them in July.

The A’s had placed fifth in 1934. When he joined the team, it was in sixth place; the A’s fell into the cellar in early September and would never escape. After the 1935 season, Mack sent slugger Jimmie Foxx to the Boston Red Sox and pocketed $150,000.

Turbeville came to the majors without any minor-league coaching. He relied on his fastball and did not have an effective curve or changeup Over the years, Turbeville improved his pitch selection but he was never able to master his control.

Turbeville made his major-league debut a month shy of his 21st birthday. With the A’s at home and down 15-3 to Cleveland, George was sent to the hill on July 20 to pitch the ninth inning. He walked a batter and gave up a single to Hal Trosky before closing out the game. The Cleveland paper said, “he is a well-built right hander with fine action and a great fastball. … He may be worth watching.”9 Turbeville repeated the performance the next day. Again, Trosky got a single, but Turbeville retired the other three hitters.

The next day the White Sox came to town and Mack again sent Turbeville in for the ninth inning. This time his control failed him; he walked three and gave up three hits leading to five runs in a third of an inning. He pitched only 1⅓ innings in the next three weeks as the A’s coaching staff worked diligently with him.

On August 11, in the second game of a Sunday twin bill in Yankee Stadium, Turbeville got his first start. In front of a crowd of 22,000, he issued three walks in the first inning but escaped scoreless. In the second he issued two passes, but no hits. In the third he walked two and gave up a single to load the bases with one out. Rabbit Warstler misplayed a grounder from Bill Dickey and two runs scored. Roy Mahaffey relieved and earned the 5-4 win.

Turbeville’s next start came on August 24 in Cleveland. His ERA stood at 9.82 when he took the hill at League Park. The game went 15 innings and ended with Averill’s home run for a 2-0 Tribe victory. The 14 innings of scoreless ball are impressive but were far from a thing of beauty. Turbeville issued 13 passes (one intentional), including walking the bases full in the 13th inning. He surrendered nine hits and tossed three wild pitches.

With that many baserunners how did Turbeville prevent scoring? The infield recorded six double plays, setting a new American League record and tying the major-league record at the time.10 Four teams have since turned seven DP’s in a game. Besides the twin killings, the Indians helped Turbeville by trying to run on him and batterymate Paul Richards. Milt Galatzer was caught twice, including in the first inning when he was nabbed trying to steal home on a double steal. The Indians made four steal attempts; all were thwarted.11

Three days later Turbeville pitched another complete game, this time a 5-0 loss in Detroit. That made 23 consecutive innings without support from his offense. He made seven appearances in September covering over 36 innings. Hitters treated him rudely, piling up 34 runs and raising his ERA to 7.63. He desperately needed to find his control. His walks per nine innings (9.8) were the worst on the team.

Newsmen had fun with George being from Turbeville. Some falsely claimed the town was named for him. Others looked to find other players from a town named for their relatives. It was suggested that pitcher Flint Rhem, from Rhems, South Carolina, qualified.12 Others included George “Buck” Stanton, who hailed from Stantonsburg, North Carolina, and Beau Bell from Bellville, Texas.13

The Athletics returned to Fort Myers, Florida, for spring training in 1936. Turbeville was one of 22 pitchers brought to camp by Mack. He struggled with his control in the early intrasquad and exhibition games. On March 18 he turned in a strong four-inning stint against the Cardinals but still walked three. He made the squad as a starter/reliever.

Turbeville took the hill against the Yankees on April 20 with two out in the fourth. The A’s were down 9-4. He coaxed Lazzeri to fly out, then held New York scoreless in the fifth and sixth. In the seventh Turbeville surrendered three hits and a walk to give New York an 11-7 lead. In the bottom half of the frame, the A’s rallied against Bump Hadley and tied the game at 11-11. Turbeville held the Yanks scoreless in the last two innings. In the bottom of the ninth, Hadley’s wildness loaded the bases. Lovell “Chubby” Dean pinch-hit for Turbeville and hammered a hard grounder into left for a 12-11 win. Turbeville celebrated his first major-league victory.

On May 1 Turbeville started against the Tigers. He tossed a complete game but walked seven. He also failed to catch the ball covering first base in the fourth and allowed a run to score. He took the loss, 4-2. Two starts resulted in losses, then Turbeville made a couple of relief appearances. On May 25 he started a home game against the Yankees. He held them scoreless in the first thanks to a double-play grounder from DiMaggio. His teammates staked him to a 2-0 lead in the bottom of the first.

In the second Turbeville got Lou Gehrig to ground out, then lost control and walked the next three batters to bring Lazzeri to the plate. Lazzeri sent a long fly deep into the right-field seats for his first grand slam of the day. When Turbeville followed by walking the opposing pitcher, Mack had seen enough and went to the bullpen. The Yankees bats really came to life in the fourth and beyond. The final score was 25-2.

Mack determined that it was time to send Turbeville to the minors for schooling. He hesitated a day or two and let him get in two more relief appearances before sending him to the Williamsport Grays of the Class A New York-Pennsylvania League after his May 28 appearance.

The local press reported that Mack “liked his stuff and likes his disposition, but he must be cured of his wildness.”14 The consensus was that Turbeville had all the character and brains to be a top- of-the rotation pitcher. All he had to do was learn to control his pitches. His first minor-league experience was bound to be beneficial for him.

Turbeville saw his first action with the Grays on June 1 when he beat Elmira 6-5. Williamsport was in the second division when he arrived. They finished in fourth place. On June 14 Turbeville tossed a seven-inning no-hitter to beat York, 1-0. Later in the season he went on a four-game winning streak. He closed out the season with a 9-5 mark. His walks ratio improved slightly, but he was still far from under control.

Mack recalled Turbeville when the NYP season ended and gave him two late-season starts. He lost to the Yankees in New York, but on September 27 he hurled a complete game in Fenway Park. He beat the Red Sox 8-4 for his second major-league win. He issued only four walks that day.

It is a mystery why Mack handled Turbeville the way he did. If indeed Mack thought Turbeville needed to learn control, why not send him down to the minors? Yet in 1937 Mack kept Turbeville in the majors the entire summer. He pitched in 31 games, only one of which the seventh-place A’s won. He made three starts and lost two of them. He closed out the year at 0-4 with a 4.75 ERA. Turbeville made his final major-league appearance against the Yankees in New York and issued five walks in two innings of relief. He closed his out his career 2-12 in 62 games with an ERA of 6.14.

In December Connie Mack optioned Turbeville to Oakland of the Pacific Coast League as part of a deal for Dario Lodigiani. Turbeville opened the 1938 season with the Oaks. On May 14 the A’s included him in a deal with the Columbus Red Birds of the American Association for Dick Siebert. Now a part of the St. Louis Cardinals farm system, he pitched in 15 games for Columbus before being sent to Asheville of the Class B Piedmont League on July 16.

With the Tourists Turbeville lost his first start, 4-2 to the Norfolk Tars. A week later he beat the Tars 3-0. He closed out the season by driving in the winning run in the bottom of the ninth in a 3-2 win over Rocky Mount. His sizzling fastball helped him post a 7-5 record.

Turbeville earned the right to pitch Opening Day for the Tourists in 1939. Before 1,365 fans at McCormick Field, he overpowered the Charlotte Hornets for a 6-3 win. He got off to a strong start and the Tourists enjoyed the scenery in first place early in the year. On May 20 Turbeville faced Norfolk on the road and went 5-for-5 at the plate. The Tars returned the favor and lashed 16 hits off him in eight innings. The Tourists lost in the ninth, 9-8.

Turbeville started to unravel after that. He lasted only four innings in his next outing and started to have control problems. In late July he was fined $50 and suspended for breaking training rules. He returned home to Turbeville. In September Turbeville joined Sumter in the semipro Palmetto League and pitched the remainder of the season. Asheville sold his rights to Sacramento of the PCL in September.

The Palmetto League was the premier semipro league in eastern South Carolina for two decades. Teams would usually play three days a week. Turbeville joined Sumter again in 1940 and stayed until Sacramento exercised its rights and activated him in late June. The Solons (part of the Cardinals system) had a farm club in Portsmouth, Ohio, that was struggling and mired in last place. Portsmouth replaced manager Fred Dorman with farmhand Walter Alston and added four pitchers, including Turbeville.15

Portsmouth was in the Class C Middle Atlantic League. Turbeville lost his first outing to Canton, 2-1. He had 12 strikeouts and walked four. During a five-day span in July, he won three games. On July 20 he tied the league strikeout mark for the season when he set down 14 Canton batters. He closed out the season with a 7-7 record, but the Red Birds could not escape the cellar. In December Turbeville’s rights were returned to Sacramento.

The Sacramento Solons in 1941 were managed by Pepper Martin. Turbeville traveled cross-country for training camp. He rounded into shape nicely, showed control on his pitches and was considered a possible Opening Day pitcher. Veteran Tony Freitas got the nod, but Turbeville started the second game of the season. He went eight innings and had a no-decision in the Solons’ win.

Martin used a six-man pitching rotation and the team got off to a fast start. The Solons were 22-7 on May 8 and 43-19 a month later. Turbeville took his turn but as May closed out, he struggled and was pulled in four consecutive games because of wildness. He won his start on June 12, beating Hollywood 8-1 despite issuing 10 walks. Martin sent Turbeville to the bullpen and he only had the occasional start the rest of the season. Sacramento cooled off and returned to the pack. After leading the league for all but 13 days, the Solons had to settle for second place.

The Pacific Coast League used a playoff system and the Solons faced the San Diego Padres in the first round. Sacramento swept the Padres in four games and faced the Seattle Rainiers in the finals. Seattle took the crown four games to three. Martin used just four pitchers in the two series as Turbeville watched from the bench.

Turbeville was blessed with a strong body and good looks. The sports editor of the Portland Oregonian declared him the “handsomest pitcher in the Pacific Coast league.”16 His good looks must have given him a more youthful appearance than his actual age. He was listed as 23 years old despite turning 27 during the season.

Turbeville returned to the Coast for spring training the following season. He was given the start against the Philadelphia A’s on March 11. His former team treated him harshly, scoring six runs in the first inning. Sacramento sold Turbeville to the New Orleans Pelicans of the Class A1 Southern Association in mid-April.

Turbeville opened the season in fine form for the Pelicans. He beat Knoxville and surrendered only two walks. He followed that with a win over Little Rock in which he issued only two passes. On May 27 he walked three in the first inning but went on to beat Chattanooga on a three-hitter in which he struck out 14. He closed the month with a win over the Birmingham Barons when he fanned nine.

Opposing teams started using their ace when Turbeville pitched and he dropped some close contests in June. Nevertheless, he was named to the Southern Association All-Star squad that faced league-leader Little Rock on July 9. He had a 5-6 record at that time.17 He did not see action but was rewarded with travel expenses and $25 in War Stamps.

Turbeville’s pitching faltered in the second half. One of his worst outings was against Atlanta when he allowed 15 runs, but he did smack an eighth-inning double to ruin his opponent’s no-hit bid. The Pelicans finished fourth and dropped the first round of playoffs to Little Rock. George closed out the year at 8-11 with the best ERA of his career (3.79). His early-season success with control vanished and he closed out the year with 123 walks in 171 innings.

The Army Air Corps called Turbeville to duty and he reported to Shaw Air Base in Sumter, South Carolina. He spent the entire war stateside. After time at Shaw Turbeville was transferred to Maxwell Air Base near Montgomery, Alabama. He pitched for the base teams wherever he was stationed. It was reported that he amassed a record of 60-8 with four no-hitters during his career in the military.18

Turbeville went to spring training in 1946 with the Pelicans. He had some brilliant moments and won the Opening Day assignment in New Orleans on April 12 versus the Mobile Bears. The game was tied 4-4 in the 11th when Turbeville threw a wild pitch to give the Bears the lead. The Pelicans rallied in the bottom of the inning for a 6-5 win. Turbeville’s arm stiffened and he was sidelined. He had minor surgery which shelved him until June 15. He made six more starts and posted a 2-2 record before calling it quits in late July. Turbeville returned to the Palmetto League with Lake City in 1947 as a pitcher-outfielder. The following year he seldom pitched but provided a big bat for Sumter.

Little can be found on Turbeville’s life after baseball. His first marriage was childless and ended in divorce in 1945. He had a second marriage to the former Sara Gaskins that endured until his death. There were no children in the second marriage either. He battled health issues of an undisclosed nature and would spend time in the Veterans Administration Hospital in Salisbury, North Carolina. In 1974 his sister listed that as his permanent address.19

Sara G. Turbeville lived in Columbia, South Carolina, at the time of George’s death on October 5, 1983. He was buried in Greenlawn Memorial Park in Columbia.

During his career the words “sizzling” and “overpowering” were used to describe Turbeville’s fastball. Many fastball hurlers with great speed are compared in the press to other speed artists. Turbeville’s fastball, for reasons unknown, did not draw comparisons to any contemporaries or predecessors.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Len Levin and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

The Sacramento Bee and the Asheville Citizen-Times were used to comment on Turbeville’s 1938-39 and 1941 seasons.

Notes

1 en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turbeville,_South_Carolina, last accessed on November 7, 2018.

2 “George Turbeville, Retired Baseball Player,” The State (Columbia, South Caolina), October 7, 1983: 5.

3 Turbeville’s enlistment papers for World War II, shown on ancestry.com, give his height as only 71 inches.

4 “Elloree Captures Title,” Charleston (South Carolina) News and Courier, April 30, 1933: 8.

5 “Johnson Finds Two Ineligible,” The State (Columbia, South Carolina), July 2, 1933: 9.

6 Noted on Turbeville’s Hall of Fame questionnaire. Oddly, it does not mention that he also attended North Carolina University.

7 James C. Isaminger, “Turbeville Able to Let Fly with Both Wings,” The Sporting News, September 12, 1935: 2.

8 Isaminger.

9 Sam Otis, “Elusive 13th Has Harder on Ropes,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 21, 1935: 28.

10 “0-0 for Fifteen Innings Then Earl Hits It,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 25, 1935: 12.

11 Sam Otis, “Averill’s Homer in 15th Beats Athletics, 2-0,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 25, 1935: 27.

12 Isaminger.

13 Sam Otis, “Turbeville Hails from Turbeville,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 27, 1935: 29.

14 James C. Isaminger, “Turbeville Slated to go But Connie Mack May Keep Erratic Moundsman,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 28, 1936: 21.

15 “New Manager for Red Birds,” Dayton (Ohio) Journal Herald, June 25, 1940: 9.

16 L.H. Gregory, “Greg’s Gossip,” Portland Oregonian, October 2, 1941: 25.

17 “Southern Stars Face Little Rock Nine,” Tampa Times, July 9, 1942: 12.

18 “Pelican Hurler Out of Service,” Tampa Tribune, February 2, 1946: 21.

19 Shown on his Hall of Fame questionnaire.

Full Name

George Elkins Turbeville

Born

August 24, 1914 at Turbeville, SC (USA)

Died

October 5, 1983 at Salisbury, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.