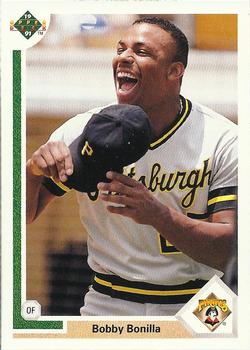

Bobby Bonilla

“He’s a quality player who’s getting better all the time. A year ago, he played on talent alone. Now he’s doing it on talent and know-how. His potential is unlimited.”1 — Pittsburgh Pirates manager Jim Leyland

No word better describes Bobby Bonilla’s baseball career than “potential.” He was selected as an All-Star six times. Bonilla won three Silver Slugger Awards while a Pirate. Toward the end of his career, he helped lead the Florida Marlins to an improbable World Series triumph. In spite of all this success, Bonilla seemed trapped inside a bubble of bigger expectations.

No word better describes Bobby Bonilla’s baseball career than “potential.” He was selected as an All-Star six times. Bonilla won three Silver Slugger Awards while a Pirate. Toward the end of his career, he helped lead the Florida Marlins to an improbable World Series triumph. In spite of all this success, Bonilla seemed trapped inside a bubble of bigger expectations.

Standing 6-feet-3 and weighing 210 to 240 pounds, Roberto Martin Antonio “Bobby” Bonilla was always a big man from the time he began playing professional baseball. He was similar in build to two former Auburn University football players, Frank Thomas and Bo Jackson, who like Bonilla tantalized Chicago White Sox fans with their potential to put a big hurt on every baseball. Bonilla was not a finesse hitter, or even a traditional home-run hitter. “He simply muscled the ball with the brute strength of an offensive tackle, which he resembled in appearance,” one writer explained.2

There is great irony in the pressure for Bonilla to achieve even more than he did. When Bobby was born on February 23, 1963, the area dominated by the Jackson Houses of the South Bronx was not a neighborhood full of high expectations. Puerto Rican families, mostly low income, were pouring into the Bronx in huge numbers. The Bronx has been the political bulwark of nationally ground-breaking Puerto Rican politicians including Herman Badillo, Fernando Ferrer, and Jose Serrano. The Bronx is the second largest population area of Puerto Ricans, behind only San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Bonilla is of Afro-Puerto Rican heritage, his parents having moved to the Bronx from Puerto Rico. Roberto Sr. was an electrician and Regina, his mother, was a psychologist. They divorced when Bobby was 8. He, his twin sisters, Socorro and Milagros, and his brother, Javier, grew up living with their mother. His father lived only five minutes away. Bonilla said that “he was always there if I needed him.”3 Both parents worked to instill values in him though actions and words. His father took Bobby on electrical jobs to demonstrate how hard he had to work as well as the dangers of his job, and then, according to Bonilla, would ask, “Is this what you want to do?” and Bobby would reply “No, Dad, I’ll work at my baseball a little harder.”4

His home area was the infamous 40th Police Precinct, known for its homicides and robberies and not many success stories. Bonilla said that he “had my sports.” “It kept me away from the drugs, the gangs,” he told Ross Newhan of the Los Angeles Times.5 Amidst the chaos, Bobby focused on baseball. He told People magazine that he “played sports 24 hours a day. In a place like the South Bronx, you have to dream or else you’ll get caught up in the mess.”6 His life in the Bronx led to one of his oft-repeated phrases when people asked him if criticism, booing fans or batting slumps were “pressure.” He’d say: “This isn’t pressure. Pressure is growing up in the South Bronx.”7

Not only did Bobby have his family to keep him focused, but he had an extraordinary high-school baseball coach, Joe Levine. Beyond just helping develop Bonilla as a high-school player, Levine put him in the position to launch an improbable and extraordinary major-league career. The coach attended a seminar at which a high-school all-star team was being assembled to play in Scandinavia in the summer of 1980. High-school senior Bonilla was selected for the team, but did not have the money needed to go. His coach started a “Bobby Fund” to assist Roberto Sr. in paying for the summer trip. It is no wonder that Bonilla considered Coach Levine a second father.8

The coordinator and instructor for the trip was legendary baseball scout Syd Thrift. Thrift had spent nearly 20 years as the scouting coordinator of Pittsburgh Pirates, Kansas City Royals, and Oakland Athletics but had left baseball and was working during this nine-year stretch as a real estate agent. Here’s how Thrift described the trip: “It was the season of the midnight sun. We all slept in one big room. There were no shades on the windows and the sun never set. It was the most bizarre thing you ever saw.” 9 But it gave Thrift plenty of daylight to see Bobby Bonilla’s potential.

Upon returning, Thrift called one of his old bosses, Pirates minor-league director Branch Rickey Jr., and within weeks of returning, Bonilla was at the Pirates’ spring home in Bradenton, Florida for a tryout.10 Bonilla was not an instant success story in minor-league baseball. He spent his first two years with the Pirates’ rookie league team, hitting barely above the Mendoza line though occasionally flashing his potential power. At age 20, in 1983 at the Class-A level, Bonilla began to show improved skills so the Pirates advanced him to Nashua of the Double-A Eastern League in 1984. There he again slightly improved his power, average, and speed even though he had risen to a higher level in the minors.

In 1985 Bonilla was invited to spring training with the Pirates in Bradenton. He was getting his breakout chance, but Bonilla broke his leg in a collision with Bip Roberts while chasing a foul popup. He could have given up but did not. Bonilla credited his wife, Millie, his high-school sweetheart, with “keeping his head straight.” “I was a big baby in a lot of ways,” Bonilla said. “I had to learn to cope while wanting to be home. I earned $650 a month and spent $200 calling Millie. She picked up a lot of the slack. She kept my head straight.”11 The Pirates sent him back down to Class A with Prince William (Carolina League). There he met Barry Bonds, who was to become his closest friend in baseball.

In the winter of 1983-84, Bonilla had played his first baseball in his parents’ native home of Puerto Rico. He was still a raw minor-league player when he joined the Senadores de San Juan. Mako Oliveras had taken over as manager and immediately liked the personable Bonilla. Since Bonilla had nowhere to stay, Oliveras asked his mother if Bobby could stay with them. He did so for two winters, where he loved the food and became part of their family.12

Bonilla played four additional seasons in the Puerto Rican Winter League. Before the 1984-85 season, the Indios de Mayaguez traded shortstop Adalberto Pena and pitcher Orlando Lind to San Juan for Bonilla. Assistant general manager Jorge Aranzamendi, based upon all the major-league scouting reports he had access to, supported going after prospect Bonilla because of his potential. While Pena helped lead San Juan to a championship, Bonilla was not a regular starter on Mayaguez until 1985-86.13 Bonilla credited the Puerto Rican Winter League with advancing his skills. He had short high-school baseball seasons in New York City, so he entered minor-league ball without much game experience. After his spring-training injury in 1985, and his demotion back to Class A, the winter of 1985-86 was of great importance to his major-league career. His solid statistics during the last 39 games of the season at Prince William reflected improving skills that resulted in his starting for Mayaguez.

Based upon his broken leg and partial season in Class A, the Pirates had left Bonilla off their 40-man roster in the fall. They presumed that no team would select him in the Rule 5 draft because it would require placing an inexperienced, possibly damaged player on the 25-player roster for the season or potentially losing him. The Chicago White Sox had the advantage of being able to select the unprotected Bonilla after he had demonstrated recovery not only in a few months of minor-league baseball but also with the Indios in winter ball. For $50,000 the White Sox received a soon-to-be major-league star.

Bonilla astoundingly jumped from Class A to the majors without missing a beat. In 75 games for the White Sox,his .256 batting average slightly exceeded his best year in the minors and his on-base percentage and slugging average were roughly equal to his previous bests. No wonder Bonilla said that playing Puerto Rican Winter League baseball was particularly important to him because he skipped Triple A. Puerto Rico had been a critical training ground to maturing and developing his skills.

Bonilla had a friend who had never forgotten him: Syd Thrift. Thrift had been enticed back into baseball by the Pirates, who appointed him general manager. Thrift hired the White Sox third-base coach, Jim Leyland, to be the manager. In midseason the Pirates reacquired Bonilla for pitcher Jose DeLeon. In 2013 ESPN ranked each major-league team’s best deadline trade. For the Pirates, it was receiving Bonilla for DeLeon.14

Bonilla returned to Indios de Mayaguez for the 1986-87 winter season. Post-season he was selected play for the Puerto Rican entry in the 1987 Caribbean Series held in Hermosillo, Mexico along with other major-league players Candy Maldonado and Juan Nieves, as were future stars Roberto Alomar and David Cone. Because of his Puerto Rican heritage, in the winter leagues and for the national team, Bobby Bonilla was classified as a Puerto Rican native player.15 In retirement Bonilla has continued to support baseball efforts in Puerto Rico, including the Puerto Rico Baseball Academy that produced Houston Astros star Carlos Correa.16

In 1987 for the Pirates, Bonilla showed the first signs of a major breakout. He hit .300 (his previous high had been .269), topped 10 home runs for the first time, and slugged .481. He played his last year of winter ball for Mayaguez in 1987-88. In 1988 Bonilla hit 24 home runs and had 100 RBIs. The Pirates excelled as well, as Thrift built a powerhouse upon the ruins of the cocaine-devastated Pirates. From 1988 to 1991, Bonilla averaged 24 home runs, 38 doubles, 102 RBIs, and a 4.4 WAR. While Bonds was the top star with a Wins Above Replacement (WAR) average of 7.9, Bonilla was among the best players in the majors. In 1988, at the start of Bonilla’s outburst, Philadelphia Phillies third baseman Mike Schmidt said, “He’s the best all-around third baseman in the league.”17

The Pirates had become the dominant team in the majors, winning three straight division titles in 1990, 1991, and 1992. Bonilla finished second in the National League’s 1990 MVP voting (behind teammate Bonds) and third in 1991 (Bonds was second to Terry Pendleton of the NL Champion Atlanta Braves). The Spring 1991 issue of Topps Baseball Card magazine featured Bonilla and Bonds on the cover, calling them the “Killer B’s.”18 Topps correctly realized that the double B’s of Barry Bonds and Bobby Bonilla, combined with their first-second and second-third place MVP finishes, and the Pirates’ natural bee-colored black and gold uniforms, made the duo the perfect “Killer B’s” of all time.

Bonilla was not with the Pirates during the 1992 championship season. His life had started to take a bad turn during the 1991 season as his coming free agency began to raise dissatisfaction about money. Bonilla had always been known for having a “neon” smile. People magazine stated: “Perhaps not since Ernie (‘It’s a great day for a ballgame’) Banks retired from the Chicago Cubs 17 years ago has baseball seen a man with a sunnier disposition swing a meaner bat.” A teammate said it was nice to come to the ballpark and see his smiling face.19

Money had become a proxy for not only skill but respect. The Pirates had been a home to African American stars, and had fielded the first all-black lineup in 1971, anchored by Puerto Rican legend Roberto Clemente and Willie Stargell. However, Bonilla felt that teammate Andy Van Slyke and others were given large contract offers while the Pirates would not meet his request. The Yankees were interested in either Bonds or Bonilla but were rumored to prefer Bonilla because of his upbeat attitude.20

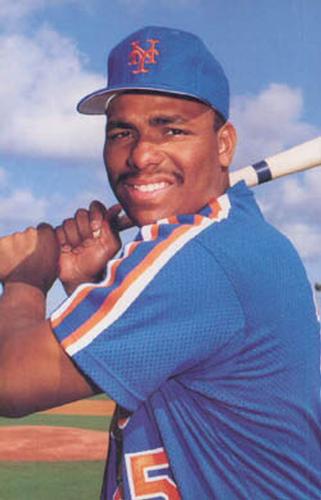

However, it was not the Yankees, but the New York Mets that brought Bobby Bonilla home to New York City. The Mets signed Bonilla to the highest dollar contract ever in the major leagues at the time, $5 million for five years. New York is considered a tough sports town, with many opinionated sports journalists competing for the attention of millions of opinionated and passionate sports fans. Bonilla, as the newly minted richest man in baseball, was going to have a bullseye on his head even if he performed well.

However, it was not the Yankees, but the New York Mets that brought Bobby Bonilla home to New York City. The Mets signed Bonilla to the highest dollar contract ever in the major leagues at the time, $5 million for five years. New York is considered a tough sports town, with many opinionated sports journalists competing for the attention of millions of opinionated and passionate sports fans. Bonilla, as the newly minted richest man in baseball, was going to have a bullseye on his head even if he performed well.

Barry Bonds accurately framed the difference between himself and his good friend. “I can handle New York because I don’t get my feelings hurt the way Bobby does. I don’t give a __ what people write about me or say. Bobby does. He’s too sensitive. I told him before he went there that he wasn’t going to be able to deal with it but he didn’t believe me. Now, he believes me.”21

Bonilla’s return home started like the dream he hoped it would be. On February 3, 1992, he and his wife established the Millie and Bobby Bonilla Public School Fund. Bronx Borough President Fernando Ferrer proclaimed the day Bobby Bonilla Day, stating what a great pleasure it was “to welcome back the four-star slugger of the South Bronx.” Surrounded by Mets officials and teacher union representatives, Bonilla pledged to donate $500 for each RBI he got for sports equipment and incentive programs to the Bronx schools he attended. It was expected to be around $50,000 because Bonilla had become a reliable 100 RBIs-a-year player. Lehman High School was not represented at the ceremony because the principal had fired Bonilla’s beloved former coach Levine. Instead, Levine spoke at the ceremony and the New York Times noted that he would be the “unofficial administrator of the fund.”22

From there, things went downhill. Bonilla sank back to the mediocre performance level of his first year — he was hitting only .130 in May — only now he was the highest paid player in baseball. He improved but still drove in only 70 runs, largely because the weak Mets lineup had 31 percent fewer runners for him to potentially drive in.23 Regardless of the reasons, fans were focused upon his underperformance compared with his record-breaking salary. He was scalded in New York, where he took to wearing earplugs, and his baseball homecoming to Pittsburgh was a disaster, including having a bottle thrown at him. The Mets imploded. Then it got worse.

The days of fawning sports reporters was over. The adoring public was no longer so adoring but more sarcastic. The title of the book The Worst Team Money Could Buy suggests the views of the author about the 1992 Mets.24 The generally ebullient Bonilla was already upset with the world and upset with himself. He said later that he perhaps should have handled the criticism better, but when he was called out for lying about his attempt to reverse an error call on what he thought was a hit, the festering wounds to his pride were picked open. The powerful Bonilla physically intimidated the less imposing author/New York Daily News baseball reporter Klapisch by threatening to “show him the Bronx.”25 It was ironic since Bonilla had specifically separated himself from the more violent part of the Bronx his entire life, but the image of sunny Bobby never quite recovered.

After his poor performance in 1992, Bonilla recovered to have a solid season for the Mets in 1993, as well as in the strike-shortened seasons of 1994 and the first half of 1995. He was named to the NL All-Star team in 1993 and 1995. His statistics averaged over a full season were just shy of his annual performances in Pittsburgh. But now his personal image had been damaged, and his contract had raised expectations to levels he could not achieve.

In late July of 1995 the Mets traded their All-Star slugger to the Baltimore Orioles for two minor-leaguers. Bonilla, clearly glad to escape, drove to Baltimore that night in order to be in the lineup against the White Sox.26 He hit extremely well for the Orioles in 1995, batting .333 with a slugging average of .544 and an RBI rate of 123 in a 162-game season. He followed that with another solid season in 1996. Bonilla was one of the reasons the Orioles made the 1996 American League playoffs as the wild-card team. He hit a game-sealing grand slam in the first game against the Cleveland Indians, and then homered again in the decisive fourth game. Baltimore defeated the Indians three games to one but was easily subdued by the Yankees in the ALCS.

When his season concluded, Bonilla was again a free agent. He signed with the Florida Marlins, where he was reunited with his former Pirates manager Jim Leyland. In 1997 he batted .297 with 39 doubles, 96 RBIs, and 17 homers. The Marlins’ owner, Wayne Huizenga, had decided to open his checkbook, not only for Bonilla but also for Moises Alou, Alex Fernandez, and Jim Eisenreich. The Marlins made the NL playoffs as the wild-card team. It was Bonilla’s fourth trip to the playoffs. This time the Marlins won the World Series, against Cleveland.

After the World Series victory, Huizenga, a trash magnate, trashed his team. He sold, failed to re-sign, or traded most of the key players. The Marlins went from first to worst, finishing 1998 with a 54-108 record. In May 1998 Bonilla was traded, along with Gary Sheffield and three others, to the Los Angeles Dodgers for Mike Piazza and Todd Zeile, who were then flipped as well. Bonilla’s glory days were gone. His hitting collapsed (.249 for the season) and he was bounced to the Mets for Mel Rojas after the season.

At this late stage of his career, Bonilla was not a hitting asset but was more like a good-luck charm. For the 2000 season, he signed with the Atlanta Braves. They won their ninth straight division title. He was not re-signed. For 2001, at age 38, he played in 93 games for the St. Louis Cardinals, who won the NL wild-card slot. They were eliminated by the eventual World Series champion Arizona Diamondbacks. Bonilla’s stellar playing career ended much as it had begun. It was an arc, beginning in 1981 with the Pirates Rookie League team, for which he hit .217, and finishing with a .213 batting with the Cardinals 20 years later.

However, it did not end the baseball legend of Bobby Bonilla. In 1999, his last year with the Mets, Bonilla had agreed to have his contract bought out and accepted deferred payments that would begin in 2011 and continue until 2035. On July 1 of each year he receives a check for $1,193,248.20 from the Mets on what the media refers to as “Bobby Bonilla Day.” Some refer to him as the “Patron Saint of Bad Contracts,” and others refer to players who also are receiving deferred paychecks long after retirement as the “Bobby Bonilla All-Stars.”

Since Bonilla has not played for the Mets since the last century, the fact that his annuity exceeds the salary, for example, of any of the 2016 Mets’ top four pitching stars — Noah Syndergaard, Jacob DeGrom, Matt Harvey, and Steven Matz — causes lots of tsk-tsking by the media and fans. Of course, when Bonilla was slugging away as a youngster for the Pirates he was not earning the big money either. More importantly, even though the Mets will have paid Bonilla $29.8 million for the 2000 season in which he was not on the team, the deal was both logical at the time and worked out well for the Mets. The biggest problem was scam artist Bernie Madoff. Mets owner Fred Wilpon was one of the investors Madoff defrauded of $17 billion for which he was sentenced to 150 years in prison. Wilpon had been receiving 10-15 percent annual gains. Had he earned even 10 percent on the $5.9 million owed Bonilla in 2000, by 2035 Wilpon would have netted a $49 million profit. In attempts to recover losses, Wilpon was sued but found innocent of any crime. He was guilty only of a combination of misplaced trust and economic ignorance.27

The cash freed up by the Bonilla deferred deal resulted in the signing of Derek Bell, Todd Zeile, and Mike Hampton. They helped lead the Mets to the National League title in 2000. Hampton earned the MVP of the NL Championship Series by pitching 16 shutout innings. When Hampton then signed with the Colorado Rockies, the Mets received as compensation a young ballplayer named David Wright, who developed into one of the 10 best Mets players ever.28

Bonilla had one other unique side of his personality: He had some minor success as an actor. Bonilla, Bonds, and Pedro Guerrero all had bit parts in the 1993 baseball movie Rookie of the Year. The movie is the story of a 12-year-old boy who, after hurting his arm, finds that the surgically repaired arm enables him to throw a baseball over 100 miles per hour. This results in his being signed by the Chicago Cubs and sparking them to a World Series victory. He reinjures his arm and returns to Little League baseball, only sporting a World Series ring.

The brief appearance of Bonilla is in one of the scenes that adds the patina of authenticity to the movie. The first is the day at Wrigley Field, filmed at the ballpark, when young Henry Rowengartner (Thomas Ian Nicholas) returns an opposing team’s home run toward the field, only it goes to the catcher at home plate on the fly. Later, after his shaky early start, the “rookie” pitcher becomes a key part of the Cubs turnaround. Showing actual baseball players Bonilla, Guerrero, and Bonds swinging mightily, and late, on the alleged fastballs of the 12-year-old pitcher was a shortcut way to establish Henry’s importance to the Cubs success. The ballplayers in the scene were billed as “The Big Whiffers.”

The movie had mini-cult status among Cub fans desperate to win. Nicholas was invited to toss out the first pitch at a Cubs game in 2010, and to sing the National Anthem in 2015. After the Cubs won Game Seven of the 2016 World Series, he tweeted out the final shot from Rookie of the Year, when he held his World Series ring up to the camera.

The personable Bonilla was also interviewed on nontraditional baseball shows including the Late Night With David Letterman and Lauren Hutton and… He also appeared in three television series. In 1994 Bobby was “Ronnie Holland” in the episode “The Friendly Neighborhood Dealer” on the Fox series New York Undercover. The series ran from 1994 to 1998, starring Michael DeLorenzo and Malik Yoba as NYPD detectives. DeLorenzo, like Bonilla, was of Puerto Rican descent and from the Bronx.

In 1995 Bonilla appeared on Living Single in an episode titled “Play Ball.” The series was carried five years by Fox, ranking among the top five shows among African-Americans. Among its stars were Queen Latifah, Kim Fields, and Kim Coles. In 1998 Bonilla and Tony LaRussa appeared in the episode “The American Game” on the HBO television series Arli$$. While it was critically panned, Time magazine reported that so many viewers claimed Arli$$ was the sole reason they subscribed to HBO that it remained on the year for seven seasons.

By any standard, young Roberto Martin Antonio “Bobby” Bonilla of the South Bronx achieved his potential.

Last revised: June 1, 2017

This biography originally appeared in “Puerto Rico and Baseball: 60 Biographies” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Edwin Fernández. It also appeared in “From Spring Training to Screen Test: Baseball Players Turned Actors“ (SABR, 2018), edited by Rob Edelman and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author utilized Baseball-Reference.com for all baseball statistics and the website IMDb.com for information on Bonilla’s movie and TV career.

Notes

1 Ross Newhan, “An Act of Piracy: Getting Bonilla Back Was a Steal,” Los Angeles Times, July 8, 1988.

2 Bob Klapisch and John Harper, The Worst Team Money Could Buy (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, Bison Books, 2005), 75.

3 Newhan.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Eric Levin and Mary Huzinec, “Save That Ball, Boys — The Way Bobby Bonilla’s Going, It’ll Be Valuable,” People magazine, July 18, 1988.

7 Ken Rappoport, Bobby Bonilla (New York: Walker and Company, 1993), 91

8 Kenneth Shouler, “Swinging for the Fences,” Cigar Aficionado, July/August 1998; Newman, “Act of Piracy.”

10 Shouler.

11 Newhan.

12 Thomas E. Van Hyning, Puerto Rico’s Winter League: A History of Major League Baseball’s Launching Pad (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1995), 29.

13 Ibid.

14 proxy.espn.com/blog/sweetspot/tag?name=bobby-bonilla.

16 “MLB to Start Puerto Rico Summer League for 14-17-Year-Olds,” Fox Sports, June 19, 2014.

17 Levin and Huzinec.

18 While some have included Sid Bream and Jay Bell among the Pirates’ “Killer B’s” and others later stretched the term to the powerful Houston “B’s” (Jeff Bagwell, Craig Biggio, and Derek Bell), the term fit perfectly on Bonilla and Bonds.

19 Ibid.

20 Jon Heyman, “Yankees Are Targeting Bonds or Bonilla,” Newsday (Long Island, New York), January 13, 1991.

21 John Feinstein, Play Ball: The Life and Troubled Times of Major League Baseball (New York: Villard Books, 1993), 26.

22 Bruce Weber, “Bobby Bonilla Puts His Bat to Work,” New York Times, February 4, 1992.

23 Neil Paine, “Bobby Bonilla Was More Than the Patron Saint of Bad Contracts,” FiveThirtyEight.com, September 30, 2016.

24 Klapisch and Harper.

25 Rappoport, 286.

26 Buster Olney, “All-Star Slugger Acquired From Mets for Minor-Leaguers Ochoa and Buford Orioles Get Their Cleanup Man: Bonilla,” Baltimore Sun, July 29, 1995.

27 theundefeated.com/features/bobby-bonilla-was-more-than-just-that-mets-contracts-538/; Serge Kovaleski and David Waldstein, “Madoff Had Wide Role in Mets’ Finances,” New York Times, February 1, 2011; and Darren Royal, “Why the Mets Pay Bobby Bonilla $1.19 Million Every July 1,” ESPN; July 1, 2016.

28 Mel Antonen, “Deferred Payment: Mets Owe Bobby Bonilla Nearly $30 Million From 2011-2035,” USA Today; updated July 1, 2010; Ted Berg, “The Annual Deferred Payments to Bobby Bonilla Actually Worked Out Quite Well for the Mets,” USA Today; July 1, 2015.

Full Name

Roberto Martin Antonio Bonilla

Born

February 23, 1963 at Bronx, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.