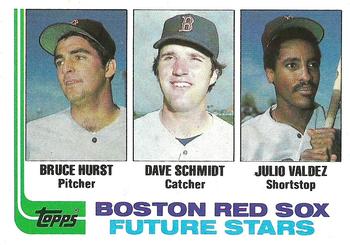

Dave Schmidt

Dave Schmidt was a catcher with the Boston Red Sox in 1981. He played for them in 15 games at the start of the season and acquitted himself well. But the Sox had two other solid catchers — Rich Gedman and Gary Allenson, who filled most of the team’s needs for the next several years. Schmidt (a 6-foot-2, 215-pound righty batter) was odd man out, and then got hurt. He was with the Red Sox organization for eight years from 1975 to 1982, but only enjoyed the one major-league stint.

Dave Schmidt was a catcher with the Boston Red Sox in 1981. He played for them in 15 games at the start of the season and acquitted himself well. But the Sox had two other solid catchers — Rich Gedman and Gary Allenson, who filled most of the team’s needs for the next several years. Schmidt (a 6-foot-2, 215-pound righty batter) was odd man out, and then got hurt. He was with the Red Sox organization for eight years from 1975 to 1982, but only enjoyed the one major-league stint.

David Frederick Schmidt was born on December 22, 1956, in Mesa, Arizona. His parents were Californians. Herman Schmidt had grown up in Laguna Beach and Saundra in Glendale. They were in Arizona because Dave’s father was finishing his master’s degree at Arizona State. “I had a good gene pool,” Dave said in an April 2020 interview. His father had a football scholarship to St. Mary’s but hurt his knee. “Then he got a track scholarship to Arizona State to throw the discus. He went there. My mom Saundra was probably a better athlete than any of us.”1 Herman Schmidt became athletic director at La Cañada High School, and then moved to Mission Viejo when he had the opportunity to become a vice-principal at Tustin High School. “I have an older sister, Elizabeth. She’s a schoolteacher. I have a brother Eric. He actually signed with the Dodgers the year after me. We were 11 1/2 months apart. The old Irish twins. He was a left-handed pitcher. Signed out of Mission Viejo High School the following year.” Eric Schmidt was a 19th round pick of the Dodgers in the 1978 draft; he spent four years pitching in the Dodgers’ minor-league system.2

The Red Sox had selected Dave with their second-round pick in the June 1975 major-league amateur draft. He was signed by scout Joe Stephenson. His first assignment was to the Elmira Pioneers in the short-season Class-A New York-Penn League. Playing for manager Dick Berardino, Schmidt played in 59 of the team’s 68 games, batting .249 with three homers and 20 runs batted in. He was one of two catchers named to the league’s All-Star team.

In 1976 he played for the Winter Haven Red Sox in the Class-A Florida State League. The team finished 65-76 for manager Rac Slider. Schmidt caught in 64 games, and appeared in five others, batting .221 and driving in 28 runs.

After turning 20, Schmidt played both 1977 and 1978 for the Winston-Salem Red Sox (Carolina League). It was again Single-A baseball, but he spent those two years establishing himself. He appeared in 120 games the first year, catching most of the time but also playing 16 games at first base and serving as a designated hitter. He hit for a .236 batting average, hit 14 home runs, and collected 53 RBIs. In 1978 he upped his average to .269 in 105 games, again with 14 homers, this time with 48 RBIs. He doubled the number of games he played first base to 32.3

In 1979 he was promoted to Double A and had a breakout season for the Bristol Red Sox (Eastern League).4 He appeared in 117 games and led the team in all three Triple Crown categories — .332 BA/19 HR/73 RBIs. His batting average led the league, as did his .453 on-base percentage, and 32 doubles.5 He played outfield in eight games, but only one at first base. He was voted to the Eastern League’s All-Star team as a designated hitter.6 There was some thought he might be brought up to Boston for a “look-see” but he was not. It could be that, since he’d been given more work as a DH, he was no longer seen as attractive as he might have been had he still primarily been a catcher: “The fact that he’s been a designated hitter, not a catcher, puts him a year or two away.”7

Before spring training began in 1980, Red Sox manager Don Zimmer was said to believe of Schmidt that “in three years he has progressed to the point that he can throw as well as anybody.” He was seen as the “heir apparent.”8 Despite playing in Connecticut for two [sic] seasons, Schmidt said, “I’ve never seen Fenway Park in Boston except on TV,” adding, “When I do see it, I want to be in the lineup.”9

The Boston Globe’s Larry Whiteside wrote a piece on Schmidt. Both Carlton Fisk and Bob Montgomery were having arm problems, and Gary Allenson had only hit .203. Red Sox minor-league pitching coach Bill Slack said that Schmidt had had obstacles while coming up. Roger LaFrancois had been on the same team in 1978, and hit more than 40 points higher, while in 1979 Schmidt had been on the same team as Rich Gedman. Slack said, “In the minors, where you want kids to develop, it is hard to have two catchers and get them the right amount of playing time.”10 Schmidt said he’d become a better hitter because of Slack’s work with him, teaching him how to hit the ball to right field. “On paper,” though, Whiteside said of Schmidt (and LaFrancois) “both are a year away.”11 He had not yet had Triple-A experience.

Signed to a Boston contract, Schmidt trained with the big-league club in 1980. On March 30, he was hit in the left temple by a pitch. X-rays cleared him to continue. Rather than keep him around with the Boston club, feeling he would benefit from time at the Triple-A level, the Sox promoted him again, this time to the Pawtucket Red Sox in the Triple-A International League. Schmidt only appeared in 50 games. He caught in 37 with Rich Gedman (84 games) and Roger LaFrancois (41 games) both getting a little more work. Once more, he played in one — but only one — game at first base. It wasn’t that he was DH in the other dozen games; he stepped on a bat and suffered a broken ankle on August 4. He was also “subject to periods of dizziness all season” (vertigo) and so had an inner ear operation in January 1981.12

In March 1981, Carlton Fisk signed as a free agent with the Chicago White Sox. Bob Montgomery had played his last season in 1979. Gary Allenson had only had limited action in 1980, but hit very well. Heading into 1981, the Boston Globe’s Ray Fitzgerald saw four catchers contending to play for Boston. He wrote, “Reading from A to S, and also from favorite to long shot, the names are Gary Allenson, Rich Gedman, John Lickert, and Dave Schmidt.”13 The Red Sox had also acquired Fred Kendall and Dave Rader to help bolster a catching corps they apparently felt was perhaps not ideal. Mike O’Berry, Bo Diaz, and Ernie Whitt were other catchers in the mix before they all were traded away. “There was always a very good rapport among all of us, though. There’s some kind of camaraderie among catchers, I guess.”

That spring, he says, “I was supposed to have no shot and then I hit a pretty impressive home run in Clearwater off of Dick Ruthven, over that center-field monster.” He’d barely been mentioned in the newspapers, but the following day, as he tells it, “[Manager Ralph] Houk said we got three guys going for the job — Gedman, Allenson, and Schmidt. All of a sudden, I was back on the radar a little bit.” And then he got chosen to head north.

“Richie and I had lockers next to each other in Winter Haven. Charlie Moss came over and tapped Richie on the shoulder and said, ‘Go see Ralph.’ You know what that is. When the trainer comes to get you in spring training, you’re going down. I sat there. I was just in shock. I thought I had outplayed him, but it never really mattered. He always got the nod. And Houk never said anything to me. He came out and looked at me and says, ‘Are you happy?’ I go, ‘Ye…eah. I go back to the hotel and I call my mom and dad and I say, ‘I think I made the team.’ Nobody ever said to me, ‘You made the team.’”

Allenson played well in spring training. The long-shot Schmidt made the team as the backup catcher and someone who could handle right-handed pinch-hitting opportunities for Houk, who had declared, “Schmidt is a helluva hitting prospect and he holds his own behind the plate. I think with work he could be a helluva catcher, too.”14 Houk was prepared to start the season with just two catchers — Allenson and Schmidt.15

Schmidt finally got his opportunity to see Fenway Park but he wasn’t in the lineup at any point in April. His major-league debut came on April 28 against the Texas Rangers in Arlington, Texas. The Rangers built a 7-0 lead; before they came up to bat in the bottom of the seventh, Houk put Schmidt in to catch and Bill Campbell to pitch. The Rangers scored two more runs. Schmidt came up with two outs and nobody on base in the top of the ninth, facing reliever Bob Babcock. He struck out, lunging at the third strike. “Call me Samurai Hitter,” he shrugged in a self-deprecating comment.16

Allenson got his first day off on May 5 in Kansas City. Schmidt got his first start. Frank Tanana pitched an excellent game for the Red Sox, allowing only two runs in 7 1/3 innings, but the Royals’ Larry Gura pitched a better game, holding the Sox to one run on just four hits. The first hit he surrendered was a single to center field by Schmidt, leading off the third inning.

On the afternoon of May 9, Schmidt got his next start and his first run batted in. It was in Toronto and he singled his first time up. He walked the second time up, and scored his first run after another walk and a two-run double by Dwight Evans. Boston had a 9-3 lead after eight innings. In the top of the ninth, with Carney Lansford on first base, Schmidt doubled to left field and drove him in.

Allenson’s pulled groin muscle gave Schmidt the opportunity to play in 13 games in May. Gedman was called up to supplement Schmidt. On May 14, Schmidt hit a solo home run into the left-field seats in the top of the 11th inning, which proved to be the winning run against the Minnesota Twins. It wasn’t treated as anything of a magical moment. “When he returned to the bench, his comment was, ‘If we had another catcher, they would have pinch hit for me four innings ago.’ At which point, Ralph Houk, who’d been a Schmidt booster, simply said, “That’s right.”17 Schmidt did admit it was a thrill.18

Only in his seventh game did Schmidt get to play at Fenway Park. He was 0-for-3 on May 15.

A second homer, also a solo home run, came in Milwaukee on May 23.

His 15th and final game in the major leagues was on June 3 in Cleveland. He was 1-for-4.

A player’s strike was looming. Schmidt had worried about the strike. A UPI story two weeks beforehand quoted him as saying, “If it’s a long strike, I’d have to go out and get a job somewhere.” He wasn’t looking forward to having to make his way back across the country if the Red Sox were in Boston at the time. “I live in California and it’s an expensive trip if you have to pay for it yourself.” He added, “If it looks like a strike is going to happen, they might send some of the younger players to Pawtucket.”19

After the June 11 game against the Angels, major-league baseball players went on strike, and play did not resume until August — in Boston’s case against the White Sox at Fenway Park on August 10. Had he been with the team in Anaheim, Schmidt wouldn’t have had to worry about transportation. He’d already have been in Southern California. As it happens, Gary Allenson had come off the disabled list and Rich Gedman had started to hit well. On June 5, Schmidt had been optioned to Pawtucket.20 He thus did have a job, but he wasn’t in the major leagues.

Being employed by the PawSox wasn’t without a degree of anguish, though. “In a way I feel guilty about taking the money,” he said. “Here I am down here with my [Boston Red Sox] teammates out on strike and not getting paid…I was with them for two and a half months, voted for the strike, and now that it’s on, I’m still getting paid and still playing while they’re doing nothing. That’s what makes it kind of strange for me. I’m going to benefit from the Players’ Association, I agree with what it’s doing, yet I’m not being hurt by the strike.”21 He added, “I feel being sent down will be very helpful to me in the future…There’s only one league to play in and once you’ve been there….”22

One subject that had not been broached at the time was the unfortunate timing of his release back to Pawtucket. The Red Sox had just begun a West Coast road trip and were in Oakland. A family reunion was planned, one that included his sister’s wedding in Anaheim and Dave proposing to his own intended. His brother and a friend flew up to Oakland to see him, as did the 22-year-old girl to whom Dave was going to propose. But Gary Allenson was coming off the disabled list. “Right after the game, Ralph Houk called me in and they were sending me down to Pawtucket. I had the engagement ring with me, but before I ever saw her I got sent down to Triple A. It was bittersweet. I still gave her the ring and we got engaged, and then we got married later that year.”

He never did get back to the big leagues.

His time in the major leagues saw him play 15 games, with a .238 batting average but his seven bases on balls gave him a .347 on-base percentage. Unfortunately, he struck out a little over 40% of the time — 17 K’s in 42 at-bats. He had two homers and three RBIs, and scored six runs. His career fielding percentage was 1.000, having handled 57 chances without even one error.

In 63 games at Pawtucket, he hit .194 (.332 OBP — thanks to 39 walks on top of his 37 base hits) with nine homers and 25 RBIs. When rosters expanded in September, it was John Lickert who got the call to be the team’s third catcher. Schmidt’s “poor offensive showing” at Pawtucket had caused him to be bypassed in favor of the younger Lickert.23

Asked about all the walks, Schmidt said, “Billy Beane would have loved me, I bet. That was before they had all the sabermetrics. I went back and looked at my OPS number and it was over 1.000 that year [1979] at Double A. But I struck out a lot. In ’79, I struck out almost 90 times and I walked about 90 times. I had 370 at-bats and I struck out 90 times but I led the league in on-base percentage.”24 Throughout most of his career, the strikeouts came from taking close pitches, not on swings and misses.

What had gone wrong? He was understandably disappointed at being sent down, without ever truly having enough time to establish himself. There was something else. “It sounds like I’m making excuses,” he said, “but the other thing is that I got a staph infection on that inner ear I’d had the operation on. I was having the same symptoms. I was having vertigo again. Morgan said, ‘Where do you want to hit in the lineup?’ and I said fourth, so I was catching every day and hitting fourth and I just didn’t perform. I was horrible. I’m not sure how much of that was due to the vertigo, how much of that was just…I let myself get down. I couldn’t muster up the…it seemed like it was always an uphill battle with the Red Sox. If I were going to make it, I would have had to have gone somewhere else, I think.”

Schmidt played in Pawtucket again in 1982. The Red Sox went with non-roster invitee Roger LaFrancois as the third catcher on the big-league staff. Ironically, that meant they rated Schmidt more highly but it nevertheless had to feel disappointing. Garry Brown explained: “The Red Sox want three catchers, but they don’t want to waste bright prospects like Johnny Lickert, Dave Schmidt or Marc Sullivan in a role which would see them play only sparingly. So those blue-chippers go to the minors while six-year minor league journeyman LaFrancois gets a big league job.”25

Dave Schmidt got in a lot more playing time in 1982, appearing in 70 games for the PawSox. Once more he drew a lot of walks (34), which helped give him an on-base percentage of .373 but his batting average was only .229 with 23 RBIs.

Even though the beaning had been a couple of years earlier, the ear operation, and the staph infection that came later, may have affected him for longer than was appreciated at the time. He also had what seemed to be some deeply-buried injuries. “I had a tough time,” after the beaning, he says. “I’ve never talked about it with anybody, but by the time I got there [Boston] my shoulder was torn up. I got examined not too long ago and I still had a torn rotator cuff, a torn labrum, and a torn biceps tendon. By the time I got to the big leagues, I couldn’t really throw that well. By 1982, they’d kind of given up on me. I couldn’t throw the ball anymore. My arm was gone. It’s amazing how many catchers actually go out with arm trouble.”

It was time to get that other job that he’d been thinking about during the strike year.

His compensation when signing had been more or less par for the course. “I was 39th overall when I was drafted and I got $30,000 cash, $8,000 for college, and a $7,500 incentive clause.” He had attended college, a couple of semesters at Saddleback College, one at Orange Coast College, and a couple of semesters at California State University in Fullerton. He had devoted offseason work to baseball, too, going to instructional league his first year and then spending one winter each playing in the Dominican Republic and in Venezuela. He’d gotten married, and it was time to go to work.

“Back in the day, you could get a job — especially in sales — without a college degree. I had to go to work, I needed to make money, so I did that. I never really had a desire to finish up college. My uncle was an insurance broker up in Glendale and so I went to work for him. I wound up getting a job with a big insurance brokerage called Old Northwest Agents. I was the district manager for Orange County and San Bernardino and Riverside counties. We wholesaled health insurance to the brokers. I made good money doing that. I think in 1989 I made $150,000.”

Schmidt was married twice. Neither marriage lasted long. It was not a subject on which he wanted to dwell, but he believes his first marriage was simply one of two people who were too young to have gotten married (they were 24 and 22, respectively, and in less than a year, Schmidt was out of baseball and needed to put on a suit and join the corporate world.) His second marriage, to a former Miss Georgia, was perhaps entered into too hastily. “I look back,” he says, “and…what’s the old Emerson quote? The years teach you what the days never know.”

He did not have any children of his own. “I never did. I love kids so much, I thought I would, but…The cool part is it’s freed me up to do things with kids that I wouldn’t have been able to do if I had my own. I try to be a real good uncle. I’ve got some nieces and nephews I love a lot and I try to be there for them. I was the guy who would show up at their grade school with the dog for Show and Tell Day. Whatever I could do. If grandma and grandpa couldn’t make it on the Special People Day, I’d travel to their schools.”

He also works with children, giving batting lessons — even into 2020. “I’ve always done that. John Verhoeven was my roommate in Triple A in Pawtucket. He came over from the Twins. Just a great guy. He called me up in the offseason after ‘82. I was done. He said he was going to open a batting cage, He said he would give pitching lessons. He thought people would pay for that. Nobody was giving lessons at the time. Now everybody’s doing it. He asked, ‘Would you like to try and do some hitting lessons?’ I said, ‘Yeah, let’s give it a shot.’ Within a few weeks, I was booked solid. I did 12 lessons a day, from 3 o’clock in the afternoon to nine o’clock at night. I had a new kid every half-hour.”

Even in the face of some significant health challenges later in life, he has remained an active and enthusiastic teacher. “That’s the one thing that keeps me sane. I love kids. I’ve always worked with them. There’s a little batting cage behind my buddy’s…in fact, I’m sitting there right now. In San Clemente. Dave Hansen and him put a couple of batting cages in the back of this house. He had a baseball store here, converted back into a house. We give lessons here to kids.”

Selling insurance paid well, but without a family he needed to support, he was free to pursue other callings — so he started printing t-shirts and then started writing movie screenplays.

“I ran that brokerage for about seven years. After that, I just decided I didn’t want to work in a suit. I hated the corporate world. My brother was a screen printer and I went and worked with him, just pulling the squeegee. Making t-shirts and stuff. I’ve always had a little ‘artiste’ kind of mentality. I never really knew it, though, because all I ever wanted to do was play baseball.

“I was sitting at a pizza place with my buddy’s wife Marilyn one day. They owned the pizza parlor. She was really a hysterical person. She goes, ‘I’m going to write some comedy stuff. Why don’t you help me? I think you’d be good at it.’”

“My cousin Dan, who’s a pretty established screenwriter, he had written a movie called Blind Justice that was on HBO. He gave me a copy of the script to read and I thought, ‘I think I could do this.’ So I actually wrote my first script — a baseball script about a mentally-challenged kid who lived underneath the center-field bleachers at Fenway Park with an old black guy who pitched in the Negro Leagues. The manager goes out one day to get his cigarettes from the dugout and he hears this loud noise. He goes out to investigate and he finds this kid, he’s winding up and pitching. There’s two batting tees — one low and outside and one up and in — with a cigarette pack sitting on top of each one of them and he picks off both the cigarette packs. It’s about how he joins the team and there’s a journeyman player on the team that he winds up affecting, who actually has the character arc in the story.

“Alcon Entertainment optioned it. A friend of a friend of a friend knew somebody who was the head of development for them. They optioned the script. In the meantime, I pitched an idea to them for what turned out to be Racing Stripes. It was in 2005. It was about a zebra that ran in the Kentucky Derby. Dustin Hoffman did a voice. And Whoopi Goldberg. It was live action but they had some CGI with the animals talking. I made enough money to keep going. I made almost a million dollars off of the movie. One day I walked out to my mailbox and there was a quarterly residual check for DVDs for $109,000. There was another check sitting there. It said ‘cast and crew.’ I had no idea what it even was. I opened it up and it was $92,000.

“At the time I thought I had it made. I had no bills and I had a nice car paid for and a place overlooking the Pacific Ocean and a couple of hundred grand in the bank. I didn’t know it but right about then I was getting lymphoma. I went through a rough time. Battled that for a couple of years. Basically lost everything. I came back and then I had some heart issues. But now I’m feeling really good.”

He is in full remission from cancer, but does have congestive heart failure and has a pacemaker in his chest.

Schmidt had been thinking about moving to northern Baja, in Mexico. He’s revamped the baseball screenplay and has another two as well. “I got paid to write the sequel to Racing Stripes but they never did anything with it. I’ve written a faith-friendly one — it’s not preachy — just faith-based. It’s about a female F-18 pilot who has a Bermuda Triangle-like experience. Like a cross between Top Gun and Contact. She’s kind of got a chip on her shoulder. She’s had a rough life and so her concept of God is…she doesn’t even want to talk about it. She’s got a squadron-mate, they call him Thumper because he’s a Bible thumper. She kind of has a revelation. She’s up in her Corsair with her instructor; she’s about ready to flunk out of the program. And they get hit by lightning. When they come out of a spin, there’s an old Navy Corsair on her wingtip. He’s got a tailhook on him. He’s lost at sea. He was up for an airshow. They let him land on the aircraft carrier and it turns out it’s the squadron mate of her grandfather who got lost at sea 50 years ago to the day. There’s a time-warp element in there, too. I’ve got high hopes for it. It’s called Never Too Lost.

“And I’ve got another one I wrote about a girl and a dog, kind of a real light-hearted one.”

Asked to look back on baseball, he says that at first life after baseball was very difficult. “The way it ended for me was so horrible that I just kind of got away from it. The first time I walked back into a ballpark was a couple of years after I got done playing. I was up at Anaheim Stadium and I walked through the tunnel and saw the field and I literally got nauseated. I almost threw up. It was traumatic for me, emotionally, the way it ended. At 22, I thought I had the world by the tail and then at 24, 25 I was done.”

He’s maintained a few friendships and was pleased to have had a call from sportswriter Peter Gammons just a week or two before the interview for this biography. “I told Peter the other day, when he called — it just kind of came out of the blue — I said, ‘You know, I never got to figure out how good I was.’”

It was disappointing to have worked so hard for so many years to get only a less-than-satisfying stay in the majors. Yet Schmidt has come to appreciate his experience. “I got to at least sniff it. I know guys who were better than me, especially pitchers, who never got the chance to even sniff it. Looking back on it now, I feel fortunate I even got in the little time I did.”

Last revised: June 29, 2020

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by James Forr and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Chris Bouton.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also relied on Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and the Encyclopedia of Minor-League Baseball.

Thanks also to SABR’s Rod Nelson and the Boston Red Sox.

Notes

1 Author interview with Dave Schmidt on April 25, 2020. Unless otherwise indicated, all direct quotations from Dave Schmidt come from this interview. Asked about his mother’s athleticism, he said, “Her brother Dick was quite a running back. He wound up going into the Navy and playing football there, but my mom — apparently — she was faster than he was. He was the star halfback at the high school, but they had a race one time and Mom beat him. She always said there was a guy who wanted to train her for the Olympics, but back then women didn’t do that. Her dad wouldn’t let her do it. She always regretted not having that opportunity.”

2 Eric Schmidt’s record can be found here: https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=schmid001eri

3 “I sucked at first base,” he says. “I couldn’t field a ground ball. They just stuck me out there because I could swing the bat. I was a center fielder until my junior year at high school. I could run. When I first signed, I could run a 6.7 60. I got timed at Anaheim Stadium. I could stay up with the outfielders, even the guys in pro ball. If you look at the stolen bases I had, one year I think it was 10-for-10. I had caught a couple of years in Little League but then I couldn’t catch anymore because of my knees. Growing pains. In high school, my coach said, “If you’re a catcher, you have a better chance to make it to the big leagues.” So I switched to a catcher my junior year in high school. I liked it. I was never really that natural. I got to be decent, but by the time I signed I had really only caught about 40 games in high school. I was pretty rough. I had a good enough arm at that point to get away with it. if the coach hadn’t suggested it, I would have never done it.”

4 He had, in the words of Peter Gammons, “found himself” and emerged from something akin to limbo. Peter Gammons, “Horner Ruling Benefited Players More Than Owners,” Boston Globe, June 10, 1979: 82.

5 Kelvin Moore had a higher batting average (.334) but did not have the required at bats. Schmidt’s On-base is identical with Jerry McDonald to three digits, but if it is extended, Schmidt’s is higher.

6 Associated Press, “Buffalo’s Lancellotti Selected EL’s MVP,” Hartford Courant, August 28, 1979: 48.

7 Peter Gammons, “Rookie Ratings: Only Few ‘Can’t Miss’,” Boston Globe, January 6, 1980: 52.

8 Larry Whiteside, “It’s the Same Story: Fisk Big Question,” Boston Globe, February 29, 1980: 35.

9 Associated Press, “Brisox’ Schmidt Signs 1-Year Pact with Boston,” Hartford Courant, March 2, 1980: 10C.

10 Larry Whiteside, “Schmidt Could Be Sox’ Sleeper,” Boston Globe, March 3, 1980: 31.

11 Larry Whiteside, “Allenson’s Bat Starts Talking,” Boston Globe, March 24, 1980: 31.

12 Ray Fitzgerald, “Goodbye, Pudgie,” Boston Globe, March 10, 1981: 57. The vertigo was understood to be an after-effect the beaning.

13 Ray Fitzgerald, “Goodbye, Pudgie.”

14 Tom Shea, “Schmidt Backs Up Sox in 7-4 Win,” Springfield Union (Springfield, Massachusetts), April 7, 1981: 21.

15 Peter Gammons, “Sox Found A Catcher Too Costly,” Boston Globe, April 3, 1981: 34.

16 Peter Gammons, “Rangers Drench Sox, 9-0,” Boston Globe, April 29, 1981: 71.

17 Joe Giuliotti, “Houk Sticks with Yaz,” Boston Herald, May 17, 1981: 49.

18 Associated Press, “Red Sox Clip Twins on Schmidt’s Home,” Hartford Courant, May 15, 1981: C1B.

19 Peter May, United Press International, “Second-Line Players Hunt for Extra Jobs,” Hartford Courant, May 27, 1981: D7B.

20 He would have been called up again after the June 11 game, since Gedman suffered a muscle pull in that game, but since there were no games to play due to the strike, Schmidt remained with the PawSox. Peter Gammons, “Gedman Doesn’t Think Thigh Muscle Torn,” Boston Globe, June 13, 1981: 26.

21 Joe Giuliotti, “Schmidt Feels Guilty Getting Paid in Minors,” Boston Herald, June 26,1981: 5.

22 Joe Giuliotti, “Schmidt Feels Guilty Getting Paid in Minors.”

23 Steve Harris, “Talkative Lickert Joins Sox,” Boston Herald, September 10, 1981: 5.

24 “The biggest influence in my whole career was Ted Williams convincing me to take the first pitch in every game. Ted used to talk to guys about that. He goes, ‘If you swing at the first pitch, you don’t know anything about the pitcher. If you take the first pitch, it’s like the 3-0 pitch where you totally relax. Everything comes into focus and you’re getting yourself set for the game. The worst case is it’s 0 and 1; you’ve still got two strikes left. If a guy throws you a breaking ball and misses, he’s probably going to come back with a fastball. Go ahead and take that. Now the worst case is you’re 1 and 1. You’ve seen his breaking ball. You’ve seen his fastball. And you’re still up there for your first at-bat.’

“I took that to heart and I think that was the big reason why I had such a great year in ’79. That was the last time I got 200 at-bats. I loved the guy. He would sit down there in a A-ball game, a minor-league game in spring training for 2 ½ hours, and talk hitting. He was so available.”

25 Garry Brown, “Non-roster catcher LaFrancois Good Bet to Make Sox Roster,” Springfield Union, March 27, 1982: 21. As it happens, LaFrancois stuck with the Red Sox all season long, but only got into eight games and only has 10 at-bats. He hit .400 and earned status as a trivia question: Name the last major-league position player to spend a full season on the big-league roster and hit. 400.

Full Name

David Frederick Schmidt

Born

December 22, 1956 at Mesa, AZ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.