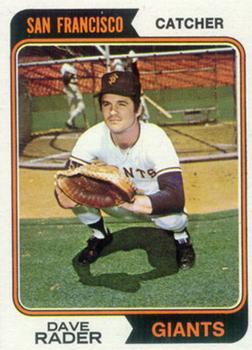

Dave Rader

In 1990 an old-school scout, Dick Wilson, stated that it was hard to explain that intangible something that told him a player had what it took to be a major-league player, but he “knew it when he saw it.” About Dave Rader, Wilson relayed, “I saw him at South Bakersfield High School, and I knew right away he was a winner. He had that look; he feared nothing. Then I talked to him afterward, and it just reinforced my opinion.”1

In 1990 an old-school scout, Dick Wilson, stated that it was hard to explain that intangible something that told him a player had what it took to be a major-league player, but he “knew it when he saw it.” About Dave Rader, Wilson relayed, “I saw him at South Bakersfield High School, and I knew right away he was a winner. He had that look; he feared nothing. Then I talked to him afterward, and it just reinforced my opinion.”1

Rader became a first-round draft pick in 1967. He went on to play 10 years in the major leagues (1971-80) for five teams with a career .257 batting average. He is thought of as a journeyman catcher from the 1970s. Yet even though he was never inducted into Cooperstown, Rader is in two other Halls of Fame. This not-so-insignificant player was also a Sporting News Rookie of the Year.

David Martin Rader was born on December 26, 1948 to Porter “Martin” Rader and Delvia (née Sellers) Rader in the small Northeastern Oklahoma town of Claremore. He was part of a blended family with two older half-siblings and three full siblings. He grew up living a typical, small-town life of the 1950s consisting of school, youth baseball, 4-H Club, and Cub Scouts.2

In 1964 Rader’s father — a plumber — moved the family from Claremore to Bakersfield, California, hoping to find to find a more economically viable city in which to raise his family. Bakersfield was known for its large community of transplanted Oklahomans.

Rader told journalist Bob Broeg that his older half-brother, Benny Griffith, “caught in the Cardinals’ organization and taught him the wisdom of putting on the so-called tools of ignorance to get somewhere in baseball.”3 Rader played for Bakersfield Post No. 26 American Legion team, which primarily comprised Bakersfield Junior College players and a few high school students.4

Dave attended South High School in Bakersfield. He played both football and baseball. In 1966 he was named all-city quarterback and received All-Star honors in baseball.5 He was awarded the Sam Lynn Trophy as outstanding senior athlete in 1967 and the Harry Coffee Award in both 1966 and 1967 for outstanding player in football. In view of his gridiron success, he was surprised to be drafted in baseball.6

That June 6, in the first round of the 1967 major-league amateur draft, Rader was picked 18th overall by the San Francisco Giants. He signed on June 14, 1967 for a $40,000 bonus, which he said was “a lot of money for an Okie.”7 Rader was selected after fellow catchers Johnny Jones (Senators) and Mike Nunn (Angels) — neither of whom ever made it to the majors — and future Hall of Famer Ted Simmons (Cardinals). Rader eventually backed up Simmons for a year in 1977.

Rader spent five years climbing up the Giants’ organization. He began his professional career with the 1967 Salt Lake City Giants in the Pioneer League under manager Harvey Koepf. After batting .321 with 18 RBIs, he was promoted in midyear to the Fresno Giants of the California League. Under the management of Dave Garcia, he played in 18 games, getting 11 hits over 46 at-bats.

The spring of 1968 found Rader still with Fresno. He caught 74 of the 138 scheduled games platooning with minor-leaguer Jerry Muse. A local reporter seemed to champion the undrafted Muse over the younger Rader.8 However, Rader had an advantage in that the Giants had more invested in their first-round pick. He also outhit Muse, .245 to .220, with seven additional extra-base hits.

Rader also got married that year, to Betty L. Moshier in Bakersfield on June 20. The couple settled in Fresno.

The 1969 season began with a promotion to the AA affiliate Amarillo Giants. Rader struggled as one of the younger players on the team. His average suffered (.203) as he prioritized managing a pitching staff. These were the days before the home run was king and even Rader was surprised when he supplied an occasional homer. After a game against the Shreveport Braves, Rader said of a rare long ball, “When I hit it, I knew it was going out, but it was just luck because I’m not going to hit many homers.”9 He hit six of them in 1969.

Rader’s performance earned him an invitation to spring training in 1970.10 After camp, he returned to Amarillo, playing in 92 games, and hitting .241 with 10 home runs. He shared catching duties with Mike Sadek, who backed up Rader in San Francisco off and on from 1973 to 1976.

For the 1971 season, Rader was assigned to the AAA Phoenix Giants. Again, Rader and Sadek platooned at the catching position. Rader’s bat heated up in the Arizona desert. In 85 games, he batted .314 with eight home runs and 47 RBIs. This was enough to earn him a debut appearance with the Giants on Sunday, September 5, 1971 in San Francisco, hosting the Houston Astros. In the back end of a doubleheader, Rader pinch-hit in the sixth inning for relief pitcher Don McMahon and grounded out to first base. It was his only plate appearance in that game (he was removed in a double switch). Rader appeared twice more for the Giants over the remainder of the season, going hitless in three at-bats.

During his third Giants training camp in 1972, “Rader’s fortunes took a good turn in mid-March during spring training. His wife gave birth to a seven-pound boy that made him a proud papa for the first time and on the same day [manager] Charlie Fox told him he won a catching job with the Giants.”11 Jack Hanley of the Independent Journal apparently did not know of the existence of Rader’s three-year-old daughter. However, the San Francisco Examiner’s Bucky Walter attributed the birth of the baby boy and Rader’s first Giants home run to Doug Rader, third baseman for Houston. It was a battle of recognition that Dave Rader fought the rest of his career.12

Expectations for Rader’s career were high. Fox praised Rader’s “bulwark of strength behind the plate and his bat” and “his ability to stop low pitches.”13 A home state journalist with the Sacramento Bee, Tom Kane, even attempted to conjure a comparison with Johnny Bench.14 But Rader’s slight build (5-11, 165 pounds) stood in contrast to the burly Bench.

Rader played in 133 games during his rookie year, batting .259 with six home runs. His first regular season major-league home run came off future Hall of Famer Tom Seaver. He finished a distant second to Jon Matlack in the Baseball Writers’ Association of America NL Rookie of the Year Voting for the 1972 season, receiving only four votes to Matlack’s 19. However, Rader did win The Sporting News NL Rookie Player of the Year Award.15

In 1973 Rader played in 148 games as the number-one catcher for the Giants. It was his best year in terms of fielding percentage. Early in the year, he made a rare — especially for a catcher — unassisted double play. It came against the Braves on April 18. In the 11th inning, Sonny Jackson was on second base when Braves pitcher Tom House popped up a bunt attempt. In a heads-up play, Rader pounced from behind the plate and caught the ball before it hit the ground. Jackson did not realize the catch had been made and kept going to third. Seeing second base unoccupied, Rader ran to the bag.16

That play wasn’t Rader’s only rarity of the year. Just weeks later, on May 27, he hit an inside-the-park home run at Candlestick Park. Like most catchers, Rader was not known for speed. For example, he stole just eight bases in the majors.

But his performance at the plate suffered; his average never got above .250 after Opening Day and slipped to .229 for the year. Surprisingly, Rader’s best matchup was against Cardinals pitcher Bob Gibson. In Rader’s 31 at-bats against “Hoot,” he hit .484. In their third meeting during the season, Rader got a third inning double off the future Hall of Famer. Later in the eighth inning, he commented on Gibson’s earlier popup and Gibson beaned him in the side of his helmet. Gibson denied hitting Rader intentionally, dodging further questions by reporters saying, “This is like a family feud and I don’t want to talk about it.”17

In early 1974, contract negotiations were somewhat disappointing for Rader. The Giants, after praising his catching the year before, suggested that he could be traded to another team, viewing his skills as more in line with those of a second-string catcher. Though Rader conceded that his hitting had not been up to par, he had only five passed balls during the 1973 season. Of catchers with 100 games, only Joe Ferguson, Johnny Bench, and Randy Hundley had better fielding percentages.18 Rader did not go into training camp during negotiations. The Giants first offered him a contract that included a pay cut.19 He responded that he could work in real estate instead of being a catcher.20 This was not an idle threat — he had often worked in the offseason, and during his time with the Giants, he finished two years of college, formed a concrete company, and held a real estate license.21

Reinforcing the perception that Rader was not worthy of the top catching job, the Giants obtained two veteran receivers: Ken Rudolph from the Cubs and John Boccabella from the Expos. Rudolph along with Boccabella caught 44 percent of the innings in 1974. Rader did not start a game until the third week of the season and started in only 88 that year. The reduction in playing time proved good for Rader’s bat, though — he hit a healthy .291 to lead the faltering Giants team in hitting. Halfway through the season, manager Charlie Fox was out, and Wes Westrum was in.

Despite his offensive success the previous year, respect remained elusive for Rader in 1975. Another new catcher, Marc Hill, was acquired from St. Louis in exchange for Rudolph and Elias Sosa. Hill was 6-foot-3 and 205 pounds, everything Rader was not. He’d been scouted by Westrum — himself a former big-league catcher — for two years. In Westrum’s opinion, Hill was “just as good as Johnny Bench.”22 While Hill was younger and better defensively, his home run displays in batting practice rarely carried over to games. Rader still started 80 games to Hill’s 47 and Sadek’s 33.

Rader recalled that one of the biggest highlights of his career was catching Ed Halicki’s no hitter against the New York Mets on August 24, 1975.23 It was the second half of a doubleheader. The Giants took a two-run lead in the first inning and eventually won 6-0; Rader helped the cause with two runs on one hit and one walk. The Mets had only three baserunners, on an infield error — a somewhat controversial scoring decision — and two walks.

During the game, Halicki experienced some stiffness in his shoulder and “told Rader not to be afraid to call the change. If I was going to do it, I was going to do it with my best stuff — the fastball and the slider. But I had a good change.”24 Halicki praised Rader’s game calling and “Rader was as thrilled as Halicki because this also was the first no-hitter he ever caught.”25

December 1, 1975 was the beginning of the end of Horace Stoneham’s ownership of the Giants. When Stoneham defaulted on a $500,000 loan from the NL, the league took over administration of the team. Wes Westrum and the rest of the team’s coaches had already been dismissed in November to allow the new owners to hire their own on-field management. The last-minute, hastily organized new team ownership rehired Bill Rigney on March 3, 1976.26

When spring training started, Rader again did not have a contract.27 Rigney, at first, did not deviate much from the 1975 lineup, platooning Rader with Sadek and Hill. At the beginning of September, however, the Giants promoted Gary Alexander from Triple A. The rookie started in 22 of the last 28 games, including both games of a doubleheader versus Cincinnati. Rader started only five games in the same period.

On October 20, 1976, after five seasons with San Francisco, the Giants traded Rader to the St. Louis Cardinals along with Mike Caldwell and John D’Acquisto for Will Crawford, John Curtis, and Vic Harris. In an interview with Bob Broeg, Rader said he was “apprehensive at first about the trade because I wanted to play every day, but then I thought about it more and besides, [manager] Vern Rapp has said everybody would play and that he’d use his bench. So now I am looking forward to helping in any way the club thinks I can.”28

In April 1977, Rader’s wife, Betty, was hospitalized in California because of an aneurysm. He missed 12 days with the team to be with her. Starting catcher Ted Simmons, however, played through an injury which was healed before Rader returned.29 After his return, Rader was used sparingly by the Cardinals, starting in just 23 games and logging only 114 at-bats. Playing behind Simmons proved to be an easy job—at least physically. Simmons’ formidable bat kept Rader on the bench regularly. With Simmons’ versatility as a switch-hitter and .318 batting average, there was little room for Rader’s left-handed bat.

Despite Rader’s request to be traded to a West Coast team to work on his struggling marriage, St. Louis traded him to the Cubs that December along with Heity Cruz for Jerry Morales, Steve Swisher, and a player to be named later. But even though he was divorced from Betty in 1978, his fortunes on the field began to look up that spring as the Cubs gave him the opportunity to be their number one catcher.30

Rader’s year with the Cubs started off successfully enough. As the everyday starting catcher, his average hovered around .250. By the end of May he had struck out just eight times, with 12 RBIs, including four in one game against his former St. Louis teammates with a single and a triple. Yet with his competitive attitude, it was not enough. In an interview with Chicago Tribune writer Richard Dozer, Rader said, “I’m happy I’ve had some big hits lately, but I’m disappointed in my batting average.”31

On June 26, 1978, Rader got his only career grand slam as a pinch-hitter against New York Mets pitcher Dale Murray. Murray pitched a fastball “nice and high… It felt good as soon as I hit it. I could tell it was a home run.” But as he also admitted, “I got a little help from the elements. Without that wind blowing out, it wouldn’t have made it.”32 As one may infer, the game took place at Wrigley Field.

By the beginning of August, though, Rader’s average had cooled to a paltry .211. But batting was not his only problem; he had 11 errors in 775 1/3 innings during the season, a total matching only his rookie year, when he played a good deal more (1,076 1/3 innings). Rader had lost his starting catcher job to Tim Blackwell, a free agent acquisition, earlier in the year. In August and September, he started in only 19 games. In mid-August, the Cubs were only two games out of first place in the NL East, but that was as close as the team got. By mid-September, they were eight games behind the Phillies and the Pirates.

On February 23, 1979, the Cubs and Phillies completed an eight-player mega-deal that had taken weeks to negotiate. Rader, Manny Trillo, and Greg Gross were traded for Derek Botelho, Barry Foote, Jerry Martin, Ted Sizemore, and minor leaguer Henry Mack. Cubs executive vice president Bob Kennedy viewed the trade as beneficial: “Were we going to have any chance of catching the Phillies with Rader as our regular catcher and with Sam Mejias and Scot Thompson platooning in center field? Be serious!” Referring to Foote, Kennedy said, “Now we have a quality catcher.”33

After a tough year of working hard, trying to make a difference, and swallowing his pride, Rader still wanted to play. “‘I don’t want to be traded,’ he said. ‘Not really, not after being traded so much. I know that might sound as though I’m backing up on what I said before, but it’s not. I do want to play. But I want to play for the Phillies. … I love this game. It’s the best thing you can do without working.’”34 As it developed, though, Rader played behind catchers Bob Boone and veteran left-handed hitter Tim McCarver. He appeared in only 31 games that year.

Rader also remarried in 1979, to Karen L. Schroeder in 1979. He and his second wife did not have children.

The Phillies’ trade with the Cubs helped them win just their third NL pennant and first World Series in 1980. Trillo and Gross were big contributors, with impressive postseasons. However, Rader wasn’t there to enjoy it — during spring training he was dealt to Boston for a player to be named later and cash.

Red Sox general manager Haywood Sullivan wanted Rader because he was “experienced, a battler and was available cheap.”35 Again, Rader would be a part-time backup catcher if Carlton Fisk’s shoulder became a problem — and he would platoon with right-handed Gary Allenson if Fisk were out.36 At 31, Rader was pragmatic about his situation. “Oh, well, it’s a funny thing about this game. The only thing I never figured out was how to hit…no one forced me to sign my first contract with San Francisco. My father wanted me to be a plumber. Sometimes I’m a better plumber than I am a player.”37 Ironically, after years of struggling at the plate, it was his best offensive year ever. In 137 at-bats, he hit .328 with three home runs and 17 RBIs. Rader caught in only 34 games, starting in 27.

At the end of the season, Rader’s name was added to the list for the November 13 re-entry draft for free agency. He was among the 20 players of the 48 free agents that did not receive the minimum of two team drafts. He was free to negotiate with all 26 teams.38

The 1981 season began amid rumors of a strike over free agency and compensation. Dave Skaggs was released by the Angels after he filed for arbitration and the team picked up Rader. But then, on April 8, 1981, he was designated for assignment.

Rader was a practical man; he’d learned how to work with his hands in the tradition of his rural Oklahoma roots. His earlier years working and studying in the off-season finally paid off. After 14 years in baseball, Rader did indeed become a plumber, as were his father and grandfather before him. He and his second wife, Karen, were also active in real estate and mortgage lending.

In 1987, Rader was inducted into the Bob Elias Sports Hall of Fame in Kern County, California, of which Bakersfield is the county seat. Other inductees include NASCAR driver Casey Mears, NFL quarterback David Carr, and WNBA point guard Nikki Blue.39 Rader was also inducted into Bakersfield’s South High School Hall of Fame in 2016.40

Dave Rader is often remembered as “That Other Guy” in the Phillies’ trade for Manny Trillo and Greg Gross. They played while he moved into “the dugout’s Oblivion Suite.”41 If he was not forgotten, he was often confused with Doug Rader. But in 2012, John Grisham wrote a New York Times bestseller, Calico Joe, A Novel, about a fictional rookie phenom. It was set in 1973 against a backdrop of real players. Rader is briefly mentioned in Chapter Four. “The Giants catcher, Dave Rader, had the ball and, when the dust settled, called time. Slowly, he walked past the mound to second base, where he ceremoniously handed it to Joe Castle. The crowd roared even louder with this memorable act of sportsmanship.”42 In the final analysis, what a unique way to be remembered.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank fellow SABR members Glenn Guzzo, Jim Moyes, and Charles Slavik for their review and suggestions for the improvement of this biography, which was further reviewed by Bill Nowlin and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Evan Katz.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also relied on Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and Ancestry.com.

Notes

1 Tim Keown, “In Search of the Next Babe Ruth,” Sacramento Bee, March 27, 1990: D5.

2 See “David Radar [sic] New 4-H Club President,” Claremore Daily Progress (Claremore, Oklahoma), April 13, 1961: 7 and “Cub Scouts Activities,” Claremore Daily Progress, April 17, 1958: 7.

3 Bob Broeg, “Cards Hope Rooster Rader Is Catcher To Crow About,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 4, 1977: 6C. This author was unable to find any written evidence to support or refute that Mr. Rader’s half-brother, Benny Griffith, played in the Cardinals organization or in any professional baseball organization.

4 “Bakersfield Semi-Pros Bring SF Giants Top Draft Pick,” Santa Maria Times, June 7, 1967: 23.

5 Tom Kane, “SF’s Rader Has Become An Asset Behind The Plate,” Sacramento Bee, July 13, 1972: 63.

6 Video Memories, “2016 Dave Rader,” June 21, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LtYW0yS–as.

7 Broeg.

8 Gerald Merrell, “Three-Run Ninth Inning HR Topples Visalia 5-3,” Hanford Sentinel (Hanford, California), April 25, 1968: 8.

9 Jim Sims, “A-Giants Win; 2 1/2 Out of Lead,” Amarillo Globe-Times, June 11, 1969: 44.

10 “Seven More Giants Sign; Total of 34 Is in Camp,” Sacramento Bee, February 6, 1970: E5.

11 Jack Hanley, “Rader Shows He’s A Major Leaguer,” Daily Independent Journal (San Rafael, California), May 23, 1972: 30. Rader’s first child, daughter Shelly, was born in 1968. His son David Lance, mentioned here, later died in a 2002 motorcycle accident.

12 Bucky Walter, “Big Day for Rader – Barr Rapped in 6-5 Loss,” San Francisco Examiner, March 13, 1972: 49.

13 Tom Kane, “SF’s Rader Has Become An Asset Behind The Plate.”

14 Tom Kane, “SF’s Rader Has Become An Asset Behind The Plate.”

15 Baseball Almanac, n.d., “Rookie Player of the Year Award by The Sporting News,” Accessed August 10, 2020, https://www.baseball-almanac.com/awards/aw_snrp2.shtml.

16 “Catcher’s Unassisted Double Play Sparks Giants’ Victory,” York Daily Record (York, Pennsylvania), April 19, 1973: 56.

17 Tom Kane, “Fireballing Gibson Halts Giants; Cards Win 3-2,” Sacramento Bee, July 7, 1973: 17.

18 Jack Hanley, “Giants Rader is ‘Confused’,” Times (San Mateo, California), March 14, 1974: 23.

19 Bucky Walter, “Giants running out of catchers,” San Francisco Examiner, February 25, 1974: 49.

20 “Pete Rose gets tough at barganining table,” Redlands Daily Facts, February 26, 1974: 11.

21 Broeg.

22 Dick Draper, “Giants Pilot Erases Old Memories,” Times (San Mateo, California), February 6, 1975: 17.

23 Broeg.

24 Augie Borgi, “Halicki 0-Hits Mets, 6-0, for Giant Split,” Daily News (New York, New York), August 25, 1975: 45. –

25 Jack Hanley, “Halicki No-Hits NY Mets 6-0,” Sacramento Bee, August 25, 1975: C1.

26See Andrew Goldblatt, The Giants and the Dodgers, Four Cities, Two Teams, One Rivalry (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2003), 221 — 225, and Kent Johnson, “Giants Fire Westrum, Staff; Club Sale Reported Near,” Sacramento Bee, November 20, 1975: D1.

27 Glenn Schwarz, “Giants, A’s slow on the draw in Cactus League,” San Francisco Examiner, March 18, 1976: 53.

28 Broeg.

29 Dick Kaegel, “Rader Catches Up With Cards In Philly,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 24, 1977: 41.

30 “Catcher Dave Rader has found a bit of heaven with the Cubs,” Detroit Free Press, April 21, 1978: 4D.

31 Richard Dozer, “Cubs pad lead with 6th in row; Roberts, Rader rip Cardinals,” Chicago Tribune, May 27, 1978: 59.

32 Cooper Rollow, “Rader slam blasts Mets,” Chicago Tribune, June 27, 1978: 45.

33 Dave Nightingale, “Martin, Foote come to N. Side,” Chicago Tribune, February 24, 1979: 75.

34 Jayson Stark, “Dave who? You know, the…uh…,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 24, 1979: 23.

35 Peter Gammons, “Sox Acquire Rader,” Boston Globe, April 1, 1980: 43.

36 Gammons.

37 “Rader feels he can bolster thin catching ranks,” Boston Globe, April 2, 1980: 59.

38 KCSports. Accessed August 5, 2020. http://kcsportshalloffame.org/inductees/

39 “Sox Show Little Draft Interest,” Hartford Courant, November 14, 1980: C1. According to Baseball-Reference.com, the free agent reentry draft lasted from 1976 to 1981. The purpose was to limit the top players’ bargaining leverage by restricting the number of teams who could draft and thereby negotiate with them. It also prevented the lower level players of being held hostage to negotiating with one team by letting those players negotiate with any-and-all teams if they were drafted by fewer than four teams, https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Free_agent_reentry_draft.

40 Video Memories, “2016 Dave Rader.”

41 Stark.

42 John Grisham, Calico Joe, A Novel (New York: Dell, a division of Random House, 2013), 39.

Full Name

David Martin Rader

Born

December 26, 1948 at Claremore, OK (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.