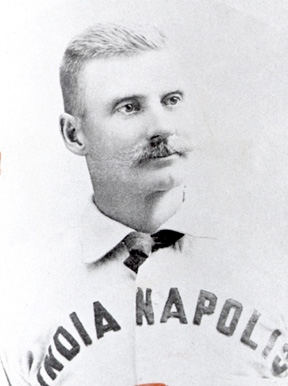

Jack Glasscock

John Wesley “Jack,” “Pebbly Jack” Glasscock is considered by many to have been the best shortstop of the nineteenth century, earning him the accolade “King of the Shortstops.” His contemporary, Al Spink, founder and editor of The Sporting News, wrote of Glasscock “he was acknowledged by all his fellow players to be the greatest in [sic] his position” and “one of the greatest players from a fielding standpoint the game has ever known.” (Spink, 220) Current sabermetrician Charles Faber rates Glasscock the best shortstop of the nineteenth century. (Faber, 79)

John Wesley “Jack,” “Pebbly Jack” Glasscock is considered by many to have been the best shortstop of the nineteenth century, earning him the accolade “King of the Shortstops.” His contemporary, Al Spink, founder and editor of The Sporting News, wrote of Glasscock “he was acknowledged by all his fellow players to be the greatest in [sic] his position” and “one of the greatest players from a fielding standpoint the game has ever known.” (Spink, 220) Current sabermetrician Charles Faber rates Glasscock the best shortstop of the nineteenth century. (Faber, 79)

In his later years, Glasscock boasted that he had lived his entire life at 9 Maryland Avenue in Wheeling, West Virginia. Born there on July 22, 1857, his Scotch-Irish parents, Thomas Glasscock and Julia A. Collett, named him for the father of Methodism, even though he would attend St. Luke’s Episcopal Church until his death. After attending Madison Elementary School through the fourth grade, he dropped out of school to become a carpenter like his father, but he did take some correspondence courses.

Baseball quickly became his vocation. At 15 he played for the Buckeye Base Ball Club, one of ten amateur teams in the Wheeling area. Before the 1875 season ended, Glasscock, along with Sam Barkley and Sam Moffet, two other teenage Buckeyes who eventually played in the majors, joined the Standards, the top club of Wheeling. In 1876 he hit .369 for the Standards. In 1877 the Standards became an independent professional team, the first pro team in West Virginia. The team paid Glasscock $40 a month to play third base.

Before the summer of 1877 ended, Glasscock, still a teenager, left home to play for more money than he could make in Wheeling. He left with a barnstorming team called the Stars but soon joined the Champion Club of Springfield, Ohio. The next summer found him in Pittsburgh with the Alleghenys of the International League. When that club disbanded in June, he and teammate George Strief caught on with an independent professional team in Strief’s hometown of Cleveland called the Forest City Club.

In 1879 Cleveland entered the National League. Glasscock became the first native of West Virginia to play in the big leagues. He was still a growing teenager, standing 5 feet, 8 inches and weighing 160 pounds, but he filled out to 5’10” and 175 pounds at the height of his career. He threw and hit right-handed. His rookie season, split between second and third base, offered little promise as he batted a paltry .209.

Glasscock switched to shortstop in 1880 and became the pivot of one of the top infields of the 1880s. With “Silver Bill” Phillips at first, and Fred Dunlap playing second they earned the nickname of “Stonewall infield.” Spink remembered it as “perhaps the greatest infield ever known.”(Spink, 196) Faber rates the trio as the best double play combo of the 1880s. (Faber, 48) In 1881 Glasscock led shortstops in putouts, assists, and fielding average. He followed up leading the NL in assists and double plays in 1882 and fielding average in 1883.

In 1883 he reached star level. Batting third in the Blues’ order, he tied Tom York for the team in runs batted in. He also pushed his hitting near .290. That, combined with his great fielding led Faber to rate him player of the year for 1883.

When the short-lived Union Association claimed major league status in 1884, first Dunlap and then Glasscock jumped to the new league. Robert L. Tiemann quotes Glasscock as saying “I have played long enough for glory, now it is a matter of dollars and cents.” (Tiemann, 51) Tiemann claimed the Cincinnati Unions paid him $2,000 for the remainder of the season, a big jump from his $1,800 Cleveland salary, but Glasscock remembered his Cincinnati salary was $1,600 for the part of the season he played there. (Glasscock, 2) He batted .419 against inferior pitching. While with Cincinnati, sportswriter Harry Weldon gave Glasscock the nickname “Pebbly Jack” for his habit of picking up stones in the infield and tossing them away. (Lanigan)

Following the collapse of the Union Association, the National League assigned Glasscock to the St. Louis Maroons for 1885. They were a bad team, but he flourished in the two seasons he played in St. Louis. The Maroons paid him handsomely, $2,200 in 1885, and made him captain. Glasscock rewarded them by hitting over .300 for the first time with a .325 average in 1886. He set NL records with 397 assists in 1885 and double plays in 1886. Appreciative St. Louis fans presented him with a diamond stick pen. (Glasscock, 3)

After the Maroons folded following the 1886 season, sports pages were filled with conjecture about which team would land him. The Sporting News speculated, “he will get the largest salary ever paid a player.” (TSN, 4/8/1887) Glasscock claimed Boston offered $7,500 for him (Glasscock, 3), but, of course, the League wanted no free agents and transferred the St. Louis players to Indianapolis.

Glasscock’s career peaked in his three seasons with the Hoosiers. His fielding continued to excel. He set new major league records for assists and double plays in 1887, and again led the league in fielding in 1888. The following year he set new marks with 246 putouts and led the league in assists, double plays and fielding average.

The 1889 season was Glasscock’s finest. Faber believes he was the major league player of the year that season. He led the majors with 205 hits, and finished second in batting with a .352 average, the highest yet achieved by a shortstop. He ranked second in doubles and total bases, while scoring 128 runs and stealing 57 bases. He even took over as manager. The Hoosiers had a deplorable 25-43 record when he took over. Under his prodding they won 34 games against 32 losses. Despite the team’s success he did not enjoy managing and never managed again.

Personally, the Indiana experience created considerable stress for Glasscock. Sporting Life reported him “anxious…to get away from Indianapolis” (SL, 9/28/1887) in June 1887, and still “not satisfied here”( SL, 9/28/1887) in September. Back home in Wheeling, he was jailed for being drunk and disorderly. As manager he drove his players and baited and bullied umpires. A Sporting Life reporter wrote “I have heard [him] swear and act like a blackguard before and [sic] audience partly composed of ladies.” (SL, 3/2/90)

Unfortunately for Glasscock the Brotherhood war came at the peak of his career. Unlike 1884 when he had been one of the few established players to jump to the Union Association, he stayed with the National League. In doing so he engendered considerable animosity among the Brotherhood members. Indeed, in November 1889, after first agreeing to support the Brotherhood, then re-signing with Indianapolis, the Brotherhood expelled him. (TSN, 11/18/1889)

Because so many players jumped to the Players’ League in 1890, Glasscock’s accomplishments that year have been downplayed. After Indianapolis lost its franchise, Glasscock was transferred to New York. With the Giants he won his only major league batting championship, hitting .336 for the 1890 season. He again led the league in hits, the first time anyone had led in back-to-back years, while also tying a record with six hits in six at bats in one game.

In 1891 he injured his hand and was never the player he was before. He fielded well again in 1893, but he could not throw as he once did. He could still hit, as his .320 average and 100 plus RBIs in 1893 attested. Transferred to Washington, the Nationals released him in 1895 midway through his seventeenth season.

Glasscock was the most difficult batter of his day to strike out. In his career he struck out only once every 33 at bats. In 1887 and 1890 he struck out only eight times. It would be 35 years before Joe Sewell bettered his 1890 average of 64 at bats per strikeout.

After Washington released him, Glasscock returned to Wheeling where he caught on with Ed Barrow’s team in the Iron and Oil League. Batting over .400, he led his hometown team to the league championship. It was Barrow’s and Glasscock’s first pennant.

Glasscock continued to play in the minor leagues as a first baseman until 1901. He topped the Western Association in 1896 with a .431 average. After three seasons with St. Paul, he finished up with Fort Wayne, Sioux City and Minneapolis.

When he finally hung up the glove he never adjusted to wearing, he retired to Wheeling. He and his wife Rhoda Rose Dubla, who died in 1925, raised two sons, John T. and Eugene, and a daughter, Florence. Glasscock made a living as a carpenter.

Glasscock died of a stroke in 1947 and was buried in Greenwood Cemetery in Wheeling. He was inducted into the West Virginia Hall of Fame in 1987.

Sources

Akin, William E., “The King of the Shortstops,” The West Virginian 1, August 1977), 24-27.

Faber, Charles F., Baseball Pioneers: Ratings of Nineteenth Century Players. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Co., 1997.

Glasscock, Jack, “Autobiography of Jack Glasscock,” Cycleback Museum of Early Baseball Memorabilia (www.cycleback.com).

Goewey, Ed A., “The Old Fan Says,” Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly, October 23, 1913, 394.

Horton, Robert L., “Baseball’s Best Fielding Shortstops,” Oldtyme Baseball News 9 (1998), 38.

Huff, Doug, “W. Va. Hall to Induct Wheeling’s Glasscock,” Wheeling Intelligencer, April 22, 1887, 19.

Lanigan, Harold W., “Jack Glasscock, 81, Recalls His Days of Fun and Fame as Barehanded Shortstop on Pebbly Diamonds,” The Sporting News, April 24, 1941.

“Obituary,” Wheeling News Register, February 25, 1947.

Phelps, Frank V., “Glasscock, John Wesley ‘Jack,’ ‘Pebbly Jack,’” in David L. Porter (ed.), Biographical Dictionary of American Sports: Baseball, Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1989, 216-217.

Spink, Alfred H., The National Game. 2nd edition, Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2000 (original 1910).

Tiemann, Robert L., “John Wesley Glasscock,” in Robert L. Tiemann and Mark Rucker (eds.), Nineteenth Century Stars. Cleveland, SABR, 1989, 51, 143.

The Sporting News, 6/19/1980; 1/20, 2/27, 4/10/1887; 11/18, 11/18/1889.

Sporting Life, 1/26, 3/1, 6/8, 9/28/1887; 11/18, 11/25/1889; 3/2, 7/5, 7/19, 9/27/1890; 4/20/1892.

Full Name

John Wesley Glasscock

Born

July 22, 1857 at Wheeling, WV (USA)

Died

February 24, 1947 at Wheeling, WV (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.