Roy Henshaw

Roy Henshaw never let his height, or lack of it, derail his dream of becoming a big leaguer. Standing just 5-feet-8, the southpaw hurler jumped from the University of Chicago straight to the Chicago Cubs in 1933. Two years later he went 13-5 as a valuable swingman, helping the North Siders capture the pennant. That season proved to be the highlight in Henshaw’s eight-year career (1933, 1935-1938, 1942-1944), during which he went 33-40 with four teams.

Roy Henshaw never let his height, or lack of it, derail his dream of becoming a big leaguer. Standing just 5-feet-8, the southpaw hurler jumped from the University of Chicago straight to the Chicago Cubs in 1933. Two years later he went 13-5 as a valuable swingman, helping the North Siders capture the pennant. That season proved to be the highlight in Henshaw’s eight-year career (1933, 1935-1938, 1942-1944), during which he went 33-40 with four teams.

Roy Kniklebine Henshaw was born on July 29, 1911, in Chicago. His parents were Raymond Stevens, a native Illinoisan, and Lillian (née Kniklebine) Henshaw, originally from Michigan, where her parents had settled after emigrating from Germany. The Henshaws married in 1908 and raised three children (Roy, Chere, and Jewel) in Chicago’s upper middle-class South Shore neighborhood, where they owned the R.S. Henshaw newspaper delivery business. Always small for his size, Roy was attracted to baseball, basketball, and tennis, which allowed him to use his agility and speed as an advantage. According to one widely reported story, the ambidextrous Henshaw batted and wrote with his right hand, but learned to pitch left-handed because his father was an admirer of Rube Waddell, a standout southpaw for the Philadelphia Athletics in the first decade of the 20th century.1 Henshaw played baseball at Bowen High School, graduating in 3½ years.

Henshaw attended the University of Chicago, where he blossomed into an All-American after almost quitting the sport as a freshman. During the Maroons’ journey to Japan to play local college teams in September 1930, the teenage hurler struggled, and confided to coach Nelson Norgren that he intended to end his baseball aspirations.2 The following season, under new coach Pat Page, a former three-sport star on the university’s Big Ten championships teams in baseball, basketball, and football two decades earlier, Henshaw unexpectedly emerged as one of the best hurlers in the country in 1931. Supposedly yielding an average of just four hits per game, Henshaw won nine games, including twice hurling complete games to win both games of a doubleheader, against the University of Michigan and Indiana University.3 The Associated Press hailed Henshaw as the “greatest sensation that the Big Ten conference has ever known.”4 Defying his small, 150-pound stature and an underhand pitching delivery, Henshaw was a strikeout artist, regularly registering 10 punchouts or more in games in 1932, including an eye-catching 65 in his last four starts.5 Growing up and attending college on the south side of Chicago, the domain of the White Sox, Henshaw had followed the American League for years. He worked out for his hometown club, as well as the New York Yankees, Philadelphia A’s, Washington Senators, and Boston Red Sox. After hurling batting practice for the Chicago Cubs in 1932, Henshaw signed in October with the North Siders, who supposedly offered him the best contract. More than anything, Henshaw wanted to skip the minors and start in the majors. His chances with the Cubs seemed to be good, as right-handers had started all 154 games for the Cubs that season. Anticipating eventually taking over his father’s business, Henshaw graduated with a degree in economics. In 2003 he was posthumously inducted into the University of Chicago’s athletic hall of fame.

Even though he was described as “little more than a prospect [who] isn’t likely to be with the [Cubs] when the season opens,” Henshaw had a productive spring training on Catalina Island, and surprisingly made the team in 1933.6 Newspapers praised the hurler’s “remarkable fastball for his build,” capable curve, and good change of pace.7 Henshaw debuted in a relief appearance on April 15, retiring all three batters he faced in the ninth inning in a loss to the Cincinnati Reds. While skipper Charlie Grimm once again sent right-handers (led by Guy Bush, Pat Malone, Charlie Root, Bud Tinning, and Lon Warneke) to start every game of the season for the third-place Cubs, Henshaw (2-1) was nursed along in 21 appearances, often in mop-up situations, logging 38⅔ innings with a 4.19 ERA.

Henshaw spent the entire 1934 campaign with Los Angeles of the Double-A Pacific Coast League. Philip K. Wrigley, who had taken over the Cubs after the death of his baseball-obsessed father, William, in 1932, also owned the Angels. They played in Wrigley Field in South LA, which was designed by Zachary Taylor Davis, who had also designed Comiskey Park and Weeghman Park (renamed Wrigley Field in 1927). With the chance to pitch regularly, Henshaw posted a 16-4 record and a stellar 2.76 ERA in 196 innings, and was the hardest-to-hit hurler in the circuit (6.8 hits per nine innings) as the Angels steamrolled opposition en route to a 134-50 record and the league championship.

Henshaw’s chances to make the Cubs in 1935 seemed bleak considering the team’s offseason acquisition of durable southpaw Larry French, who had averaged 16 wins and 276 innings pitched over the last five campaigns with the Pittsburgh Pirates. But the Chicago native arrived in camp a week early and subsequently surprised everyone. Skipper Charlie Grimm considered his performance one of the “most heartening” at spring training.8 Chicago sportswriter Ed Burns gushed about Henshaw’s significant improvement since his rookie campaign and raved about his attitude; “he loves to pitch and is always trying to learn.”9 Despite those laudatory comments about Henshaw, the acerbic Burns derided the Cubs as “a sluggish ball club, a team with an inadequate pitching staff in addition to its lack of alertness.”10 As “Jolly Cholly’s” squad traveled in their Pullman coaches back to Chicago to kick off the season, Burns added, “It would be a gross inaccuracy to report that the pennant bee is buzzing on this train.”11 One of the most memorable surges and the longest winning streak in baseball history made Burns eat crow about 5½ months later.

Henshaw proved he was no spring training fluke by tossing an eight-hit shutout to beat the Pittsburgh Pirates on April 29 in his first start of the season. Sportswriter Edward F. Balinger of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette quipped that Henshaw “made the Pirates jump through a lot of hoops like trained seals.”12 Henshaw also got his first of seven career RBIs. [He was otherwise unaccomplished at the plate, batting .179 with 41 career hits.] Henshaw terrorized the left-handed-heavy Bucs all season long, making seven of his 18 starts against the club from the Smoky City, winning six of them and picking up another victory in relief. “[Henshaw] ought to get down on his knees and say a prayer of thankfulness that the Bucs are in the same league with him,” suggested Pittsburgh sportswriter Ralph Davis sarcastically.13 After defeating Pittsburgh at Wrigley Field on June 28, Henshaw was mobbed by teammates congratulating him for his no-hitter. Moments later a near riot erupted when word came down from the press box that Pirates reliever Mace Brown’s liner to short center field in the sixth inning had been ruled a double and not a two-base error. [At the time the scoreboard at Forbes Field did not show hits and errors]. According to both the Tribune and the Post-Gazette, Cubs center fielder Freddie Lindstrom had both hands on the ball, which grazed his glove, falling to the ground.14

After struggling to play .500 ball for the first half of the season, the Cubs got rolling in July, winning 26 of 34 games to get back into the pennant picture. On September 3 they were in third place, just 2½ games behind the New York Giants and trailing the St. Louis Cardinals by a half-game before commencing a record 21-game winning streak to capture their third pennant in seven seasons. Proving their critics wrong, the Cubs (100-54) were league’s highest-scoring team (847 runs) and paced the majors in team ERA (3.26), led by Lon Warneke (20-13), Bill Lee (20-6), and French (17-10). Henshaw (13-5) won his last seven decisions and posted a 3.28 ERA in 142⅔ innings.

Nominal favorites to capture its first title since 1908, Chicago lacked the star power of its opponents in the World Series, the Detroit Tigers, who boasted four future Hall of Famers, Mickey Cochrane, Charlie Gehringer, Hank Greenberg, and Goose Goslin. In a series most remembered for the Cubs’ vile bench jockeying and anti-Semitic remarks directed toward AL MVP Greenberg, the Cubs lost in six games. Henshaw made his only appearance in the Series in Game Two, relieving Charlie Root, who had given up four runs, including a two-run homer by Greenberg, without registering an out in the first inning. Henshaw hurled 3⅔ innings, surrendering three runs and walking five.

Henshaw once again assumed the role of spot starter and reliever for the Cubs in 1936. His spell over the Pirates ended in his season debut (14 hits and nine runs, five earned, in 8⅔ innings), in what emerged as a frustrating campaign for the hurler and his team. Henshaw tossed four complete-game victories over a five-start stretch (May 16-June 9), but won only two more times, including a 1-0 blanking of Philadelphia that proved to be his final of five big-league shutouts. “Henshaw fell off badly in effectiveness,” opined Burns in the Tribune.15 His ERA rose to 3.97 (about league average) in 129⅓ innings spread over 39 appearances. Widely expected to repeat as pennant winners, the Cubs held sole possession of first place on August 2, two games in front of New York. Thereafter the North Siders played uninspired ball (28-31) to finish in second place. Vowing radical changes, team owner Philip K. Wrigley shocked the baseball world by trading Warneke, winner of 98 games in the previous five seasons, to St. Louis days after the disappointing season ended. At baseball’s winter meetings in Montreal, Henshaw was shipped on December 5 along with backup shortstop Woody English to the Brooklyn Dodgers for shortstop Lonny Frey.

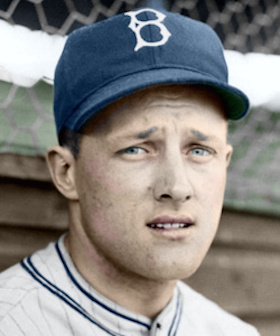

Throughout Henshaw’s career sportswriters had a field day with his height. Descriptors such as diminutive, half-pint, midget, tiny, wee, and mighty mite were ubiquitous. The 5-foot-8 Henshaw entered the league weighing 150 pounds at most, though he packed on another 15 by the time he retired. Brooklyn sportswriter Stan Lomax went so far as to suggest that Henshaw “looks much smaller than he really is,” citing his symmetrical build and the lack of broad, pitcher’s shoulders.16 References to the southpaw’s height were frequently tempered by praise of his baseball intellect. “[Henshaw is] a serious minded athlete and an avid student of the game,” opined Ed Burns of the Chicago Tribune in what might pass for a typical appraisal.17 “A big picture in a small frame,” waxed Brooklyn sportswriter James J. Murphy poetically, “Roy makes up what he lacks in size with the skill of a giant.”18

By all accounts, Henshaw was a likeable player and respected by his teammates. Few big-league ballplayers went to college at the time, a fact often stressed by sportswriters. Erudite and bookish, Henshaw had blue eyes and blond hair, with smooth facial features, and was not known as a carouser like some of his teammates. He was also fashionable, often wearing tailored double-breasted suits.19

Henshaw was also considered the best table-tennis player in baseball, and typically arrived at spring training armed with personal paddles and expensive celluloid balls. He once claimed that 30 minutes of ping pong was more physically exhausting than three hours of baseball practice. He supposedly learned the game from Coleman Clark, a former national champion and a classmate at the University of Chicago.20

Henshaw married Jeanette Walter, of German descent, on October 16, 1935, nine days after the Cubs lost the World Series. The losers’ share of the World Series enriched the newlyweds by $4,554.21 An avid Dodgers fan who grew up just a block from Ebbets Field, Jeannette once joked that “I possibly had joined the fans hooting at him” when the Cubs were playing in Brooklyn.22 By one account the couple met at a Jersey Shore resort through mutual baseball acquaintances.

In 1937 Henshaw unexpectedly earned a spot in Brooklyn’s starting rotation for new manager Burleigh Grimes, who had replaced Casey Stengel. (The club’s only left-hander from the previous season, Ed Brandt, had been traded to Pittsburgh in the offseason.) Essentially a two-trick pony, Henshaw relied on heaters and hooks. He tossed a side-arm curve to left-handed hitters, and typically an overhand version that he had learned from Lon Warneke to righties. “I started to improve my curve ball late [in 1936] and worked on it again this spring,” said Henshaw. “I know it is a lot better than the hook I had a year ago.”23 Henshaw whiffed a career-high nine in a no-decision against Philadelphia in his season debut, but was relegated to his customary role of swingman after two subsequent rough outings. Twice against the cellar-dwelling Cincinnati Reds, Henshaw pulled lightning out of a bottle, raising his strikeout record by whiffing 10 batters in two complete-game victories, one of which was a 10-inning affair. In an otherwise forgettable season for the sixth-place Dodgers, Henshaw won only five of 17 decisions and posted the third highest ERA in the NL (5.07); he struck out 5.6 batters per nine innings, fourth best in the circuit, and set personal highs in appearances (42) and innings (156⅓). Days after the conclusion of the season, Henshaw was shipped along with utilityman Jim Bucher, outfielder Johnny Cooney, and third baseman Joe Stripp to the St. Louis Cardinals for shortstop Leo Durocher.

Henshaw’s two-year stint in the Cardinals organization was filled with controversy and disappointment. After just one relief appearance he was released to the club’s affiliate in the International League, the Rochester Red Wings, on May 7.24 Henshaw refused to report. He and pitcher Si Johnson, who had also been released, appealed to Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, claiming that they had not been given “a fair shake” to make the team.25 Landis had receptive ears. For years he had voiced his objections to the Cardinals’ expanding farm system, the brainchild of GM Branch Rickey. In March Landis had granted 74 players from the Cardinals “chain gang” free-agent status, arguing that St. Louis had illegally controlled multiple teams in the minor leagues and violated rules by selling players among those teams.26 Sam Breadon, owner of the Cardinals, was incensed by Henshaw and Johnson’s action and questioned whether Landis had the authority to adjudicate the case, adding, “Any time we assign a player anywhere, he rushes to Judge Landis with a complaint,”27 Ultimately Landis ruled that both players must be returned to the Cardinals, causing a stir, especially among owners. Nationally syndicated sportswriter Dick Farrington noted that it was the first time the commissioner set himself up as the judge of a player’s capabilities.28 Henshaw returned to the club in late May and tossed three complete-game victories in June, but won only two more games all season. The once mighty Cardinals slipped to sixth place with just 71 wins, their lowest total since 1924. Itching to get rid of Henshaw, Rickey released the hurler to Rochester in exchange for pitcher Ken Raffensberger in December.29

Dissatisfied with his demotion, Henshaw struggled with Rochester, posting an abysmal 5.41 ERA and wining just six times. At baseball’s winter meetings in Cincinnati he was traded to Jersey City, the New York Giants’ affiliate in the Double-A International League, for Lincoln Blakely.30 Just 28 years old but lacking the physical stature to be a durable full-time starter, Henshaw turned in two strong seasons with Jersey City as a swingman. In 1941 he went 13-9, finishing with the league’s second best ERA (2.34), and was the third hardest pitcher to hit (7.3 hits per nine innings).

Henshaw’s season for the International League’s runners-up bought him another shot on the big stage. On the recommendation of Steve O’Neill, manager of the Buffalo Bisons, against whom Henshaw had tossed a one-hitter, the Detroit Tigers selected Henshaw in the Rule 5 draft on September 30, 1941.31 Henshaw, whom catcher and roommate Paul Richards nicknamed “Firefly” for obvious reasons, was used sparingly and primarily in long relief in mop-up situations in his two seasons with Detroit.32

During World War II, Henshaw was classified 3-A and given a draft deferment because of his wife and young son. He worked as a salvage inspector at the N.A. Woodworth airplane parts manufacturing plant in Ferndale, a suburb of Detroit, in 1942 and 1943.33 The following year, Henshaw went on the voluntarily retired list to work at a radio station on war-related projects in Chicago.34 He returned to the Tigers in early October, and made his last seven big-league appearances. His career in Organized Baseball came to an official end the following spring when he refused to report to Buffalo, to whom the Tigers had traded him and Bubba Floyd in exchange for outfielder Ed Mierkowicz and catcher Milt Welch.35 In parts of eight major-league seasons, Henshaw posted a 33-40 record with a 4.16 ERA in 742⅓ innings. He started in 71 of his 216 appearances.

According to his contemporaries, Henshaw had one of the best pickoff moves of the 1930s and early ’40s .“He had the best motion to first I ever saw,” said catcher Buddy Rosar, a five-time All-Star catcher. “It was a half-balk. He used to throw his leg in the direction of first base, and if the runner took liberty, he was picked off.”36

The luxury of an affluent family afforded Henshaw the opportunity to pursue baseball when many retired players were forced into a 9-to-5 job. He spent the summer of 1945 in Michigan, where his folks had a summer residence on Lake Michigan, hurling for Michigan City, Indiana, an amateur team, and grabbed headlines as a strikeout artist.37 The following year, Henshaw briefly revived his professional career with Vera Cruz in the independent Mexican League before returning to Michigan, where he led a semipro club from St. Joseph to the National Baseball Congress championship in Wichita, Kansas. Henshaw won four games in the tournament and was named the best pitcher.38

Henshaw eventually returned to Chicago, where he was employed as a salesman for Hankins Container in Clearing, a section of Chicago near Midway Airport. He died at the age of 81 on June 8, 1993, at Memorial Hospital in LaGrange, and was buried at the Mount Hope Cemetery in Chicago.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Henshaw’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, Bill Lee’s The Baseball Necrology, the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com, The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record, and Ancestry.com.

Notes

1 “An Ambidextrous Case,” Detroit Free Press, June 5, 1932: 37.

2 United Press, “Chicago University Baseball Team Leaves on Playing Tour of Japan,” Logansport (Indiana) Pharos-Tribune, August 4, 1930: 6.

3 “Chicago Hurler Making College Ball History,” Suburban Economist, May 22, 1931: 7; “Star Maroon Hurler,” Montana Butte Standard, June 14, 1931: 20.

4 Associated Press, “Takes Sponge Back, Becomes Diamond Star,” Montana Butte Standard, June 14, 1931: 16.

5 Tommy Holmes, “Chicago Cubs Are to Defend on Youngsters,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 10, 1933: 18.

6 United Press, “Chicago Cubs Stand Pat on 1932 Baseball Club,” Morning News (Danville, Michigan), November 30, 1932: 8.

7 Newspaper Enterprise Association, “Star College Southpaw May Aid Cubs’ Hurling,” Dunkirk (New York) Evening News, March 13, 1933: 13.

8 The Sporting News, April 11, 1935: 5

9 The Sporting News, March 21, 1935: 3.

10 Ed Burns, “Our Cubs Dream, of Many Things, But Not of Flag,” Chicago Tribune, April 4, 1935: 20.

11 Ibid.

12 Edward F. Balinger, “Scoring Chances Muffed by Bucs; Henshaw Puzzle,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 1, 1935: 18.

13 The Sporting News, August 15, 1935: 13.

14 Edward Burns, “Fluke Double Robs Henshaw of No Hit Game,” Chicago Tribune, June 29, 1935: 17; Edward F. Balinger, “Brown’s Disputed Drive Only Blow Off Cubs Lefty,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 29, 1935: 14.

15 Edward Burns, “Cubs Obtain Frey for English, Henshaw,” Chicago Tribune, December 5, 1936: 29.

16 Stan Lomax, “Henshaw Gained Big League Berth Direct From Campus,” undated article from 1937 from player’s Hall of Fame file.

17 Ed Burns, “Fred Lindstrom Signs Up to Play Third For Cubs,” Chicago Tribune, January 11, 1935: 25.

18 James J. Murphy, “Henshaw and Hankin, David, Goliath Sign With Dodgers,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 20, 1937: 8.

19 “Roy Among Game’s Quiet and Educated,” Detroit Free Press, May 10, 1942: 10.

20 Dale Stafford, “Henshaw Shines at Table Tennis,” Detroit Free Press, March 23, 1943: 14.

21 Irving Vaughn, “Cubs Go Home; Grimm Hints He Plans on Trades,” Chicago Tribune, October 9, 1935: 25.

22 “My Hubby Plays Baseball,” March 23, 1937. Unattributed article from player’s Hall of Fame file.

23 Edward T. Murphy, “Dodgers Think Henshaw Good,” 1937. Unattributed article from player’s Hall of Fame file.

24 J. Roy Stockton, “Cardinals Release Henshaw and Bush; Warneke Due Today,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 8, 1938: 9.

25 The Sporting News, May 26, 1938: 1.

26 Kevin Stiner, “Commissioner Landis Frees 74 Cardinals Farmhands,” National Baseball Hall of Fame, baseballhall.org/discover/inside-pitch/commissioner-landis-frees-74-cardinals-farmhands.

27 Associated Press, “Frisch Confers With Landis on Player Release,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 16, 1938: 11.

28 The Sporting News, May 26, 1938: 1.

29 “Cardinals Buy Shortstop From Rochester,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 17, 1938: 7.

30 Associated Press, “Minors to Guard ‘Double’ Territory,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 6, 1939: 14.

31 “Roy Among Game’s Quiet and Educated,” Detroit Free Press.

32 Charles P. Ward, “Ward to the Wise,” Detroit Free Press, April 6, 1944: 12.

33 Joe Block, “Nation’s Diamond Heroes Show Unusual Winter Jobs for a Place in War Effort,” Detroit Free Press, December 20, 1942: 23.

34 “Henshaw Unlikely to Play this Year,” Detroit Free Press, March 10, 1944: 14.

35 The Sporting News, March 15, 1945: 17.

36 The Sporting News, March 3, 1947: 2, 3

37 “Roy Henshaw Coming Here With Michigan City Cubs,” News-Palladium (Benton Harbor, Michigan), July 10, 1945: 5.

38 The Sporting News, September 18, 1946: 3.

Full Name

Roy Kniklebine Henshaw

Born

July 29, 1911 at Chicago, IL (USA)

Died

June 8, 1993 at La Grange, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.