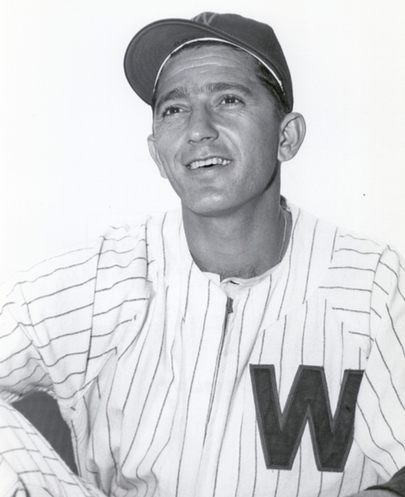

Julio Moreno

“Jiquí” Moreno was not big (5’8” and 165 pounds) — but he threw hard. How hard is jiquí wood? In Cuba, Moreno’s native land, linemen could not sink their spurs into telephone poles made from this tree — they had to use ladders. Brick stair steps wore down, yet their jiquí binding was simply polished. That’s how tough this pitcher was in his heyday at home.

“Jiquí” Moreno was not big (5’8” and 165 pounds) — but he threw hard. How hard is jiquí wood? In Cuba, Moreno’s native land, linemen could not sink their spurs into telephone poles made from this tree — they had to use ladders. Brick stair steps wore down, yet their jiquí binding was simply polished. That’s how tough this pitcher was in his heyday at home.

“The Cuban Bob Feller” had a spectacular record in high-level amateur ball in the early 1940s. After turning pro, the righty remained a major year-round drawing card in Havana. He was one of many Cubans whom Joe Cambria signed for the Washington Senators. Journalist Fausto Miranda — older brother of Willy Miranda, a friend and teammate in Washington — called him “The Meteor of Güines.”1

Moreno had lost that fastball by the time he reached the majors in 1950 — yet he was durable. It is said that jiquí posts driven into the ground by the conquistadores in 1514 were still sound over four centuries later. Relying on craft as he battled through arm problems, Julio wound up pitching both summer and winter ball for close to 30 years. His last big-league game came in 1953, but his career extended well into the ’60s, mainly in Cuba, Mexico, and Nicaragua. He was also a manager in the latter two nations. Jiquí returned to the majors as a tireless batting-practice pitcher for two seasons with the Detroit Tigers — including the 1968 champion team. For much of his later life, he devoted his energies to coaching Cuban-American children in his adopted home, Miami.

Julio Moreno González was born on January 28, 1921, in the country town of Güines.2 Although this place is just 30 miles southeast of Havana, it is entirely different in character. In 1919, the Home Mission Monthly described the locale. “Güines, Cuba, is a city of some 13,000 inhabitants. Situated in a fertile valley, it is watered by a stream used during the dry season for irrigation. It is noted for its fine vegetables. . .but the chief crop is sugar cane.”3

Julio was the youngest of six children born to José Moreno, who worked in the local fields, and Juana González. He had one brother named José Manuel and four sisters named Carmen, Teresa, María, and Margo. Julio’s first sport at home was soccer, but he later said, “I was very small and very skinny for football.”4 So he turned to Cuba’s true national pastime.

The quality of Cuban amateur baseball in Moreno’s day — even though white-only social clubs dominated the scene — bears emphasis. Peter Bjarkman, an expert in the game’s history on the island, described it as “a thriving tradition that grew up alongside Havana’s pro league and that, for much of the first half of the twentieth century, actually outstripped the pro game in island-wide popularity and fan stature.”5 The respectable record of Cuban all-star teams against major-leaguers in that era also attests to the level of competition. After the Boston Red Sox lost such a game in 1941, manager Joe Cronin reportedly said, “They may be amateurs, but many are better than our players.”

Author Roberto González Echevarría, who has also written extensively on Cuban ball, further set the scene for Moreno’s early career.

“A significant development in the thirties and forties was the emergence of players, mostly pitchers, from the provinces. . .white guajiros — country bumpkins.” He added that “the rural aristocracy of the Amateur League. . .fed on the nationalism of the period.” The foremost of these “revered amateurs and later professionals” was Conrado Marrero, El Guajiro del Laberinto, but Moreno was a distinguished runner-up. The pair met in some renowned duels as amateurs. They would later pitch together in the U.S. with the Senators, as did Sandalio “Potrerillo” Consuegra (known as “Sandy” in the U.S.) and Rogelio “Limonar” Martínez. In their amateur days, all four “often appeared in magazines, sometimes even on the covers.”6 One such picture of Moreno shows him with the pencil mustache he then sported, as did many Hollywood stars of the time.

According to a capsule biography on the Círculo Güinero de Los Ángeles website, young Moreno started to play baseball in Güines with a team known as Estrellas de Pancho (Pancho’s Stars). He started to attract wider attention in 1938. In his obituary of Moreno, Fausto Miranda told the story of how he first saw the pitcher. Julio, then just 17, was facing a visiting team called Películas Cubanas (Cuban Movies), organized by two famous comedians and baseball enthusiasts named Alberto Garrido and Federico Piñero. The smiling youth was very fast. . .and very wild. After watching a batter hit the deck, Garrido said, “Careful, that skinny boy’s going to kill someone here today!” Miranda said, “We all came back to Havana talking about the terrifying speed of this kid who barely weighed 135 pounds.” 7

Starting in 1940, Moreno joined Círculo de Artesanos, a team representing San Antonio de los Baños in the Cuban amateur league. Early on, like many young flamethrowers, he continued to struggle with control — but he developed rapidly over the course of his five years with this club. In 2009, Conrado Marrero (then 98 years old) remembered “a young and super-skinny boy, who was practically unknown to us. Already by his second season, though, he was a more experienced pitcher.”

Jiquí first appeared internationally after the Amateur World Series of 1940. Following the tournament, which took place in Havana, the Cuban team was invited to Caracas to face a Venezuelan squad in the Simón Bolívar Cup. Star lefty Pedro “Natilla” Jiménez couldn’t get permission to go from his employer, the Central Hershey mill. Andrés Castro from San Antonio de los Baños said, “If Natilla can’t go, they should bring this youngster — they shouldn’t hesitate, because he’s going to be the best of all.”8

Moreno went on a crash program ahead of the trip. He put on some weight, developed endurance through physical training, and got some much-needed dental work. The effort paid off, as young Julio helped Cuba win the trophy and established himself as a first-rank pitcher.9

Once he matured fully, El Jiquí became truly dazzling. “The announcement that Moreno was pitching on Sunday afternoon made fans across the nation come to attention.”10 (Amateur league games took place just once a week.) His records from that era are incomplete, but the progression is notable.

In 1941, Moreno won 10 and lost 6. He also pitched for Cuba in the Amateur World Series for the first time, going 1-1 with a 1.29 ERA.

In 1942, he made a quantum leap — 20-5 with a 1.76 ERA and 213 strikeouts. In the Amateur World Series, he won three games and lost none with an ERA of 1.36 as Cuba beat Venezuela to avenge its loss the previous year. He struck out 31 in 33 innings.

In 1943, which at least one other expert, César López, viewed as the best-quality season for the Cuban amateur league, Jiquí was 20-6 with 276 Ks. In the Amateur World Series, held in Havana for the third straight year, he added three more victories with a 0.70 ERA for the gold medalists. At that time, wrote Roberto González Echevarría, he “was at the peak of his invincibility and reputation as a strikeout artist.” He did lose once to Mexico that Series, in a 14-inning, 2-1 epic that González Echevarría called “one of the true masterpieces of Latin American ball.”11

In 1944, Moreno was 26-3, 1.19, striking out 319 men — 13.44 per nine innings. He was 2-2 in his final Amateur World Series (from which Cuba withdrew in protest). His noteworthy single-game feats that year included a no-hitter against Atlético de Santiago de las Vegas on March 19 and a record 21 strikeouts against Vedado Tennis Club on April 9. 12

“I was born with the gift of velocity,” Julio told journalist Luis Pérez López in March 1985. “That’s something that can’t be learned or practiced. It is a gift of nature.”13

Adolfo “Dolf” Luque wanted to sign Moreno for the New York Giants.14 Luque was then a coach with the Giants, who already had another Cuban pitcher, Adrián Zabala, in their chain. According to a May 1944 report in The Sporting News, “Julio is said to have declined offers from the Giants and Senators in order to continue pitching for Círculo de Artesanos. ‘The Great Jiquí’. . .is an average Cuban rural boy, standing about five feet seven inches and weighing 150 pounds, who does not give the impression of having the blinding speed he uses.”15

That December, Cuban journalist and baseball official Jess Losada called Julio the island’s best baseball prospect. “You can imagine how good Moreno looks from the fact that Joe Cambria. . .has offered him a bonus of $300 to sign. Moreno will not go with Washington. He wants to remain in Cuba until the war is over.” Losada also expressed his ongoing unhappiness with Cambria’s talent raids.16

More important, though, was Julio’s loyalty to Artesanos — there was a true amateur ideal at work. Once his team won the national amateur championship, with a sense of mission accomplished, he finally decided to turn pro.17 He did not go straight to the Cuban winter league, though, waiting until the next year instead.

Julio found personal happiness in San Antonio de los Baños, too, as he met his wife-to-be, Blanca Rodríguez. Conrado Marrero recalled her as “a very proper and educated woman.” Julio and Blanca got married on February 19, 1945.18 They had one daughter, Diana. Moreno said, “After my family, baseball has been the biggest thing in my life.”19

In the summer of 1945, the newlywed went to Mexico, and the Veracruz Azules, owned by magnate Jorge Pasquel. Many observers said he went where the money was. Julio himself said, though, that his decision was more about becoming a better pitcher and being in a place where he knew the people and they spoke his language — in a word, the atmosphere.20 Julio won 15 games for the Blues that summer, but he wouldn’t return to Mexico for more than a decade.

Moreno made his Cuban winter debut in the 1945-46 season with Marianao. After being such a big winner in amateur ball and having a good year in Mexico, this season was a shocker — El Jiquí won only one game and lost a league-high 10. His ERA is not available, so it is tough to tell whether he was a hard-luck loser. In February 1946, however, he was part of a Cuban All-Star squad that faced the league’s U.S. All-Stars in Havana. Adrián Zabala and Moreno combined on a one-hitter (Dick Sisler got the only hit). That year, there was a short-lived Cuban summer league. Julio pitched for the Regla team, also managing for part of the season.

The winter of 1946-47 saw Moreno pitching for the Havana Reds in La Liga de la Federación. This league sprang up after entrepreneurs Bobby Maduro and Miguelito Suárez built Havana’s new Gran Stadium. In response, Julio Blanco Herrera — the proprietor of the Cuban Winter League’s old ballpark, La Tropical — started a rival circuit. The Federation was in good standing with Organized Baseball, whereas the Cuban Winter League was using “outlaw” players who had jumped to Mexico in 1946. Attendance was poor and losses were heavy, however; the Federation folded as of year-end 1946.21 Moreno (4-3 with the Reds) did not join a Winter League team for the remainder of the season.

Joe Cambria finally did get Jiquí for the Senators in 1947. For the next three-plus summers, he pitched for the Havana Cubans, a Washington farm team in the Florida International League. Moreno’s first year with the Cubans, as the number-two starter behind staff ace Conrado Marrero, was superb. He won 16 and lost just 4 in the regular season and added three more wins in the playoffs as the team won the league title. In October 1947, the Havana Cubans then faced the New York Cubans of the Negro Leagues in a five-game exhibition series at Gran Stadium. Julio lost the second game 3-0 to Dave “Impo” Barnhill.22

Jiquí got into only eight games with the Cubans in 1948. One suspects he was injured; after early April his name did not appear in the U.S. papers. In addition, he pitched just three innings in three games for Cienfuegos that winter. He was good, not great, for Havana in 1949 (12-6, 3.40), missing several weeks in the early going that year due to illness.23

At some point during their time together with the Cubans, Conrado Marrero taught his out pitch — the slider — to Moreno. Marrero recalled in 2009 that even though Jiquí had a good fastball, it had lost some of the zip that made him an amateur star. The veteran added, “He was always a very good pitcher, with good control and an excellent overhand curve.”

Moreno joined the Havana Rojos starting in the 1949-50 winter season. The Reds won three league championships in a row starting in 1950-51, so Julio got to play in the second through fourth Caribbean Series (1951, 1952, and 1953). Cuba was the winner in 1952. Moreno pitched in four games overall, neither getting a decision nor allowing an earned run.

Jiquí was in fine form during the summer of 1950: 16-4 with a league-leading 1.47 ERA. The Senators first bought him from Havana in late July, sending down Limonar Martínez (who pitched just twice in the majors). The Associated Press noted that Moreno had a split finger and could not pitch “for a few days.”24 He stayed in Havana until he was called up for certain in mid-August. He was to report “as soon as Havana can find a suitable replacement.”25

Julio did not make his debut until September 8 — it was a 10-4 win over the Philadelphia Athletics at Griffith Stadium. He took a shutout into the eighth inning, and manager Bucky Harris let him go the rest of the way for a complete game. The 29-year-old rookie started twice more and relieved once during the tail end of the season.

Moreno remained with the Senators throughout 1951 as a swingman, starting 18 times in 31 games. Three of his five wins (he lost 11) came against Cleveland. A photo in the June 11 issue of Life magazine shows Jiquí — looking sporty in a light summer suit and an open-collared shirt — hanging out at Alamo’s Hollywood Barbershop in Washington with Marrero, Fermín “Mike” Guerra, and Willy Miranda.

Julio would also stick with the Nats in 1952, making a career-high 22 starts and completing seven as he went 9-9. Perhaps his most impressive performance as a big-leaguer came that April 16 at Griffith Stadium against the Boston Red Sox. He lost a 3-1 lead in the ninth inning on two unearned runs, but hung on to get an 11-inning complete-game win with nine strikeouts. Yet Moreno said that his greatest thrill came when he beat his childhood favorite, the New York Yankees.26 That August 7, again at Griffith Stadium, he scattered 12 hits and went all the way to win 4-2.

In 1953, though, Jiquí started just twice in 12 sporadic appearances. His last game in the majors came that June 26. Shortly thereafter, the Senators swapped a shortstop, a catcher, and a pitcher with their Chattanooga farm club in the Southern League (Double A). Jerry Lane (2-6 lifetime in the big leagues) was the pitcher who took Jiquí’s place.

After spending the rest of the ’53 season with the Lookouts (4-6, 5.72), Moreno returned to Havana, which had moved up to the Triple-A International League, for the summers of 1954 and 1955. Despite the local hero’s P.R. value, they were two more undistinguished seasons spent mainly in the bullpen; the logical hunch is that Jiquí was battling more arm problems.

In April 1956, the Sugar Kings sold Moreno to Yucatán in the Mexican League. The manager of the Leones was old friend Adolfo Luque, who had also managed him in Havana for the previous two winters. Julio’s 6-18 record suffered from lack of batting support, as his ERA was 3.00. For example, fellow Cuban pitcher Vicente López — a future business colleague — remembered beating Jiquí 2-1 that August.27 The 10-inning duel gave the Mexico City Reds their first league pennant.

Although Jiquí would pitch 10 more summers in Mexico, his winter career would start to follow a winding path. He played in Cuba for Cienfuegos again in 1956-57, though there was also a report in mid-season that he had signed with the Indios club in Colombia (it is not certain whether he ever played there).

Yucatán won the Mexican League championship in 1957, despite an off-year from Moreno (5-7, 4.59). In 1985, he said that his ups and downs in pro ball were the result of bone spurs in his right elbow. “My worst moment in baseball was in 1957 when Cienfuegos left me out and no one else was interested in me. But with medical attention, vitamins, exercise, and an extraordinary effort on my part, I recovered and became Jiquí Moreno again.”28

He got the opportunity to bounce back in Nicaragua. That nation’s first professional league had begun play in 1956, and 1957-58 was its first season affiliated with the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues (i.e., Organized Baseball). Julio joined the GMC Truckers, so called because they represented the tri-cities area of Granada-Masaya-Carazo. The team was also known as “Oriental,” meaning East Nicaragua, even though that is an entirely different region. Moreno was then traded to Cinco Estrellas. Overall, he was 4-1, 3.27 in 80 innings pitched.

Back in Mexico in 1958, the Nuevo Laredo Tecolotes picked up Moreno after Yucatán released him. Jiquí went 13-8 and won the first of his two Mexican ERA titles at 2.70, helping the Owls to become league champions. He followed up with 18 wins in 1959, his highest one-season total in Mexico.

After one more winter with Cinco Estrellas (4-1, 2.99 with 10 starts in 22 games), Moreno went to León in 1959-60. It was his finest season in Nicaragua. Starting 15 out of his 24 games, he was 10-6 with a league-leading 1.91 ERA, thanks to three shutouts. He also led the league in innings (146) and complete games (11). In addition, Jiquí struck out nearly a batter per inning — even though, as longtime local observer Carlos Mena remembered in 2010, he had no speed by the time he got to Nicaragua. Mena called Moreno “a quiet, nice gentleman who was very crafty. He was a very intelligent pitcher, who depended on a great curve and considerable knowledge, the same thing he used to be a successful manager.”

Indeed, Julio took over for fellow Cuban Wilfredo Calvino as manager in the second half of the season. He led the Melenudos (the Long-Haired Ones, referring to a lion’s mane) to the Nicaraguan championship over Cinco Estrellas, managed by Johnny Pesky. He threw another shutout in the opener of the playoffs and then came on for saves in Games 2 and 3. Alas, poor attendance meant that the winner’s share was a paltry $24 per man.29

The Nuevo Laredo franchise was transferred to Puebla for the 1960 season, which was Moreno’s worst in Mexico (6-13, 5.11). He also managed the Pericos for the second half of that summer after Jesús “Chanquilón” Díaz was fired.30 From 1960 to 1963, one of Jiquí’s big-league contemporaries joined him on the Parrots roster: former Brooklyn Dodger Dan Bankhead, who had been knocking around Mexico since 1953.

Economic problems caused the Nicaraguan League to suspend play for the winter of 1960-61. Jiquí returned to Havana for the Cuban professional league’s last campaign, in which only native players took part. In 75 innings as a reliever, his 2.03 ERA was the league’s best (although Pedro Ramos posted a 2.04 mark as a starter) and he had a 3-5 record. This brought Moreno’s lifetime record in Cuban winter play to 44-55, 3.65 in 243 games. From 1962 on, however, he remained in exile from his native land.

Julio did not return as Puebla’s manager in 1961, but he won his second league ERA crown at 3.02 to go with his 13-4 record. In the winter of 1961-62, Nicaragua joined forces with Panama to form a league. Moreno pitched for one of the Panamanian entries, the Marlboro Smokers. It was a split season; the first half was played in Managua and the second in Panama City. Marlboro won the second half and then beat first-half leader Bóer in the playoffs, which were held in Managua because attendance in Panama had been poor. Jiquí, who was 4-5, 2.61 in the regular season, staved off elimination with a 12-0 four-hitter in Game Six.31

The Smokers then participated in the second Inter-American Series, which had replaced the Caribbean Series after the withdrawal of Cuba. They finished just 1-8 in the triple round robin. Jiquí lost to Bob Gibson, who was hurling for the tournament winners, the Santurce Crabbers — but he got the Panama team’s lone victory over Mayagüez and Joel Horlen.32

The summer of 1962 featured a brief return to the United States. Bobby Maduro, Jiquí’s employer with the Havana Sugar Kings, had come to own the Jacksonville Suns, then a triple-A farm club for the Cleveland Indians. Maduro was also his own general manager. The Suns purchased the veteran from Puebla in early August, and they went on to win the International League pennant. With the playoff berth already sewn up, Moreno got his only win with a complete game on the last day of the season. However, he was left off the postseason roster.

That winter, Nicaragua was back on its own, and Moreno returned to León, once again as pitcher-manager.33 His record was 8-10, 2.20; he led the league in games with 23 (15 starts) and complete games with 10. He also reinforced the Bóer team that represented Nicaragua and finished second in the 1963 Inter-American Series.

Puebla won the Mexican League championship in 1963, which was one of Jiquí’s best seasons there (15-5, 3.02). Late in the season, he suffered an attack of Bell’s palsy (facial paralysis), but he returned to win the title-clinching game.34 35

Moreno continued with León as a playing manager in 1963-64. He lost his first five decisions but finished 10-7 and led the league in wins.36 Julio remained in the same dual capacity the following winter, and though he cut back on his own mound duties, he was still generally effective.

Starting in 1965, Jiquí — by then well into his forties — shifted to the bullpen for Puebla. His name surfaced only once in The Sporting News that winter; it does not appear that he got beyond the negotiating stage with Oriental, which by then was largely representing Granada. Moreno quit summer ball after the 1966 season. His lifetime record in Mexico was 124-99 with a 3.85 ERA in 360 games.

In 1966-67 — the last season of the first professional era in Nicaragua — Jiquí returned to Cinco Estrellas as manager. Again he replaced Wilfredo Calvino when Calvino took an offer to manage San Juan in Puerto Rico.37 Coaching under Julio was local hero Stanley Cayasso, a longtime star for Cinco Estrellas. The Tigers finished second in both halves of the season but made the playoffs under a points-based system. They then won the championship, which ended just before a brief but bloody revolt on January 22-23, 1967. American players went home for their safety. Richie Scheinblum, who won the batting title for Cinco Estrellas that year, said, “We heard small arms fire and saw members of the mob carrying bodies away from the scene.”38

Moreno was still listed as a pitcher on the active roster that winter. He started one game and pitched an inning, allowing four earned runs, though he avoided the loss. It was his last turn on the mound as an active pro.

In 1968, Preston Gómez (then on the coaching staff of the Los Angeles Dodgers) gave his friend Moreno a hand. The Tigers needed a batting practice pitcher, and Jiquí was just the man for the job. That April, The Sporting News wrote, “Julio Moreno is a wonder as the new Detroit batting practice pitcher. At the age of 46 [actually 47], he can pitch 30 minutes every day.”39 The same beat columnist, Watson Spoelstra, observed in late August that Moreno “has amazing stamina. . .‘He’s getting stronger instead of weaker,’ said manager [Mayo] Smith.”40 When Detroit defeated the St. Louis Cardinals in the World Series that October, the team voted him a full Series share, $10,936.66.41 “Moreno did a great job all summer,” said Mayo. “We’re glad we got him.”42

Jiquí pitched BP again with the Tigers in 1969, but he then returned to Miami. In 1970, his friend Vicente López started a baseball academy called Los Cubanos Libres. In 2002, Miami journalist Gaspar González — who played at the academy in the late ’70s — wrote a feature on López. “He operated with the help of other former Cuban ballplayers, among them Moreno, Sandalio Consuegra, and Ray Blanco. The business was an instant success. Cuban exile parents who had grown up marveling at the feats of López, Moreno, and the academy’s other coaches eagerly signed up their children, hoping the old pros might make big-leaguers out of them. ‘We had 200 kids,’ exclaims López, thinking back to the academy’s early days. ‘Every team would play a doubleheader.’ One of those kids was Rafael Palmeiro.”43

In response to the González article, a man named José M. Blanco sent in a letter fondly reminiscing. “I also played for the Oakland team, coached by Julio ‘Jiquí’ Moreno, who would drive as many as five kids in his green sedan to the games on Saturday mornings. . .Vicente as well as Julio pitched batting practice, making sure every player got to hit. Vicente and Julio cared about every one of us — at least that’s how they made me feel. I am very grateful to Vicente López and Julio Moreno for giving kids like me the chance to play organized baseball.”44

In addition to his work with the children, Moreno also worked in the administrative offices of New England Oyster House, a Miami-area seafood restaurant chain. Later he was employed in the delivery department of Regal Wood, a manufacturer of kitchen cabinets.45 Julio’s main hobbies were automobiles and movies.

Jiquí Moreno was diagnosed with cancer in 1985. There’s reason to believe it was lung cancer. Puebla teammate Ronnie Camacho, speaking to Mexican baseball historian Jesús Alberto Rubio, remembered “[Moreno’s] inseparable cigarette in his lips.”

The highly popular figure could not make it to the Cuban old-timers’ game held at Miami Stadium that December, as he was recovering from an operation. According to Vicente López, “The surgeons just closed him back up. They couldn’t do anything for him.”46

Conrado Marrero had the opportunity to visit Miami around this time, and he went to see Jiquí. Moreno told his old friend that he made himself a true pitcher at Marrero’s side. Marrero was surprised by this gracious remark; in his own modest view, it was true that he had shown Julio grip and some other technical things, but he did not realize there was deeper significance.

Moreno passed away on January 2, 1987. His wife of nearly 42 years, Blanca, said he resisted until the last moment. “He never lost his spirit, and until the end he was conscious of what was happening.”47 Also surviving him were Diana, her husband, and their two children. His resting place is Miami’s Woodlawn Park South Cemetery.

The Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame inducted Moreno in 1976. During the 1980s, Fausto Miranda wrote a series of nostalgic columns for Miami’s El Nuevo Herald looking back on the pre-Castro age of Cuban ball. Many included Jiquí’s exploits. The retrospectives all began with the phrase, “Usted es viejo, pero viejo de verdad, si. . .” — which means, “You are old, but truly old, if. . .”

Yet even a quarter-century later, in 2010, another living link to the romantic Cuban amateur era could say — from personal experience — what it was like to catch Jiquí Moreno at his peak. That man, Andrés Fleitas (who died in 2011), was MVP of the 1942 Amateur World Series.

At age 92 in early 2010, Fleitas (like Marrero) displayed an extraordinary memory. “A tremendous pitcher,” he said without hesitation. “His fastball was 92, 93, 94 miles an hour, he had a great curveball, but above all good control. In a word: formidable. He was also a good teammate and great friend.”

An updated version of this biography appeared in “Cuban Baseball Legends: Baseball’s Alternative Universe” (SABR, 2016), edited by Peter C. Bjarkman and Bill Nowlin.

Acknowledgments

Grateful acknowledgment to Andrés Fleitas (telephone interview, January 31, 2010) and Diana Moreno Camacho (telephone interview, January 31, 2010). Continued thanks to Rogelio Marrero for obtaining Conrado Marrero’s input and to Tito Rondón for his additional research on Moreno’s career in Nicaragua.

Sources

About the jiquí tree:

Terry, Thomas Philip. Terry’s Guide to Cuba. Boston, Massachusetts, Houghton Mifflin Co.: 1926.

Standard Guide to Cuba. New York, NY: Foster & Reynolds, 1906: 150.

Figueredo, Jorge S., Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Press, 2003.

Figueredo, Jorge S., Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Press, 2003.

Treto Cisneros, Pedro, Editor, Enciclopedia del Béisbol Mexicano. Mexico City, Mexico: Revistas Deportivas, S.A. de C.V., 1998.

www.circuloguinero.org

www.retrosheet.org

www.cubanball.com

Photo Credit

The Topps Company. The 1953 Bowman card that is billed as Sandy Consuegra’s actually pictures Moreno. These men did resemble each other a good deal.

Notes

1 Miranda, Fausto. “Usted es viejo, pero viejo de verdad, si. . .” El Nuevo Herald, November 30, 1984. Sports-14. Even Miranda, however, could not say exactly who baptized Julio “Jiquí.” One distinct possibility is Cuban broadcaster Manolo de la Reguera, who bestowed many nicknames on players.

2 Note that the ü character in Spanish is pronounced like a ‘w’.

3 McKinney, E. Grace. “A Center of Christian Influence.” Home Mission Monthly, June 1919: 186.

4 Pérez López, Luis. “¡Ahí Viene la Bola del Jiquí Moreno!” El Nuevo Herald, March 30, 1985: 9.

5 Bjarkman, Peter C. Diamonds Around the Globe: The Encyclopedia of International Baseball. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2005: 6.

6 González Echevarría, Roberto. The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999: 220.

7 Miranda, Fausto. “Julio, El Hombre y Sus Pasiones.” El Nuevo Herald (Miami, Florida), January 5, 1987. Sports-8.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Pérez López, op. cit.

11 González Echevarría, op. cit.: 247.

12 Ibid.: 244, 248. Rogelio Marrero also provided some numbers from Cuban sources.

13 Pérez López, op. cit.

14 Miranda, op. cit.

15 “Cuban Pitcher Burns ’Em In.” The Sporting News, May 11, 1944: 30.

16 Daniel, Dan. “Ban on Recruiting by Majors Sought by Cuban Sports Chief.” The Sporting News, December 7, 1944: 4.

17 Pérez López, op. cit.

18 The Sporting News Baseball Register, 1952: 189.

19 Pérez López, op. cit.

20 Miranda, op. cit.

21 In the winter of 1947-48, another rival league would play at La Tropical, but this time it was the “outlaw” circuit. La Liga Nacional would also last just one season.

22 “N.Y. Cubans Beat Havana in Five-Game Exhibition.” The Sporting News, October 22, 1947: 7.

23 “Cubans 4, Sun Sox 0.” Associated Press, June 26, 1949.

24 “Senators Buy Julio Moreno.” Associated Press, July 23, 1950.

25 Hall, Dan. “Senators-Bound Moreno Defeats Saints, 6-1.” St. Petersburg Times, August 23, 1950: 15.

26 Pérez López, op. cit.

27 González, Gaspar. “El Lanzador.” Miami New Times, April 18, 2002.

28 Pérez López, op. cit.

29 Ruiz, Horacio. “Only 20,185 See Leon Cop Title Series.” The Sporting News, February 17, 1960: 30.

30 Hernandez, Roberto. “Puebla Fires Diaz; Moreno New Pilot.” The Sporting News, June 22, 1960: 36.

31 Ruiz, Horacio. “Smokers Snuff Out Injuns’ Bid for League title.” The Sporting News, February 14, 1962: 31.

32 Frau, Miguel J. “Crabbers Cop Latin Title Fourth Time in 14 Years.” The Sporting News, February 21, 1962: 37.

33 Ruiz, Horacio. “Julio Moreno to Pilot Leon Club in Nicaraguan League.” The Sporting News, November 10, 1962: 24.

34 “Moreno Goes on Sidelines.” The Sporting News, August 17, 1963: 34.

35 Hernandez, Roberto. “Puebla Parrots Rulers of Roost in Peso Circuit.” The Sporting News, August 31, 1963: 35.

36 Ruiz, Horacio. “Eaddy Snaps Out of Bat Slump, Paces Estrellas to Title.” The Sporting News, February 16, 1964: 29.

37 Ruiz, Horacio. “Loss of Scott Triggers Hot Boer Protest.” The Sporting News, October 29, 1966: 43.

38 Ruiz, Horacio. “Boer Belted By Estrellas In Playoff.” The Sporting News, February 4, 1967: 38.

39 Spoelstra, Watson. “Tigers Give Kid Firemen Early Tests.” The Sporting News, April 27, 1968: 10.

40 Spoelstra, Watson. “Tigers Doff Caps to Stanley, Stickout in CF.” The Sporting News, August 31, 1968: 11.

41 “At Last, Moreno Gets Slice of Series Loot.” The Sporting News, November 9, 1968: 40.

42 Spoelstra, Watson. “Mayo Warns His Bengals: ‘Don’t Turn Into Fat Cats.’” The Sporting News, December 21, 1968: 28.

43 González, op. cit.

44 Miami New Times, Letters from issue of May 2, 2002.

45 Pérez López, op. cit.

46 González, op. cit.

47 Pérez López, Luis. “El Jiquí Fue Símbolo del Mejor Baseball.” El Nuevo Herald, January 4, 1987. Sports-11.

Full Name

Julio Moreno González

Born

January 28, 1921 at Güines, (Cuba)

Died

January 2, 1987 at Miami, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.