Jean-Pierre Roy

This French-Canadian pitcher roamed widely but played just three big-league games in his career. During that one adventurous year, 1946, Roy hopscotched around Cuba, Mexico, Brooklyn — and his birthplace, Montréal. There Jackie Robinson played behind him as Branch Rickey’s “Great Experiment” moved forward. Then came a repercussion from Jorge Pasquel’s flashy raids. Roy jumped but never played for the Mexican magnate in ’46. He was not ineligible — but back in Cuba that winter, other men were. Guilt by association got him suspended from Organized Baseball in 1947. With a little patience, he might have had more time in the majors, but to this day the bon vivant has no regrets.

His six weeks with the Dodgers form the main entry on Roy’s itinerary. There was far more from 1940 to 1955, though: along with the minors, he spent six winters in Cuba, plus time in Québec’s Provincial League. Other stopovers included a notable winter in Panama, a return visit to Mexico, and a brief taste of the Dominican Republic. For a time after his reinstatement, Jean-Pierre also moonlighted as a nightclub singer while playing in Hollywood!

As a player, Roy enjoyed his greatest success at home in 1945. He later served the Montréal Expos from their inception through 1983 as one of their French-language broadcasters. A charming gent, always impeccably dressed and groomed, he remains with us as of 2008. In his late eighties, he remembers all his lightly picaresque tales well.

The Jean-Pierre Roy story begins on June 26, 1920. He was born on rue Adam, close to where Olympic Stadium was later built. In 2004, speaking to journalist Ronald King, Roy recalled that a hill stood on that very spot. As a boy, he and his friends would slide down the slope during the winter. In summers, they climbed the hill as baseball teams from the Hochelaga-Maisonneuve neighborhood faced squads from the Rosemont district. [1]

Roy’s father, Henri, was a legal clerk in the Circuit Court of Montréal. His mother stayed at home with her two children, Jean-Pierre and his younger sister Pierrette. The boy attended the local elementary school, École Chomedey-de-Maisonneuve. After that he went to a boarding school about 25 miles north of Montréal, Collège de l’Assomption.

“I started to play ball there,” Roy recalls. “Also, in the summertime, I used to play with other local teams. It was interleague play in a semi-pro regional organization.” His favorite catcher in those days was a young man named Jean Duceppe, [2] who became a leading Canadian actor, founded a thriving Montréal theater company, and fought for Québec’s sovereignty.

In September 1939, Canada entered World War II, and Jean-Pierre joined the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. “It was part of my national service. I had to report somewhere, and it was either that or the Army or the Royal Canadian Air Force. And I like to stay on the ground!”

Roy began his professional career in 1940 in Trois-Rivières (Three Rivers). This city is about 82 miles northeast of Montréal as one follows the St. Lawrence River. Marcel Dufresne, vice-president and part owner of the Rénards (Foxes), signed the young righthander to his first contract. [3]

The Provincial League of Québec had a curious on-off relationship with Organized Baseball over several decades. In 1940 it was a Class B circuit, though, and former big-league catcher Wally Schang was the Rénards’ manager. His slim rookie (5’10” and 160 pounds) posted a record of 10-8 with a 3.23 ERA. The season started with six teams, but war conditions caused two to fold. Trois-Rivières finished last among the survivors with a 37-42 record, yet still emerged as the league champion. First-place St.-Hyacinthe quit after losing the first playoff game because of four straight rainouts — “war and bad weather played havoc with all bankrolls.” [4] In the finals, the Rénards then beat third-place Granby four games out of five.

Jean-Pierre stayed with Trois-Rivières in 1941, but the franchise was now part of the Canadian American League (Class C). He went 14-13, 3.93. In the spring of 1942, Marcel Dufresne made a deal with the St. Louis Cardinals, who acquired Roy for $1,500. [5] He played with three of their farm clubs: Mobile in the Southeastern League (Class B), Houston in the Texas League (Class A1), and Rochester in the International League (Class AA). His won-lost marks were 7-3, 2-1, and 3-5; his ERAs were 4.21, 1.04, and 3.62.

The winter of 1942-43 marked Roy’s first visit to the Caribbean, as described by Cuban baseball author Jorge Figueredo:

“As the American involvement in World War II intensified and transportation became restricted, no U.S. players traveled to Cuba for this season; nor were teams allowed to train in the island. However, two Canadians, pitchers Paul Calvert and Jean Paul [sic] Roy were permitted the trip and joined the Cienfuegos staff, their first of several appearances in years to come.” [6]

Cuban pitcher Tomás de la Cruz, whom Roy knew as an opponent in Syracuse in 1942, “was the one who got me interested in going down there.” The native French speaker found it relatively easy to learn Spanish, and he soon became fluent. He was treated like a king in Cuba and loved the atmosphere and competition in the winter leagues. Although Jean-Pierre was just 1-5 in nine games in his first Cuban campaign, Figueredo notes, “He was quite a popular player.” The feeling was mutual; to this day Roy holds a deep affection for the Cuban people.

Back stateside, the 1943 season wasn’t pretty for Jean-Pierre. He split time between Rochester and Sacramento in the Pacific Coast League. Rochester manager Pepper Martin noted that Roy “had plenty of baseball ability but the wrong mental attitude.” [7] For the Red Wings, he went 2-8, 5.61, though he did throw a seven-inning one-hitter against Toronto in the nightcap of a doubleheader on May 31. For the Solons, he went 1-8, 4.81.

In 1944, after just two games in Cuba, Roy was back in Rochester. On June 2, though, business manager Guy Alrey suspended him indefinitely without pay. The Sporting News reported, “He packed his grip and left the stadium in a huff an hour before game time and said he was going to his home in Montréal. An effort will be made to trade him.” [8] A disagreement with Red Wings manager Ken Penner was the main reason, plus a fondness for the nightlife. [9] In later life, the ladies’ man said of this tendency, “I will never deny it. I don’t regret it, but I ought to have paid more attention.” [10]

Hector Racine, president of Roy’s hometown Montréal Royals, bought the pitcher’s contract for a mere $1,000. At the end of June, he had won just two games, one with the Royals. Being at home, however, helped him lift his game — along with a sliding bonus clause for wins. [11] He finished the year with totals of 12-11, 3.78. Branch Rickey, general manager of the parent club, the Brooklyn Dodgers, started to take notice.

Hernia surgery that winter cost Jean-Pierre the Cuban season, and it was also why he was rejected again for Army service. [12] “I played the whole season in 1944 with a double hernia. The Dodgers encouraged me to get the operation.”

Once recovered, Roy went on to enjoy easily his best pro season in 1945. He led the International League in wins: an all-time club record of 25, against 11 losses, with a 3.72 ERA. His 139 strikeouts (and 150 walks) were also more than anyone else in the IL. “Pete,” as Anglo fans and writers also called him, worked several doubleheaders and frequently served as a pinch-hitter too.

Montréal’s attendance led the league that year, fueled by a first-place team (95-58) and the presence of two other stars born and bred in the city: third baseman-outfielder Roland Gladu and shortstop Stan Bréard, who both also played with Jean-Pierre in Cuba. Gladu was another man whose brief major-league career (21 games with the 1944 Boston Braves) was just one facet of a long life in baseball. He said of Roy, “He had a great curveball that was really wicked.” [13]

That group had a broader impact too, notes longtime Expos broadcaster Jacques Doucet. “They put the seed in the ground for the next generation of major-leaguers from the province, guys like Claude Raymond and Ron Piché. There had been French-American ballplayers in the majors before, but not many French-Canadians.”

The Dodgers actually purchased Jean-Pierre’s contract along with Roland Gladu’s late that September, but the Canadians didn’t go to Brooklyn because the playoffs were still going. The pennant-winning Royals beat Baltimore in the first round. Roy dropped the opener, a 5-0 loss that was a 1-0 duel into the ninth inning. He was knocked out of the box in the second inning in Game Four, a 19-4 rout. In the seventh game, however, he rebounded, pitching into the sixth to win 4-1 before an overflow crowd of 22,500 at old Delorimier Downs.

Montréal then lost the Governors’ Cup to Newark. The Bears won the first three games, with no decision for Roy in Game Two — but behind him the Royals then climbed out of the hole. In Game Four he won with three hitless innings in relief, and he came back the very next day to pitch “a masterful two-hitter”, as the Associated Press described it. Two days later, as a pinch-hitter, he had an RBI double and scored the tying run as Montréal pulled off a wild 11-10 comeback from nine runs down. Unfortunately, Jean-Pierre lost Game Seven 5-1 as his fielders committed three errors in the seventh inning. [14]

In the winter of 1945-46, Roy pitched again in Cuba, where he was also known as “Jim” (easier to pronounce in Spanish). His club, the Cienfuegos Petroleros (Oilers), won the league championship. Managed by Adolfo (Dolf) Luque, the roster was full of talent. Even though he was near the end of his career, Hall of Famer Martín Dihigo was still the finest all-around player Jean-Pierre ever saw. Roy witnessed Dihigo play every position in a single game at least once at home, as “El Inmortal” also did in the Negro Leagues. The shortstop was strong-armed Silvio García, while Napoleón Reyes came over from Almendares to play first. Both men went into the Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame (in exile), as did pitchers Luis Tiant, Sr. and Adrián Zabala. Sal “The Barber” Maglie, who learned the arts of pitching and intimidation from Luque, was also on the staff.

Roy himself — limited to pitching once a week by Branch Rickey [15] — contributed a 5-5 record. This included two tough complete-game losses to Almendares. On December 18, Ray “Jabao” Brown (Cooperstown 2006) beat him 2-1, while on January 14, the Alacranes scored the game’s only run in the ninth inning. The opposing pitcher that day was another Cuban Hall of Famer, Jorge Comellas. Jean-Pierre’s best win that year was a 2-1 decision over Havana and Manuel “Cocaína” García on February 7. Again he went all the way.

It was quite likely this game that prompted Bernardo Pasquel to give Roy a gold watch. The Sporting News reported that he showed up at the Dodgers camp in Sanford, Florida on February 23 sporting the lavish timepiece. This was a typical gift from the wealthy Pasquel brothers, who had launched their bid to catapult the Mexican League to major-league status. [16]

Roland Gladu, who played outfield for the Cienfuegos champs, had already cast his lot with the Pasquels. Rickey’s comment in the New York Times on February 24 was, “Gladu’s case is different from [Luis] Olmo and Roy. Gladu is not, nor will he be, a major league player. He is 32 years old and the offer he received was very tempting. I don’t blame him for accepting it.” [17]

Although he had reportedly already accepted $4,000 to play south of the border, Roy inked a Dodger contract after a 15-minute talk with Rickey. He then flew back to Montréal for his sister’s wedding, after which he rejoined the Dodgers in Daytona Beach. [18]

The intrigue continued. On March 23, the New York Times reported “renewed overtures” from Mexico, in the shadowy person of one Robert Janis (real name Jamiez, according to Roy). [19] During the off-season, said The Sporting News, Giants outfielder Danny Gardella worked with Janis in the Manhattan gym that Jorge Pasquel frequented while in New York. Pasquel engaged Janis as a “scout.” The report continued, “Janis is the one who induced Gardella to jump the Giants in Miami and it was he whom Branch Rickey ordered chased out of the Dodgers’ camp at Vero Beach.” [20]

Less than two weeks later, though, Jorge Pasquel lowballed Roy. The Times quoted him on April 4: “As to the player Jean Pierre Roy, I have not offered him a new contract. I am ready to sign him up for $6000 a year and I telegraphed him to accept or to return to me the $3,300 advance on his salary which I have given him.” [21]

Jean-Pierre opened the season with Brooklyn, but his only major-league action came in one week from May 5 to May 11. He pitched a clean two-thirds of an inning with runners on base in his debut at Forbes Field. His one start came against the Reds at Crosley Field on May 9; he left in the fifth down 3-0, but the Dodgers rallied to get him off the hook. Finally, at Ebbets Field, he got another no-decision as the Dodgers outlasted the Phillies 12-11. Roy’s ERA was 9.95 in 6 1/3 innings pitched, with six walks and two homers allowed.

The Sporting News wrote, “What ‘soured him up’ on the club was the wearisome hours of riding the bench and pitching batting practice. Three times, he said, he asked to be returned to the Montréal Royals, but on each occasion the request was turned down by Rickey. Finally in desperation, he telephoned Bernardo Pasquel and asked him if the offer was still open. ‘Remember,’ Roy insisted, ‘I went to them this time, they didn’t come to me.’” [22]

Jean-Pierre signed for a reported $15,000. In addition, he was allowed to retain the bonus he’d gotten before. The Dodgers were paying him just $5,000 — plus they’d given him another lump-sum payment of $3,000 in February. (They also offered a good chance to go to the World Series, though of course they lost the pennant in a playoff to St. Louis that year.) [23]

In late May and early June, both the Montréal Gazette and the New York Times had coverage of the homesick Roy going AWOL to Montréal, followed shortly thereafter by his flight to Mexico. [24, 25] Just one day before the news broke that he had jumped, the Times said, “Brooklyn officials laughed at the rumor” [26] — but it was no bluff.

Less than two weeks later, though, Jean-Pierre was back. “He blasted the Pasquel brothers left and right, said that opportunity in Mexico was a myth.” Roy said that Jorge Pasquel — who kept a six-shooter at his elbow — reneged on his offer. Conditions were poor, with scarce showers and candlelit hotel rooms. Attendance was weak. [27]

Jean-Pierre adds, “The league wanted to spread the talent around. I was sent to San Luis Potosí, which was owned by a man named Pitman. [Dr. Eduardo Quijano Pitman, a dentist, succeeded Jorge Pasquel as president of the Mexican League in 1948.] I didn’t like it there. I did go back to Mexico later for personal reasons, though — I had met somebody and wanted to see her again.”

Roy rejoined the Royals in Newark on June 15, as Branch Rickey finally granted his wish. “Rickey was mighty nice. The first thing he did was shake my hand. I told him I didn’t want to be bawled out. He said we better sit down and talk things over. We did for about five hours. Finally I said I wanted to play for Montréal but not for Brooklyn. So here I am.” [28] He did wind up disgorging the Mexican bonus, though.

When asked what it was like playing for manager Leo Durocher with the Dodgers, Jean-Pierre responds, “I didn’t leave Brooklyn on account of him — it was because I wanted to pitch, I wanted some action! I liked playing for Leo, we became friends. He dressed very well, I did also — and he was a ladies’ man as well!”

Over the remainder of the ’46 season, Roy went 8-5, 5.59. Overwork the prior year may have taken too much toll on his arm, and he only got to pitch one inning in the playoffs as Montréal easily captured the Governors’ Cup. [29] However, he had the pleasure of playing with Jackie Robinson. Despite the bad taste left by manager Clay Hopper, a hardcore racist from Mississippi who also called Roy “a French son-of-a-bitch,” [30] Jackie and his wife Rachel loved Montréal for the welcome they received. Jean-Pierre still remains in touch with Rachel Robinson. He joined her as she returned to Québec for at least two celebrations of her pioneering husband, in 1977 and 2006.

Roy went back to Cuba that winter, posting a 4-8 record. The lifestyle in Havana remained attractive, with an apartment in the upscale Miramar district alongside Roland Gladu and other North Americans such as Sal Maglie and pitcher Max Lanier. He was courting trouble, though, because these men and others had been suspended for jumping to Mexico. Lanier had reportedly shown Jean-Pierre the $50,000 bonus he’d received from the Pasquels (all in new $1,000 bills) at a breakfast in New York the previous year. [31] In February 1947, George Trautman, the new head of the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues, declared Roy and his Royals teammate Walt Nothe ineligible themselves. “Roy said he was fully aware of the consequences of playing with and against ineligibles in Cuba. He therefore has no complaint, feels no remorse.” [32, 33]

Jean-Pierre looked for work in Montréal and played ball in the Provincial League, which at that time was outside of the National Association. He won 12 and lost 5 for the league champs, the St. Jean Braves, also batting .304 while managing and playing part-time in the outfield. On July 23, The Sporting News reported that he was also serving as a sports commentator in Montréal. [34] In addition, he pitched in one game for Rutland of Vermont’s Northern League.

The Royals reinstated Roy in the fall of 1947 — but then traded him in October to the Mobile Bears, another Dodgers farm club one level down in the Double-A Southern Association. Jean-Pierre declared he would not report. Instead, he stated his intention to play in Cuba once again and then with St. Jean in the Provincial League. [35] Roy was in Cuba’s Liga Nacional (or Players Federation), an “alternative” league featuring ineligible players that lasted just one year. It was his busiest season there, as he pitched in 25 games for three different teams: Cuba (2-7), Alacranes (7-2), and Leones (2-1).

Back in Québec, Roy was the Braves’ player-manager once more in 1948, going 19-9 (ERA again unavailable). This team had two other major-leaguers in Buster Clarkson, better known as a Negro Leaguer, and Bobby Estalella. He then spent his final winter in Cuba, going 3-3 with a 4.04 ERA for Cienfuegos.

Jean-Pierre returned to Montréal in 1949; however, he was just 1-1 with a 5.76 ERA for the Royals before moving to the Pacific Coast League. For the Hollywood Stars, he went 2-4, 4.50. Roy worked mainly in relief that year, pitching just 93 innings in 32 games. On August 24, The Sporting News observed that he was taking singing lessons. [36] Jacques Doucet chuckles, “He had to supplement his lowly baseball income!”

In November ’49, Roy joined the Rosabells, a team in California’s “Triple A” winter circuit that featured many minor-leaguers. Notable teammates included Dick Williams and Irv Noren. [37] Shortly thereafter, he went to Panama to play for the Carta Vieja Yankees, a team sponsored by a big local rum distillery. The manager was career minor-leaguer Wayne Blackburn. “I got a call from him in Hollywood and he invited me down,” says Jean-Pierre, who threw a one-hitter during the regular season. [38] Better yet, he helped Panama win its only Caribbean Series championship in February 1950.

The tournament was held in San Juan, and Carta Vieja staged an upset over the favorite, Almendares of Cuba, and the home team, Caguas of Puerto Rico. The Yankees tied the Criollos 4-2 in the round robin, which also featured Magallanes of Venezuela. They then took the playoff game. Roy beat Caguas in Game Four, 4-3; the switch-hitter helped himself by driving in the first two runs with a single. Winning before the vocal home crowd at old Sixto Escobar Stadium was no small feat. Cuba later defeated Jean-Pierre in Game 11, 8-0, breaking out for seven runs in the sixth inning. [39]

For the 1950 summer season, Roy rejoined Hollywood, where he went 2-2, 4.09. Off the field, he was also performing for a different crowd. The suave crooner’s nightclub act included numbers in English, Spanish, and French — “things like ‘Bésame Mucho,’ which was popular at the time, and ‘La Vie en Rose.’” Jean-Pierre recalled to Ronald King in 2004, “The manager, Fred Haney, didn’t like that. So I bought back my contract and went elsewhere.” [40]

In June, the Oklahoma City Indians (a Cleveland farm club that year) obtained the pitcher, who was just short of 30 years old. His record in Oklahoma was 0-5, 4.50, but that didn’t stop him from enjoying a winter on Mexico’s beautiful Sea of Cortez. It was the sixth season for La Liga de la Costa del Pacífico. Roy’s team was the Guaymas Ostioneros (Oystermen, after a local industry — think of John Steinbeck’s The Pearl). “A very notable person owned the club,” says Jean-Pierre. “His name was Zaragoza.” Don Florencio Zaragoza, from a prominent local family, was a great baseball promoter in the state of Sonora and a founder of the league.

Guaymas won the first half of the season in 1950-51. However, as Mexican baseball author Manuel de Jesús Sortillón notes, most of their imports left the team, and so the playoffs never took place. [41] Roy seconds this account: “The people were nice, but there was no money there. I was very fortunate to get what I got. All the good players, the Negro Leaguers and Cubans, went back home.”

Jean-Pierre remained in Mexico for a small part of the 1951 summer season, signing with the Mexico City Diablos Rojos (Red Devils). “I had purchased my contract from the Oklahoma club,” he notes. However, after just six starts and two relief appearances (1-4, 7.29 in 34 innings), he returned to the Provincial League. Splitting time between Trois-Rivières and Drummondville, he posted 18-15, 2.61 marks in 44 games. This helped him to sign with the Philadelphia Athletics organization for 1952. Ottawa of the International League was the A’s top farm club.

Jean-Pierre’s record there was 4-11, 3.99; in 2006, he said to journalist Martin Comtois, “I have good memories and less good memories.” The team wasn’t going anywhere, and there were only 15 games left to play in the season. The manager gave Roy permission to return home on family business. “The general manager hadn’t realized that. I was in my car listening to the radio when I heard that the team had suspended me.” [42] Meanwhile, Jean-Pierre stayed active in the independent Laurentide league near Montréal. [43, 44]

Roy wanted to return to Ottawa in 1953, but he was injured and sat out the season. He tried to make a comeback with the same team in spring training 1954, [45] but it did not work out. Then an opportunity arose in the Dominican Republic, where the league played in the summer from 1951 to 1954.

“Luis Olmo was a good friend of mine from the Dodgers. He was the manager in Santiago and invited me down. My arm was still not in good shape, so I told him, ‘It would be dishonest, I cannot give 100% of myself.’ Luis said, ‘Give me what you’ve got!’

“I liked the people, the weather was terrific, the food was good. But the first time out, I slipped in the dugout and hurt my elbow. I couldn’t give him a fair shake. So I was only there four or five days, and then I came back to Montréal.”

Jean-Pierre had one last fling in the Provincial League in 1955, going 3-3 in eight games (ERA unavailable) for Sherbrooke. On July 24, he staged an unusual stunt in Montréal as the Royals played the Havana Sugar Kings in a doubleheader. The “Pitchathon,” as Roy dubbed it, was his farewell to baseball. From 11 A.M to 5:45 P.M., throughout the twinbill, the 35-year-old threw in the bullpen — an estimated 2,835 pitches. He quit only because of blisters. One of his two weary catchers was the great National Hockey League goalie Jacques Plante. [46]

In 1956, Roy did some TV broadcasting for the Royals on CBF-TV. [47] He’d previously noted his intention to continue his nightclub singing career. Perhaps it was on a related note that he moved to Las Vegas, where he spent roughly 10 or 11 years in jobs ranging from croupier to real-estate agent.

Jean-Pierre visited Havana again briefly in 1958 while doing freelance radio work on some games against the Sugar Kings. In 2004, he recalled, “The Royals were there and we took on four different clubs in a week. Fidel Castro was in the mountains firing his guns. Cuba was controlled by the American Mafia. It was a fascinating place. . .a life of luxury, with hotels, nightclubs, casinos. We never had a problem. The Mafia was very discreet in those years.” [48]

In 1968, a new expansion franchise — the Montréal Expos — was preparing to join the National League. Jean-Pierre’s friend, the late Expos executive John McHale, brought him back from America, where he had become a citizen. [49] That September, the front office announced that it had hired Roy to drum up ticket sales. [50]. When the team started play, Jean-Pierre was in the broadcast booth, working as Francophone analyst on both radio and television.

One of his subtle contributions to the game was to refine the vocabulary of baseball in French, although Jacques Doucet observes, “We had a very solid base from the time of the Royals, even before O’Keefe Breweries got people together from all over Québec to work on this in 1968.

“One story I really remember about Jean-Pierre, though, is when Bill Stoneman threw his second no-hitter in 1972. It’s the only time we didn’t see eye to eye — Jean-Pierre was adamant that we could not mention it on the air while it was in progress! Claude Raymond was driving to Drummondville for a conference, and he missed the end of it. That was the first game of a doubleheader, and Carl Morton got off to a good start in the next game. I said, ‘Maybe we’ll see another no-hitter,’ and Claude shouted in his car, ‘Another one?!’ When Claude became my radio partner, I said, ‘Now can we talk about no-hitters?’

“But Jean-Pierre made what was a little awkward for me at first, coming over from a newspaper to be the number-one voice, into a smooth transition with no animosity. It became a very special relationship.”

Among other things, Roy directed a series of baseball clinics in Québec, along with Claude Raymond. This was part of a Canada-wide program the Expos had launched (circa 1971). [51] He also worked in a baseball promotion program with O’Keefe (circa 1973) [52].

Jean-Pierre remained on both TV and radio through 1973, maintaining his TV duties through the 1983 season. Although some sources note that he called some games in French for the Toronto Blue Jays in 1978, he states, “No, I never had anything to do with the Blue Jays.” Roy later served the Expos as a public relations representative from 1987 through 1989, keeping his hand in part-time for several years after that.

The Expos’ move made him heartsick. In 2004, he said, “I know Montréal is a great baseball town, but there are such negative aspects, the stadium, the politics, etc.” In his view, the club should have renovated its original home, Jarry Park. “It was perfect for baseball and well located,” Roy thought. “They could have built a dome. That was an error. In the big Olympic Stadium, one got lost.” [53]

Since retiring, the elder statesman of Montréal baseball has received several honors. In July 1995, he was inducted into the Expos Hall of Fame, and the Québec Sports Pantheon did likewise that September. In April 2001, the Québec Baseball Hall of Fame followed suit.

These days Roy spends his winters in Pompano Beach, Florida. He and his wife, Jane Duval Roy (his prior marriage ended with no children) head back north to Canada from May to October. There they live in the town of Nicolet, across the St. Lawrence from Trois-Rivières. Jean-Pierre has been working on an autobiography, and it will surely be a pleasure to hear this raconteur tell his own stories in full.

Grateful acknowledgment to Jean-Pierre Roy for providing his memories (telephone interviews on March 13 and 17, 2008) and to Ron Piché for his assistance.

Thanks also to the following SABR members (in alphabetical order): Merritt Clifton, Jacques Doucet, Bob Elliott, Jorge Figueredo, Kit Krieger, Daniel Papillon, Alexandre Pratt, Neil Raymond, Christian Trudeau, Alain Usereau, Bill Young, and Sam Zygner. Their prior research and helpful spirit made an integral contribution to this biography.

Notes

[1] Ronald King, “Le p’tit gars de la rue Adam,” La Presse (Montréal, Québec), July 13, 2004, p. S15.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Lloyd McGowan, “Two-Man Mound Corps Keeps Royals Rolling,” The Sporting News, June 21, 1945, p. 6.

[4] Jean Barrette, “Quebec Provincial League” in the Spalding-Reach Official Baseball Guide 1940, p. 233.

[5] McGowan, op. cit.

[6] Jorge S. Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2005), p. 315.

[7] Jim Shearon, “Jean-Pierre Roy, The Prodigal Son,” a section of the book Canada’s Baseball Legends (Kanata, Ontario: Malin Head Press, 1994), p. 115.

[8] The Sporting News, June 8, 1944, p. 24.

[9] McGowan, op. cit.

[10] King, op. cit.

[11] McGowan, op. cit.

[12] Lloyd McGowan, “Royals All Set to Field Team,” The Sporting News, January 25, 1945, p. 18.

[13] Shearon, op. cit., p. 116.

[14] Shearon, op. cit., pp. 116-117.

[15] “Four-Leaf Clovers for Birds,” The Sporting News, September 27, 1945, p. 20.

[16] “Roy in Detour to Mexico, Signs Brooklyn Contract,” The Sporting News, February 28, 1946, p. 2.

[17] Roscoe McGowen, “Pitcher Roy Signs Dodger Contract,” New York Times, February 24, 1946, p. 77.

[18] “Roy in Detour to Mexico, Signs Brooklyn Contract”

[19] Roscoe McGowen, “Mexicans Renew Overtures to Roy; But Dodger Pitcher Plans to Refund $4,000 He Accepted,” New York Times, March 23, 1946, p. 21.

[20] Dan Parker, “Gardella Met Pasquel in Gym, Rubbed Senor the Right Way,” The Sporting News, April 11, 1946, p. 5.

[21] “Mexican Is Ready to Bet $2000000,” New York Times, April 4, 1946, p. 42

[22] Lloyd McGowan, “Jean Roy, Soured by Bench Duty With Dodgers, Hikes to Mexico for Double His Major Salary,” The Sporting News, June 12, 1946, p. 17.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Shearon, op. cit., p. 118.

[25] “Dodger Suit to Enjoin Mexicans Upon Player Raids Is Dismissed; Owen Manages Veracruz During Bragana’s 30-Day Suspension–Ruth Starts Home–Roy Quits Brooklyn for Pasquels,” New York Times, June 1, 1946, p. 22.

[26] Louis Effrat, “Dodgers Triumph Over Giants, 5-1,” New York Times, May 30, 1946, p. 29.

[27] Lloyd McGowan, “Mexico Brings Disillusion, Roy Back in Royal Family,” The Sporting News, June 26, 1946, p. 14.

[28] Shearon, op. cit., p. 118.

[29] Shearon, op. cit., p. 119.

[30] William Humber, A Sporting Chance: Achievements of African-Canadian Athletes (Toronto, Ontario: Dundurn Press, 2004), p. 54.

[31] McGowan, “Jean Roy, Soured by Bench Duty With Dodgers”

[32] “Trautman Sets Down Roy and Nothe for Playing With Ineligibles in Cuba,” The Sporting News, February 26, 1947, p. 5.

[33] Lloyd McGowan, “Jean Roy, Barred by O.B., to Hurl in Canadian Loop,” The Sporting News, March 12, 1947, p. 16.

[34] Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, July 23, 1947, p. 36.

[35] Lloyd McGowan, “Roy of Royals Rebels Over Mobile Shift,” The Sporting News, November 5, 1947, p. 17.

[36] The Sporting News, August 24, 1949, p. 30.

[37] California Winter Loop Enrolls Minor Leaguers,” The Sporting News, November 16, 1949, p. 21.

[38] Leo J. Eberenz, “Sen. Johnson Visits Panama; Western League Head Sees Tilts on Ishtmus; Near No-Hitter by Jean Roy,” The Sporting News, January 4, 1950, p. 22.

[39] Santiago Llorens, “Panama Wins the Caribbean Pennant in Special Playoff,” The Sporting News, March 8, 1950, p. 25.

[40] King, op. cit.

[41] Manuel de Jesús Sortillón Valenzuela, www.historiadehermosillo.com/BASEBALL/Menuff.htm; see also Pedro Treto Cisneros, Enciclopedia del Béisbol Mexicano (Mexico City: Revistas Deportivas, 1998), p. 52.

[42] Martin Comtois, “Des moments inoubliables pour un lanceur ayant joué aux côtés de Robinson,” Le Droit (Ottawa, Ontario), July 22, 2006, p. 44.

[43] The Sporting News, August 20, 1952, p. 34.

[44] The Sporting News, September 24, 1952, p. 26.

[45] The Sporting News, April 7, 1954, p. 30.

[46] Lloyd McGowan, “Roy in 7-Hour ‘Pitchathon’ During Montreal Twin-Bill,” The Sporting News, August 3, 1955, p. 35.

[47] “Telecasts by Top Minors,” The Sporting News, April 18, 1956, p. 32.

[48] King, op. cit.

[49] Ibid.

[50] “Montreal Getting Organization Set,” Charleston (WV) Daily Mail, September 11, 1968, p. 14.

[51] Ian MacDonald, “Expos to Spend More Time on Tube,” The Sporting News, January 23, 1971, p. 44.

[52] Ian MacDonald, “Expos’ Kids Figure to Ripen Quickly,” The Sporting News, March 3, 1973, p. 32.

[53] King, op. cit.

Sources

SABR Québec website, http://quebec.sabr.org

http://www.rds.ca/baseballquebec/temple/roy.html

http://www.rds.ca/pantheon/chroniques/204858.html

Professional Baseball Players Database V6.0

Jorge S. Figueredo, Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball 1878-1961 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2007)

Raúl Diez Muro, Historia del Base Ball Profesional de Cuba, Havana, 1949.

Photo Credits

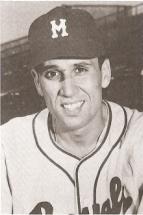

Roy as a Brooklyn Dodger: author’s collection

As a Montréal Royal: Montréal Gazette, from Shearon, op. cit.

Full Name

Jean-Pierre Roy

Born

June 26, 1920 at Montreal, QC (CAN)

Died

October 31, 2014 at Pompano Beach, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.