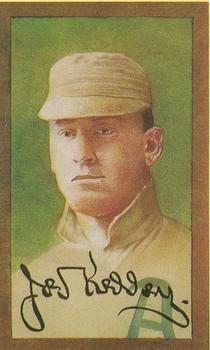

Joe Kelley

Outfielder Joe Kelley’s sensational play on the diamond earned him the well-deserved title “Kingpin of the Orioles.” He along with John McGraw, Willie Keeler, and Hughie Jennings made up the “Big Four” of the great Baltimore teams of the middle 1890s. Kelley was fleet of foot, sure-handed in the field, and blessed with a powerful throwing arm. At the plate, Joe was a prolific hitter who once connected for nine consecutive hits in a doubleheader.

Outfielder Joe Kelley’s sensational play on the diamond earned him the well-deserved title “Kingpin of the Orioles.” He along with John McGraw, Willie Keeler, and Hughie Jennings made up the “Big Four” of the great Baltimore teams of the middle 1890s. Kelley was fleet of foot, sure-handed in the field, and blessed with a powerful throwing arm. At the plate, Joe was a prolific hitter who once connected for nine consecutive hits in a doubleheader.

In the outfield, he was one of the best defenders of his day. Joe reportedly hid extra baseballs in the outfield grass on the sly in case the one in play got by him. Dubbed “Handsome Joe Kelley” by his multitude of female admirers in Baltimore, he kept a small mirror and comb in his back pocket in order to maintain his well-groomed appearance during games.

In a 1923 interview, Kelley’s former teammate and future Hall of Famer John McGraw told a reporter, “Joe had no prominent weakness. He was fast on the bases, could hit the ball hard and was as graceful an outfielder as one would care to see. He covered an immense amount of ground and had the necessary faculty, so prominent in [Tris] Speaker and others, of being able to place himself where the batter would likely hit the ball.”

Kelley played on six pennant-winning teams during his 17-year stint in the major leagues. He finished with a .317 career batting average, 443 stolen bases, .402 on-base percentage, and 194 triples. He knocked in 100 or more runs in five straight seasons and scored over 100 runs six times. Defensively, Joe was outstanding, posting a lifetime .955 fielding percentage in the outfield to go along with 212 assists. When his glory days on the diamond ended, he continued on in the game as a manager, scout, and coach.

The Hall of Fame Veterans Committee acknowledged Kelley’s stellar accomplishments on the ballfield by enshrining him in the hallowed halls of Cooperstown in 1971.

Joseph James Kelley was born on December 9, 1871, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His parents were Patrick and Ann (Carney) Kelley. The 1880 U.S. Census lists Patrick’s occupation as a marble cutter while showing six children living in the Kelley household. Joe’s mother and father, who were both born in Ireland, immigrated to the United States in order to escape the deadly famine that was ravaging their home country.

As a child, Joe received his formal education at a parochial grammar school in Cambridge that was run by a well-respected Catholic priest and Civil War veteran named Father Thomas Skully. From there, Kelley went on to St. Thomas Aquinas College in Cambridge, where he gained early fame as the school’s star pitcher. During this time, Joe was employed by a local piano manufacturer and later worked and played baseball for the John P. Lowell Arms Company.

In the spring of 1891, Kelley signed his first professional contract with Lowell of the New England League. Joe was a sturdily built lad at 5’11”, 190 pounds. He threw and batted right-handed. Lowell’s manager Dick Conway was so impressed with Joe’s all-around athleticism that he played him at every infield position and in the outfield on the days he did not pitch.

The Sporting Life of April 25, 1891, noted, “Lowell “cranks” are dead stuck on young Joe Kelley, who is pitching such fine ball for the local team.”

The fire-balling tosser finished the 1891 season with a pitching record of 10 wins and 3 losses while leading the league with a .323 batting average. The Lowell team folded in July, and at the end of that month the National League Boston Beaneaters gave Kelley a trial. Joe did not set the world on fire during his initial foray into major league baseball. He appeared in only 12 games for Boston, hitting just .244 and was not re-signed.

During the following winter, the Oakland Colonels of the Pacific League offered Kelley $1,200 to sign with the team. Joe turned down the deal, eventually signing with the Omaha Omahogs of the Western League for the 1892 season. He played in 58 games for the Omahogs, batting .316 with 19 stolen bases.

In July, Omaha sold Joe’s contract to the National League Pittsburgh Pirates. Kelley played with the Pirates until early September. At that time, the Baltimore Orioles new manager Ned Hanlon traded the team’s former player-manager, George Van Haltren, to the Pirates for Kelley and $2000 in cash. Joe initially declined to report to the Baltimore club and went back home to Cambridge, expressing concerns in the press over the financial solvency of his new team. After being given solemn reassurances from Hanlon that the franchise was in the black, Kelley finally relented and joined the Orioles.

Van Haltren was hitting .302 at the time of the deal, and Baltimore fans were none too happy about trading away such a good player for an unproven youngster who was barely hitting .200. “Foxy” Ned Hanlon was one of the game’s greatest strategists and innovators, as well as an astute judge of baseball talent. “I had my eye on Kelley for a long time,” Ned told the Baltimore Sun. The Birds skipper made Joe his personal project, scheduling private practice sessions at the ballpark, hitting him fungos and grounders while schooling him on the finer points of playing the outfield.

In 1893, the hard work started to pay off. Joe played great defense in center field and began to figure out major league pitching, hitting .305 with 27 doubles, 16 triples and 33 stolen bases. Late in the year, Kelley was moved from center to left field to make room for newly acquired speedster Steve Brodie. The Baltimore ballclub, thanks to Hanlon’s wheeling and dealing, showed improvement as well, climbing from last to eighth place in the 12-team National League.

The next season the Orioles and Kelley hit their stride. Joe posted career highs in hits (199), runs scored (165), doubles (48), triples (20), on-base percentage (.502), and batting average (.393).

On September 3, 1894, Kelley, batting leadoff, stroked nine straight hits in a doubleheader sweep of the Cleveland Spiders in front of a Labor Day crowd of over 20,000 fans at Baltimore’s Union Park. The hard-hitting Irishman put the finishing touches on his great day by slamming four consecutive doubles off Cy Young in the nightcap.

Kelley, along with John McGraw, and Hanlon’s latest acquisitions, Willie Keeler, Hughie Jennings, and Dan Brouthers played key roles in leading the Birds to their first National League championship in 1894. The Orioles faltered in postseason play that year, losing the first Temple Cup Series to the second-place New York Giants 4 games to 0. The Baltimore players were worn down from the numerous guest appearances they made after winning the pennant, and it showed in their play on the field. They also felt the meager payout from the series [$768 for the winning team and $360 for the losers] was not worth their time after the rigors of a long season. To offset the difference, many of the Orioles made deals on the side with Giants players to split the shares no matter who won the series. New York pitcher Amos Rusie paid Kelley $200 out of his winnings, but the other Giants refused to pay, claiming that they never made any such agreement.

In 1895, the Orioles copped the National League flag for the second year in a row. Kelley, who shared the team captaincy with catcher Wilbert Robinson, batted .365 with 54 stolen bases while establishing career highs in home runs (10) and RBIs (134). Defensively, he was now considered to be one of the best left fielders in the business. The Oriole players continued with their carefree attitude regarding postseason play, losing the Temple Cup Series once again, this time to the second-place Cleveland Spiders.

The following year, the Birds captured the National League title for the third consecutive time. Handsome Joe, as he was called by the throngs of female admirers in Baltimore who regularly flocked to the ballpark to see him play, batted .364 with a league-leading 87 stolen bases. The majority of Joe’s fans of the fairer sex sat in the left field bleachers at Union Park, which soon became known as Kelleyville.

The Orioles decided to take on their Temple Cup opponent more seriously in 1896, trouncing the second-place Cleveland Spiders in four games. Kelley, who hit .471 in the series, smacked a leadoff double in the seventh inning of the final contest to spark the Birds victory.

In early February of 1897, Joe signed on as the coach of the Georgetown University baseball team for the upcoming season. Kelley led the University men to the collegiate championship that year and according to the Washington, D.C., newspapers, made many friends in the Capital District.

Kelley, Keeler, and Hughie Jennings held out for higher salaries in the spring of 1897, and Hanlon had little choice other than to meet the demands of his star players. The Orioles put together another fine season that year, notching 90 victories but coming up two games short behind the pennant-winning Boston Beaneaters. Joe showed no ill effects from the pre-season holdout, slugging his way to a .362 average to go along with 44 stolen bases. In the fall the Birds defeated the Beaneaters in the final Temple Cup series, four games to one. Kelley came through again in postseason play, hitting .313 with 3 doubles and 5 RBIs.

There was a collective sigh of disappointment from all of the single ladies in Baltimore when Joe gave up bachelorhood and married local beauty Margaret Mahon on October 14, 1897. The wedding was held at the Mahons’ Derbyshire estate near Pikesville, Maryland. Father J. B. Boland from St. Vincent’s church and a number of other Catholic priests from around the area assisted in the service. Joe’s teammate Willie Keeler was the best man. The bride was the daughter of one of Baltimore’s prominent Democratic politicians, John J. “Sonny” Mahon, and was one of the most attractive debutantes in the city.

Joe and his new wife traveled to Cincinnati to join up with the rest of the Orioles who were in the early stages of a cross-country barnstorming trip called the All-American Baseball tour. The expedition involved members of the Baltimore club playing an aggregation of All-Stars from around the league in exhibition games in various cities all over the country. The transcontinental tour started in Hoboken, New Jersey, and ended up on the West Coast. The trip was actually a paid vacation for the players who were able to visit the scenic surroundings of each city on the tour while earning a few extra dollars on the side.

In 1898, Boston beat out Baltimore for the National League pennant by six games. Joe clubbed the ball at a .321 clip while leading the team in triples and RBIs. According to the New York Times, Kelley was making an annual salary of $2,500 with a $200 bonus for being the captain of the club. He received another $100 stipend if the Baltimore team finished in second place or higher, which it did.

When Joe, who was one of the best hitters in baseball, was asked if he preferred a certain type of bat, the confident Kelley replied, “It makes no difference to me what kind of bat I have. For instance, I often grab the first bat I come across when I go up to the plate. Muggsy McGraw uses a light stick and Jake Stenzel uses a heavy one, but I’m liable to take any one of the miscellaneous lot that falls in my way.”

The Orioles of this era were one of the first teams to employ the hit and run play, cut off man on relays, and many other innovative tactics. Manager Hanlon instructed his players on the importance of place hitting, bunting, and fouling off pitches during a time when fouls balls didn’t count as strikes.

Ned’s Birds were also a notorious bunch of umpire baiters who would fight at the drop of a hat and bend the rules when given the slightest opportunity.

Even Baltimore groundskeeper Tom Murphy chipped in with various acts of subterfuge. One of Murphy’s ploys involved burying a cement-like substance just below the dirt in front of home plate. The Oriole hitters would swing down on the pitch and when the ball hit the hard surface it would usually go straight up in the air. By the time it was fielded by an opposing player, the batter was well on his way to first base. This type of hitting was known as the Baltimore chop. Murphy also laid the fouls lines in the infield on an angle so bunts would roll back into fair territory. In the pre-rosin bag era, the crafty landscaper mixed in shards of soap in the ground surrounding the pitcher’s box. When a visiting tosser went to dry his sweaty hands in the dirt, he would get a fistful of slippery soil instead. The Oriole pitchers kept the good terra-firma in their pockets.

Hanlon’s charges weren’t averse to using psychological warfare against their opponents. Before home games, the Baltimore players were known to sit on a bench in front of the visiting team’s clubhouse, sharpening their spikes with metal files in plain view of the opposing players.

Kelley was extremely affable to the fans, but he was intensely antagonistic towards umpires and opposing players. When asked about the Orioles playing dirty baseball, Kelley replied with dry Irish wit, “We bathe as much as the next and this talk is all nonsense. The Baltimore boys only defend themselves when playing against teams that treat us mean, especially that bunch from Cincinnati.”

In February of 1899, Ned Hanlon, a major Oriole stockholder and the team’s president, orchestrated a deal that made him part owner and manager of Brooklyn’s National League team. Hanlon took most of his stars, including Kelley, with him to Flatbush. McGraw and Robinson declined to go due to their business interests at the Diamond Cafe in Baltimore. Joe, who had just bought a house in Baltimore, was not thrilled about leaving his new home and family. After asking Hanlon to trade him to Washington, which Ned refused to do, Joe grudgingly consented to the move.

The Brooklyn team was renamed in honor of a famous vaudeville act called Hanlon’s Superbas, and the team lived up to its name in every way. Brooklyn captured the National League flag by eight games as Kelley hit .325 while knocking in the most runs on the team. Brooklyn’s outfield of Kelley, Keeler and Fielder Jones was considered to be the best in the National League.

The Superbas continued their dominance in 1900 by winning their second consecutive National League crown. Kelley, who was the team captain, batted .319 with 17 triples and once again led the club in RBIs. Brooklyn went on to defeat the Pirates three games to one in a postseason series that was sponsored by the Pittsburgh Chronicle Telegraph that fall.

Hanlon’s star-studded lineup did not perform up to expectations in 1901, slipping down to third place in the standings. Joe, who may have been distracted with notions of returning home to Baltimore’s new American League franchise, barely hit .300, while splitting time between first and third base.

In the winter of 1901-1902 rumors circulated that Kelley would be hired as the manager of the New York Giants. Joe ended the speculation by signing with John McGraw’s American League Baltimore Orioles for the upcoming season. Kelley also acquired some of the team’s stock, giving him a vested interest in the club.

As the 1902 campaign progressed, McGraw’s constant battling with umpires led to a suspension from the American League office. The disgruntled Oriole leader, with the club’s permission, resigned from the team in early July and joined up with the National League New York Giants. Kelley and Wilbert Robinson took over as co-managers of the Orioles. Speaking to a reporter about what it takes to have a successful team, Joe said, “ It was confidence more than anything that gave Baltimore three pennants. We never went into a game that we did not feel sure of winning, and when we lost we blamed it on hard luck or the umpires. We never gave any other team credit for being able to play ball and the result was that we were hard to beat. If I could get my team to be confident, I think we would work our way to the front pretty quickly.”

Unfortunately for Charm City’s baseball fans, Joe shared McGraw’s disdain for the American League front office and its umpires. Soon after McGraw’s departure, Kelley began negotiations with Cincinnati owner John T. Brush in regard to taking over as player–manager of the National League Reds. In order to free himself from his Baltimore obligations, Kelley sold his Oriole holdings to his father-in-law Sonny Mahon, who had been elected team president back in February. The Baltimore political boss turned baseball magnate, and with the addition of McGraw’s shares that he purchased a few weeks earlier, became the majority owner of the Baltimore Baseball club. Mahon then sold his Oriole stock to Brush and Giants owner Andrew Freedman, giving both men financial control of the ballclub. Brush and Freedman immediately began transferring the most talented Oriole players to their own teams, leaving the Baltimore roster in a shambles. The Birds did not have enough men to field a team versus St. Louis on July 17 and ended up forfeiting the game.

American League president Ban Johnson, acting in concert with Baltimore’s minority owners, invoked a league rule that enabled them to take control of the team, but the damage was already done. Johnson, in an attempt to get back at McGraw, relocated Baltimore’s American League franchise to New York the following year.

In a subsequent newspaper interview, Kelley stated that the Oriole team was over $12,000 in the red and his father-in-law [Sonny Mahon] was left with few options other than selling his team shares in order to pay off the ballclub’s debts. Ban Johnson even stated publicly that Baltimore was the only club in the American League that had not paid its expenses. Joe said that his father-in-law had tried to contact Johnson in order to find out the exact amount the Orioles owed and discuss any possible remedies, but the league president never responded. Kelley added that Mahon had offered to sell the Orioles stock to an American League buyer but once again there was no response from Johnson.

Brush’s Cincinnati team signed Cy Seymour and Kelley at the time of the stock transfer, with the latter taking over the role of player-manager. The struggling Reds played much better under their new leader, who batted .321, going 34-26 for the rest of the season.

Kelley’s Reds, now under new ownership, didn’t have much success for the next three years. Joe played every infield position and the outfield during that time. He hit .316 in 1903, but the heavy burden of managing took a toll on his batting average for the next few years in Cincinnati.

In November of 1905, Kelley resigned as manager of the Reds, saying in the press, “I am tired of being roasted. I had a great deal of hard luck while manager of the team and somehow or other couldn’t get the best out of the material I had at hand. Mr. Herrmann [Cincinnati Reds owner Garry Herrmann] has no claim on me and I will ask for my unconditional release. I do not care to play in the west anymore. My home is in the east and that is where I prefer to play.”

After entertaining offers to take over the Brooklyn club, Joe had a change of heart and signed back up with the Reds as the team’s player-manager. A short time later, he relinquished the managerial role to his mentor Ned Hanlon, who no longer wanted to manage in Brooklyn after receiving a $6,000 pay cut the previous season. Hanlon named Joe captain shortly after taking over the reigns of the Cincinnati club. Neither Kelley nor the rest of the team played up to their potential in what turned out to be an unsuccessful season for the Reds’ new manager.

In January of 1907, Kelley agreed to become the player-manager of the Eastern League Toronto Maple Leafs for a reported $5000 salary, the highest ever paid to a minor league player at that time. Toronto’s big investment paid early dividends as he led the club to a first-place finish. Joe played in 91 games for the Leafs, hitting .322 with 15 stolen bases.

When the season ended, the siren’s call of big league baseball was too much for Joe, and on December 10, 1907, he signed a two-year contract with the National League Boston Doves. Kelley’s deal called for an annual salary of $5500 and he would be the Doves player-manager and team captain. When asked about his good friend’s new job, Willie Keeler spoke to the press, saying “Kelley is well-liked by the players, which means that the Boston team will be hustling all year.” Actually, Kelley’s popularity with players had the opposite effect. The Doves, taking advantage of their friendship with Joe and his informal enforcement of team rules, played uninspired baseball for the entire season. Kelley was especially unhappy with the play of ex-New York Giants Bill Dahlen and George Browne, who he felt had laid down in a late season series against their former team. Joe appeared in only 73 games for the Doves, and his hitting (.259) was far below his standard.

The Boston team’s president George Dovey was disappointed with the lack of discipline on his ballclub and placed all of the blame on Kelley. Dovey wanted Joe gone, and he began to look for ways to get out of the second year of the deal. The embattled Boston manager was livid over Dovey’s failure to honor his commitment and threatened legal action through National League President Harry Pulliam. Kelley and Dovey eventually met in Baltimore, and an amicable agreement was reached between the two men. Kelley’s contract issue with Boston was settled, and he immediately signed with Toronto as player-manager for nearly the same salary he had been promised by Dovey.

Toronto’s management was elated to have their former skipper back in the fold, and he remained with the club for the next few seasons. Joe continued to play the outfield, but beginning in 1913 he relegated himself to managing from the bench.

An 11-game losing streak kept Kelley’s Maple Leafs from winning the Eastern League title in 1911. The following season the club managed to avoid any of the previous year’s pitfalls, capturing their second pennant under Kelley in what was now called the New International League.

In an effort to cut team expenses, the Toronto club released Kelley in December of 1914. Joe was mentioned as a possible managerial candidate for the New York Yankees, but he ended up taking the job as the team’s chief scout. Joe was very active in that capacity, once bringing seventeen pitchers into camp in 1916. He handled player negotiations on some occasions in addition to other front office and on field duties when necessary.

On December 9, 1925, Brooklyn Robins manager Wilbert Robinson added Joe McGinnity, Otto Miller, and Kelley to his coaching staff. Joe was with Brooklyn for only one season as he and McGinnitty were released from their coaching duties at the conclusion of the Robins’ dismal 1926 campaign.

Joe left organized baseball at this time but continued to follow the national game through local newspapers and by attending Oldtimers games in Baltimore. When Kelley was in his twenties, he and his brother owned a lucrative truck hiring business in Cambridge. During his time in Baltimore, Kelley worked as clerk at the Baltimore courthouse and was a member of the Maryland State Racing commission. Joe was also a well-known figure in local Democratic politics, working on behalf of his father-in-law Sonny Mahon.

After a yearlong illness, Joe Kelley passed away at his home in Baltimore on August 14, 1943 at the age of 71. His wife Margaret Mahon Kelley and two sons Joseph Jr. and Ward survived him. A third son, William, died from meningitis in 1924.

Joe Kelley’s funeral vigil was held at his house at 2826 North Calvert Street. After a high mass at St. Phillip and James Church, the old-time Oriole slugger was laid to rest at New Cathedral Cemetery in west Baltimore. Joe’s teammates John McGraw, Wilbert Robinson, and their manager Ned Hanlon, are also interred at this historic 19th century cemetery.

January 25, 2011

Sources

Alyssa Pacy, Archivist at the Cambridge, Massachusetts, Library.

Ray Nemec, for his much appreciated assistance with Kelley’s major and minor league statistics.

Fleitz, David L. More Ghosts in the Gallery: Another Sixteen Little Known Greats at Cooperstown. McFarland 2008.

Kirsch, George, Othello Harris, and Claire E. Nolte. Encyclopedia of Ethnicity and Sports in the United States. Greenwood, 2000.

Reidenbaugh, Lowell, and Joe Hoppel. Baseball’s Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, Where The Legends Live Forever. Random House Value Publishing, 1988.

Solomon, Burt. Where They Aint: The Fabled Life and Untimely Death of the Original Baltimore Orioles, Simon and Schuster, 1999.

Baseball-Reference.com

Pittsburgh Press 1905

The Daily Argus 1892

Sporting Life 1891-1918

Morning Herald 1893 – 1900

Baltimore Sun 1893-1943

New York Times 1899-1917

Washington Times 1902

Notes

From the outset of Joe Kelley’s professional baseball career, his last name appeared in the press as both Kelly and Kelley. Some modern day writers have surmised that Baltimore reporters added the “E’ to his last name in order to set it apart from the common Irish spelling. Soon after Kelley joined the Orioles in 1892, the “E” can be consistently found in the spelling of his last name in the Baltimore newspapers, continuing that way for the remainder of his life. Joe’s father Patrick’s last name is shown as Kelly in the 1880 census but his 1912 death notice in the Cambridge Chronicle has it spelled as Kelley. Misspellings are quite common in the U.S. Census but are rarely found in obituaries and death notices. Unless Joe’s father added an E to his last name, one has to consider the possibility that Kelley may have been the proper spelling.

Full Name

Joseph James Kelley

Born

December 9, 1871 at Cambridge, MA (USA)

Died

August 14, 1943 at Baltimore, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.