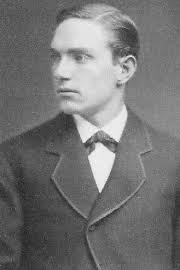

Asa Stratton

Worcester manager Mike Dorgan had a problem. It was June 1881, three months into the National League season, and his team, the Worcester Base Ball Club, was slipping toward the bottom of the standings.1 To make matters worse, his star shortstop, Arthur Irwin, had just been fined $25 for poor performance and granted a temporary leave of absence to — as the Worcester Daily Spy put it — “regain his confidence, health, and former playing ability.”2 The team asked Brown University’s slick-fielding captain, Asa Reed Dilts, to play short while Irwin recovered, but Dilts declined, unwilling to risk his college eligibility.3 With few other options, Dorgan turned to an unlikely substitute: his former teammate, Asa Stratton.

Worcester manager Mike Dorgan had a problem. It was June 1881, three months into the National League season, and his team, the Worcester Base Ball Club, was slipping toward the bottom of the standings.1 To make matters worse, his star shortstop, Arthur Irwin, had just been fined $25 for poor performance and granted a temporary leave of absence to — as the Worcester Daily Spy put it — “regain his confidence, health, and former playing ability.”2 The team asked Brown University’s slick-fielding captain, Asa Reed Dilts, to play short while Irwin recovered, but Dilts declined, unwilling to risk his college eligibility.3 With few other options, Dorgan turned to an unlikely substitute: his former teammate, Asa Stratton.

Asa Evans Stratton was born on February 10, 1853, in Grafton, Massachusetts. His parents, Cyrus and Eliza (Bosworth) Stratton, were members of the town elite,4 but their social status could not shield the family from the challenges of nineteenth-century life. In 1858 Eliza died after giving birth to a son named Charles,5 leaving Cyrus to care for Asa, Charles, and two older sons, George and Herbert. Charles died several months later from cholera.6 Cyrus remarried the following year,7 but his new wife, Almira Davis Brown, died from tuberculosis in 1861; their infant daughter Eliza (named for his first wife) died several months later.8 In 1862 Cyrus married Candace Elizabeth Sargent,9 but the Civil War — which had erupted in 1861 — soon intruded on family life: George enlisted in the Union Army in 1864 and served until the end of the war.10 Asa endured a difficult childhood, but the loss, separation, and uncertainty of his youth helped forge the man he later became.

In 1869, after studying at Grafton High School and prepping at Worcester Academy,11 Stratton entered Brown University, where he edited the school newspaper and joined the baseball team.12 Because baseball was a club activity, he and his teammates played only a handful of games each year and raised their own money to pay for equipment, travel, and uniforms.13 They practiced and hosted home games at the Dexter Asylum, a local institution that cared for the poor.14 Few records of Stratton’s college baseball career exist, but he was probably one of the team’s leading players, given his later success on the diamond. In 1873 he graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Brown and enrolled in the Boston University School of Law.15

Even as he studied law and prepared for the bar, Stratton emerged as one of New England’s top amateur ballplayers. From 1874-1875 he captained and played shortstop for his hometown team, the Graftons,16 which competed in the Massachusetts Association of Amateur Base Ball Players.17 In addition to Stratton, the team featured Dorgan, George Adams, Foghorn Bradley, and Hick Carpenter, all of whom went on to major-league careers. In 1875 the Graftons — “beyond doubt the best amateur nine in the State,” according to the Worcester Palladium — won the league championship, finishing with a 24-5-1 record.18 Stratton made 25 appearances, scored 40 runs, and averaged nearly two hits a game.19

When the Graftons disbanded after the 1875 season,20 Stratton took his talents to Lynn, Massachusetts, to play for the Live Oaks. On May 27, 1876, with an estimated 2,500 fans in the stands, the Oaks hosted the Syracuse Stars and the Stars’ new shortstop, Dorgan. A lame arm forced Oaks pitcher Foghorn Bradley from the game in the fourth inning, so Stratton took the mound in relief. “Though he [had] never pitched before, the Stars failed to make a base off him,” the New York Clipper reported.21 Thanks to Stratton’s strong performance, the Oaks beat the Stars, 8-3. According to the Clipper, “The result was a surprise, even to the Oaks themselves.”22 In addition to playing for the Oaks, Stratton umpired at least two college baseball games during the 1876 season.23

Stratton established himself beyond baseball, too. In 1875 he graduated from law school and joined the prestigious Staples & Goulding law firm in Worcester.24 Two years later he moved to Fitchburg, Massachusetts, to start his own practice, Gates & Stratton.25 In 1878 he married Ada Florence Bigelow, a sister of W.J. Bigelow,26 one of Stratton’s former Grafton teammates and, for one game in 1877, a major-league umpire.27 Asa and Ada, the children of Grafton elites, were the same age and had probably known each other for most of their lives. Their only child, Helen, was born in 1880.28 With the birth of his daughter, Stratton became — as the Fitchburg Sentinel later recalled — “a home-loving husband and father.”29

By 1881 Stratton was focused on his family and his law practice, not baseball. Although he continued to play for local amateur teams, including the Rollstones of Fitchburg,30 and might even have spent time with the Manchseters, which competed in the National Association,31 the 28-year-old lawyer must have been surprised when Dorgan asked him to fill in for Irwin, one of the NL’s top players. Whatever reservations he might have had, Asa Stratton — “famous as a shortstop in the days of the old Grafton team,” the Worcester Evening Gazette reminded its readers — was headed to the majors.32

On June 17, 1881, Stratton arrived at the Worcester Driving Park Grounds and suited up for his first — and only — major-league appearance. The Worcesters beat the Clevelands, 5-2, behind the pitching of Fred Corey (who gave up five hits and just one earned run), the defense of catcher Doc Bushong (who made two plays at the plate and threw out two runners at second), and the hitting of outfielders Pete Hotaling and Harry Stovey (both of whom singled, doubled, and scored two runs). “The remainder of the Worcesters played a steady game and did their batting when it counted,” the Daily Spy observed.33

But not Stratton, who struggled, especially in the field. Baseball had changed since he captained the Graftons, and he was out of practice. In the fourth inning, with one out and runners on first and second, Cleveland shortstop Jack Glasscock grounded to short. Stratton fielded the ball cleanly and turned to throw to Worcester third baseman Hick Carpenter. But Carpenter wasn’t there, and before Stratton could recover, the bases were loaded. The Evening Gazette explained — but did not excuse — Stratton’s mistake:

In the old Grafton days there would have been a man on 3d base to whom the ball could have been fielded, but in the modern game with runners on 2d and 1st bases and a sharp hit ball to short, the standard play is “short to second” sure and “second to first” afterward if possible.34

The Daily Spy agreed: “His play should have been to throw to second, and [second baseman George Creamer] would have made a double play at first.”35 Because of Stratton’s error, Cleveland scored two runs when the next batter, first baseman Bill Phillips, singled sharply to right field. Stratton did manage to single once in four at-bats against Jim McCormick, but he also struck out twice and committed a second error in the field.

Newspaper coverage of Stratton’s performance was harsh. The Chicago Tribune joked that Stratton “distinguished himself by striking out twice and missing an easy chance for a double play,”36 while the Providence Evening Press jeered that Stratton had “three chances and accepted only one,” a reference to his two errors.37 The Clipper opined that he “missed an easy chance for a double play which would have retired the Clevelands without a run.”38 Closer to home, the Evening Gazette mocked him for “dancing around with a ball in his hand, when a double play seemed easy.”39 And even the Daily Spy — the Worcesters’ semi-official newspaper — joined in the ridicule, quashing a rumor about Stratton’s relationship with the team: “The Gardner News says Asa Stratton was offered $2,500 this spring to play with the Worcesters during the season. What a story! He never was offered a penny.”40

Irwin returned to the team the next day; Stratton’s brief major-league career was over.41

Stratton returned home to Fitchburg and, for the next 40 years, was one of the city’s leading citizens. “He preferred to serve Fitchburg in his modest, inconspicuous manner,” the Sentinel observed. “The only public position which he would accept was that of a trustee of the Wallace public library,” which he held from 1917 until his death in 1925.42 In addition to his work for the library, he dabbled in local politics,43 served as a notary public,44 and sat on the Burbank Hospital board of trustees.45 He also took the field in an occasional local baseball game.46

Stratton’s greatest impact came as a newspaper editor. In 1885 he wound up his law practice and purchased the Gardner News, which he ran until selling it in 1895.47 He then became editor of the Fitchburg Morning Sun.48 In 1902 he joined the Sentinel, serving as city editor from 1905-1918 and editorial writer from 1918-1925.49 In these roles, he “attained an enviable reputation as an interpreter of the news and a writer of marked ability, an excellent music critic and a man whose high ideals and sterling qualities won for him the respect and admiration of all with whom he came into contact,” according to the Sentinel. 50 One of his library trustee colleagues called him “a creator and leader of … public opinion.”51

On August 14, 1925, Stratton died at his home in Fitchburg. He was 72 years old. Doctors listed his cause of death as “shock.”52 After a funeral service at his residence on August 17, Stratton was interred near his mother and father in Grafton’s Riverside Cemetery, where he was joined by Ada in 1926 and Helen in 1929.53

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Phil Williams and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Notes

1 The Worcesters finished the season in last place with a record of 32-50-1. They were 24-32 when the team decided to fire Dorgan on August 17.

2 “The Ball Field,” Worcester Daily Spy, June 14, 1881; “The Irwin Case,” Worcester Evening Gazette, June 14, 1881.

3 “Diamond Dust,” Providence Evening Press, June 18, 1881. For an example of Dilts’ fine fielding ability, see “The College Championship,” New York Clipper, May 21, 1881. In the spring of 1882, the New York Clipper speculated that Dilts might sign with either Worcester or Detroit for the 1883 season. “Metropolitans vs. Brown University,” New York Clipper, April 8, 1882. In the fall of 1882, however, Dilts enrolled as a student at Rochester Theological Seminary. “Baseball,” New York Clipper, October 21, 1882. He went on to become a Baptist minister and never played major-league baseball.

4 “Asa E. Stratton, Veteran Editor, Dies from Shock,” Fitchburg Sentinel, August 14, 1925.

5 Ancestry.com. Massachusetts, Death Records, 1841-1915 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2013.

6 Ibid.

7 Ancestry.com. Massachusetts, Marriage Records, 1840-1915 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2013.

8 Ancestry.com. Massachusetts, Death Records, 1841-1915 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2013.

9 Ancestry.com. Massachusetts, Town and Vital Records, 1620-1988 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

10 Historical Data Systems, comp. U.S., Civil War Soldier Records and Profiles, 1861-1865 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2009.

11 Arthur G. Freeland, ed. Delta Phi Catalogue (1908): 73.

12 Rick Harris, Brown University Baseball: A Legacy of the Game (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2012).

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid. Brown University purchased the property at auction in 1957.

15 Historical Catalogue of Brown University, 1764-1914 (Providence, RI: Brown University, 1914): 241.

16 Charles Nutt, History of Worcester and Its People, vol. 2 (New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Co., 1919): 1119-1121.

17 “The Massachusetts Amateur Championship,” New York Clipper May 22, 1875.

18 “City News,” Worcester Palladium, September 4, 1875; “Grafton (Mass.) Club,” New York Clipper, January 22, 1876.

19 “Grafton (Mass.) Club,” New York Clipper, January 22, 1876.

20 “Amateur Games,” New York Clipper, September 11, 1875.

21 “Live Oak vs. Star,” New York Clipper, June 3, 1876.

22 Ibid.

23 “Yale vs. Harvard,” New York Clipper, July 8, 1876; “Harvard vs. Yale,” New York Clipper, June 10, 1876.

24 “Asa E. Stratton, Veteran Editor, Dies from Shock,” Fitchburg Sentinel, August 14, 1925.

25 Stratton’s law partner was Charles B. Gates. Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

26 Gilman Bigelow Howe, Genealogy of the Bigelow Family of America (Worcester, MA: Charles Hamilton, 1890): 289-90.

27 “Boston vs. St. Louis,” New York Clipper, September 22, 1877.

28 Ancestry.com. Massachusetts, Birth Records, 1840-1915 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2013.

29 “Asa E. Stratton, Veteran Editor, Dies from Shock,” Fitchburg Sentinel, August 14, 1925.

30 Rick Harris, Brown University Baseball: A Legacy of the Game (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2012).

31 “Sporting Notes: Bits of Gossip Mostly Regarding Base Ball,” Worcester Evening Gazette, June 17, 1881.

32 Ibid.

33 “The Ball Field,” Worcester Daily Spy, June 18, 1881.

34 “Sporting Matters: The Diamond, the Track, the Range, the Course, the Field, the Ring, &c., &c.,” Worcester Evening Gazette, June 18, 1881.

35 Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

36 “Worcester 5; Cleveland 2,” Providence Evening Press, June 18, 1881.

37 “Worcester vs. Cleveland,” Chicago Tribune, June 18, 1881.

38 “Worcester vs. Cleveland,” New York Clipper, June 25, 1881.

39 “Sporting Matters: The Diamond, the Track, the Range, the Course, the Field, the Ring, &c., &c.,” Worcester Evening Gazette, June 18, 1881.

40 “Irwin back at shortstop,” Worcester Daily Spy, June 20, 1881.

41 Sporting Matters: The Diamond, the Track, the Range, the Course, the Field, the Ring, &c., &c.,” Worcester Evening Gazette, June 18, 1881. Irwin didn’t finish the season. On August 18, during the fourth inning of a game against the visiting Providence Grays, he broke his right ankle while sliding into second base. With no substitutes on the bench because of injuries, the team called Martin Flaherty out of the stands to play short. Like Stratton, Flaherty never played in the major leagues again.

42 “Asa E. Stratton, Veteran Editor, Dies from Shock,” Fitchburg Sentinel, August 14, 1925.

43 “Carlton and Doty Carry Fitchburg,” Fitchburg Daily Sentinel, April 1, 1908; “Dragged Out of Bed To Attend Caucus,” Fitchburg Sentinel, November 8, 1907; “Ready for the Caucuses,” Fitchburg Sentinel, September 13, 1906.

44 “Statement of the Ownership, Management, Circulation, Etc., of the Fitchburg Sentinel,” Fitchburg Daily Sentinel, April 3, 1916.

45 “Board All Right, System is Wrong,” Fitchburg Sentinel, January 17, 1917.

46 “Asa E. Stratton, Veteran Editor, Dies from Shock,” Fitchburg Sentinel, August 14, 1925; “Local Matters,” Fitchburg Sentinel, August 3, 1883.

47 “Asa E. Stratton, Veteran Editor, Dies from Shock,” Fitchburg Sentinel, August 14, 1925.

48 Ibid.

49 Ibid.

50 Ibid.

51 “Pay Tribute to Asa E. Stratton,” Fitchburg Sentinel, September 15, 1925.

52 “Asa E. Stratton, Veteran Editor, Dies from Shock,” Fitchburg Sentinel, August 14, 1925.

53 “Auto Accident Fatal to Miss Helen F. Stratton of High School Faculty,” Fitchburg Sentinel, September 16, 1929; “Mrs. Ada F. Stratton Dead After a Lingering Illness,” Fitchburg Sentinel, August 18, 1926.

Full Name

Asa Evans Stratton

Born

February 10, 1853 at Grafton, MA (USA)

Died

August 14, 1925 at Fitchburg, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.