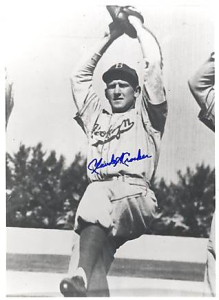

Claude Crocker

During World War II the major leagues pressed many very young players into service. The 1944 Brooklyn Dodgers were a leading example; they featured seven teenagers and three 20-year-olds. One of the men barely out of his teens was pitcher Claude Crocker, who went straight from the University of North Carolina to the majors. In 1945, Branch Rickey sang, “Great body control, fine fastball, perfect delivery, oh what a prospect!” Yet Crocker appeared in just three games for the Dodgers in 1944 and ’45. As with so many young pitchers, wildness and arm problems were his bane. He was finished by age 24.

During World War II the major leagues pressed many very young players into service. The 1944 Brooklyn Dodgers were a leading example; they featured seven teenagers and three 20-year-olds. One of the men barely out of his teens was pitcher Claude Crocker, who went straight from the University of North Carolina to the majors. In 1945, Branch Rickey sang, “Great body control, fine fastball, perfect delivery, oh what a prospect!” Yet Crocker appeared in just three games for the Dodgers in 1944 and ’45. As with so many young pitchers, wildness and arm problems were his bane. He was finished by age 24.

Claude Arthur Crocker was born on July 20, 1924, in Caroleen, North Carolina. This town is near the South Carolina border, west of Gastonia and Charlotte. Claude was the youngest of Horace L. and Lillie (Jones) Crocker’s three children. He had a brother named William and a sister named Virginia. Horace was a master mechanic who went to work at Clinton Mills, a textile company in Clinton, South Carolina, about 60 to 70 miles south of Caroleen. Lillie was a weaver by profession. For the rest of Claude Crocker’s life after his career in pro sports, Clinton remained home and “the Mill” was his primary employer.

Claude was a latecomer to baseball, according to the well-known sportswriter Hugh Fullerton. In July 1944 Fullerton wrote, “Claude (Rosebud) Crocker, University of North Carolina pitcher recently signed by the Dodgers, took up baseball two years ago to keep in shape for playing on a class B high school football team.”[1] In 2010 Crocker’s daughter and son, Virginia (Ginger) and Claude Adair Crocker, reminisced about their Daddy. “We are not sure about playing baseball as a young boy,” said Ginger. “If he did, it was probably just pickup in that his parents would not have had access to a YMCA league or anything like that.” Claude remembered his father’s dainty nickname, but not its origin.

At the University of North Carolina, Crocker was the No. 2 pitcher behind Clyde King, whose career in pro baseball spanned more than 60 years. Clyde and Claude remained lifelong friends. In fact, Crocker’s children made sure to keep in touch with him until his death in November 2010.

Crocker played football and basketball for the Tar Heels as well as baseball. Despite all that athletic activity, he was classified 4F for the draft – his children believed it was his knee – and thus didn’t go to war.[2] Frank Rickey, Branch’s bird-dog brother, discovered both Crocker and King in college; Branch Rickey gave Claude a $3,500 no-cut contract.[3] The Dodgers staff needed to be fortified, since Cal McLish (himself just 18) was due to go into the Navy.[4] The Brooklyn Eagle sniped at Rickey’s approach to fielding a team that year, calling his squad the “Kindergarten Corps” or “Diaper League.”

In 1983 King told author Dan Schlossberg about his roommate at Chapel Hill. “We signed at the same time, but he threw a lot harder than I did. Mr. Rickey worked very hard on trying to teach him to control the ball. One day he was coaching him while the whole team was looking. Mr. Rickey took off that hat he used to wear, laid it down on home plate, and said to Crocker, ‘You haven’t thrown a strike in your last 15 pitches.’ So Crocker wound up and hit that hat on the first pitch. That’s one of the few times I’ve seen Mr. Rickey speechless.”[5]

Crocker might just have been rusty, though, as the Associated Press reported on July 28. “Claude Crocker, North Carolina pitching product, reported to the Brooklyn Bums a day or two ago badly in need of work. Due to college exams he hadn’t pitched a ball in a month. ‘I thought I was in shape until I lost a running race out there in the outfield,’ puffed the youngster. ‘But I’m not used to running that way. I used to be a wingback, and I’m used to cutting to my left.’ ”[6]

Crocker made his big-league debut at Ebbets Field on August 1, 1944. The St. Louis Cardinals were leading 11-3 as Claude came on for Ralph Branca to start the eighth inning. Three outs later they were up 14-3. The nervous rookie walked four men and gave up two hits. Indeed, when he had reported, he said, “his best pitch was ‘a fast ball for college, but I don’t know how it will look up here. I’m as wild as a bug-rat.’ ”[7]

Five days later, as the home stand ended, Crocker again saw mop-up duty in the opener of a Sunday doubleheader. The Boston Braves scored 10 runs in the seventh inning and won 14-4. The last of those runs was charged to Crocker as he pitched the final 2 1/3 innings. He also singled in what would prove to be his only big-league at-bat.

Shortly thereafter, the Dodgers sent Crocker to Richmond on option – “possibly as part of the deal for [Ben] Chapman,” the New York Times reported.[8] Harold Burr of the Brooklyn Eagle sniffed, “Crocker had a fireball, but was just a thrower.”[9] With Richmond Claude was 1-3 in seven games, with 16 walks in 21 innings. Brooklyn recalled him along with 12 other minor leaguers on August 29, but he saw no further big-league action in 1944.[10] In September he pitched in the Piedmont League playoffs.

Before spring training in 1945, Claude and Clyde King returned to the University of North Carolina, playing with the Tar Heels’ “B” basketball team to keep in shape (something that might not be permitted today).[11] Crocker then reported to the Dodgers’ camp in Bear Mountain, New York. That spring was notable because Branch Rickey gave tryouts to African-American players Dave “Showboat” Thomas and Terris McDuffie. The Mahatma rated at least three pitchers above the 34-year-old McDuffie: Crocker, Vic Lombardi, and Frank Wurm. He declared, “Crocker had more speed, better changes of pace and far greater prospective ability for the major leagues.[12] It was at this time that Rickey rhapsodized, “Oh what a prospect!”

Despite Rickey’s praise and original indications that he would go to the Triple-A Montreal Royals, Claude went to Class C ball with Burlington in the Carolina League. The earnest young man had said, “Mr. Rickey, I’ll go any place. Send me down to Burlington, if you want.” It appears that Branch took him up on the offer, though he did say wistfully, “I wish I was a college coach again and had this boy, Crocker, on my squad. . . . You can talk about your Rex Barneys and your Hal Greggs. I expect to see Claude go even further.”[13]

At Burlington Crocker had an unremarkable overall record, going 9-11 with a 3.40 earned-run average. Along with intermittent arm problems, control was still an issue, as he walked 88 batters in 167 innings. Yet he still showed exciting flashes. In May, he struck out 14 and allowed just four hits in a complete game. On July 15 against Greensboro, he threw a no-hitter but lost 1-0 on a walk (one of seven he issued that day), an error on a bunt, and a wild pitch.[14]

“One story I remember Daddy telling,” Ginger Crocker said, “was about a time he was really throwing some wild pitches. The coach came out to talk to him, told him he was doing a great job, left the mound, turned around and came back, and told Daddy not to throw anything until he was back in the dugout.”

The Dodgers recalled Crocker in late September. On September 29 he dropped a 1-0 decision in relief of Art Herring to the Waterbury Brasscos in an exhibition game at Municipal Stadium in Waterbury. This Connecticut team – which included Yogi Berra and Spec Shea of the Yankees on its roster – had already beaten the Phillies 13-3 and the Yankees 1-0 in other in-season exhibition games that week.[15] The next day, against the Phillies at Shibe Park, Claude earned a save for Hal Gregg, pitching two scoreless innings as the Dodgers won, 4-1. He allowed only a pinch-hit single by Ben Chapman, who by then had become Philadelphia’s manager.

That was Crocker’s last big-league appearance. It would be intriguing to know what he had to say about his time in the big leagues, as well as Branch Rickey and manager Leo Durocher, but those thoughts (if he expressed them) have yet to be revealed.

During the winter of 1945-46 Claude attended Oak Ridge Military Institute in North Carolina and also reportedly had an operation on his troublesome knee (something his children believe may not have happened).[16] He was in the Dodgers’ camp again in 1946, and was impressive.[17] However, he spent the season with the Asheville Tourists of the Class B Tri-State League. Although he was just 4-4 with a 6.00 ERA in 18 games, Crocker was recalled to Brooklyn in September 1946, among 18 players – most notably Gil Hodges.[18] He didn’t see action in the heat of the pennant race, though neither did Hodges, for that matter. The Brooklyn Eagle wrote, “Claude Crocker and Ervin Palica will sit out in the Brooklyn bullpen.”[19]

Crocker played in parts of two more seasons as a pro. Because of arm problems, 1947 was a washout: just two appearances with Mobile in the Southern Association (Double-A). He then went back to Asheville, getting knocked out of the box in his first start there, on May 4.[20] At some point thereafter, he had a shoulder operation. “Daddy’s shoulder injury happened while it was raining and the game had not yet been called,” said his daughter Ginger. “He fell and tore his rotator cuff.” Claude did not return to the mound until late June 1948.[21] The results were not encouraging: 2-4 with a 6.89 ERA, giving up 60 hits and 41 walks in just 47 innings.

Thomas Perry, who chronicled the history of textile baseball in the Palmetto State, wrote, “By 1949 . . . nerve damage to his pitching arm cut short a promising career, and he accepted a job as athletic director at Clinton Mills, where he continued playing, becoming manager of the Cavaliers [the Mill’s industrial team in the Central Carolina League].”[22] Ginger Crocker offered more insight. “They were sending him down somewhere for it to get better and he came to see his parents in Clinton before going. When the president of Clinton Mills, Silas Bailey, heard he was in town; he went to see him and offered him a ‘real job’ at the Mill. He recruited Daddy to coach and play for his team in the Textile League.” According to Clinton historian Sam Owens, “Mr. Silas Bailey wanted big time baseball, so he had [Cavalier Ball Park] built to house a semipro textile team that could compete with any other.”[23]

“The salary Daddy was offered was much more than playing [minor-league] baseball and that is how he left the pros,” Ginger recalled. “In his generation, many men in South Carolina were baseball players working in the textile industry. None of them worked ‘in’ the mills because they might get hurt. They were all working in safety or human relations.” It was more than just a job, though. “His textile baseball years were very rewarding,” Ginger added. In addition, Claude coached the Clinton Mills basketball team.[24]

On October 17, 1950, Claude married Myra Adair, a lifelong resident of Clinton who graduated from nearby Winthrop College in 1950. They remained married for almost half a century but missed their golden anniversary when Myra passed away in July 2000.

In addition to the Clinton Mills team, Crocker was basketball coach at Presbyterian College in Clinton for one season, 1949-50. [25] That followed one season of coaching baseball there (he had previously been an assistant coach at UNC). Former major-league shortstop Walt Barbare replaced Crocker in 1950. The entire family became loyal supporters and benefactors of Presbyterian, a small private liberal-arts college. In 1966 Claude became president of the Walter Johnson Club, the alumni athletic organization of the Blue Hose.[26] This group is now known as the Scotsman Club, for the school’s mascot, a concept that Crocker helped dream up. “Apparently, it all started in the 1960s, when Ross Templeton and Claude Crocker, president of the Walter Johnson Club, created ‘Rufus A. Cobb’ (rough as a cob). Rufus was reputed to be part of a fierce Scottish tribe whose members wore blue stockings.”[27]

“He also donated the baseball field to Presbyterian College,” said Ginger, “but named it for the deceased son (at a very young age) of the athletic director at the time. Daddy would never have named anything for himself.” In 2000, the college awarded Crocker an honorary doctorate in public service, one of its primary missions.

During 2002 Presbyterian opened its Bailey Memorial Stadium. It hosts football rather than baseball, but the playing surface is called Crocker Field. “The football field is named for both him and his father,” said Ginger. “When Papa Crocker retired from the Mill, he became the equipment manager at the college. My brother and I donated the field and told Daddy we were naming it for his father. He did not know we were naming it for him as well until the dedication. He would have never allowed that had he known.”

Crocker became the Mill’s director of public relations and later vice president of human resources before retiring around 1998. Ginger said, “He was able to participate in a leveraged buyout of the plant [near the end of 1986], so he was indeed an owner of Clinton Mills, Inc. before his retirement. This, of course, was a great matter of pride for someone whose parents had worked there all their lives and had never graduated from high school.”

“Claude Crocker was a man that everyone in Clinton knew.”[28] He was a civic leader; in 1984 Governor Richard Riley awarded him the Order of the Palmetto, the state’s highest civilian honor. He was also active in statewide Democratic politics. In 1988, during the presidential primary season, the Associated Press quoted him as the candidates visited. “Claude Crocker said no topic is too big for his crowd. ‘We talk about international trade policy, the Panama Canal, the deficit. . . . We handle all those high-level things,’ the vice president of Clinton Mills deadpanned.”[29]

Claude Crocker died of pneumonia on December 19, 2002, at the age of 78. Among his many endeavors in life, one may best reflect his personal ethos. He served on the Governor’s Advisory Committee on workers’ compensation under four governors. Among other things, he studied a leading occupational hazard of the textile industry, brown lung. This cause clearly resonated in the family; his daughter became deputy commissioner and later judicial director of the South Carolina Workers’ Compensation Commission. Ginger reiterated, “Daddy cared deeply about working men and women.”

Grateful acknowledgment to Virginia L. Crocker and Claude Adair Crocker for their memories of their father.

Sources

Claude Crocker obituary, The State (Columbia, South Carolina), December 20, 2002: B4.

Myra Adair Crocker obituary, The State, July 18, 2000: B4.

www.baseball-reference.com

www.retrosheet.org

www.gobluehose.com

www.newspaperarchive.com

www.fultonhistory.com (Brooklyn Eagle)

Order of the Palmetto recipients: South Carolina state archives (http://archives.sc.gov/oopsilver.htm)

[1] Fullerton, Hugh. “‘Sinky’ Good For Shape He Is In.” Associated Press, July 21, 1944.

[2] McGowen, Roscoe. “Dodgers Beaten by Pirates, 10 to 1.” New York Times, July 10, 1944.

[3] Holmes, Tommy. “King Recrowned by New Pitch.” Baseball Digest, July 1951: 63; Perry, Thomas K. Textile League Baseball: South Carolina’s Mill Teams, 1880-1955. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1993: 73.

[4] Burr, Harold C. “Lip’s Job Safe – While It Lasts.” The Sporting News, July 20, 1044: 4.

[5] Schlossberg, Dan. The Baseball Catalog. Middle Village, New York: Jonathan David Publishers, 1983: 270-271.

[6] Howell, Fritz. “Sports Roundup: A Budding Dodger.” Associated Press, July 28, 1944.

[7] “Leo Grooms McLish as Third Baseman.” Brooklyn Eagle, July 25, 1944: 10.

[8] McGowen, Roscoe. “Dodgers Vanquish Great Lakes, 7-4.” New York Times, August 9, 1944.

[9] Burr, Harold C. “Sunkel Called Home.” Brooklyn Eagle, August 9, 1944: 12.

[10] “Dodgers Recall 13.” United Press, August 29, 1944.

[11] Fullerton, Hugh. “Sports Briefs.” Associated Press, March 7, 1945.

[12] “Two Negroes Are Tried Out by the Dodgers But They Fail to Impress President Rickey.” New York Times, April 7, 1945; “Dodgers.” Associated Press, April 8, 1945.

[13] Burr, Harold C. “Flock Plans to make Test of Draft Ruling.” Brooklyn Eagle, April 3, 1945: 13.

[14] The Sporting News, July 26, 1945: 16.

[15] “Dodgers Blanked, 1 to 0; Crocker Yields Run in Defeat by Waterbury Brasscos.” New York Times, September 30, 1945.

[16] The Sporting News, December 20, 1945: 17.

[17] John, Walter L. “Pitching Can Make Dodgers Contenders in 1946 Campaign.” Central Press, March 20, 1946.

[18] McGowen, Roscoe. “Phillies Checked by Melton, 5 to 2.” New York Times, September 3, 1946.

[19] “3 Dodger Farm Players Report to Ebbets Soon.” Brooklyn Eagle, September 3, 1936: 13.

[20] The Sporting News, May 14, 1947: 31.

[21] “Tourists Tie Own Run Record.” The Sporting News, July 7, 1948: 32.

[22] Perry, op. cit., loc. cit.

[23] Owens, Sam. Clinton. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2000: 98.

[24] Kirkpatrick, Mac C., and Thomas K. Perry. The Southern Textile Basketball Tournament: A History, 1921-1997. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1997: 180.

[25] After another year went by, Coach Norm Sloan took over Presbyterian’s basketball program for four seasons. He would later coach an NCAA champion team at North Carolina State that included future major-league pitcher Tim Stoddard.

[26] Long, Melvin. “Bob Kelly Tries Outfield.” Spartanburg (South Carolina) Herald-Journal, March 27, 1966: D1. Note: This Walter Johnson was Presbyterian’s athletic director, not the great Washington Senators pitcher.

[27] “School Spirit.” Blue Notes, Presbyterian College blog, September 2009 (http://www.presby.edu/library/archives/blog/?page_id=869)

[28] Owens, op. cit.: 121.

[29] Reed, David. “Pols invade South Carolina.” Associated Press, March 1, 1988.

Full Name

Claude Arthur Crocker

Born

July 20, 1924 at Caroleen, NC (USA)

Died

December 19, 2002 at Clinton, SC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.