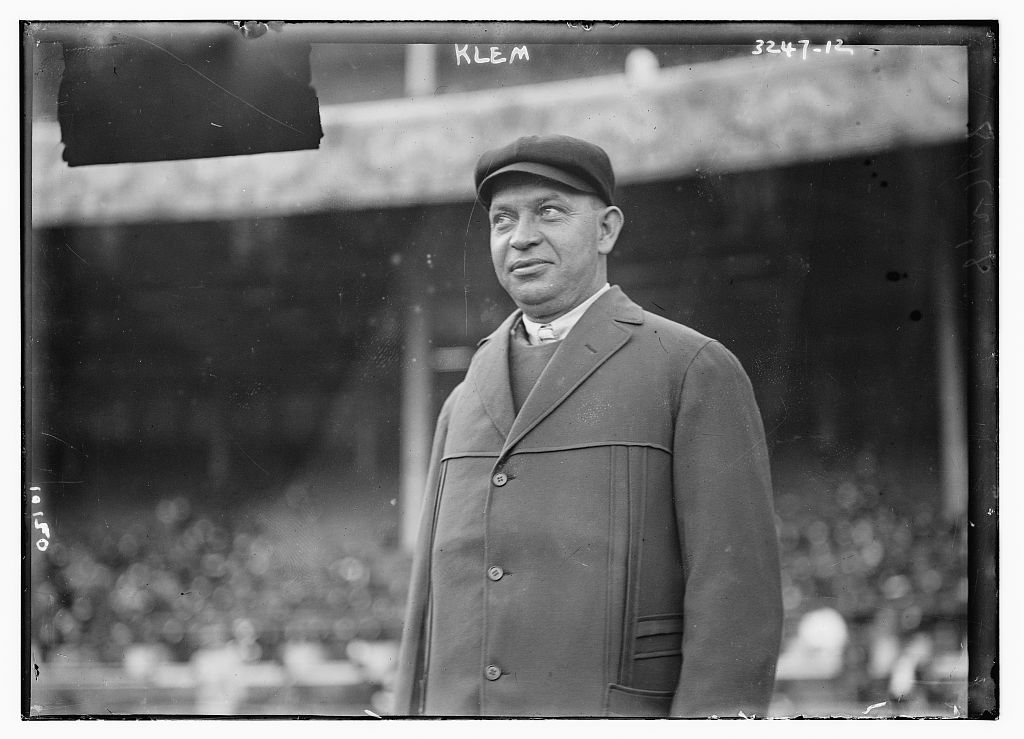

Bill Klem

Born on Washington’s Birthday in 1874 in Rochester, New York, William Joseph “Bill” Klem became one of the greatest umpires to ever take the field. “I was born of German parents in the Irish section near ‘Dutchtown’ in Rochester, New York,” Klem later said.1 Both father Michael Klimm and mother Elizabeth were from Bavaria. Bill was their eighth child. Michael Klimm worked as a wagonmaker. Bill himself, at the time of the 1892 New York State census, was 18 and working as a shoemaker.

Born on Washington’s Birthday in 1874 in Rochester, New York, William Joseph “Bill” Klem became one of the greatest umpires to ever take the field. “I was born of German parents in the Irish section near ‘Dutchtown’ in Rochester, New York,” Klem later said.1 Both father Michael Klimm and mother Elizabeth were from Bavaria. Bill was their eighth child. Michael Klimm worked as a wagonmaker. Bill himself, at the time of the 1892 New York State census, was 18 and working as a shoemaker.

Bill Klimm followed his uncle’s footsteps and changed his name to Klem (“I thought Klem had a firmer sound and was a better name for an arbiter.”) He went on to fame on the diamond in a profession that was hardly respectable when he entered it. Elected to the Hall of Fame in 1953, Klem is credited with helping upgrade dignity and respect for umpiring during a major-league career that spanned 37 years (1905-1941).

As with many of his umpire contemporaries, Klem first tried to be a professional ball player. In 1896 he tried out for catcher for the Hamilton, Ontario team of the Canadian League2, but a bum arm ended that hope. For the next few years Klem played semipro ball in New York and Pennsylvania and supported himself by taking construction jobs.3

His life took a turn in 1902 in Berwick, Pennsylvania when he tried his hand at umpiring a game between the New York Cuban Giants and a semipro team from Berwick. He was paid $5 for his efforts.4 While in Berwick, Klem read a newspaper account about Frank “Silk” O’Loughlin, a hometown friend, and how he was faring as a National League umpire.5 Reading about O’Loughlin influenced Klem to consider umpiring as a career, despite O’Loughlin’s trying to discourage him by saying, “This is a rotten business.”6 Indeed, Klem said that O’Loughlin introduced him to umpire Hank O’Day and said that he was an example of how the profession had turned O’Day into a “misanthropic” loner.

Nonetheless, Klem contacted “baseball man and old friend” Dan Shannon, who suggested that he talk to Sydney Challenger, in charge of hiring umpires for the Connecticut League. It was on Shannon’s recommendation that Challenger hired Klem. Two years later, in the spring of 1904, Klem ran into Hank O’Day again in New York. O’Day brought Klem to National League headquarters and introduced him to President Harry Pulliam. This led to Pulliam later hiring Klem as a major-league umpire. Klem put in three years in the minors, where he learned important lessons each step up the ladder.

Semipro work aside, Klem’s professional umpiring career began in 1902 in the Class-D Connecticut League. The pay was $7.50 for a single game and $10.50 for a doubleheader. Klem recalled it was a tough league and, “if the home team lost you got an awful amount of abuse with your money.”7 Here he began to develop his reputation for toughness on the field along with determination and a sense of fair play. The money must have offset the abuse because he took on the challenge of umpiring in the Class-B New York State League in 1903.

Klem found himself in hot water with team owners and fans on a number of occasions because of his enforcement of a new league policy of fining players on the spot for using abusive language toward umpires. Klem often defied owners who tried to keep him from officiating; this defiance was illustrated years later when Giants manager John McGraw told Klem he would have his job. Klem’s reply was if McGraw could have his job, then he did not want it.8

The 1903 season was not easy for Klem; he was the only New York State League umpire hired at the beginning of the year to last the entire season.9 His tenacity and courage were tested on an almost daily basis in a league, which refused to hire more than one umpire for a game.

Klem moved his services to the Class-A American Association in 1904, and immediately applied what he had learned and developed what umpire historian Larry Gerlach called the tough cop approach to umpiring. It was in the AA that Klem first drew a line in the dirt and told irate players and managers, “Do not cross the Rio Grande.” Those who did were immediately ejected.10

Automatic ejection was also Klem’s response to the nickname “Catfish.” The term was first used in the American Association as a commentary on Klem’s piscine appearing mouth. Klem hated the nickname and the mere use of the word within his earshot bought the offending party an early exit from the ballpark.11

During his year in the American Association Klem started getting attention from the big leagues. In the spring of 1904, Hank O’Day had introduced Klem to National League President Henry Pulliam.12 Learning he’d be working in the AA, Pulliam said, “I’m going to keep my eye on you, Klem.”13 Pulliam hired Klem to umpire a postseason National League exhibition game between Cleveland and Pittsburgh.14 It was this gesture that made Klem a loyal National Leaguer.

In 1905 Klem was offered $2,100 to umpire in the American League through the efforts of O’Loughlin. Although Klem wanted to umpire in the majors, he resisted the urging of other American League umpires and held out.

American League president Ban Johnson had the reputation of strongly supporting his umpires and trying to eliminate rowdy behavior, and one might have thought Klem would find the AL more hospitable. But both Johnson and Klem were strong, autocratic personalities who probably would have clashed both on and off the field.15

Klem was waiting for word from Pulliam, the man who gave him his first major-league assignment. His patience and loyalty paid off. Pulliam offered Klem a job and matched the American League offer. Klem remained a loyal National Leaguer for his entire career, referring to the Junior Circuit as “the hucksters of the big leagues.”16

Klem wasn’t a large man. He stood 5-feet-7 1/2 and is listed at 157 pounds. Klem’s first major-league game was on April 14, 1905 in Cincinnati as the Reds played the Pirates. He faced challenges establishing himself, as witness the 25 ejections in his first year in the league. In fact, he averaged more than 19 ejections over the course of his first seven seasons. In all, Klem ejected 279 persons during the course of his career, but after the 1915 season he only reached double digits once, in 1920.

In 1910, Klem married Marie Kranz, who he credited with helping him handle the stress of umpiring. With the couple being childless, Marie often traveled with her husband on the road. Regardless of any comfort Marie might have provided, Klem still developed a recurring skin condition attributed to the pressures of his profession.17

Klem’s last full year as umpire was 1940, but he worked 11 games in August and September 1941 as the National League experimented with four-man crews. Age was beginning to get to him. Late in 1940 he was hit by a ground ball in the infield and realized that he was slowing down at the age of 66. He umpired those 11 games in 1941 in his role of Chief of the National League umpire staff. Klem knew he was done when in a St. Louis-Brooklyn game he missed a tag. Klem said that was the first time he only thought, not knew, that a man was out .18

He remained head of National League umpires until his death in 1951. During his career he umpired in 18 World Series, taking part in 103 Series games, both all-time records.19 Klem called five no-hitters from behind the plate. He was the home-plate umpire in the first All-Star Game, in Chicago in 1933. He also worked the plate in the 1938 game.

He is credited with developing the inside chest protector, but Klem said that idea came from others. 20 He did claim credit for teaching umpires to work the “slot,” which he claimed gave umpires a better look at the strike zone by looking between the catcher and batter. 21 He is also among those given credit for developing a system of signals for safe, out, strike, fair, or foul ball. Klem himself took credit for developing a fair-foul signal during his 1904 stint in the American Association.22

Many histories say Klem was so good at calling balls and strikes that he was plate umpire for the first 16 years of his career. This is not entirely accurate, but for those 16 years (1905-1920), Klem worked behind the plate a remarkable 88.8% of his games, many of them solo. It was this impressive record that led to the myth that he worked exclusively behind the plate his first 16 years. Even after the two-umpire rule was introduced in 1911, Klem continued to work almost exclusively behind the plate for more than a decade. While many other umpires were rotating between working the plate and bases, Klem mainly worked behind the plate. He only began to take his regular turn on the bases in 1921. The major leagues did not hire enough umpires to guarantee two-man crews until the 1911 season.23 Hank O’Day has an even higher percentage (68%) of career games worked behind the plate than Klem (66%). Throughout his entire career, Klem would often work the plate when paired with a rookie umpire early in the season until the beginner gained experience.24

This one flaw in the historical record should not detract from a career that will probably be unmatched in baseball history. Anyone who umpires baseball at any level owes a debt to Bill Klem for his work in making umpiring an honorable profession.

This biography is included in “The SABR Book on Umpires and Umpiring” (SABR, 2017), edited by Larry Gerlach and Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 William J. Klem and William J. Slocum, “Umpire Bill Klem’s Own Story,” Collier’s Weekly, March 31, 1951: 30.

2 Klem also “had trials with professional teams in … Springfield, Massachusetts and Augusta, Maine, during the 1896-1897 seasons.” See Martin Appel and Burt Goldblatt, Baseball’s Best: The Hall of Fame Gallery (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1977), 250. In the first part of the Klem series in Collier’s Weekly (March 31, 1951), Klem says he tried out for the Hamilton, Springfield, and Augusta professional baseball teams.

3 Klem also worked as a painter, steelworker, construction foreman, bookmaker, and bartender. William J. Klem and William J. Slocum. “I Never Missed One in My Heart,” Collier’s Weekly, March 31, 1951: 30, 31.

4 Collier’s Weekly, March 31, 1951: 59.

5 See David L. Fleitz. The Irish in Baseball: An Early History (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Publishers, 2009), 119.

6 Collier’s Weekly, March 31, 1951: 59.

7 Collier’s Weekly, March 31, 1951: 62, 64.

8 Source for this is from “Jousting With McGraw,” the second part of the Collier’s Weekly “Bill Klem’s Own Story” series, April 7, 1951: 50. The exact quote: “Mr. Manager, if it’s possible for you to take my job away from me, I don’t want the job.” In the first part of the Collier’s series, Klem related another story in which he had a somewhat similar retort as a rookie umpire (1902). When manager Jim O’Rourke was fined by rookie umpire Klem, O’Rourke yelled, “You will never umpire another game in the Connecticut League.” Klem said, “All right, Mr. Manager. But I’ll umpire this one.” O’Rourke was also owner of the team.

9 Collier’s Weekly, March 31, 1951: 62. Klem states: “There were never more than four umpires on the New York State payroll at any time, but to complete the 1903 season 35 had to be hired. I was the only arbiter to start and finish the season.”

10 Collier’s Weekly, March 31, 1951: 64.

11 Ibid.

12 Collier’s Weekly, March, 1951: 64.

13 Ibid.

14 Collier’s Weekly, March, 1951: 65.

15 Although Klem praised Johnson for his support of umpires as American League president, he referred to him as a “screaming harridan” and criticized Johnson’s “domineering personality,” “arrogance,” and “domineering tactics.” See part four of “Umpire Bill Klem’s Own Story,” Collier’s Weekly, April 21, 1951: 73.

16 Ibid. “I liked Mr. Pulliam,” said Klem. In 1905, the American League made an aggressive campaign to sign Klem. League President Johnson and veteran AL umpires Tom Connolly, Jack Sheridan, and Silk O’Loughlin sent letters and telegrams to Klem encouraging him to sign with the American League. Klem ignored the correspondence. “I felt I had given (NL President) Mr. Pulliam a promise and waited to hear from him,” said Klem. Collier’s Weekly, March 31, 1951: 64-65.

17 David L. Porter, ed., Biographical Dictionary of American Sports: G-P (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1987), Klem entry, p. 820; Frank Fitzpatrick, “Klem, the Old Arbitrator, was Father of Umpiring,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 2, 1999.

18 In later describing the play that prompted his retirement, Klem was incorrect in the details. Here’s how Klem tells it: “A St. Louis man attempted to steal second. Billy Herman took the throw and put the ball on the runner. I called him out. The runner jumped up and protested. I walked away from the beefing player, saying to myself, ‘I’m almost certain Herman tagged him.’ Then it came to me and I almost wept. For the first time in all my career, I only ‘thought’ a man was tagged.” (Collier’s Weekly, April 25, 1951: 74).

On September 13, 1941, the Cardinals played the Dodgers in St. Louis and it was Klem’s last major league game. The play-by-play account, however, reveals that there were no attempted steals during the game. Klem called out one runner at second base during the game and it was not a St. Louis runner. When Brooklyn’s Lew Riggs attempted to stretch a single into a double, Cardinals shortstop Marty Marion “tagged” him and Klem called him out. This was likely the play that Klem was recalling a decade later that convinced him to finally retire. (Box score and play-by-play account for September 13, 1941 game between Cardinals and Dodgers from Retrosheet.org.) Actually, the game involving the possible “missed tag” was the last regular season major-league game Klem ever worked. Four years later, in 1945, he worked some spring training games despite being blind in one eye.

19 “Umpire Records,” MLB.com website.

20 “I am frequently called the inventor of the umpire’s chest protector. I am not. I merely resurrected it and basically followed the design originated by the first King of the Umpires, John Gaffney.” See “Diamond Rhubarbs,” part three of the Collier’s Weekly series, April 14. 1951: 31.

21 Ibid. “Another innovation—this one is mine—scorned by the American League is the system we use to work behind the catcher.”

22 Collier’s Weekly, March 31, 1951: 64. Further confirmation is Klem stating: “I have already explained how I invented the ‘fair’ and ‘foul’ semaphores.” (Collier’s Weekly, April 14, 1951: 31). Klem, not a modest man, proudly said that he was responsible for several umpiring advancements, proclaiming that the fair-foul signal was just “the first of many innovations in umpire technique” that he had introduced. These other claims include: “I had the distinction of being the first umpire to put a fan out of the ballpark.” Collier’s Weekly, April 7, 1951: 30. (Unlikely, in that the major-league rule giving the umpire the authority to eject a fan had been introduced back in 1882. Dennis Bingham and Thomas R. Heitz, “Rules and Scoring,” in Total Baseball (New York: HarperPerennial, 1993), 2280.

“Many of these innovations are mine, and all of them helped baseball grow from a county fair attraction to the great, beloved spectacle it is today.” Collier’s Weekly, April 14, 1951: 31.

In talking about the plate umpire’s signals for balls and strikes, Klem said: “I originated that system in 1906 when my voice went bad and I could no longer follow the custom of bellowing each decision. I (also) invented the standard ‘safe’ and ‘out’ signals used today by umpires.” Collier’s Weekly, April 14, 1951: 31.

Klem may have helped popularize the ball-strike signals, but he was not the first to employ them. Baseball historian Peter Morris states: “Bill Klem is sometimes credited with pioneering umpire signals. While I have found no evidence to support that contention, it does appear that Klem was among the first to give added emphasis to his signals.” Morris gives a detailed description of how the ball-strike signals developed in A Game of Inches: The Stories Behind the Innovations that Shaped Baseball (Ivan R. Dee, 2006), 385-391.

23 “It was not until 1911 that the second umpire was required by the rulebook,” states baseball historian Peter Morris, A Game of Inches, 373.

24 Bill Klem’s daily career umpiring log, Retrosheet.org. Working the plate when partnered with a rookie umpire was a common practice for other veteran umpires as well, such as O’Day, Billy Evans, and Tom Connolly.

Full Name

William Joseph Klem

Born

February 22, 1874 at Rochester, NY (US)

Died

September 16, 1951 at Miami, FL (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.