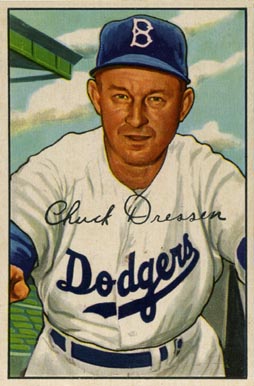

Chuck Dressen

While common wisdom dictates that baseball games are won with bats, balls, and gloves, Charlie Dressen believed until his dying breath that any game could be won with brains. Well, any game could be won with his brains. And it’s not hard to see why. Few field leaders had the percentages figured better than Dressen, he believed, and no one could match the sheer volume of retrievable information he accumulated during his five decades in baseball.

While common wisdom dictates that baseball games are won with bats, balls, and gloves, Charlie Dressen believed until his dying breath that any game could be won with brains. Well, any game could be won with his brains. And it’s not hard to see why. Few field leaders had the percentages figured better than Dressen, he believed, and no one could match the sheer volume of retrievable information he accumulated during his five decades in baseball.

Charles Walter Dressen was born on September 20, 1894, in Decatur, Illinois.1 He was the oldest of three children born to Phillip and Kate (Driscoll) Dressen.2 As a young man, he loved to race horses and for a time he considered becoming a jockey. His sharp mind and quick reflexes made him a standout in baseball and football, despite his small stature; he stood five feet five and weighed less than 150 pounds. While working as a switchman for the Wabash Railroad, he played for various football and baseball teams for whatever they were paying. The going rate to have him pitch was $7.50 a game. His arm wasn’t quite good enough to impress the scouts, but his hitting and fielding were.

The right-handed batting and throwing Dressen’s first Organized Baseball contract was a Minor League deal with the 1919 Moline (Illinois) Plowboys of the Class B Three-I League. He got in forty-two games with the Plowboys, playing mostly at second base. He returned to the Three-I League in 1920, this time as a member of the Peoria (Illinois) Tractors.

After the baseball season concluded Dressen returned to Decatur, where George Halas and Dutch Sternaman recruited him to play for the A.E. Staley Food Starch company football team. He appeared in four league games in 1920 for the Staleys, a precursor of the Chicago Bears. Returning to Peoria in 1921, Dressen, who had played almost exclusively in the outfield in 1920, was shifted to third base. Toward the end of the season, he moved up to the St. Paul Saints of the American Association.

Dressen was the Saints’ starting third baseman from 1922 through 1924, batting over .300 all three years. His breakout season was 1923, when he led the club with 71 extra-base hits, including 50 doubles and 12 home runs.

After the 1922 and 1923 seasons, Dressen picked up extra cash playing pro football. He joined the Racine (Wisconsin) Legion and played quarterback for the club in seven games in 1922, running for two touchdowns. Dressen played one game for Racine in 1923, but apparently determined his future was in baseball, not football, and quit the club.

Dressen’s instincts were correct. His average soared to .346 in 1924 and he led the Saints in virtually every offensive category, including RBIs with 151. That led the Cincinnati Reds to purchase his contract and send St. Paul a couple of Minor Leaguers to seal the deal.

Dressen made his big-league debut as a pinch-hitter on April 17, 1925, and had his first hit nine days later, against Wilbur Cooper of the Cubs. He saw action at second, third, and the outfield for the third-place Reds, batting .274 in seventy-six games. A month into the 1926 season, Dressen took over at third base. He batted .266 and led the National League in assists at third base.

Dressen had his finest big-league season in 1927, batting .292 and finishing among the league leaders in doubles, triples, and walks. But by 1929 his average had dipped to .244 and in 1930 he lost his starting job to young Tony Cuccinello. He split most of 1931 between the Minor League Baltimore Orioles and Minneapolis Millers. He knew he was nearing the end of the line; however, unlike most ballplayers, he was prepared.

In 1932 Dressen was essentially without a job. When he learned in June that the Nashville Volunteers of the Class A Southern Association were in need of a new manager, he borrowed train fare from a friend and made Vols owner Fay Murray an offer he couldn’t refuse. There were seventy-seven games left on the schedule—if Dressen failed to win more than half of the remaining contests, Murray wouldn’t owe him a dime.

On the final day of the season, Nashville’s record under Dressen stood at 38 and 38. Playing the Crackers in Atlanta, the Vols fell behind in the early innings. They rallied to win, so Dressen got paid. He also got a one-year deal to manage the club and play third base in 1933. It was as manager of the Vols that he earned a reputation for an encyclopedic knowledge of player tendencies and situational statistics.

In early September of 1933, Dressen left the Vols to play third base for the New York Giants, with whom Nashville had a working arrangement. The Giants third baseman, Johnny Vergez, had been stricken with appendicitis. Dressen played in sixteen games for the pennant-winning Giants, batting .222.

He was back managing Nashville in 1934, when in July, with the Reds twenty-nine games under .500, player-manager Bob O’Farrell was dealt to the Cubs. Dressen was offered the job. He quit his post at Nashville and took the managerial reins in Cincinnati. He didn’t do much better than O’Farrell, as the Reds finished in last place.

Dressen piloted Cincinnati to a sixth-place finish in 1935 and a fifth-place finish in 1936. In 1937 the Reds tumbled into the cellar again, and when Dressen demanded to know his status for 1938, he was let go with a month left in the season. Consequently, he returned to Nashville, now a Dodgers affiliate in ‘38, and guided the team to a second place finish. Larry MacPhail, former Reds general manager and now in a similar role in Brooklyn, added Dressen to Leo Durocher’s staff as a third-base coach for 1939.

The 1939 Dodgers were a ballclub on the rise. After a seventh-place finish in 1938, the 1939 team finished third, followed by a second-place finish in 1940. In 1941 the Dodgers outlasted the St. Louis Cardinals in a pennant race that went down to the wire. Durocher called the shots for this remarkable club, but rarely without input from Dressen. Although the Yankees defeated the Dodgers in the World Series, the news wasn’t all bad for Charlie. After the season he married the former Ruth Sinclair.

Branch Rickey, who replaced MacPhail as Brooklyn’s president after the 1942 season, apparently did not appreciate Dressen’s fondness for horse racing. When Charlie refused to swear off gambling, Rickey fired him in November of 1942. In July 1943, with Dressen staying away from the track, Rickey rehired him and he remained with the Dodgers through the 1946 season.

After returning from military duty, MacPhail came into Dressen’s life for a third time. He bought a piece of the Yankees and, in his dual role as general manager and president, immediately cast his eye on the Dodgers coaching staff. MacPhail lured Dressen and Red Corriden to the Bronx, where the team’s new manager, Bucky Harris, was trying to get the Yankees back on the pennant-winning track.

Dressen broke a cardinal rule of baseball, however, by signing his Yankees contract while still a Dodgers employee. That slip-up earned him a 30-day suspension and one-twelfth of his salary.

One of Dressen’s special talents was his ability to steal opponents’ signs. From his vantage point on the coaching lines he was often able to make out how many fingers the catcher was putting down, and then inconspicuously relay this information to the batter as the pitcher began his windup. This could be risky to the batter if the batterymates became suspicious, particularly in the days before batting helmets. Once when Joe DiMaggio was at the plate, Dressen flashed the sign for a curve. The pitch was a fastball up and in; only DiMaggio’s catlike reflexes enabled him to avoid a beaning. He cursed Charlie after the at bat and ignored his signs thereafter.

Besides manning the coaching box at third, Dressen doubled as pitching coach. He set down a few rules and schedules, and went over the hitters before each series, but did not offer much in the way of technical assistance. (Some pitchers thought he offered too much.) Dressen took an interest in some of the hitters, too, though there again his advice didn’t sit well with many of them.

The Yankees won the pennant and World Series in 1947. Charlie Dressen thus became the answer to a baseball trivia question: Who was the only man in uniform for the city’s three baseball teams—the Yankees, Dodgers and Giants—when they clinched a pennant?

The Bronx Bombers faltered in 1948, finishing behind the Indians and Red Sox. Dressen’s protector, Larry MacPhail, sold his share in the team, so it came as no surprise when Charlie was let go by general manager George Weiss, who never really considered him “Yankee material.” Harris was shown the door, too. The new hire was Casey Stengel, with Dressen grabbing the managing job Stengel left, with the Oakland Oaks of the Pacific Coast League. Dressen guided the Oaks to a second-place finish in 1949 and a PCL pennant in 1950.

That winter the call came from Brooklyn again. This time the Dodgers wanted Dressen to be their manager. He inherited one of the most talented rosters in National League history, one that included Gil Hodges, Jackie Robinson, Pee Wee Reese, Carl Furillo, Duke Snider, Roy Campanella, Don Newcombe, Preacher Roe, and Carl Erskine.

Dressen did much of his managing from the third-base coaching box with 1951 Dodgers. Under his guidance the team held a double-digit lead over the second-place Giants in mid-August. Then things began to tighten up. The Giants came roaring back and, under pressure, the Dodgers dropped six of their last ten to finish the regular season in a first-place tie. A best-of-three playoff ensued, with a coin flip to determine who would get the rubber game if necessary. The Dodgers won and Dressen opted to play the opener in Ebbets Field, giving the Giants the next two at the Polo Grounds.

After the Giants won Game One, behind Jim Hearn’s five-hitter, the Dodgers came back to win Game Two, 10–0. The deciding game remains perhaps the most famous ever played. Newcombe held the Giants in check for eight innings and the Dodgers were up 4–1 with three outs to go. The Giants scored a run against Newcombe and had two men on when Dressen called coach Clyde Sukeforth in the bullpen. Branca and Erskine were warming up. Sukeforth reported that Erskine had just bounced a curve. Despite the fact that the batter, Bobby Thomson, had homered off Branca in Game One, Dressen chose him to close out the Giants. The rest is history.

Dressen had better luck in 1952 and 1953. The Dodgers won the pennant both seasons. The ’52 team won ninety-six games—exactly the number Dressen predicted prior to the start of the campaign. The ’53 team won 105 games and finished thirteen games ahead of the second-place Milwaukee Braves. The only smudges on Dressen’s record of achievement in 1952 and 1953 were World Series losses to the Yankees—in seven games the first year and in six the next.

Dressen had been working on one-year contracts with the Dodgers. During the off-season, he and Ruth composed a letter to Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley explaining why he deserved a three-year deal. O’Malley’s response was that the Dodgers had probably paid more people for not managing than any other club in baseball, so it was one year or forget about it. When Dressen did not back down, O’Malley called a press conference to announce the hiring of Walter Alston as the team’s new skipper.

Brick Laws, owner of the Oakland Oaks, snapped up Dressen to manage his club in 1954. He led Oakland to a third-place finish and in 1955 was hired to replace his old boss Bucky Harris as skipper of the Washington Senators. The Nats lost 101 games in 1955 and 95 in 1957. Twenty games into the 1957 season, Dressen was relieved of his duties and replaced by Cookie Lavagetto.

In 1958 Dressen returned to the Dodgers for a third go-round, this time as a member of Alston’s coaching staff. He helped preside over the move to Los Angeles, which resulted in a surprising World Series championship in 1959. Hot off this success, Dressen was hired by the Braves as their manager for the 1960 season. Milwaukee boasted two of baseball’s most productive sluggers in Eddie Mathews and Hank Aaron, and an ageless pitching ace in Warren Spahn. But the supporting players who helped the Braves win pennants in 1957 and 1958 were fading, and the farm system had little to offer. Milwaukee finished second in 1960 under Charlie. In 1961, with the team out of the pennant race by September, he was replaced by Birdie Tebbetts.

Dressen stayed with the Braves as a Minor League manager, taking over the Toronto Maple Leafs in 1962. The Leafs missed the pennant by two and a half games—quite an improvement from 1961, when they were a sub-.500 ballclub. The Braves weren’t offering a big league job in 1963, so Dressen went back to the Dodgers a fourth time and agreed to scout for them.

That job lasted until mid-June, when Dressen got a call from the Detroit Tigers to replace Bob Scheffing. In their final 102 games Detroit went 55-47. In 1964, the Tigers went 85-77 and returned to the first division with a fourth-place finish.

During spring training in 1965, Dressen suffered a heart attack. Bob Swift took over the Tigers for forty-two games before Dressen felt well enough to return. Detroit finished fourth again. They got off to a 5-0 start in 1966, but a month into the season Dressen had a second heart attack. While recuperating he got a kidney infection and subsequently had a third, this time fatal, heart attack. He died on August 10, 1966.

Charlie Dressen’s overall record as a Major League manager with five teams was 1,008-973. He managed two pennant winners, played for a world champion with the 1933 Giants, and coached on World Series winners in 1947 with the Yankees and in 1959 with the Los Angeles Dodgers. As a player Charlie was active in seven big league seasons, was a regular for four years, and had a career batting mark of .272.

Although he was a nonstop talker and supreme egotist, Dressen was the flesh-and-blood epitome of a baseball lifer—single-minded, resilient, and always thinking three steps ahead.

Sources

Barra, Allen. Yogi Berra: Eternal Yankee. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2009.

Frommer, Harvey. Baseball’s Greatest Managers. New York: Franklin Watts, 1985.

Henrich, Tommy, with Bill Gilbert. Five O’Clock Lightning. New York: Birch Lane Press, 1992.

Rosenthal, Harold. Baseball’s Best Managers. New York: Bartholomew House, 1961.

Baseball Digest

Look

Sport

Sport Life Complete Baseball

Sports Illustrated

True Baseball Yearbook

Brooklyn Eagle

Detroit Free Press

New York Daily News

Notes

1 Dressen’s birth date is often mistakenly given as September 28, 1898. Throughout his baseball career, he was actually four years older than he claimed to be.

2 Dressen’s father, Phillip, had immigrated from Germany in 1882; his mother, the former Kate Driscoll, had immigrated from England in 1880. The family spelled the name “Dresen,” which is how Charles signed his World War I draft card.

Full Name

Charles Walter Dressen

Born

September 20, 1894 at Decatur, IL (USA)

Died

August 10, 1966 at Detroit, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.