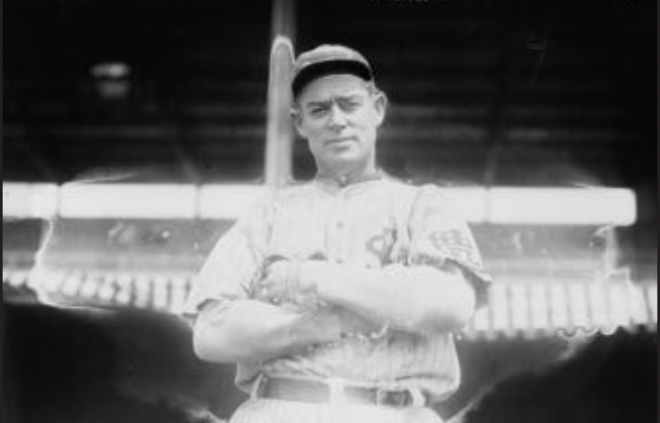

Ed Willett

A member of the three-time American League champions, Ed “Farmer” Willett was a fixture in the Detroit Tigers rotation from 1908 to 1913. During that six-year period, the 6-foot, 183-pound right-hander won at least 13 games in each season, topping out with a career-high 21 victories in 1909 when the Tigers captured their third consecutive pennant, and went a combined 95-72. A headstrong and free-spirited pitcher who lived on the inner half of the plate, Willett early in 1914 was one of the first established major leaguers to sign with the Federal League.

Robert Edgar Willett was born in Norfolk, Virginia, on March 7, 1884.1 He was one of nine children born to Robert Wilson Willett and Mary Elizabeth (Cox) Willett.2 Robert W. Willett descended from Scottish and English settlers, some of whom came to America in 1666. His mother was Elizabeth Adams, of the family of Samuel Adams.3 The senior Willett worked as a mechanic and farmer.4 Mary was a teacher and homemaker. She wrote short stories and was a student of literature. Her family, plantation owners, was originally English and settled in North Carolina and Virginia prior to the Revolution.5

Given his family’s background, Willett was fairly well-educated and well-rounded and held opinions on a wide range of topics. His rural roots earned him the nickname Farmer, and the military tradition of his Southern origin instilled in him a sense of pride and strong will. Both characteristics would serve later serve him well on the mound. Though he did not earn a college degree, Willett briefly attended a military academy in Virginia before pursuing a career in professional baseball.6

Willett began his professional baseball career in the Class-C Western Association. He pitched for the Wichita Jobbers in 1905 and 1906. He compiled a 10-5 record in 16 games in 1905 and a 12-17 record in 38 games in 1906. Although he had a losing record in 1906, he was regarded by many as the best pitcher in the Western Association.7

On August 9, 1906, Willett’s contract was purchased by the Detroit Tigers.8 He was originally scheduled to remain with the Jobbers through the end of the season but the Tigers, who were on their way to a sixth-place finish in the American League and in desperate need of pitching, asked the Wichita club to allow Willett to report before the conclusion of the Western Association season.9

On September 5, 1906, Willett made his major-league debut, against the Chicago White Sox at Bennett Park in Detroit. The 22-year-old rookie shook off a case of early nerves that resulted in a first-inning run and impressed the Tiger faithful by tossing a five-hit complete game in which he gave up only two runs.10 Unfortunately for Willett, White Sox left-hander Doc White was even better as he shut out the Tigers on two hits. Willett tossed two more complete games to close out his 1906 season but was the victim of poor run support. On September 14 he dropped a 6-0 decision to Addie Joss and the Cleveland Indians in which the Tigers managed only three hits.11 On October 6, the next-to-last day of the season, Willett lost his third consecutive start, a 4-2 setback to the St. Louis Browns. He finished the year 0-3 with a 3.96 ERA.

Willett joined the Tigers about the same time Ty Cobb was breaking in with the team. Cobb, a fellow Southerner, had few friends on the club and the right-handed rookie pitcher was the only Tiger willing to room with the Tigers center fielder. Cobb biographer Al Stump recounted the end to the roommates’ brief living arrangements:

“[T]he twenty-two-year-old Willett bunked with the Georgian at home and away until one day he announced that he was moving out. Willett admitted that he had been warned by certain Tigers to find other housing or “get hurt bad.” Cobb reportedly told Willett, ‘You are at a crossroads, Edgar. Those men just want to get at me through you. And they’ll make a whiskey head out of you, like them. If I was in your place I’d tell them to go to hell.’ But Willett, further unnerved by the gun Cobb carried with him on team travels, moved out of their small quarters in Detroit’s Brunswick Hotel.”12

Cobb never forgave Willett for moving out and socializing with the team’s anti-Cobb faction, who included such players as George Mullin, Ed Killian, and Matty McIntyre.13 In fact, in Cobb’s 1961 autobiography, My Life, he implied that Willett’s career had ended prematurely because the “sporty life” had caught up with him.14

Willett saw limited action with the Tigers in 1907. He appeared in just 10 games, six as a starter, and compiled a 1-5 record with a 3.70 ERA in 48⅔ innings pitched. He earned his first major-league victory on April 26 when he tossed a four-hitter to beat right-hander Harry Howell and the St. Browns, 3-1. The Tigers finished the year with a record of 92-58-3 and edged out the Philadelphia Athletics for the team’s first American League pennant. Not surprisingly, Willett did not pitch in the World Series as the Tigers succumbed to the Chicago Cubs in five games.15

Despite the inactivity, it was during this year that Willett established his reputation for not being afraid to pitch inside and stick up for his teammates.16 Throughout his career he had a propensity for hitting batters. He led the American League with 17 hit batsmen in 1912 and finished in the top 10 of league leaders (AL and Federal League) in this category for seven straight years from 1908 to 1914. His career total of 105 hit batsmen ranks 74th in major-league history.

The 1908 season started in a similar fashion for Willett. He made his first appearance of the season on Opening Day when he was called upon to mop up after veteran left-hander Ed Siever. Willett entered the game in the bottom of the fourth inning after Siever yielded 11 runs to the White Sox. While Willett gave up four unearned runs himself, the Detroit Free Press noted that he “finished the game in good style, stopping the Sox and holding them to four hits.”17 Despite the solid outing, Willett did not make his second appearance of the season until May 19. He was inserted into the starting rotation on May 31 and quickly established himself as a dependable and durable hurler. Exceptionally strong and powerfully built, Willett averaged 245 innings per year from 1908 to 1913. Tigers manager Hughie Jennings paid homage to Willett’s durability when he remarked, “Ed is always out there keeping the boys steady. He takes the ball whenever he’s told and never seems to tire.”18

Willett finished the 1908 season with a record of 15-8 and a 2.28 ERA as the Tigers roared to their second consecutive pennant. His breakout season notwithstanding, Jennings opted not to use Willett in the World Series in favor of Ed Summers, Wild Bill Donovan, and Mullin. For the second consecutive year, the Tigers were defeated by the Chicago Cubs in five games.

Soon after the World Series, Willett married Emma Jenereaux in a ceremony in Windsor, Ontario.19 The marriage was short-lived. Just over a year later, upon his return from Cuba, where the Tigers were playing in the Cuban-American Major League Clubs Series, Willett filed for divorce. Newspaper accounts suggested that it was “merely a case of disappointment from the time the knot was tied.”20 Mrs. Willett intimated that there was another woman in her husband’s life.21

Despite the marital discord, Willett enjoyed his best season in 1909. He pitched in a team-leading 41 games, 34 as a starter, and compiled a 21-10 record with a 2.34 ERA in 292⅔ innings pitched. His work on the mound was integral to the Tigers’ third straight American League crown.

Again Jennings choose not to start the 25-year-old righty in the World Series against the Pittsburgh Pirates, using Mullin and Donovan to start five of the seven games. In the other two games he went with Summers, a decision that most certainly was second-guessed after Summers allowed 13 runs in his two starts that spanned only 7⅓ innings while Willett tossed 7⅔ innings of solid relief in which he yielded only a single unearned run.

Willett made his first World Series appearance in Game Three, in relief of Summers. The right-handed knuckleballer had faced only six batters, given up five runs, and recorded only a single out before being lifted in favor of Willett. The Pirates added a sixth run in the second when Willett hit Tommy Leach in the hand and Fred Clarke in the knee to put runners on first and second with one out. Honus Wagner followed by hitting into a fielder’s choice that forced Clarke at second. With second baseman Dots Miller at the plate, Leach and Wagner attempted to execute a double steal. The play appeared to fail when Leach was caught in a rundown between third and home, but when Willett dropped the ball, Leach scored to increase Pittsburgh’s lead to 6-0.22 Willett gave up only three hits and held the Pirates scoreless over the next five innings as the Tigers lost, 8-6.

Two days later, in Game Five, Willett again came on in relief of Summers. Entering the game in the bottom of the eighth with a runner on first and the Tigers trailing 8-4, Willett retired pitcher Babe Adams on a pop fly to first, struck out third baseman Bobby Byrne, and got out of the inning when catcher George Gibson was caught trying to steal third.

With the Series tied 3-3, Jennings had to decide whether to start Willett or Game Two winner Donovan in Game Seven. The Tigers manager went with Donovan, who, true to his nickname, was wild. Donovan walked six and hit another batter before being relieved by Mullin in the fourth. Mullin, who was making his fourth appearance of the Series after complete-game efforts in games One, Four, and Six, was pitching on a single day of rest.23

The curious decision to not start Willett in the Series or even use him in relief in Game Seven stands as one of the oddest moves by a manager in the history of the fall classic.24 The following spring, the Reach Guide reflected on Jennings’ decision: “His next and greatest mistake was to take another chance with Summers in the fifth game, with Killian and [Ed] Willett ready and eager for the fray.”25

Willett had another strong season in 1910. He appeared in 37 games, 25 as a starter, and was 16-11with a team-leading 2.37 ERA. However, the Tigers’ run of three consecutive pennants came to an end as they finished third, 18 games behind the Philadelphia Athletics.

On October 25, 1910, Willett married Elizabeth White in a ceremony at the home of a friend in St. Louis.26 The couple honeymooned in Cuba, where the Tigers were once again in the Cuban-American Major League Clubs Series. Willett made three starts for the Tigers while on his honeymoon and finished the series with a 1-2 record and and a 0.67 ERA. The couple had two children, Robert Jr. and John.

Willett remained a regular in the Tigers rotation for the next three years. His ERA jumped more than a run, to 3.66, in 1911 when he recorded a 13-14 record. He bounced back in 1912 to record a team-leading 17 victories (he lost 15) with a 3.29 ERA. In 1913 he finished with a record of 13-14 and 3.09 ERA. With Mullin, Donovan, and Summers departed, the Tigers looked to Willett to provide a veteran presence to a younger rotation that included right-handers Jean Dubuc and Hooks Dauss. Unbeknownst to the organization, Willett had pitched his final game for the Tigers.

In January 1914 Willett signed a contract to play for the St. Louis Terriers of the Federal League. His defection to the Feds was a complete surprise to American League President Ban Johnson and Tigers owner Frank Navin. In fact, Willett had recently written to Navin apprising him of his determination to go to the Tigers’ training camp at Gulfport, Mississippi, early in order to get in shape in leisurely fashion. On his way down, Willett stopped off in St. Louis, where Terriers manager Three Finger Brown persuaded him to sign with the club. Johnson’s version of the signing painted Brown as a sinister villain in a skit Chicago sportswriter Matt Foley titled “Kidnapped in St. Louis.”27

Unlike many players whose stats improved by moving to the Federal League, Willett’s regressed. After starting the 1914 season with two complete-game victories, he endured a nine-game losing streak and finished the season with a career-worst 4-17 record and 4.27 ERA for the eighth-place Terriers. In 1915 Willett returned to the team in a relief role and compiled a 2-3 record as his ERA crept up to 4.61. He went a combined 6-20 during his two-year stay in St. Louis. On September 23, 1915, at age 31, he appeared in his last major-league game, a 10-2 Terriers victory in which he earned his second save of the season. Over his 10-year major-league career, Willett pitched in 274 games and finished with a record of 102-100 and a 3.08 ERA.

Over the course of his career, Willett improved his hitting and occasionally helped himself at the plate. From 1906 to 1910, the right-handed-batting Willett hit only .158 with 23 RBIs and a .408 OPS. From 1911 to 1915 he hit .231 with 5 home runs, 40 RBIs, and a dramatically improved .620 OPS. In 1911 he clubbed eight extra-base hits and batted .268, and in 1913 he hit .283 with 13 RBIs on 26 hits.28

Willett enjoyed his finest day at the plate on June 30, 1912, in a game against the White Sox at Navin Field. He went 3-for-4 with a pair of home runs and five RBIs. Willett was only the fifth major-league pitcher and second American League pitcher to hit two home runs in a game.29

Willett was also one of the best fielding pitchers in the American League, skilled at scooping up bunt attempts and comebackers.30 He consistently recorded a fielding percentage and a range factor per nine innings above the league average. Over his career, he had a fielding percentage of .949, which compared favorably to the .942 fielding percentage for all pitchers who pitched in the American and Federal leagues during the same years as Willett.31 Similarly, and perhaps more impressive, he had a range factor per nine innings (lgRF9) of 3.89 — .80 higher than the average of 3.09 for all pitchers.32 In simple terms, this means Willett had approximately 25% more defensive chances per nine innings than the average for all pitchers who pitched in the American and Federal leagues during the same years. This difference was largely attributed to his ability to get to balls that other pitchers could not.

After the Terriers released him, Willett continued to play in the minor leagues through 1919. He went 8-6 with the Memphis Chickasaws of the Southern Association in 1916. In 1917, with the New Orleans Pelicans of the Southern Association, he posted a record of 9-6. He then moved west to the Pacific Coast League, where he spent two seasons with the Salt Lake City Bees, going 2-4 and 1-3 in 1918 and 1919 respectively.

Willett worked a number of different jobs following his retirement, including operating a billiard hall and working as a carpenter. After being released by the Bees in 1919, he joined the Rexburg (Idaho) club of independent Snake River-Yellowstone League. In 1920 he led Rexburg to the league championship as player-manager.33 He began the 1921 season with the Blankenship team in the Pacific International League, pitching and playing the outfield and first base, before moving on to Victoria in British Columbia and eventually taking over as player-manager of the Ogden Gunners in the Northern Utah League.34

Willett later lived in Wellington, Kansas, where he managed an amateur baseball team. On May 10, 1934, he was found dead in his hotel in Wellington, the victim of a heart attack at the age of 50.35 He was buried in the Caldwell Cemetery in Caldwell, Kansas.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author relied on Retrosheet.org and Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Some sources list Cerro Gordo, Illinois, as Willett’s birthplace. Others list Norfolk, Virginia. Most US Census records identify Willett as being born in Virginia.

2 The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, “International Genealogical Index (IGI),” database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/2:1:MY68-2CF: accessed April 10, 2018), entry for Robert Edgar Willett; submitted by rdunagan70052 [identity withheld for privacy]; no source information is available.

3 John Quincy Adams and Samuel Adams were cousins.

4 Ted and Carole Miller, “Blanche Alphaola Stutevoss,” Nebraskana, 2005: 1162. https://usgennet.org/usa/ne/topic/resources/OLLibrary/Nebraskana/pages/nbka0260.htm.

5 Ibid.

6 Dan Holmes, “Willett Was Fine Pitcher, Fielder and Hitter for Tigers in Deadball Era,” https://detroitathletic.com/blog/2012/08/13/willett-was-fine-pitcher-fielder-hitter-for-tigers-in-deadball-era/, August 13, 2012.

7 “Willett Sold to Detroit: Will Report at End of the Season,” Wichita Daily Eagle, August 10, 1906: 6.

8 Ibid.

9 “Willett to Leave Soon: Will Report to Detroit This Coming Week,” Wichita Daily Eagle, August 26, 1906.

10 “He Looks Good: Willetts [sic] Pitches Splendid Game to Start His Big League Career,” Detroit Free Press, September 6, 1906: 9.

11 “Tigers at Cleveland Make an Event Break in the Double Bill,” Detroit Free Press, September 15, 1906: 9.

12 Al Stump, Cobb (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2004), 124.

13 Frank Russo, “Ed Willett,” findagrave.com/memorial/42505539.

14 Russo.

15 The Cubs beat the Tigers 4-0-1. Game One was a 3-3, 12-inning tie.

16 Holmes, “Willett Was Fine Pitcher, Fielder and Hitter for Tigers in Deadball Era.”

17 Joe Jackson, “Tigers Go Down to Defeat in the First Battle of the Season,” Detroit Free Press, April 15, 1908: 1.

18 Russo.

19 Ontario Marriages, 1869-1927, database with images, FamilySearch (familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:KSZX-61P: 11 March 2018), Robert Willett in entry for Edgar Willett and Emma Jenereaux, 17 Oct 1908; citing registration, Windsor, Essex, Ontario, Canada, Archives of Ontario, Toronto; FHL microfilm 1,871,866.

20 “Pitcher Willett Sues for Divorce,” Pittsburgh Press, October 29, 1909: 19.

21 “Wife to Fight Divorce Bill: Mrs. Edgar Willett, Detroit Hurler’s Spouse, to Contest Suit,” Indianapolis News, November 2, 1909: 10.

22 Dennis DeValeria and Jeanne Burke DeValeria, Honus Wagner: A Biography (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1995), 225.

23 Mullin started and lost Game One, shut out the Pirates in Game Four and started and lost Game Six.

24 Dan Holmes, “Willett Was Fine Pitcher, Fielder and Hitter for Tigers in Deadball Era.”

25 Dan Holmes, “Ed Killian,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/0356959b.

26 “’Farmer’ Willett Married,” Anthony (Kansas) Bulletin, November 4, 1910: 1.

27 Matt Foley, “Feds to Start Work on Plant Within 2 Weeks,” Chicago Inter-Ocean, January 21, 1914: 13.

28 Dan Holmes, “Willett Was Fine Pitcher, Fielder and Hitter for Tigers in Deadball Era.”

29 Keith Sutton, “Pitchers as Home Run Hitters,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, 1974, https://sabr.org/journal/article/pitchers-as-home-run-hitters/. Willett’s Tigers teammate Ed Summers was the first American League pitcher to hit two home runs in a game, on September 17, 1910. They were the only two home runs Summers hit in his career.

30 Dan Holmes, “Willett Was Fine Pitcher, Fielder and Hitter for Tigers in Deadball Era.”

31 The .942 fielding percentage (lgFld%) for all pitchers is the combined average fielding percentage of American League pitchers from 1906-1913 and Federal League pitchers from 1914 and 1915, the years Willett competed in each circuit.

32 The 3.09 range factor per nine innings (lgRF9) for all pitchers is the combined range factor per nine innings of American League pitchers from 1906 to 1913 and Federal League pitchers from 1914 and 1915, the years Willett competed in each circuit.

33 “Willett Assumes Management of Ogden Club Today: Big Leaguer Promises Fans Winning Club,” Ogden (Utah) Standard-Examiner, June 4, 1921: 6.

34 Ibid.

35 “Former Ogden Pilot Is Dead in Kansas: Ed Willett Gained Fame with Detroit; Served as Baseball Skipper,” Ogden Standard-Examiner, May 11, 1934: 9.

Full Name

Robert Edgar Willett

Born

March 7, 1884 at Norfolk, VA (USA)

Died

May 10, 1934 at Wellington, KS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.