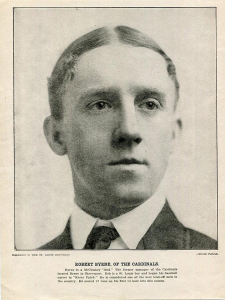

Bobby Byrne

Standing a tad under 5’8″ and weighing just 145 lbs., Bobby Byrne was a scrappy, pint-sized third baseman for the Pittsburgh Pirates towards the end of their reign as one of the National League’s top teams. “Byrne is always a dangerous man for the reason that at all times he is cool, nervy and smart,” wrote Alfred H. Spink, founder of The Sporting News, in 1910. Perhaps his actions in a game against Brooklyn on June 10, 1911, best illustrate the type of player he was: with Byrne at first and Fred Clarke at third, the two Pirates pulled off a double steal, with Byrne sneaking to third as Brooklyn catcher Bill Bergen argued the call at home with umpire Bill Klem. After Dots Miller walked, he and Byrne pulled off another double steal, giving the hustling leadoff hitter steals of second, third, and home in the same inning.

Standing a tad under 5’8″ and weighing just 145 lbs., Bobby Byrne was a scrappy, pint-sized third baseman for the Pittsburgh Pirates towards the end of their reign as one of the National League’s top teams. “Byrne is always a dangerous man for the reason that at all times he is cool, nervy and smart,” wrote Alfred H. Spink, founder of The Sporting News, in 1910. Perhaps his actions in a game against Brooklyn on June 10, 1911, best illustrate the type of player he was: with Byrne at first and Fred Clarke at third, the two Pirates pulled off a double steal, with Byrne sneaking to third as Brooklyn catcher Bill Bergen argued the call at home with umpire Bill Klem. After Dots Miller walked, he and Byrne pulled off another double steal, giving the hustling leadoff hitter steals of second, third, and home in the same inning.

The fifth and last child of John and Ellen Byrne (a sixth offspring apparently died either during childbirth or as an infant), Robert Matthew Byrne was born on New Year’s Eve, 1884, in the rough Kerry Patch section of St. Louis, a neighborhood that also produced “Scrappy Bill” Joyce, “Rowdy Jack” O’Connor, and Patsy Tebeau. Though Bobby was of Scottish ancestry, both of his parents were born in Ireland; John came to America at age seven in 1851, and Ellen immigrated at age 13 in 1864. As a youngster Bobby took to soccer first and was good enough to be selected to an All-St. Louis team. He played his first serious baseball with a local semipro club, the St. Louis Arcades, before embarking on a professional career as a shortstop with Fort Scott of the Missouri Valley League in 1904.

Making stops at Springfield (Western Association) in 1905 and Shreveport (Southern League) in 1906, Byrne finally reached the majors in 1907 with his hometown Cardinals. Moved to third base by manager John McCloskey, the right-handed hitter batted .256 in 149 games during his rookie year, but the following season he slumped to a disappointing .191. Byrne’s average stood at .214 when the Redbirds finally gave up on him on August 19, 1909, shipping him to Pittsburgh for cash and infielders Alan Storke and Jap Barbeau (so-nicknamed by a Columbus sportswriter for his swarthy appearance). On the new Pirate’s arrival, a Pittsburgh newspaper reported that he was “not a consistent hitter, [but] a great base runner . . . and a fine third baseman.” Byrne’s acquisition proved critical down the stretch; inserted into the leadoff spot, he compiled an on-base percentage of .387 (well above his career mark of .324) and made just two errors in 46 games as the Pirates captured their first pennant in six years.

During the 1909 World Series Byrne became involved in the biggest controversy of his career. After being hit in the shoulder by a pitch to lead off Game Seven, he reached second on a sacrifice but was thrown out trying to steal third. “I broke my ankle sliding into George Moriarty at third base and spiked the Tiger third sacker so badly that eight stitches were required to close a gash in his knee,” Byrne recalled years later. “It all happened in the first inning and probably was the only time in Series history that the regular third sackers of the rival clubs were carried off the field on stretchers.” (Byrne’s recollection wasn’t quite accurate; while he did indeed have to be carried off the field by teammates, Moriarty stayed in the game long enough to double in the second inning before giving way to a pinch runner.) Contemporary coverage of the incident wasn’t kind to the Pirate cornerman. “Byrne and Moriarty were injured when Bobby made a needless attempt to steal third in a game in which Wild Bill Donovan, the Detroit pitcher, showed nothing,” wrote one reporter. The Pirates won the game without Byrne, who received a big ovation when he showed up on crutches for the next day’s victory celebration at Forbes Field.

Though the defending World Champions slumped to third place in 1910, Byrne showed that he was fully recovered from his injury by putting together his greatest season, posting career highs in batting average (.296), runs (101), and stolen bases (36). Feasting on pitchers like never before, he led the NL in doubles (43) and tied teammate Honus Wagner for the lead in hits (178), an accomplishment he considered his greatest as a ballplayer. “That was quite a feat in those days,” he boasted, “especially when you consider that we did not have a ‘shiny rock’ to hit against every time we came to the plate. The ball was usually well discolored.” Byrne also might have bragged about a couple more of his 1910 achievements: on June 18 he made a dozen assists in a single game, a record for third basemen that still stands; and on August 25, in a game at Brooklyn, he doubled, stole third, and then stole home (the Pirates held on for a 4-3 victory), becoming the first NL player of the 20th century to steal home in an extra-inning game.

Despite going five-for-five and collecting five RBIs in a 14-0 pasting of the Reds on Opening Day 1911, Byrne batted just .259 for the season, though he did hit a career-high 17 triples. In 1912 he bounced back to hit .288 with 31 doubles, 11 triples, and a career-high three home runs. During the off-season, a few days after Thanksgiving, Byrne was driving near his home when his car ran into a telegraph pole. Accounts of the accident called his survival “a miracle.” Bobby thought he had escaped with merely a few scratches to his head and right arm, but the next week he began to experience a “jerking pain” on his right side. His doctors immediately confined him to bed, his back heavily wrapped in gauze to prevent further injury. Not long after he recovered from that brush with death, his mortality was tested a second time when he was struck behind the left ear by a Smoky Joe Wood fastball in a March exhibition game in Hot Springs, Arkansas. Knocked unconscious, Bobby remained in serious condition overnight but was back in action just one week later.

Though Byrne batted .270 in 113 games for Pittsburgh in 1913, reporters speculated that the lingering effects of his beaning were a factor when the Pirates traded him and pitcher Howie Camnitz to Philadelphia in August for outfielder Cozy Dolan and cash. Moving to second base in 1914 to allow Hans Lobert to remain at third, Byrne batted .272 in what turned out to be his last full season as a regular. The following year new Phillies manager Pat Moran shifted him back to third base, but the 30-year-old veteran broke his hand and was replaced by Milt Stock. Though he made just one pinch-hit appearance in that year’s World Series, Bobby told reporters afterwards that the Phillies “were not outplayed. I tell you we were outlucked, that’s all.” The next two years Byrne played in a combined 61 games for the Phillies. In September 1917 the White Sox picked him up for the waiver fee but went on to their World Series championship without him—Bobby batted just once for Chicago.

His playing days over at age 32, Byrne spent three years away from the game before becoming a minor-league manager in 1921. After stints at Miami (Oklahoma) and Saginaw, he returned to St. Louis at the age of 37, working first in several city positions and later for the US government and the Scullin Steel Company. Bobby also owned a bowling alley and once tossed 19 consecutive strikes, including a 300 game. He and his wife, Laura, had two sons, Bobby Jr. and Bernie, both of whom played minor-league baseball and became well-known fighter pilots during World War II. After Laura passed away in 1945, Bobby spent much of his time playing golf. In his later years, his prized possession was a certificate stating that Robert M. Byrne of St. Louis shot a 74 at the Lakeside Golf Club in Missouri—at the age of 74. “I find that golf keeps me in physical condition and I expect to continue in the game as long as I can swing a club and get enjoyment out of the sport,” he said at age 77.

Bobby Byrne died on his 80th birthday, December 31, 1964, at the Caley Nursing Home in Wayne, Pennsylvania, having succumbed to cancer of the liver and stomach. He was buried in Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis.

Note: A slightly different version of this biography appeared in Tom Simon, ed., Deadball Stars of the National League (Washington, D.C.: Brassey’s, Inc., 2004).

Sources

For this biography, the author used a number of contemporary sources, especially those found in the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Full Name

Robert Matthew Byrne

Born

December 31, 1884 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

Died

December 31, 1964 at Wayne, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.