Earl Moore

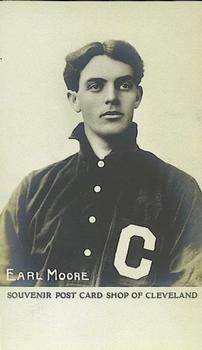

Nearly forgotten today amid the pantheon of great Deadball Era hurlers, Earl “Crossfire” Moore–so nicknamed for his unorthodox method of shooting a sidearm pitch from the very end of the rubber–ranked as one of the American League’s most promising young players during the first five years of its existence. Six feet tall, square-jawed, and with his cap pushed low over his eyes, Moore cut a striking figure on the mound, and he answered to an assortment of nicknames. When he racked up 79 victories by the age of 28–at times out-dueling Cy Young, Rube Waddell, Jack Chesbro, Chief Bender, and Eddie Plank–Earl appeared poised for greatness. But a drive through the box on an afternoon late in 1905 tore apart Moore’s left foot. Though the injury so debilitated him that he managed only six big-league victories over the next three seasons, it would not be the end for the self-proclaimed “Steam Engine in Boots.” After regaining his form in the minors, Earl became an 18- and 22-game winner for the Philadelphia Phillies staff in 1909 and 1910, respectively, before tapering off and finishing with the Federal League in 1914.

Nearly forgotten today amid the pantheon of great Deadball Era hurlers, Earl “Crossfire” Moore–so nicknamed for his unorthodox method of shooting a sidearm pitch from the very end of the rubber–ranked as one of the American League’s most promising young players during the first five years of its existence. Six feet tall, square-jawed, and with his cap pushed low over his eyes, Moore cut a striking figure on the mound, and he answered to an assortment of nicknames. When he racked up 79 victories by the age of 28–at times out-dueling Cy Young, Rube Waddell, Jack Chesbro, Chief Bender, and Eddie Plank–Earl appeared poised for greatness. But a drive through the box on an afternoon late in 1905 tore apart Moore’s left foot. Though the injury so debilitated him that he managed only six big-league victories over the next three seasons, it would not be the end for the self-proclaimed “Steam Engine in Boots.” After regaining his form in the minors, Earl became an 18- and 22-game winner for the Philadelphia Phillies staff in 1909 and 1910, respectively, before tapering off and finishing with the Federal League in 1914.

Most sources state that Earl Alonzo Moore was born in Pickerington, Ohio, on July 29, 1879 or 1878, but official birth records for Violet Township in Ohio’s Fairfield County indicate that the future major-leaguer actually began life on July 29, 1877, under the name of Alonzo Moore. One of 14 children of Reason G. and Martha Ann (Claybaugh) Moore, Earl was called both Lonzo and Lon growing up. The phonetics of the name Lon Moore gave rise to one of Earl’s first nicknames, Lon Mower, an appropriate sobriquet for a teenager who once stepped out of the crowd at a game in nearby Dayton to strike out 17 as the substitute for an injured pitcher. Later, he drew the attention of professional scouts playing semi-pro baseball at Bushnell Park in Columbus. Now going by Earl, Moore earned a spot with Dayton of the Inter-State League in 1899. The next season, making $85 a month, he overwhelmed hitters with his exceptional velocity and registered a 24-11 record (including a no-hitter) to help lead the team to a league title. His rise perfectly coincided with the formation of the American League in 1901, and the newly born Cleveland club snapped up the local prodigy for $1,000.

Moore started the second game in Cleveland AL history–a 7-3 loss at Chicago. After his home debut–a 6-3 victory over Milwaukee–the Cleveland Plain Dealer remarked that “he showed wonderful speed–almost up to the quality possessed by Cy Young in his best days, and fairly good control.” The Ohioan often relied on his fast ball against opponents, but he mixed in some “speedy benders,” too. Perhaps most aggravating to hitters was Moore’s signature “crossfire” pitching technique. In this unusual delivery, Moore cleverly toed the side edges of the rubber and, augmenting his wide mound position with a sidearm throwing motion, hurled pitches plateward at puzzling angles. Earl lamented his peers’ reluctance to try the method: “They rely on curves and changes of pace. Both are essential to success, but how much better they might succeed if they would only change from one side of the pitcher’s plate to the other. That is what constitutes the crossfire, in addition to the ability to stand with one foot on the extreme corner of the plate and step out and deliver the ball at the same time.”

In just his fourth outing, the 23-year-old soared to prominence by spinning the American League’s first-ever nine-inning no-hitter on May 9 against the Chicago White Sox, though he lost both the no-hitter and the game in the tenth frame. Moore overcame other setbacks in 1901–his father once angrily refused to contact him for two weeks after an 11-5 embarrassment to Philadelphia on July 30, author Franklin A. Lewis recalled–and fashioned a solid rookie season. Despite poor control (107 walks, 12 wild pitches), he went 16-14, fired four shutouts, and even vanquished Cy Young, 2-1, on July 19. Not surprisingly, considering his age and burgeoning reputation as an overpowering pitcher, Earl let the success go to his head–though he did so in typically endearing fashion. “Moore carries the title of ‘Steam Engine in Boots,’” noted the Washington Post, “and after his name in the hotel registers always appears the letters ‘S.E.I.B.’”

The cockiness may have been justified, given the amount of attention paid him by National League clubs. Cincinnati and New York took turns trying to pry the talented fireballer loose from Cleveland in 1901 and 1902. So certain did Earl’s defection to the NL seem in late July of 1902 that The Sporting News felt compelled to print a front-page subhead declaring, “Moore Has Not Jumped.”

On the diamond Moore overcame a spring-training bout with pleurisy to produce a mixed-bag of a season in 1902. He finished in the top ten in wins (17), ERA (2.95), games (36), innings (293), strikeouts (84), and shutouts (4), but continued to be plagued by wildness, leading the league in walks (101) and finishing fifth in losses (18). Life was bursting at the seams for the young ballplayer that year. On July 10 he wed Cleveland school teacher Blanche G. Patno, a marriage that would last 53 years. During the off-season, Moore stayed in the area and resided a short distance from League Park. He and Blues third baseman Bill Bradley became fierce rivals on the bowling alleys and billiard tables of the Forest City. “Both come downtown every afternoon and settle their disputes in bowling and pool,” wrote the Cleveland Leader. “Moore is an excellent bowler, and when he defeated Bradley three times, the third baseman suggested a pool match. Then Bradley had his revenge. Moore would not call quits until Bradley had won five games. Moore is an excellent pool player himself and was deeply chagrined at his defeat.” So enamored of the lanes did Moore become that he eventually managed a bowling alley. But he soon gave it up, calling the work “too strenuous for me.”

By comparison, throwing a baseball seemed easy for Earl in 1903. Adding 20 pounds to his frame (bringing him close to 200) and a $3,000 salary to his wallet, he enjoyed his greatest season in the American League, going 20-8 with a league-leading 1.74 ERA. He placed in the top ten of nearly every major pitching category, though at the outset, after a terrible 1-4 start, it appeared the year might be a disaster. Employing his scythe-like delivery, Earl captured 18 of his next 23 decisions–including 11 out of 12 from mid-July until the end of August. He beat every club in the circuit at least twice. He completed all 27 of his starts, and in 22 of those, allowed eight hits or fewer. His sub-2.00 ERA easily outpaced runner-up Cy Young’s by a third of a run and he notched wins over future Hall of Famers Jack Chesbro (twice), Eddie Plank and Chief Bender.

Moore’s skein would have been even more impressive, except that twice within a month the right-hander absorbed line drives off his pitching arm–one of them from the bat of teammate Charlie Hickman on July 24, while throwing batting practice. The damage to Earl’s arm caused him to miss the final month of the season, a bad omen for Crossfire.

Shrugging off a mediocre 1904 season–marred by rheumatism and a sliding injury–Earl broke to an excellent 13-7 start in 1905 and helped propel Cleveland into first place by late July. Then Moore’s career came instantly crashing down. In a game against the Highlanders at New York on August 1, a line drive ricocheted off the Steam Engine’s foot, damaging muscles and ligaments. The severity of the injury apparently was not recognized right away, because he finished the contest and continued to take his regular turn in the rotation until early September, possibly hurting the foot further. Clearly, Earl was not right during the final two months of the season: he was regularly shelled and went 2-8 the rest of the way.

As the 1906 season drew near, the dire nature of Moore’s injury became public. The renowned sports chiropractor, Bonesetter Reese, issued a statement from Youngstown, saying, “…pitcher Earl Moore will be of no use to the Cleveland Americans this year. The muscles of Moore’s left foot … have been torn loose, allowing the instep bone to drop down and making the pitcher flat-footed.” Earl and his Cleveland physicians disputed Reese’s claim and predicted a return to the hill in 8 to 10 weeks. But it proved to be wishful thinking and Reese’s prognosis was right on: the Naps hurler saw action in just five games for the year.

Not yet 30 years old, the right-hander’s career slid off the major league map. Struggling to mend his foot and regain form early in 1907, Moore was dealt to the New York Highlanders for Frank Delahanty and Walter Clarkson. The fresh start in Gotham failed to resurrect Earl: he finished the campaign at just 3-7 in 15 games. Finally, a minor league stint with Jersey City of the Eastern League beginning in August 1907 turned out to be just the right elixir. He went 13-12 for the Skeeters in 1908 and performed so encouragingly that the Philadelphia Phillies acquired him at the end of that season.

Moore astounded major league baseball in 1909 with an amazing comeback. Still using his rapid crossfire delivery, he became the ace of the Phillies staff and quickly ascended to the top echelon of National League hurlers. Despite persistent control problems–his 108 walks led the N.L.–Earl went 18-12 with a 2.10 ERA for a 74-79 team that finished in the second division. Known variously in the Philadelphia press as Big Earl, Big Moose, and Big Ebbie, Moore made it all the way back to the big time on August 19 by defeating Christy Mathewson, 1-0, at the National League Park. He followed it up with an electrifying 1910 campaign, pacing the league in shutouts (6) and strikeouts (185), and finishing third in wins (22). Phillies catcher-manager Red Dooin used Moore wisely, yanking him at the first sign that his pitches were not finding the plate (he lasted just one inning in a loss to the Cubs on September 16). Other times, Dooin permitted him to go the distance and even well into extra innings when Earl found a groove. Like fellow workhorses Mathewson and Three Finger Brown, he also received occasional relief assignments.

Future Hall of Fame umpire Bill Klem marveled at Moore’s mound mastery: “…I believe that Earl Moore, of the Phillies, has more stuff on his ball than any other pitcher I worked behind during the summer,” he said in January 1911. “Really, I never saw a more deceptive ball to judge than Moore’s cross-fire. It comes up to you at a peculiar angle, and if it’s half as hard to hit as it is for an umpire to judge, then I can easily understand why the batters don’t fatten their averages when Moore is working. His speed is tremendous, and his curves fast breaking. There are a lot of great pitchers in the National League, but Moore is the one best bet to me.”

Even when he was not on the hill, Earl could be tough on opponents. While coaching first base one April afternoon against New York in 1911, he drew the rage of John McGraw when, at the conclusion of an umpire dispute, he called the Giants manager a “wife murderer.” (In 1899 McGraw’s first wife had died tragically at age 22 of a burst appendix.) Already irked that Moore had shut out his Giants twice that season, McGraw grabbed a bat and went after him. Before McGraw could get to the Big Moose, however, the Philadelphia police broke up the skirmish.

Moore’s pitching renaissance turned out to be short-lived. En route to a disappointing 15-19 record in 1911, he began to fall out of favor with Philadelphia management due to his wildness on the mound–and off it, too. Reports ran rampant that he regularly broke team rules, failed to stay in condition, and did not give his best on the mound. The Phillies tried to peddle him to various National League clubs–Chicago, Brooklyn, New York, and Pittsburgh showed interest–but to no avail. They kept him for 1912, and he was injured by a hit ball yet again, this time breaking his finger. The Phillies finally unloaded him to the Cubs in 1913, and Earl’s major league career concluded in 1914 when, at long last, he jumped to an outlaw team and league, the Buffalo Federals. He went 11-15 with a horrendous 4.30 ERA to close out his topsy-turvy ride in the big leagues at 163-154.

Following his playing days, Moore remained close to the game of baseball (records show that both he and his wife Blanche had a season pass to the Indians for 1933). He occasionally participated in Indians old-timer’s games and frequently indulged his love of golf. Professionally, he held jobs selling both oil and real estate. Earl retired to his native Pickerington, the “Violet Capital of Ohio,” and became identified later in life primarily as the man who threw the first American League no-hitter. (This distinction, however, was taken away from Moore in 1991 by MLB’s rules committee, which ruled that only a complete hitless game of nine innings or more counts as a no-hitter.) As Moore entered his twilight years, a youngster named Gary Taylor–now a member of the Pickerington Historical Society–delivered the Columbus, Ohio newspaper to the aging ex-ballplayer’s residence. “I remember going to him and asking him how to grip the ball to throw a curve,” he said. “We sat on his front porch swing and talked a lot about how to pitch. He was very kind to me. He was always very accommodating to the kids in Pickerington.”

Appropriately, when Earl Moore died of complications from heart disease at age 84 on November 28, 1961, in Columbus, Ohio, the death certificate listed his business or industry in life as “Base Ball.” Under the heading “Usual Occupation,” he was identified simply as “Pitcher.” Earl is buried beside his wife Blanche at Glen Rest Memorial Estate in Reynoldsburg, Ohio.

Note

This biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

For this biography, the author used a number of contemporary sources, especially those found in the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Chicago Tribune

New York Times

Washington Post

The Sporting News (1901-1905)

Earl Moore File. National Baseball Library, Cooperstown, New York.

Earl Moore Collection. Pickerington-Violet Township Historical Society, Pickerington, Ohio.

John Phillips. Who Was Who in Cleveland Baseball in 1901-1910. Capital Publishing Co., 1989.

Full Name

Alonzo Earl Moore

Born

July 29, 1877 at Pickerington, OH (USA)

Died

November 28, 1961 at Columbus, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.