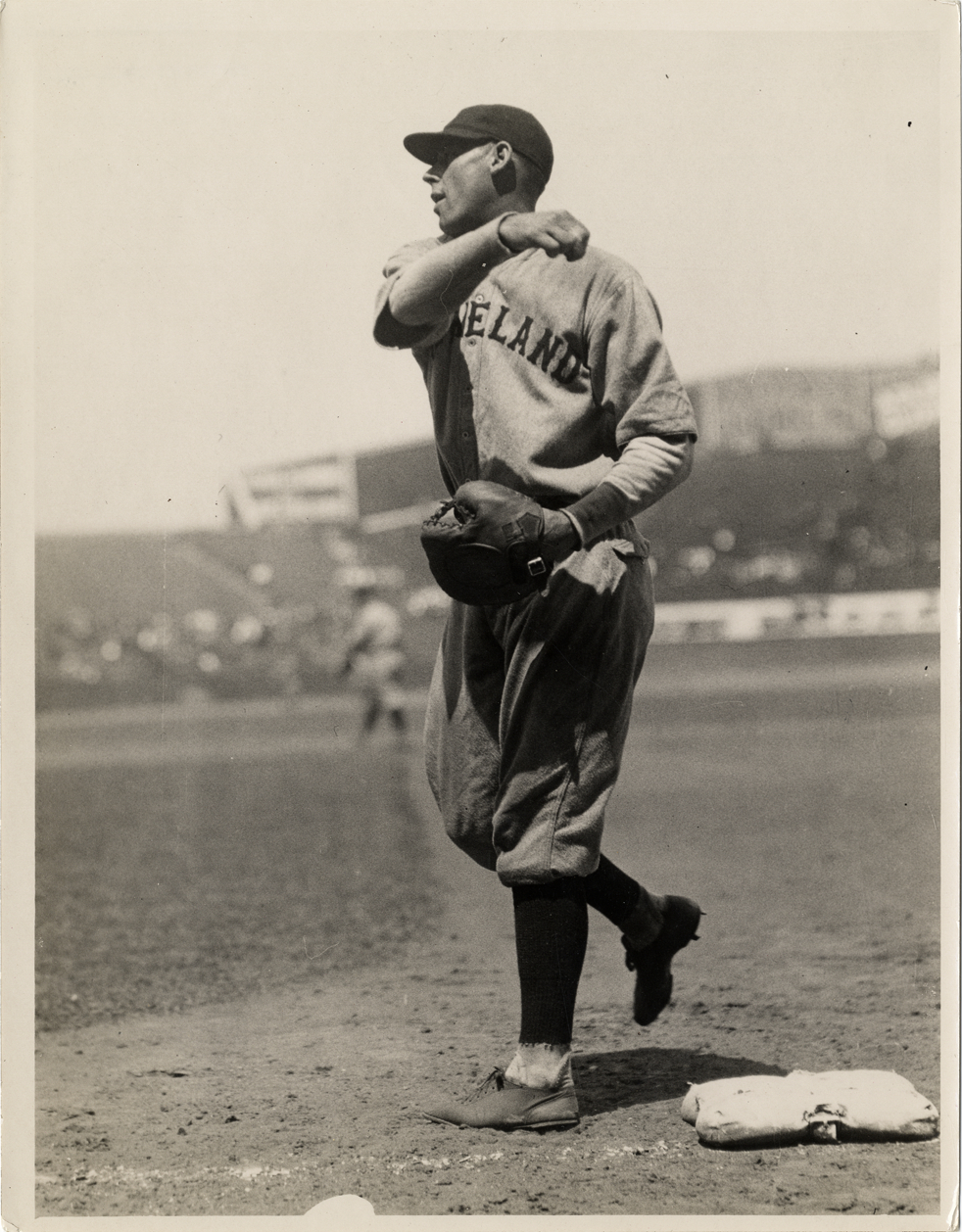

Frank Brower

On August 7, 1923, the Washington Senators sent rookie hurler Monroe Mitchell to the hill versus Cleveland. Mitchell was coming off a five-hit shutout of the Browns which had earned him his first major league victory. Against the Tribe, he lost his shutout immediately when Charlie Jamieson led off with a triple and scored on a Homer Summa single. Mitchell retired the next three hitters. In the second inning, Rube Lutzke led off with a single followed by another from Frank Brower. About 15 minutes later, Lutzke singled again, as did Brower off reliever Skipper Friday. The floodgates had opened. Cleveland had a 9-1 lead after two innings.

On August 7, 1923, the Washington Senators sent rookie hurler Monroe Mitchell to the hill versus Cleveland. Mitchell was coming off a five-hit shutout of the Browns which had earned him his first major league victory. Against the Tribe, he lost his shutout immediately when Charlie Jamieson led off with a triple and scored on a Homer Summa single. Mitchell retired the next three hitters. In the second inning, Rube Lutzke led off with a single followed by another from Frank Brower. About 15 minutes later, Lutzke singled again, as did Brower off reliever Skipper Friday. The floodgates had opened. Cleveland had a 9-1 lead after two innings.

The Tribe onslaught continued as they piled up 26 hits against three pitchers; Squire Potter came on in the seventh for his only major league appearance. Brower ended the game with six hits in as many at-bats. He had five singles and a double, scored three times, and had three RBIs. He stole a base in the ninth inning with his team up 21-2. The unwritten rules of baseball take a dim view of plays like that, but Brower may have been trying to give himself up like Lutzke and George Uhle had in previous innings. The Senator’s catcher dropped the pitch and Brower was credited with a stolen base. He scored to make the game 22-2. The Senators and Mitchell got a bit of revenge on August 24 when they won 20-8 and Mitchell pitched the last three innings in relief, which in modern times would have earned a save.1

Brower’s six hits in a nine-inning game tied the American League record; Wilbert Robinson had set the National League mark with seven. Brower became the sixth American Leaguer to make six hits in regulation. Since that day, 33 other AL batters have duplicated the feat. Tribe infielder Johnny Burnett holds the major-league record overall, with nine hits in an extra-inning game, against the Philadelphia A’s in 1932.

The Brower family had been in Virginia for many generations. Charles F. Brower was born into a farming family and went on to become a physician. In 1886, he wed Sarah F. Sanders in Prince William County, Virginia, which is just west of the nation’s capital. Frank Willard Brower was born March 26,1893, in the county near the small town of Cartharpin. He was the third of five children. The children attended school in nearby Manassas and Frank graduated from the high school before going on to two more years of school at Washington & Lee University in Lexington, Virginia. He enrolled with a reputation as a fine athlete and played baseball in 1913 and 1914 for the university.

Growing up, he earned the nickname “Tuckie” (also spelled as “Tuckey”) from his family. The origin of this name is unknown. The nickname “Turkey” started to appear when he played for the Washington Senators. His daughter, Ann, suggested “a Northern sportswriter whose ear was not attuned to the soft Southern syllables of his Manassas friends transcribed ‘Tuckey’ as ‘Turkey.’”2 When he joined Cleveland, some scribes lengthened the nickname to “Turkeyfoot,” a nickname that reappeared in some of his obituaries. Writer Scott Ostler picked up on the nickname in 1988 and suggested it identified a physical defect.3The family took umbrage with that depiction.4

Standing 6-foot-2 and weighing 180 pounds, Brower made an impression physically. He was not fleet-footed, but was agile enough to play second base when he was in his 30s. Brower was a right-handed thrower who batted left. In the summer of 1913 he went south to join the Miami Seminoles, a mix of semi-pro and college players, after being recommended by a Miami relative, A.B. Sanders. Miami opened their season with a series of games against Key West and Ft. Lauderdale. In his first eleven games, Brower batted .541 and his pitching was superb.

A group of cities formed the East Coast League and the season opened July 24 with Miami hosting Ft. Myers. “Brower for the Seminoles had everything: He was invincible, indomitable, indubitable and invulnerable … (the opponent) was like putty in his hands.”5 The Seminoles won their first five games, but were eventually caught by the Ft. Lauderdale squad and finished in second place. Brower stayed hot the entire season. The Miami News credited him with a .512 batting average in late August.6

When Miller Huggins and his St. Louis Cardinals trained in St. Augustine, Florida, in the spring of 1914, Brower asked for a tryout and Huggins liked what he saw from him as a pitcher. When the Cardinals broke camp in late March, Brower traveled north with the team. He never saw action with the Cardinals and was optioned to Scranton in the Class B New York State League. On June 8, he authored a five-hit shutout against Binghamton. In late June, the Miners changed managers and Bill Coughlin cleaned house. Brower was returned to the Cardinals, who in turn returned him to the NYSL on July 17 with the Utica Utes.

Manager Mike O’Neill installed Brower in the outfield when he was not pitching. The Utes were below .500 when he joined them, but they finished at 77-55 and in third place. He played 49 games that season and batted .252. On the mound, he tossed 88 2/3 innings, plus an exhibition game with the St. Louis Browns that he won, 5-3. Opponents batted .220 against him.7 Based upon entries in the Philadelphia Inquirer, he was 1-1 with Scranton and 5-2 with the Utes.

Brower was not a scientific batter in the early years. He strode to the plate looking to hit the ball as hard and far as he could. His 1914 statistics show him with 29 strikeouts and two walks in 155 at bats, a strikeout rate of 18.7%, which is common now, but a complete outlier in 1914. Following the season, the Phillies paid $1,000 for his rights, but returned him to Utica in March.

In 1915, Ed McDonough took over as manager of Utica. Brower opened the season as both outfielder and pitcher, but when Charles Kroy joined the team, Brower seldom saw time anywhere but on the mound. The Utes finished in second place behind Binghamton, while Brower batted .303 in 46 games and had a 13-5 record. Veteran Amby McConnell took over in 1916 and installed Brower at first base. He hit .292, second on the team behind McConnell’s .351, and Utica finished five games under .500.

In 1917, McConnell returned and Brower was slated to be first baseman again. He was pressed into mound service on June 1 in a bizarre game against Binghamton. Utica scored 10 runs in the first, but Binghamton came back with nine in the bottom of the inning. After three pitchers failed, Brower was brought in. He pitched until the fourth when the game was called on account of darkness. 8The franchise withdrew from the league at the start of the second half, with Brower playing 49 games and hitting .263.

Brower was one of four Utica players who reportedly signed with Portland of the Eastern League, but he did not report. He took a job in the Virginia shipyards instead. In January of 1918, he enlisted in the Navy as an ensign and served 361 days before being mustered out.

The 1919 Reading Coal Barons in the International League were headed for the cellar when manager Charles Dooin was replaced by Pop Kelchner in early August. Kelchner brought in new talent, including Brower, who arrived with a black bat and started hitting like Joe Jackson. In 47 games, he hit .317. The team changed its mascot to the Marines for 1920 and hired John Hummel as manager. Brower returned at first base along with his powerful teammate, catcher Mike Konnick. The pair led the league with 22 home runs apiece. Brower hit .388 before being sold to the Senators, while Konnick batted .336.

Brower made his major-league debut on August 14 against New York. He played right field and went 2-for-4 with an RBI in the 3-2 loss. He took over the right field job for the remainder of August. In September, he played first base, left field, and even a game at third. He ended the season on a seven-game hitting streak that raised his average from .280 to .311. More importantly, he became much more selective at the plate. Over his major-league career, he would walk twice as often as he struck out.

Following the regular season, he joined Joe Judge’s All-Stars and took on a Negro League contingent calling themselves the Brooklyn Giants. This was Brower’s second matchup with a Negro League team. While with Utica, the Utes had been handled roughly by a team called the Havana Red Sox. Judge’s team fared better as all four games were decided by 1 or 2 runs. Frank Baker and Sam Rice hit homers in the first game for a 2-1 win by Judge’s team. Brower had three hits in a Game 3 loss and then pitched four scoreless innings in relief in Game 4.

With Joe Judge at first base, Brower was marked for the outfield as a Washington reserve for 1921. Clyde Milan and Sam Rice were returning and veteran Duffy Lewis was added. Lewis was over-the-hill and batted a mere .186, which opened the door for Brower in May. Inserted into the lineup on May 6, he went on a hitting tear and was batting .378 on May 25. His hitting cooled and when Bing Miller replaced him in late June, he had dropped to .262. He closed out the year at .261.

In 1922, manager Clyde Milan benched himself in favor of Goose Goslin. Sam Rice patrolled center and Brower took over in right field after 10 games. He exploded at the plate and was hitting .355 on April 29. He cooled off and stayed around the .290 range most of the summer. He launched two solo homers off Waite Hoyt on August 30. In total, Brower played 139 games, batted .293 and launched nine homers. The Senators then swapped him to the Indians for 3B/OF Joe Evans in January.

The Indians planned on Brower as bench support at first and in the outfield. When Lou Guisto started slowly, it was decided that Brower would platoon with him at first base. The platoon quickly gave way to Brower playing full time. He hurt his leg and it was initially feared he had cracked his shin and could miss quite a bit of playing time. He was back after nine games, but was slow to regain his stroke and his batting average fell to .229 by the Fourth of July. An eight-game hitting streak followed closely by a 13-game streak put him on the right track. Besides his 6-for-6 performance mentioned earlier, he had a two-homer, five-RBI game against the Yankees on August 4. He closed out the year batting .285 with 16 home runs, one fewer than Tris Speaker. Offensively Brower had a fine season, but in the field he committed 13 errors and had average range at best.

The Indians brought back George Burns to play first base in 1924 and Brower realized that he was at a crossroads in his career. He went to Hot Springs, Arkansas, three weeks before spring training. He was in fine physical condition when camp opened and he wowed sportswriter Henry P. Edwards, who proclaimed, “his throws come from right field like a shot … he is also batting sensationally … showing plenty of speed upon the bases.”9 However, Brower was unable to convince manager Speaker that he was the best right fielder. Homer Summa won that job despite having less power than Brower.

Brower was reduced to pinch-hitting and an occasional start, but Speaker used him in relief on four occasions, all of them losses for the Indians. Brower’s pitching was excellent as he threw 8 2/3 innings and surrendered only one earned run. Burns missed a ten-game stretch in August and September, giving Brower his only real action. He made the most of the opportunity by going 16-for-38 and adding two homers and 13 RBIs. On September 2, with George Uhle on the mound, he recorded a 20-putout game at first base. Even with that near-record, his range factor for the year was 7.85, compared to Burns’ 10.53. After the season, the Indians sold him to San Francisco in the Pacific Coast League for $7,500.

Brower spent two seasons on the coast and the results were wildly different. In 1925, he batted .362 and launched 36 home runs. Gaudy numbers until you learn that teammate Paul Waner batted .401 and Tony Lazzeri hammered 60 homers for Salt Lake City. With four other regulars batting over .300 and young Smead Jolley hitting .447 in 34 games, the Seals ran away from the competition and clinched the pennant. In 1926 Brower hit .330 and had 16 homers, but the Seals fell from the top of the standings to last place.

Before reporting to the coast in 1925, Brower was wed to Marion Dudley Merrick on February 21, 1925, in Baltimore. She accompanied him to San Francisco both seasons, but was unhappy being so far from home. The couple were expecting their first child in the summer of 1927 and decided they would rather be back in the east, so Brower requested a trade. With three left-handed-batting outfielders, Seals management hoped to work a deal for a righty. In the end, Jack Dunn of the Baltimore Orioles purchased Brower for $6,000 on February 8.10

Brower got off to a powerful start with five homers in his first 13 games. Newspapers dubbed him the “Babe Ruth of the International.”11 Brower was batting .282 and battling Buffalo’s Del Bissonette for the home run title when he was suddenly packaged with little-used pitcher Cliff Jackson in a trade with Jersey City. In return, Jack Dunn received Bucky Gaudette, a young outfielder he had coveted for a couple of years. It later turned out that the deal was more of a rental arrangement and Brower returned to Baltimore for the 1928 season and Gaudette went back to Jersey City, and then on to Montreal with the transfer of the franchise.12 The Spalding’s Baseball Guide lists Brower with a .286 average and 20 home runs in 148 games for 1928.13

Brower closed out his career playing with Baltimore in 1928-29. The family had established themselves in Queen Anne’s County across the Chesapeake Bay from Baltimore. The family added Frank Jr. just as the elder Brower was ending his baseball career. Brower Sr. worked in the grain business as a purchaser and when he retired from the game he opened his own grain business, running the business for about 25 years before selling. The new owner had the misfortune of watching the grain silo burn to the ground shortly thereafter. As for baseball, Brower managed and sponsored a semi-pro team for two seasons (1930-31).

His otherwise peaceful life was disrupted in late February 1933, when a shooting had taken place and the culprit was on the run in Queen’s Anne County. Brower joined the posse, which was later augmented with members of the National Guard. While tracking down the suspect, Brower stumbled upon his hiding place. The fugitive fired and killed Brower’s bird dog and wounded Brower in the shoulder and neck.14He recovered from the wounds and lived out his life happily. The culprit, Harry Branch, was captured by the National Guard and sentenced to four years in prison.

Baseball fans and scribes have always enjoyed creating all-time teams. Whenever talk of a Maryland Eastern Shore team came up, Brower would be included in the discussion. When sports editor Ed Nichols of the Salisbury, Maryland Daily Times discussed the group in 1945, he noted that there wasn’t really anyone for catcher. But that did not stop him from naming Jimmie Foxx, Home Run Baker, and Brower to his all-time lineup.15

Brower Sr. was hospitalized at Johns Hopkins Hospital with emphysema on November 19, 1960. He passed away from heart failure on November 21. He was buried in nearby Sudersville, Maryland, the birthplace of Jimmie Foxx.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Joel Barnhart and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Notes

1 Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 8, 1923: 14.

2 Correspondence from Ann Baxter Turner to Stan Isle, Sr. Editor of The Sporting News, January 10, 1989. Letter is contained in the HOF file for Frank Brower.

3 Scott Ostler, “A Name Game, Just in the Nick of Time,” Los Angeles Times, July 11, 1988: 43.

4 Correspondence from Frank Brower Jr. to the Baseball Hall of Fame, April 18, 1989; also, Ann Turner’s letter. Both contained in Brower’s HOF file.

5 “First Game of League was Something Awful: Better Game Promised,” The Miami News, July 25, 1913: 8.

6 “Key West Evens up the Score with Miami,” The Miami News, August 27, 1913: 10.

7 The Reach Official American League Baseball Guide, (Philadelphia: A.J. Reach Company, 1915,) 228,231.

8 Reach Guide, 1918, 134.

9 Henry P. Edwards, “Down the Sports Trail,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 25, 1924: 18.

10 Ed. R. Hughes, “Frank Brower Sold to Baltimore,” San Francisco Chronicle, February 9, 1926: 25.

11 “Hustlers and Orioles Divide League Honors,” Jersey City Journal, April 30, 1927: 14.

12 “Both “Bucky” and “Chick” Included in Montreal Sale Before Deals with Orioles,” Jersey City Journal, October 19, 1927: 19.

13 Spalding’s Official Baseball Guide, 1928, (New York: American Sports Publishing, Inc.), 175.

14 “Capture Follows Wounding of Trio,” Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), March 1, 1933: 12. Also Baltimore Sun, March 1, 1933: 1.

15 Ed Nichols, “Shore Sports,” Daily Times, June 18, 1945: 8.

Full Name

Frank Willard Brower

Born

March 26, 1893 at Cartharpin, VA (USA)

Died

November 20, 1960 at Baltimore, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.