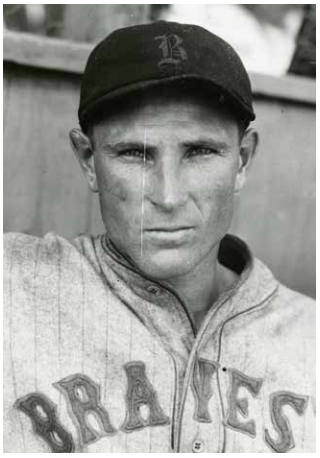

Ed Brandt

For the four years from 1931 through 1934 Edward Arthur Brandt, largely forgotten today, was one of the top left-handers in the National League. Toiling for the mediocre Boston Braves, Dutch, as he was called by his teammates, reeled off victory totals of 18, 16, 18, and 16 and was a big reason why the Braves were at or above .500 in three of those seasons, cracking the first division in 1933 and 1934. The 6-foot-1, 190-pound Brandt was anything but an overnight success and in fact was something of a reluctant big leaguer. As a youngster coming up, he suffered from an inferiority complex and homesickness that led him to jump his minor-league club on more than one occasion and head back to his comfortable surroundings of Spokane, Washington. But with the help of people like Bill McKechnie, Brandt persevered and pitched in the big leagues for 11 years.

For the four years from 1931 through 1934 Edward Arthur Brandt, largely forgotten today, was one of the top left-handers in the National League. Toiling for the mediocre Boston Braves, Dutch, as he was called by his teammates, reeled off victory totals of 18, 16, 18, and 16 and was a big reason why the Braves were at or above .500 in three of those seasons, cracking the first division in 1933 and 1934. The 6-foot-1, 190-pound Brandt was anything but an overnight success and in fact was something of a reluctant big leaguer. As a youngster coming up, he suffered from an inferiority complex and homesickness that led him to jump his minor-league club on more than one occasion and head back to his comfortable surroundings of Spokane, Washington. But with the help of people like Bill McKechnie, Brandt persevered and pitched in the big leagues for 11 years.

Brandt was born on February 17, 1905, in Spokane, one of eight children. His parents were August Brandt, born in Illinois with his occupation listed as a tinner, and the former Magdelena “Maggie” Heintz, who was born in Germany. Young Ed took to baseball at an early age and pitched his Grant Grammar School team to three school championships. He graduated to Lewis and Clark High School and continued his spectacular success, three times striking out 21 batters in a game. He quit school, however, when he got an offer to pitch for the Willys-Overland team in the Spokane City League. To support himself when he wasn’t pitching, Brandt got a job in a sawmill, but quit after a friend got his hand tangled up in a saw and lost a finger, concluding that there must be a better job for an aspiring pitcher.1

Brandt’s success pitching for Willys-Overland led to an offer from the Seattle Indians of the Pacific Coast League in the fall of 1922, when he was just 17 years old. He reported to spring training with the Indians, who trained in San Jose, California, in 1923. He soon became homesick and convinced he couldn’t compete at that level, jumped the club, and returned home to Spokane. But Seattle persisted and persuaded Brandt to report to the Aberdeen Grays of the Class-D South Dakota League to gain some confidence. After a couple of good outings there, he again became plagued with self-doubt and headed home again to Spokane, shortly before the league folded on July 17.2

Brandt later said, “I knew I would win ballgames in the semipro league, but I also knew I would be a failure in Organized Baseball.”3

He managed four appearances for Seattle in 1924 before returning home and pitching exceptionally well in the Spokane City League. Brandt remained much more comfortable pitching at the semipro level and toiled for town teams in Tonasket, Washington, and Wallace, Idaho, while making five appearances for Seattle in 1925. A Braves scout saw him in Wallace and wanted to sign him but he was under contract to Seattle and apparently failed to meet the Braves team in Chicago as promised, so Boston passed on him. In 1925, while pitching semipro ball for Baker, Oregon, he unknowingly pitched a game against a team that included Chick Gandil, one of the banned Black Sox from the 1919 World Series. Although Gandil was playing under an assumed name, Brandt found himself on Organized Baseball’s ineligible list.4

Seattle managed to get Brandt reinstated in 1926 and he appeared in four games for the Indians, going 2-0 with a 3.43 earned-run average in 21 innings. The following year, at age 22, he began to show his potential, winning 19 games against 11 losses with a 3.97 ERA in 261 innings for a third-place Seattle club. Late in the year, the Boston Braves purchased his contract for $20,000, but Brandt balked, demanding part of the purchase price. When he didn’t get it, he again jumped the club and went home to Spokane.

With no other recourse, Brandt reported to the Braves for 1928 and stuck with the club out of spring training.5 He made his major-league debut on April 15, starting the third game of the year against the Brooklyn Robins at Ebbets Field. He pitched an eight-inning complete game, losing a pitcher’s duel to Watty Clark by a 3-2 score. Brandt was about two months past his 23rd birthday. He won his first big-league game four days later on April 19 against the Giants in the Polo Grounds, relieving Joe Genewich to start the fourth inning with the Braves trailing 5-2. Boston came back to tie it, 8-8, in the ninth and won it with a run in the 10th inning to give Brandt the win. He pitched seven relief innings in all, allowing three runs on four hits.6

That performance earned Brandt a start a week later and he did not disappoint, hurling a masterful two-hit shutout against the Robins to win 4-0. As with many young left-handers, his control was not his strong suit. He walked five while striking out only one.7 After a rough outing against the Giants on April 29, Brandt pitched all 11 innings of a 5-4 extra-inning win against the Pirates in Forbes Field to bring his record to 3-2. After some indifferent starts, he again righted himself with two consecutive complete game victories in late May, 3-1 over the Phillies and 4-1 over Brooklyn, to bring his record to 5-5. He threw another complete game on June 8 to beat the Pirates 9-5 and go 6-5 with an earned-run average of 3.61.8

Brandt, however, then ran into tough sledding and lost six decisions in a row to drop his record to 6-11 and raise his earned-run average to almost 5.00. A complete-game 3-1 win against the Cubs on July 25 broke the skid, but then Brandt lost six of seven to fall to 8-17. It didn’t get any better. After a 9-2 complete-game win over Brooklyn on September 5 in which he scattered 13 hits, he lost his final four starts to fall to 9-21 for his rookie campaign. His 20th loss occurred on September 21 against the Cincinnati Reds by the score of 3-2. Brandt’s final earned-run average in 1928 was 5.07 in 225⅓ innings. He completed 12 out of 32 starts and relieved six times for 38 total appearances.

The Braves as a team managed only 50 wins against 103 losses to finish in seventh place, 44½ games out of first. Star second baseman Rogers Hornsby, who batted .387 to lead the league, had taken over as manager of the club in mid-May from Jack Slattery.9 Under Hornsby’s tutelage the team went 39-83. Hornsby disliked pitchers and was notoriously tough on them throughout his career; thus, one can surmise that the sensitive Brandt did not exactly flourish under the Rajah. In fact, Brandt was 4-16 after Hornsby became manager.

Braves owner Emil Fuchs decided to manage the team himself in 1929 and while the team won six more games than in 1928, it sank to the basement, 43 games behind the pennant-winning Cubs. Fuchs used Brandt more sparingly, due in part to Brandt’s missing almost the month of May with an injury and to his indifferent success. For the year he won 8 while losing 13, but his earned-run average rose to an unsightly 5.53 in 167⅔ innings. Still, he managed to complete 13 of his 21 starts.

Fuchs brought in future Hall of Famer Bill McKechnie to manage the club in 1930. McKechnie had a great reputation for his ability to handle pitchers, but had no early success in turning Brandt around. While the club improved to 70 wins and finished in sixth place, 22 games out of the pennant, Brandt suffered with a sore arm for much of the season and scuffled to a 4-11 record. His earned-run average (5.01) was not much improved. McKechnie used Brandt primarily as a long man out of the bullpen, but he did start 13 games, completing four.

After his first three big-league campaigns, the 25-year-old Brandt’s record stood at 21 wins against 45 losses. He was regarded “as a mystery man … [who] seemed to have everything a pitcher needed to win except confidence.”10

At some point, probably during spring training in 1931, McKecknie had a conversation with Brandt in which he asked the lefty, also known as Big Ed for his tall frame, what he liked to do in the winter. Brandt said he liked to hunt, to which McKechnie said, “Then you’d better make up your mind that you’re a major-league pitcher and not just a semipro star. If you don’t, you’ll be scratching the year ‘round on a job in a sawmill or a tin shop. Get me?”11

Brandt had undergone surgery for a chronic sinus condition over the winter, so whether it was McKechnie’s admonition or better health or both, he started the 1931 season like a house afire, winning his first eight starts, all complete-game victories. Although he cooled off a little once the dog days of summer arrived, Brandt still finished the season with 18 wins and 11 losses for a team that won only 64 games and finished in seventh place, 37 games out of the lead. His 2.92 earned-run average was third lowest in the league and his 23 complete games were second-most. He topped off his career year by being named to Babe Ruth’s mythical All-American baseball team12 and even finished 10th in National League MVP voting.

Under McKechnie, the Braves improved to .500 and fifth place in 1932 with a 77-77 record. Brandt again was the workhorse of the staff, leading the team in wins while also finishing at .500 with a 16-16 record in 254 innings. His earned-run average jumped by a run to 3.97 and he gave up more hits, 271, than innings pitched. He completed 19 of 31 starts and tossed two shutouts.

Brandt returned to his 1931 form in 1933, again posting 18 wins against 14 losses as the Braves improved to an 83-71 record to finish in the first division, only nine games behind the pennant-winning New York Giants.13 He could again claim to be, along with Carl Hubbell, one of the top two left-handers in the National League. His 2.60 earned-run average was fourth lowest in the league while his 23 complete games were the third most and his 288 innings were fourth highest.

Brandt pitched in tough luck early in 1933 and his 5-3 loss to the Pirates on June 18 dropped his record to 4-8, even though his earned-run average stood at 2.77. But from there he went 14-6, benefiting from better run support as he continued to pitch well. During one stretch Brandt won six decisions in a row, including a four-hit shutout against the Cincinnati Reds on July 2. He finished the season by winning four of five starts, including another four-hit shutout of the Reds on September 19.

Brandt was one of the best hitting pitchers in the National League during his career and in 1933 had his best year at the plate, batting .309 with 30 hits in 97 official at-bats. He was a good-enough hitter to be used as a pinch-hitter several times during his career, which ended with his batting average at a more than respectable .236.

In 1934 Brandt had another solid year, finishing at 16-14 for a Braves team that again finished in fourth place, with a 78-73 record. He threw 20 complete games among his 28 starts, fifth most in the league, and finished with a respectable 3.53 earned-run average in 255 innings. He threw a two-hit shutout against the Cubs in May, a three-hit shutout of the Pirates in July, and whitewashed the Giants in August on another two-hitter.

The Braves’ 1935 season began with a lot of hoopla as the team signed the 40-year-old Babe Ruth. Brandt pitched the season opener on April 16 and defeated Giants ace Carl Hubbell, 4-2, as the Babe smashed a home run and a double and made a great running catch in left field.14 But Ruth was at end of the line and on June 2 announced his retirement, as the wheels were coming off the bus both for the Braves and for Brandt.15 The team fell off the cliff to a 38-115 record, finishing in the basement, 61½ games out of the lead and 26½ games out of seventh place. The team lost 15 in a row on the road in July and then went 2-28 from mid-August to mid-September.16

Brandt didn’t help rescue the Braves as his earned-run average rose to 5.00 in 174⅔ innings and he won only five of 24 decisions. On April 27 he beat the Dodgers 4-2 to bring his record to 2-1 for the young season. He then lost seven in a row. On June 30 Brandt defeated the Phillies 9-3 in a complete-game 12-hitter to bring his record to 5-8. It was his last win of the season as, plagued by a sore arm,17 he lost 11 consecutive decisions to finish the year 5-19.18

With nothing to lose, the Braves cleaned house after their disastrous ’35 campaign and on December 12 dealt Brandt and utilityman Randy Moore to the Brooklyn Dodgers for second baseman Tony Cuccinello, catcher Al Lopez, and pitchers Ray Benge and Bobby Reis.19 The Dodgers were entering their third season with Casey Stengel at the helm and had finished 29½ games off the lead in fifth place in 1935. The trade didn’t help much as the club slipped to seventh in 1936, 20 games under .500.

Brandt was in effect the Dodgers’ number-three starter, behind Van Lingle Mungo and Fred Frankhouse, who had come over from the Braves in a separate deal. Brandt started the year slowly and after a 5-3 loss to the Cubs on July 21, saw his record fall to 3-10. But with better run support, he won eight of his final 11 decisions to finish with an 11-13 record. He threw 12 complete games in 29 starts and ended with a respectable 3.50 earned-run average in 234 innings.

Brandt showed his moxie and impressed at least one sportswriter when he was felled by a first-inning line drive struck by Johnny Moore of the Phillies in a meaningless game at the Baker Bowl on August 5. He staggered to his feet, and although initially wobbly, finished with eight shutout innings to win the game 7-3.20 In Brandt’s last start of the year, he pitched 12 innings against the Phillies in a no-decision that the Dodgers lost in the 13th, 4-2. One headline the next day was titled “Brandt Closes Luckless Year with Dodgers.”21

Brandt’s strong finish convinced the Pittsburgh Pirates to acquire him after the season in a trade for southpaw pitcher Ralph Birkofer and infielder Cookie Lavagetto. The Pirates had finished in fourth place the previous two seasons under manager Pie Traynor and were looking for pitching help to bolster a lineup that had hit a robust .286 in 1936 to tie for the league lead. It was a chance for Brandt to pitch for a contender as well as for a club that could provide run support.

Brandt won his first three starts as the Pirates got off to a fast start in 1937, winning 11 of their first 14 games. But plagued by lack of run support, his old bugaboo, and a sore arm, he lost his next five decisions to fall to 3-5 as the Pirates settled into third place. Brandt, who was known to drink and carouse a bit, also managed to get cross-ways with strait-laced manager Traynor. As a result, there was speculation that Traynor did not use Brandt as much as he might have during Brandt’s tenure with the club.22

Brandt continued to be inconsistent in ’37 but pitched a sparkling two-hit shutout against his old team, now called the Boston Bees, on July 30 in a game the Pirates won 1-0 with a run in the bottom of the ninth.23 He similarly defeated the Reds 1-0 on September 9 in a game the Pirates also won in the bottom of the ninth on an Arky Vaughn triple and a single by Bill Brubaker.

For the season, Brandt won 11 and lost 10 in 176 innings with a solid 3.11 earned-run average. He started 25 games, completed seven, and appeared eight times in relief as the Pirates finished in third place with an 86-68 record, 10 games off the pace.

After the season, it was revealed that Brandt had secretly gotten married during the season on August 5 in Wheeling, West Virginia. It was reported that the newly married couple was spending the offseason on Brandt’s ranch near Libby, Montana.24

The 33-year-old Brandt returned to the Pirates for the 1938 season but was plagued by arm trouble early in the year and missed three weeks in late June and early July. He was used as a spot starter, with 13 starts, and in relief, with 11 appearances. Brandt was still capable of throwing a gem and shut out the Phillies 8-0 on July 19 for his second win of the year. But for the year he was inconsistent and finished 5-4 with a 3.46 earned-run average in only 96 innings for a Pirates team that was in the pennant race all year and finished in second place, only two games behind the Cubs, their hearts broken by Gabby Hartnett’s famous homer in the gloamin’.

Brandt reported to spring training with the Pirates in 1939 in San Bernardino, California. However, he was abruptly given his unconditional release by Traynor on March 23 for “breaking training rules.” According to Traynor, Brandt didn’t arrive at the team hotel the night before “until a little before breakfast time.”25 Five days later Brandt signed with the Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League.26 He began the season with the Stars but again encountered arm problems. After going 2-3 in six appearances, he was again released, effectively ending his professional baseball career.27

After baseball, Brandt returned to Spokane and then for a time ran a dude ranch and hunting lodge that he had purchased in Montana. He spent about six months in the Army in 1942 and 1943 and was a private in the 41st Armored Regiment stationed at Camp Polk, Louisiana, where he was listed as a physical director.28 He was apparently discharged because of his age and again returned to Spokane to work in the local war industry. He subsequently purchased a tavern in nearby Clayton but continued to live in Spokane.29 He was granted a divorce from his wife in August 1944.30

Shortly before midnight on the evening of November 2, 1944, Brandt and his fiancée were involved in a minor traffic accident as they prepared to return to Clayton from Spokane. As Brandt talked on the street to the driver of the other car, he was struck and fatally injured by another car that was traveling about 40 miles per hour.31 He was just 39 years old.

Ed Brandt’s lifetime major-league record was 121 wins against 146 losses with a 3.86 earned-run average. Although he finished 25 games under .500, it is important to remember that he toiled for second-division teams for the bulk of his career and was uniformly considered a hard-luck pitcher during his playing days.32 From 1931 through 1934, he was considered one of the elite left-handers in the National League, finishing among the league leaders in innings pitched, complete games, and shutouts. During those years, he averaged 17 wins a campaign and put together a 68-55 record for Braves teams that finished no better than fourth place. Not bad for a reluctant major leaguer who for many years thought he could never succeed in Organized Baseball.

This biography is included in “20-Game Losers” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Emmet R. Nowlin.

Sources

The author would like to thank Greg Ivy for his genealogical research help for this biography.

Notes

1 Harry T. Brundidge, “Ed Brandt Won Belated Success After Prolonged Battle,” The Sporting News, November, 19, 1931: 7.

2 Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds., The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 2d ed. 1997); Brundidge: 7.

3 John E. Spalding, Pacific Coast League Stars, Volume II (Manhattan, Kansas: Ag Press, 1997), 46.

4 Brundidge: 7; Tommy Holmes, “Ex-Brave Signs With Flatbush Club,” unidentified clipping dated January 24, 1936, from the Ed Brandt clippings file, National Baseball Library.

5 Brundidge: 7.

6 The Giants’ lineup featured Hall of Famers Bill Terry, Edd Roush, Freddie Lindstrom, and Travis Jackson as well as Lefty O’Doul, who many believe should be in the Hall of Fame.

7 He had also walked five in his first appearance, but also struck out five.

8 Two of the runs scored by the Pirates were unearned.

9 The 1928 Braves not only had Hornsby at second, but had future Hall of Famer George Sisler playing first base.

10 “And then suddenly the big left-hander was off to the races,” Holmes.

11 Brundidge: 7.

12 Harold “Speed” Johnson, Who’s Who in Major League Baseball (Chicago: Buxton Publishing Co., 1933), 89.

13 Ben Cantwell had his career year in 1933 and could lay claim as the ace of the Braves staff. He went 20-10 with a 2.62 earned-run average in 255 innings. By 1935 Cantwell had slipped to an unsightly 4-25 record. Cantwell’s lifetime record was 76-108, although his career earned- run average was a respectable 3.91.

14 Harold Kaese, The Boston Braves – An Informal History (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1948), 231.

15 Al Hirshberg, The Braves – The Pick and the Shovel (Boston: Waverly House, 1948), 49-62; Mitchell Conrad Stinson, Deacon Bill McKechnie – A Baseball Biography (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2012), 154-58.

16 Gary Caruso, The Braves Encyclopedia (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1995), 56-57; Jonathan Weeks, Cellar Dwellers – The Worst Teams in Baseball History (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 2012), 91-102.

17 Holmes.

18 He did pitch in some tough luck, losing two games by 3-2 scores, one by a 2-1 count, and one 1-0 game.

19 While the trade seemed to favor the Braves, it largely involved players who seemed to be on the downside of their careers. Dan Daniel, “Brooklyn Given Brandt and Moore in Big Deal,” New York World-Telegram, December 13, 1935.

20 The Old Scout, “Pirates Aided by Acquisition of Ed Brandt,” unidentified clipping dated December 7, 1936, from the Ed Brandt clippings file, National Baseball Library.

21 Edward T. Murphy, “Brandt Closes Luckless Year with Dodgers,” unidentified clipping dated September 25, 1936, from the Ed Brandt clippings file, National Baseball Library. Hugh Mulcahy pitched all 13 innings for the Phillies. He earned his first major-league victory when Chile Gomez hit a two-run single in the top of the 13th and Mulcahy followed with a scoreless bottom half of the inning.

22 James Forr and David Proctor, Pie Traynor – A Baseball Biography (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2010), 148, 169.

23 Al Todd doubled to lead off the ninth, moved to third on a bunt hit by Pep Young, and scored on a fly ball by Red Lucas to end the game.

24 Unidentified clipping dated October 7, 1937, from the Ed Brandt clippings file, National Baseball Library.

25 Brandt was released even though it left the Pirates with only one left-handed pitcher, rookie Ken Heintzelman. “Pirates Release Brandt, Veteran,” unidentified clipping dated March 23, 1939, from the Ed Brandt clippings file, National Baseball Library. Traynor reportedly sat in the hotel lobby until 3 A.M. waiting for Brandt and teammate Russ Bauers to come in for the evening before giving up and going to bed. Forr and Proctor, 173-74.

26 Unidentified clipping dated March 28, 1939, from the Ed Brandt clippings file, National Baseball Library.

27 “Hollywood Club Releases Ed Brandt,” unidentified clipping dated May 3, 1939, from the Ed Brandt clippings file, National Baseball Library.

28 Unidentified clipping dated January 21, 1943, from the Ed Brandt clippings file, National Baseball Library.

29 “Crash Fatal to ‘Lefty’ Brandt,” Spokane Spokesman-Review, November 3, 1944: 15.

30 Unidentified clipping dated August 31, 1944, from the Ed Brandt clippings file, National Baseball Library.

31 Brandt was struck by a car driven by First Lieutenant Louis Sanchez, who was convalescing at the Fort Wright Hospital from battle fatigue after more than 50 missions over Germany as a bombardier. He had won the Air Medal and Distinguished Flying Cross and may have been suffering from what we would now call post traumatic stress syndrome. On the night of the accident Sanchez was being followed by a patrol car because of his speeding and erratic driving. No alcohol was involved, however. “Question Raised in Brandt Death,” Spokane Spokesman-Review, November 3, 1944: 14.

32 Murphy, “Brandt Closes Luckless Year with Dodgers”; The Old Scout, “Pirates Aided by Acquisition of Ed Brandt” (“For eight years the husky left-hander has been tossing ’em in for light scoring teams.”); Letter to the Editor of The Sporting News from J. Roberson dated June 1, 1933, from the Ed Brandt clippings file, National Baseball Library (Ed Brandt is “the greatest pitcher in the National League” and “the champion hard luck pitcher in the game today,” and would win 25 games with a better-hitting team).

Full Name

Edward Arthur Brandt

Born

February 17, 1905 at Spokane, WA (USA)

Died

November 2, 1944 at Spokane, WA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.