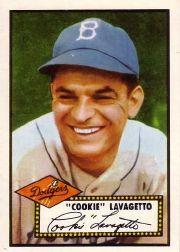

Cookie Lavagetto

Harry Arthur “Cookie” Lavagetto is best known for one swing of the bat against Bill Bevens of the New York Yankees on an October day in 1947. But his baseball career, as a player and manager, was much more than that. The six-feet, 170-pound Lavagetto played professional baseball for ten seasons over a fourteen-year span, losing four seasons to service in the navy during World War II. Lavagetto, a four-time All-Star at third base, had a career batting average of .269 and played in two World Series as a member of the Brooklyn Dodgers, in 1941 and 1947. He was the last manager of the American League Washington Senators, from 1957 through 1960, and the first manager of the Minnesota Twins when the Senators relocated there for the 1961 season.

Harry Arthur “Cookie” Lavagetto is best known for one swing of the bat against Bill Bevens of the New York Yankees on an October day in 1947. But his baseball career, as a player and manager, was much more than that. The six-feet, 170-pound Lavagetto played professional baseball for ten seasons over a fourteen-year span, losing four seasons to service in the navy during World War II. Lavagetto, a four-time All-Star at third base, had a career batting average of .269 and played in two World Series as a member of the Brooklyn Dodgers, in 1941 and 1947. He was the last manager of the American League Washington Senators, from 1957 through 1960, and the first manager of the Minnesota Twins when the Senators relocated there for the 1961 season.

Lavagetto’s parents were Luigi S. and Adelaide (Lavagett) Lavagetto, both born in Italy in the mid-1870s. Luigi arrived in the United States in 1901; Adelaide arrived in 1906. Harry, the youngest of four boys, was born on December 1, 1912, in Oakland, California and christened Enrico Atillio Lavagetto.1 His name was “changed” twice. After his Catholic Church confirmation, the middle name Attilio became Arturo. And on his first day of school, he was told by his teacher that in English, Enrico was either Henry or Harry. He decided on Harry, and from that day forward, he was known as Harry Arturo Lavagetto. It was during these early days at school in Oakland, that Harry met Mary Poggi. It was a long courtship; they finally married in 1945. “Our families used to go mushroom-hunting together in the hills above Oakland,” Lavagetto recalled.2

Playing major-league baseball had always been young Harry’s dream. Shortly after graduating from Oakland Technical High School, he had a tryout with San Francisco of the Pacific Coast League.3 Living just across the bay, Lavagetto was eager for the chance to play professional baseball so close to home. But he flopped during the tryout and assumed his goal of playing in the big leagues was over. Moreover, his father had been pressuring him to start earning a living.

A week after the tryout, Lavagetto heard of a game that was being put together between some big leaguers on the West Coast who were about to leave for spring training and an All -Star semipro team. Proceeds of the game were to go toward an insurance fund to pay for hospital bills for semipro players who got injured.

Lavagetto was picked to play for the semipro team and was slated to come into the game after the fifth inning with other substitutes. When he came to bat, his team was down two runs and the bases were loaded with two outs. On the mound was Al “Pudgy” Gould, who had played two seasons (1916-17) with the Cleveland Indians and had a long career in the Pacific Coast League. Harry hit a Gould pitch high off the right-field wall for a bases-clearing double, securing the lead and eventually the win for the semipros. After the game, he received nine offers to play professionally.

Lavagetto called that hit his greatest moment in baseball. “Everything stemmed from that one shot I hit,” he told Washington sportswriter Bob Addie. “There would have been no big-league career, no chance to spoil Bevens’s no-hitter. One swing changed the whole course of my life because I was almost to the point, after being released by San Francisco, where I was going to give up the idea of ever playing big-league ball.”4 Lavagetto signed with Cookie DeVincenzi, owner of the Pacific Coast League’s Oakland Oaks. Harry became known as “Cookie’s boy” and, eventually, just plain Cookie.5

Lavagetto began his professional career as a second baseman with the Oaks in 1933, batting .312 in 152 games.6 Pittsburgh Pirates scout Bill Hinchman signed him, and he spent three seasons (1934-36) with Pittsburgh, moving between second base and third base. In 1934, his rookie season, Lavagetto played in eighty-seven games, all at second base, but his playing time decreased sharply in each of the next two years. Lavagetto’s combined batting average for his three seasons in Pittsburgh was .249.7

On December 4, 1936, the Pirates traded Lavagetto and pitcher Ralph Birkofer to the Brooklyn Dodgers for pitcher Ed Brandt.8 Lavagetto played in 100 games at second base in his first year with the Dodgers, but for the rest of his major-league career, he was primarily a third baseman. In Cookie’s first season with Brooklyn, he batted .282 with seventy runs batted in. The next season, 1938, Lavagetto became an All-Star for the first time, and in 1939 had the best season of his career, batting .300 with eighty-seven RBIs.

Lavagetto had the reputation of being somewhat of an oddball during his playing days. “Cookie was a character,” said a sportswriter who covered the Dodgers then. “He walked funny and always needed a shave,” the writer told Sports Illustrated. “His shirt would be hanging out of his pants, and he wore his hat at a weird angle. Cookie would just sit there, not realizing he looked any different than the next guy.” Lavagetto was well-liked in the clubhouse and often enjoyed making his teammates laugh. “Oh, I used to know it,” Lavagetto told Sports Illustrated. “I used to enjoy wearing one sock up, the other down. I don’t know why exactly. I just enjoyed it.”9

Lavagetto was chosen for the All-Star Game in every season from 1938 through 1941. After not playing in the 1938 and ’39 games, he was the National League’s starting third baseman in 1940 and a pinch-hitter in 1941. The Dodgers won the National League pennant in 1941 but lost to the New York Yankees in the World Series. In January 1942, with the United States at war, Cookie applied for enlistment in the Navy. On February 17 in San Francisco, he was sworn in as an aviation machinist’s mate first class, and shortly afterward reported for duty at the Alameda (California) Naval Air Station.

“We don’t think enough credit has been given to Cookie Lavagetto for his enlistment in naval aviation,” wrote Bob Considine on February 3, 1942, in his weekly column “On The Line.” “After all, most of the athletes who have gotten wild applause of late for their patriotism were drafted into the services. Lavagetto, several times chosen as the best third baseman in the National League, and with five or six prosperous years of baseball before him, was in Class 3-A and might have remained there even if we were invaded as deep as Akron. He enlisted the moment his brother, whom he had been supporting (along with a number of others), got a defense job. He felt morally called upon to give to the government his ability to fly a plane. Anyway, my lid’s off to a good, game guy who, with a minimum of fanfare and under no compulsion, is doing his bit.”

Considine’s mention of flying was a reference to the fact that in 1938, Harry and teammate Dolph Camilli decided to take flying lessons. After they got their pilot’s licenses, the Dodgers’ chief executive, Larry MacPhail heard about it and, irate, fined the pair $500 apiece for activities detrimental to the ballclub.

While with the Navy in California, Cookie played baseball whenever he could. He competed against the same Oakland Oaks team for whom he had once played. Lavagetto played for the Navy team in an Army-Navy All-Star game on July 5, 1943, at Seals Stadium in San Francisco. While stationed at the Livermore (California) Naval Air Station in ‘43, he played for a Navy team that won sixty of its seventy games.10

Soon after he married Mary Poggi, on April 10, 1945, Cookie was reassigned to Hawaii, where he managed a Navy team that included Stan Musial. In 1946, with World War II over, Lavagetto returned to the Dodgers at the age of thirty-three. He had missed four seasons, and his skills had eroded. “I was washed up,” he told Sports Illustrated. He played in only eighty-eight games in 1946 and forty-one in 1947.11 Nineteen forty-seven was his last big-league season, and Cookie went out with a flourish.

The Dodgers won the pennant in ‘47 and faced the New York Yankees in the World Series. It was during that Series that Lavagetto solidified himself in baseball history and lore. On October 3, with the Yankees leading the Series two games to one, Bill Bevens was on the mound for the Yankees at Ebbets Field. In the bottom of the ninth inning, the Yankees led, 2–1. Although he had walked eight Dodgers, Bevens was just three outs away from throwing the first World Series no-hitter. Bruce Edwards, the Dodgers’ first batter, flied out. Carl Furillo worked Bevens for the pitcher’s ninth walk. Spider Jorgensen fouled out. There was one more out to go.

Dodgers manager Burt Shotton sent Al Gionfriddo in to run for Furillo. Gionfriddo stole second, while Bevens was pitching carefully to Pete Reiser. With a 3-and-1 count on him, Reiser was given an intentional walk, Bevens’s tenth walk of the game. Eddie Miksis pinch-ran for Reiser, and Shotton sent the right-handed hitting Lavagetto up to pinch-hit for the right-handed hitting Eddie Stanky.

Lavagetto had always been a good clutch hitter and there was no better situation than this. Bevens’s second pitch to Cookie was high and outside. Lavagetto smashed the ball over right fielder Tommy Henrich’s head and off the wall. Gionfriddo scored from second. Henrich threw the ball home, but the relay arrived at the plate just as the speedy Eddie Miksis slid in with the winning run. Lavagetto’s smash robbed Bevens of a no-hitter and a victory, and the Series was tied. Lavagetto was mobbed in the center of the field by his teammates and needed a police escort to get to the dugout. Bevens later told Lavagetto, “We were told to throw you high and outside.” Harry replied, “That’s just where I like them.”

The hit was Lavagetto’s last in the major leagues. He was released by the Dodgers on May 3, 1948. After his release, Lavagetto returned to the Oakland Oaks, where he played through 1950 under managers Casey Stengel and Charlie Dressen. Dressen was hired as the Dodgers manager in 1951, whereupon Lavagetto quit playing and signed on with Brooklyn as a coach. When Dressen was refused a two-year contract after the 1953 season, Cookie sent owner Walter O’Malley a telegram that read: “Please accept resignation.” The loyalty Lavagetto had toward Dressen was strong, and he followed Dressen back to Oakland as a coach.

In 1955 Dressen was named manager of the Washington Senators and brought Lavagetto with him. After two disappointing seasons, Dressen was fired early in the 1957 season. The managing job was offered to Cookie but, ever loyal to Dressen, he refused it. Only after Dressen begged him to accept did he take the job, his first as a manager. Lavagetto never thought of himself as anything but a coach and he had a tough time at first adjusting to the position. Cookie was used to being out of the spotlight and had always deflected sportswriters’ questions to Dressen. He liked playing cards with the players and enjoyed his anonymity.

That all changed for Lavagetto when he became a manager. The life free of mental strain was gone and he was thrust into the limelight. People now wanted to hear what he had to say. On the road he was given a suite in the team’s hotel. He did not like being alone and missed having a roommate. He also did not like deciding the batting order and the pitching rotation and making decisions during games. What bothered him most was dealing with the losses of a last-place team. Eventually the constant worrying took a toll on Cookie, and he began to have trouble sleeping and eating and even broke out in hives.

After a while, Lavagetto became confident enough to run the team and realize that he could handle the job. It took time for the Senators to improve, but eventually they did. After finishing in eighth place during the first three seasons under Lavagetto, the team improved to fifth in 1960.12

Following the 1960 season, owner Calvin Griffith moved the team to Minnesota where Lavagetto became the first manager of the new Minnesota Twins. Cookie and the team were welcomed to Minnesota with open arms and Cookie was an instant celebrity. He was treated like royalty in the Twin Cities; he was given cars from local dealerships and had his own radio show before each home game. Cookie’s reaction was: “I prefer to remain in obscurity.”13

Despite the warm welcome, Lavagetto’s time as manager of the Twins lasted just fifty-nine games. With the teams’ record at 23-36, he was replaced by one of his coaches, Sam Mele. Griffith cited the team’s sluggish start and differences in opinion on player talent as his reasons for firing Lavagetto; “He wanted to get rid of just about everybody I wanted to keep,” Griffith said.14

Lavagetto took the rest of the season off and then returned to coaching with the newborn New York Mets in 1962. He remained with the Mets through 1963. In 1964 he moved closer to home after a false diagnosis of lung cancer and a related operation. He hired on that season as a coach with the San Francisco Giants and stayed with the Giants until he retired after the 1967 season.

Lavagetto died on August 10, 1990, at his home in Orinda, California. He and his wife had two sons, Michael, who became a Catholic priest, and Ernest.

Sources

Some of the biographical information came from an April 11, 2010 telephone interview Thomas Bourke did with Cookie Lavagetto’s son Ernest in Walnut Creeek,California.

Notes

1. The state of California and the 1920 U.S. census list him as Attilio H. Lavagetto.

2. http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/article/magazine/MAG1072554/index.htm

3. http://oaklandoaks.tripod.com/lavagetto.html

4. Addie, Bob, “Destiny Goes To Bat,” Baseball Digest, August 1956, p. 43-44

5. http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/article/magazine/MAG1072554/index.htm

6. http://www.baseball-reference.com/minors/player.cgi?id=lavage001har

7. http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/l/lavagco01.shtml

8. http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/l/lavagco01.shtml

9. http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/article/magazine/MAG1072554/2/index.htm

10. http://www.baseballinwartime.com/player_biographies/lavagetto_cookie.htm

11. http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/article/magazine/MAG1072554/3/index.htm

12. http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/article/magazine/MAG1072554/4/index.htm

13. http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/article/magazine/MAG1072554/1/index.htm

14. “Ermer Tabbed as Twins’ Pilot 13 Years Ago!”, Baseball Digest, March 1968, p. 56

Full Name

Harry Arthur Lavagetto

Born

December 1, 1912 at Oakland, CA (USA)

Died

August 10, 1990 at Orinda, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.