April 23, 1919: Lefty Williams, White Sox win in Kid Gleason’s managerial debut

When the Chicago White Sox took the field for Opening Day in 1919, no one knew which version of the team would come to play.1

When the Chicago White Sox took the field for Opening Day in 1919, no one knew which version of the team would come to play.1

Charles Comiskey’s club had ended the previous season in a disappointing sixth place, following the loss of stars like Eddie Collins to the Marines and Shoeless Joe Jackson to the shipyards during World War I. The war had cast a dark pall over baseball as the US government instituted a “work or fight” order that forced players to enlist in the military or take essential defense-industry jobs, and also ended the 1918 season in early September. Fearful team owners, worried that fans wouldn’t return to the game, cut the 1919 schedule by two weeks and made other cost-saving moves, including the establishment of a short-lived salary cap.

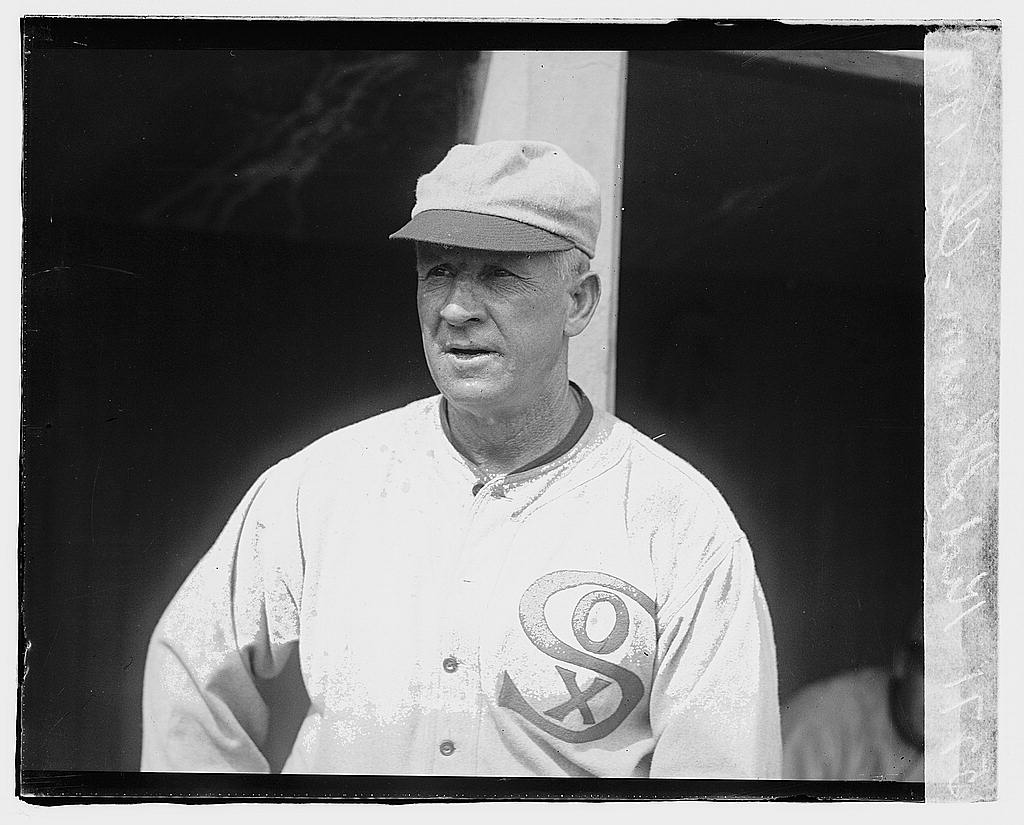

But the entire starting lineup from Chicago’s World Series-winning squad of 1917 was now back on the roster and the same nine players who were on the field for Opening Day of that championship year were penciled in for the first game in 1919. The manager who wrote out the White Sox lineup, however, was different. In an offseason move that surprised the baseball world, Comiskey fired the skipper who had led his team to a title, Pants Rowland, and replaced him with William “Kid” Gleason.

The 52-year-old Gleason had spent more than three decades in the game as a player and coach, but he had never managed in the big leagues. He took over the reins after sitting out the 1918 season in a salary dispute with Comiskey, who persuaded him to sign on as manager after promising to re-sign Collins, Jackson, and the other players who had left the team during the war.2

Gleason was well respected throughout the American League, but few experts gave his White Sox a chance to win the pennant. “Unless he has a lot of luck developing new pitchers, [Gleason] is going to have a hard time keeping his team in the first division,” wrote Irving Sanborn of the Chicago Tribune.3 Pitching depth was a major problem for Chicago, with future Hall of Famer Red Faber sidelined by injury and a lingering bout of the flu.4 Rookies Dickey Kerr and John Sullivan and the 20-year-old prospect Frank Shellenback were still unproven, so the White Sox pitching staff relied almost exclusively on ace Eddie Cicotte and young Lefty Williams to carry the load.5

Entering his fourth major-league season, Williams got the call to start on Opening Day, April 23, 1919, against the St. Louis Browns. The veteran Cicotte was held back because he superstitiously believed that the rest of his year was doomed if he pitched on Opening Day.6 It didn’t hurt that the Browns’ top hitters, George Sisler, Ken Williams, and Ray Demmitt, all batted from the left side against the southpaw Williams.

About 15,000 fans filed into Sportsman’s Park by the time the game began at 3:30 P.M. The White Sox broke out new road uniforms of “steel gray with blue trimmings and the traditional white stockings.”7 A pregame ceremony was held to honor Browns manager Jimmy Burke and fellow St. Louis natives Jack Tobin and Lefty Leifield. White Sox catcher Ray Schalk, who grew up about 50 miles north of St. Louis in Litchfield, Illinois, was also given a bouquet of flowers during the game.

Right-hander Dave Davenport took the mound for the Browns and was immediately handed a 2-0 lead when Demmitt’s line drive skipped past center fielder Happy Felsch for a two-run triple in the first inning. It was all downhill from there as the White Sox offense bombarded Browns pitchers for 13 runs and 21 hits over the next two hours.

Buck Weaver’s two-run triple and Joe Jackson’s RBI single in the third inning gave the White Sox the lead and drove Davenport from the game. Manager Burke said his pitcher’s control was “too good” — which the St. Louis Post-Dispatch translated to mean that Davenport threw everything over the middle of the plate “with regularity and certainty.”8

His replacement, Tom Rogers, fared no better, allowing four runs before recording three outs in the fourth inning. Weaver drove in two more runs with a one-out single, then Eddie Collins greeted reliever Lefty Leifield with an inside-the-park home run to center field, putting the White Sox ahead 8-3.

Chicago’s left-handed sluggers had no trouble with the Browns’ southpaw pitchers, Leifield and Ernie Koob, who allowed four runs in his two innings of work. The platoon “had about as much effect in stopping the Sox as a bartender’s wishes might have in stopping Prohibition,” one writer quipped.9

Even White Sox pitcher Lefty Williams (a right-handed batter) enjoyed some rare success at the plate, recording three hits and scoring three runs as the game reached blowout status by the final innings. Williams’s offensive highlight was a triple in the ninth inning to score Swede Risberg. Weaver brought him home with a single — his fourth hit and fifth RBI of the day. Jackson and Risberg also had three hits apiece, while Chick Gandil doubled, tripled, and scored twice.

It was an auspicious start for the White Sox — a team long known as the “Hitless Wonders” — who would go on to lead the American League in hits, runs scored, and stolen bases. Kid Gleason spent the rest of the season worrying about his pitching staff behind Williams and Cicotte, but his offensive attack was already back in championship form.

Sources

Play-by-play information was recorded in the following game recaps:

Bell, Floyd L. “Sothoron May Stop Sox in Second Game of Browns’ Series,” St. Louis Star, April 24, 1919: 19.

Sanborn, I.E. “White Sox Bombard Browns in Year’s First Battle, 13-4,” Chicago Tribune, April 24, 1919: 19.

Wray, John E. “Extra! Four Brown Pitchers Slaughtered on Hurling Hill; Nine White Sox Are Implicated,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 24, 1919: 28.

Box scores can be found at Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org:

baseball-reference.com/boxes/SLA/SLA191904230.shtml.

retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1919/B04230SLA1919.htm.

Notes

1 This problem would plague the notorious 1919 White Sox all season long … for different reasons.

2 James Crusinberry, “Kid Gleason Appointed Manager of the White Sox,” Chicago Tribune, January 1, 1919: 31. Comiskey was furious that some of his players chose to accept “unpatriotic” shipyard jobs over the military, including Jackson, Lefty Williams, and backup catcher Byrd Lynn. He threatened to blacklist them from baseball once the war ended, but relented when Gleason persuaded him to keep his championship team intact. For more on the Jackson shipyard controversy, see the author’s article, “1919 White Sox: Prologue,” at sabr.org/research/1919-white-sox-prologue-offseason-1918-19.

3 I.E. Sanborn, “Baseball Races Start on Wednesday,” Chicago Tribune, April 20, 1919: 17.

4 The influenza pandemic in 1918-19 was the deadliest disease outbreak in human history, killing more than 600,000 Americans and millions of people worldwide. John M. Barry, “How the Horrific 1918 Flu Spread Across America,” Smithsonian Magazine, November 2017, https://smithsonianmag.com/history/journal-plague-year-180965222.

5 Cicotte and Williams were up to the challenge, earning 52 of the White Sox’s 88 victories in 1919.

6 I.E. Sanborn, “Gleason’s Men All Ready for Pennant Drive,” Chicago Tribune, April 23, 1919: 19. Cicotte made only two Opening Day starts in his career, in 1910 for the Red Sox (7 IP, 9 H, 2 R in a 4-4 tie) and in 1918 for the White Sox (4⅓ IP, 11 H, 3 R in a 6-1 loss.)

7 “White Sox Notes,” Chicago Tribune, April 24, 1919: 19.

8 John E. Wray, “Extra! Four Brown Pitchers Slaughtered on Hurling Hill; Nine White Sox Are Implicated,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 24, 1919: 28.

9 Ibid.

Additional Stats

Chicago White Sox 13

St. Louis Browns 4

Sportsman’s Park

St. Louis, MO

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.